The Best Way To See America Is To Visit Every Last Minor League Ballpark

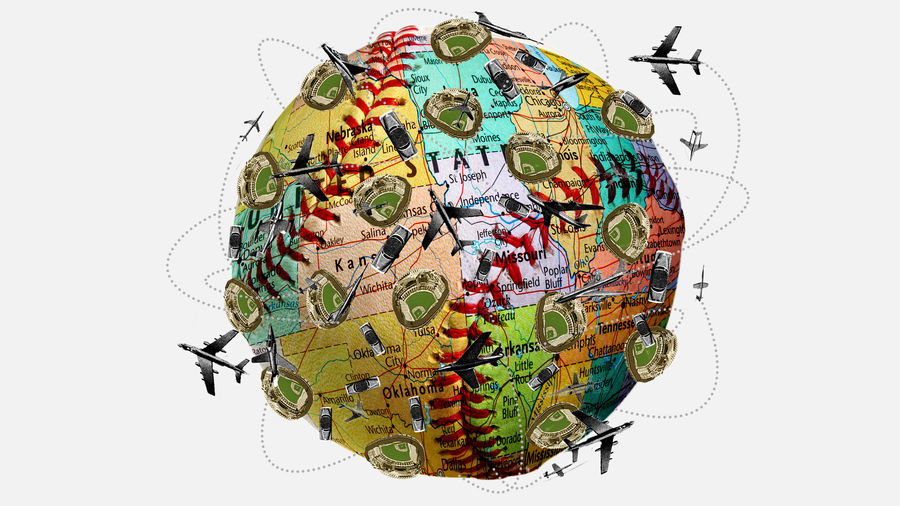

Ah but have you been to Salina in July? credits: Elena Scotti

Ah but have you been to Salina in July? credits: Elena Scotti Not long after the 2017 World Series ended in a dogpile of happy Houston Astros, Bart Wilhelm began planning his first big trip of the 2018 season. For more than half a decade, Wilhelm has been “chasing” Minor League ballparks, with the goal of attending a game in all 159 of them. Wilhelm began the 2018 season 26 ballparks shy of that goal, including a bunch in the southeastern United States. And so he mapped out a road trip that would take him from his home in Traverse City, Michigan, to ballparks in Jackson, Mississippi, and Mobile, Alabama, and Memphis and Biloxi and Birmingham, and then finally to the small city of North Augusta, South Carolina, where the Augusta GreenJackets of the South Atlantic League were just moving into a new facility. He finally reached ballpark 159 in August, when he watched the Royals’ Appalachian League affiliate play a home game at Burlington Athletic Stadium in North Carolina.

Wilhelm’s obsessive pursuit is remarkable, but not his alone. All over the country, other ballpark chasers spend their winters planning similar trips. Tempe accountant Ty Kramer consulted with his brothers and sometime-travel partners about their potential plans for 2018 at Christmas, and they settled on a trip that began in Little Rock and took them to Springdale, Arkansas, then Tulsa, and then to four other Minor League parks in Texas: Frisco, Round Rock, San Antonio, Corpus Christi. Kramer would add 17 Minor League ballparks in all in 2018, putting his total number at 141.

Spend some time browsing the Facebook groups where chasers post photos and swap travel tips — Facebook groups that, incidentally, are just about the most civil and supportive places on the internet this side of the Katmai Fat Bear Aficionado Community — and you’ll learn that there are various strains of ballpark chaser. Some set out to visit all 30 Major League parks and are happy to leave it there. Others extend the pursuit to other sports, chasing NFL, NBA, and NHL teams. Chasing Minor League ballparks, though, is an especially ambitious and logistically complicated project.

“You’re not just going to wake up one day and think, ‘Oh, you know what? I’ve been to all of the parks,’” says Joe Mock, the founder of BaseballParks.com. He first joined the completist club in 2014 and has stayed current by visiting every park that has opened since. “It’s not going to happen unless you have put enormous effort into it,” he said. “Enormous planning and enormous money, frankly.” These ballpark trips tend to be meticulously planned out well before pitchers and catchers report, long before the rest of the world even starts thinking about attending a ballgame, by the mad obsessives who have chosen this particular challenge as their own. It’s neither normal nor easy. That’s the point.

“If you go down the ladder, you start to get off the beaten path. You’re going to places like Idaho Falls or Johnson City, Tennessee, that people really don’t go to as tourists.”

Chasers spend the winter mapping driving routes, identifying cheap hotels, and seeking out those glorious days where they can take in an afternoon game in one city and a night game in a second one nearby. These overstuffed trips mean rainouts can be a killer: A postponed game on a trip to the Pacific Northwest once forced chaser Charles O’Reilly, who visited ballpark 159 in 2017, to fly from his home in New Jersey to Oregon the next year just to see the short-season Class-A Eugene Emeralds.

For many chasers, the planning itself is something of a hobby, and the late-summer release of the various leagues’ schedules is eagerly awaited. “It’s almost like Christmas,” says Sean MacDonald of Queens, New York, who completed his tour of Minor League ballparks in 2017. Last year, he took in a game at the new stadium in North Augusta to keep his number at 159.

A tour of Major League parks takes a traveler exclusively to stadiums in or near major cities. But an attempt to hit all 159 affiliated Minor League parks — for the record, that number includes the one in Jupiter, Florida, that’s shared by two teams — effectively forces a chaser to explore towns big and small, all across the country. Chasers initially set out on these trips because they like baseball, but the pursuit means that they wind up seeing the country in ways that most people never will.

“In Triple-A,” says MacDonald, “a lot of those are tourist towns—New Orleans, Louisville, Memphis. People are going there for reasons other than baseball. But if you go down the ladder, you start to get off the beaten path. You’re going to places like Idaho Falls or Johnson City, Tennessee, that people really don’t go to as tourists.”

Ask MacDonald about some of his favorite trips and he’ll recall not just standout ballparks but his visit to the Utah Cowboy and Western Heritage Museum at Ogden Union Station; or the hiking trails in Great Falls, Montana; or the James Brown exhibit at the Augusta Museum of History. MacDonald is a Canadian-born Blue Jays fan, and he remembers the shock of first visiting locales with open carry laws just as vividly as he does the experience of watching Vladimir Guerrero Jr. play for the Bluefield Blue Jays in a tiny ballpark on the border of Virginia and West Virginia.

The idea of baseball as the national game is much more persuasive at levels where the stadiums are not named for major financial institutions or tech concerns.

“If every Minor League team is a reflection of its community, then there’s 160 teams that taken together are a reflection of America,” says the Brooklyn-based writer Benjamin Hill, who last season also finished his quest to visit every Minor League park; he chronicled his travels for the MiLB.com-affiliated Ben’s Biz blog. Like MacDonald, Hill says he recognized early on that his journey would be taking him to places he’d never have otherwise visited. “Take Appleton, Wisconsin,” he says. “If you’re not from that area you wouldn’t say, ‘Hey everyone, let’s plan a trip to Appleton.’ But then you go and there’s the farmer’s markets, and a cool downtown, and a Harry Houdini museum. You walk around and you’re like, ‘Wow, I never even gave a thought to this place one way or the other.’”

Some chasers get more caught up in sightseeing than others. When on ballpark trips with family, Kramer tags along on his brother’s parallel quest to visit the oldest bar in every town they visit. After catching the travel bug visiting ballparks, O’Reilly decided to challenge himself further by attempting to visit every county in the contiguous 48 states. Baseball, in this case, was either a gateway drug or just the most convenient justification for a broader wanderlust.

Even the chasers laser-focused on just visiting ballparks can’t help but be exposed to the vibe of a given town, or at least a little local history—the stadium in Coney Island designed to fit in with the nearby beach and amusement parks, for instance, or the one in Montgomery that was built into the city’s historic former train station, or the one in Corpus Christi, where the scoreboard is framed by antique cotton presses that were incorporated into the stadium. Baseball is more than happy to brand itself as America’s Pastime, but at the highest level it is an entertainment business like any other. The idea of baseball as the national game—something fundamentally and uniquely American, and rooted in something deeper than branding—is much more persuasive at levels where the stadiums are not named for major financial institutions or tech concerns.

“Minor League Baseball is just a really cool way for people in the country to get together,” says Wilhelm, the chaser from Traverse City. “Even the small towns wind up with teams sometimes, and it’s a neat way for people to come together in their community, and have something to root for.”

Chasers say that the fans in those parks are usually happy to talk with them about what’s going on in their communities. A common complaint, according to MacDonald, is the taxes that pay for the ballparks themselves. “It’s funny how many times you’ll see that around,” he says. “It’s not something they’re happy about.”

And then there’s the varied views just beyond the outfield walls: of the Wasatch Range, or of Pensacola Bay, or the Charlotte skyline. That last one comes up a lot, because North Carolina tends to be popular with chasers. The scenery is beautiful, but more importantly, the 11 teams there make for an efficient trip.

Chasers share a particular mania, but tend to enter through different doors. MacDonald began racking up U.S. pro venues in 2001, during breaks from work while living in Japan. First he visited every U.S. Major League park, and on subsequent trips added all the venues in the other three major pro sports. This earned him “membership” in what’s now called Club 123. The Minor League tour felt like a natural next challenge.

Wilhelm’s story is similar: In 2007, he visited all 30 big-league parks, and sometime around 2012, decided to start chasing Minor League ones, too. Wilhelm says he’s been to 276 total professional ballparks, including independent-league stadiums and ones that have since closed, and his interest in ballparks isn’t limited to chasing. For years he was an active member of the Navin Street Grounds Crew, a volunteer organization dedicated to maintaining and restoring the site of old Tiger Stadium in Detroit.

Some chasers caught the bug even earlier. Kramer, who is originally from Ohio, says his older brothers took him on a ballpark trip back in 1979, when they visited four Major League stadiums in four days. That turned into an annual Labor Day road trip, which grew into weeklong trips and ten-day trips. Eventually these trips started including Minor League parks, too. “Before you know it, you’re up to 50 or 60 of them,” he said. “You start looking at it, like, ‘well, I might as well see how many we can do.’”

“If you’re doing, say, national parks, generally there’s not new national parks every year. But there’s always new stadiums.”

Different chasers have different strategies for fitting these trips into the rest of their lives, and different rules they create for themselves that help mold their personal pursuit.

Wilhelm works four days a week at a casino in Traverse City and takes two 10-day vacations a year, which means he can plan out a bunch of weekend trips plus a pair of longer ones each summer. He says that he works extra hours in the off-season to put away money for his travels, but also keeps his expenses down wherever he can.

“Almost every game I buy the cheapest ticket, just to get in the door,” says Wilhelm. “I’m always looking for the cheapest flights, the cheapest hotels. My little game is I like to try to get free parking wherever I go, and I’d say 90 percent of the time you can find that, if you’re willing to look for it. When you’re doing it constantly, it all adds up.”

MacDonald scaled back his chasing last year after the birth of his first child. He’s not particularly interested in re-visiting venues he’s already seen and doesn’t care much about independent-league parks, but in addition to keeping his Minor League list active, his current project is seeing the Blue Jays and Maple Leafs play at every venue in their respective leagues. Since his daughter was born, though, he won’t go away for more than one night at a time unless his family travels with him. His daughter’s Minor League ballpark count currently stands at two: Wilmington, Delaware, and the Fishkill home of New York’s Hudson Valley Renegades, where they took in Pirates and Princesses Day last August.

Other chasers can’t get enough of the combination of baseball and travel, even if it takes them back to locales they’ve already seen. Charles O’Reilly, for instance, says he’s “basically retired,” which gives him considerable flexibility to plan out the sorts of trips that working-stiff chasers can only dream of. Last year, he completed a 40-day, 42-ballpark, 46-game road trip that took him as far west as Modesto and as far east as Norwich, Connecticut. The total stats: 14,600 miles, one blown tire, and, he’s proud to say, no traffic citations. He, too, looks for budget hotels — anything with a bed, shower, and WiFi will do. “And with any luck at all, they have a continental breakfast, too,” he says. “That saves me more time in the morning.”

North Augusta was the only new ballpark in affiliated baseball in 2018, but chasers have already begun looking ahead to the coming season, when three new ballparks are set to open. For a very specific subset of baseball fans, three very different cities — Amarillo, Las Vegas, and Fayetteville, North Carolina — are the country’s hottest new vacation destinations, though true completists might also swing by Clearwater, Florida, where the Dunedin Blue Jays will play most of their 2019 home games while their regular ballpark is undergoing renovations.

“It’s an ongoing quest,” says MacDonald. “If you’re doing, say, national parks, generally there’s not new national parks every year. But there’s always new stadiums.”

Joe DeLessio is a journalist from New York City. Follow him on Twitter @