Community Corner

'Stop The Sting' Jellyfish Study Offers Hope For NJ Bay, Lagoon Users

The three-year study found there is a relatively simple way to help reduce the population of stinging bay nettles that anyone can do.

LAVALLETTE, NJ — In 2013, as residents of the Jersey Shore were picking up the pieces and trying to rebuild in the aftermath of Superstorm Sandy, there was another group of residents whose lives were turned upside down: Bay nettles.

The destruction of bulkheads and docks and waterfront structures caused a significant loss of habitat for jellyfish polyps, the stage where they grow and reproduce while attached to hard surfaces, said Paul Bologna, a biology professor at Montclair State University and New Jersey jellyfish expert.

The result was a significant decrease in the population of bay nettles, the stinging jellyfish that show up in New Jersey's bays and lagoons each summer, chasing swimmers and waders from the water. The effect lasted for a few summers before the population rebounded.

Find out what's happening in Toms Riverwith free, real-time updates from Patch.

It got scientists thinking, Bologna said. "If we can disrupt the polyps, can we reduce the population of bay nettles?"

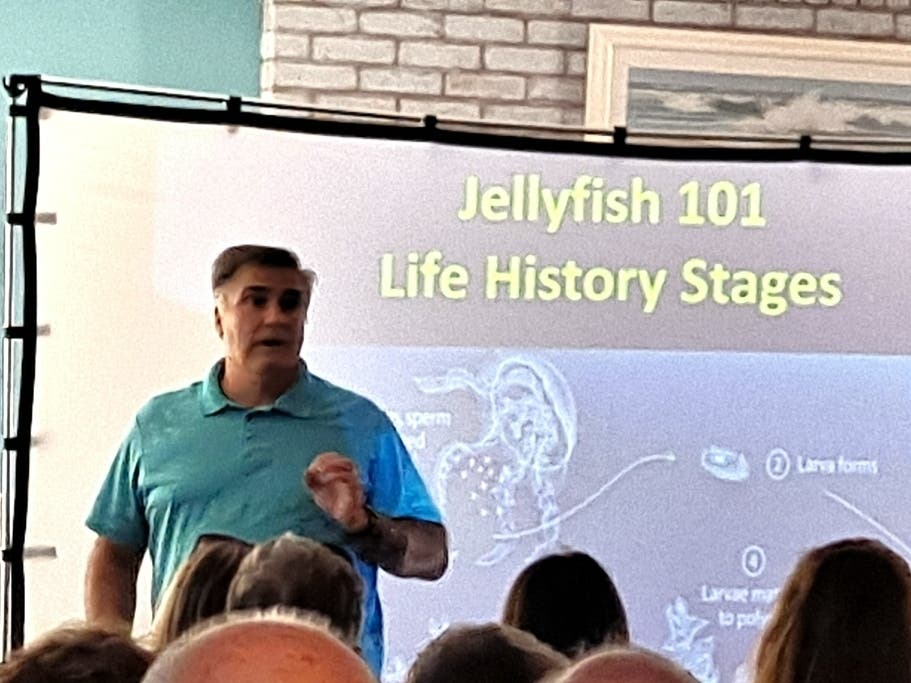

The answer is yes, Bologna said. He spoke Wednesday night during the annual Save Barnegat Bay meeting, presenting the results of Stop the Sting, a three-year study that looked at the effectiveness of disrupting jellyfish polyps in reducing the population in bays and lagoons.

Find out what's happening in Toms Riverwith free, real-time updates from Patch.

The study, which was funded in part by a grant from the state Department of Environmental Protection along with donations to Save Barnegat Bay, involved powerwashing and scrubbing floating docks and bulkheads at two lagoon communities in Berkeley Township, and monitoring an unscrubbed lagoon neighborhood in the Forked River section of Lacey Township.

Jellyfish polyps love to attach themselves to hard surfaces, Bologna said, and will cling to everything from concrete and clam shells to vinyl bulkheads and floating docks. The new materials used for bulkheads and docks that don't use toxic creosote have created additional habitat for polyps, he said.

"Nothing grows on creosote," Bologna said, noting the irony.

The scrubbing and power washing, performed by divers with the Berkeley Township Underwater Search and Rescue squad, aimed to remove bay nettle polyps, which attach themselves to hard surfaces to ride out the winter months. In the spring, as water warms up, they begin cloning themselves in what Bologna described as a "pancake stack" of jellyfish.

Each polyp can clone itself into 500 to 1,000 jellyfish, he said, and dozens of tiny polyps can attach themselves to various structures for that process.

The study began in the summer of 2021, Bologna said, with him and his students at Montclair State University sampling the two Berkeley lagoons to be scrubbed and the Forked River lagoon to see how many ephyrae — young jellyfish — were present. From the fall of 2021 through 2024, the lagoons where the Berkeley divers group scrubbed showed a tremendous decrease.

"After nine months of scrubbing (in 2021 and early 2022) there were no ephyrae" in their water samples in June 2022," Bologna said. The population in the Forked River sampling, where there was no scrubbing, continued to rise.

As the scrubbing has continued, the population of ephyrae has remained minimal; what few show up are a result of currents and the fact that they swim, he said.

"So we know scrubbing disrupts the polyps' life cycle," Bologna said.

Addressing other jellyfish species requires determining where their polyps attach themselves, he said, and some of the research Bologna's students found some attach to algae, opening entirely different possibilities for reducing the population.

For now, Bologna said, the goal is to spread the word about the Stop the Sting findings and encourage residents, property owners, communities and towns to get involved with scrubbing down bulkheads and docks to disrupt polyps and the life cycle.

If people remove their floating docks from the water during the winter and scrub down bulkheads and pilings, they can kill the polyps, meaning there will be fewer bay nettles in the summer, he said.

The Berkeley Township Underwater Search and Rescue divers will do the scrubbing and have put out word that they are looking to expand the program. Read more: 'Stop The Sting' To Expand Locations In Barnegat Bay

"We need funding," said Carl Mattocks, president of the search and rescue divers group.

"Everything is time and money," Bologna said, but added the more areas that are scrubbed, the more the bay nettle population will be kept in check.

"It really does have an impact," Bologna said.

Read more about the Stop the Sting program on the Save Barnegat Bay website and on the Berkeley Township Underwater Search and Rescue project page.

Get more local news delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for free Patch newsletters and alerts.