Silkscreens to touchscreens: we found horror on Google Maps this week. What would Warhol say?

At first, the bodies were outside; then they were in our televisions; then they were on the covers of our magazines, sharing space with our biggest and most golden celebrities – who occasionally also died, and were photographed - and then, in time, they were on our computer monitors, online. Soon, we found that we barely had to look for them at all. The bodies, by then, were inside our houses, at all times. They were on the screens of our telephones, or else they were on our workplace monitors, or they were on a late-night segment of the news – a war-zone broadcast. They had found their way in through the tubes - insidious, silent, and bloated – and like poltergeists, they had set up residence in our peripheral vision, forever.

“I guess it was the big plane crash picture,” Andy Warhol said of the start of his Death and Disaster series. “The front page of a newspaper: 129 DIE [IN JET]. I realized that everything I was doing must have been about death."

“I guess it was the big plane crash picture,” Andy Warhol said of the start of his Death and Disaster series. “The front page of a newspaper: 129 DIE [IN JET]. I realized that everything I was doing must have been about death. It was Christmas – a holiday – and every time you turned on the radio they said something like: ‘Four million are going to die.’ That started it.”

Eventually, we stopped ever really seeing them, but we still felt unaccountably afraid: more than anything, we were uncertain as to whether the bodies were multiplying, or whether they were simply moving closer. In December of last year, America’s New York Post ran the image of a man mere seconds from being hit by a subway train on their cover; the previous year, the death-shots of Colonel Gaddaffi had run in the Guardian. Luka Magnotta, the Canadian Psycho, approximated the absolute apex of modern hype - the ideal blend of sex and violence and Aryan pornography star. On the silver screen, torture porn thrived as a genre; the New French Extremity brought the karo-syrup gore of the slasher trash-flick into the arthouse.

And so, the bodies piled up at the extremes of our collective eyeline. We absorbed the atrocities around us in small, safe increments, as if undergoing a vaccination against the violence of the outside world, until one of the bodies – one of the many - was found this week, in an unexpected place: on Google’s satellite mapping program, next to a railroad track. This particular body belonged to a teenage boy – a Kevin Barrera, who had been shot and killed in 2009, and whose murder had remained somewhat mysterious. "When I see this image, that's still like that happened yesterday,” his father was quoted as saying, in almost every morsel of coverage. “And that brings me back to a lot of memories." As a tribute, the internet carried on circulating the screen-grab [Dazed covered the story, too – ed].

An online trade exists for ghoulish images from the Google Maps site, but this was one which had previously escaped our notice: less bombastic than the prostitutes, the dying mammals and the costumed robbers adopted for art and Buzzfeed pieces. the boy simply lay there.

On Google News, “Kevin Barrera 2009” yields no results beyond the hits for this story. The body of the child remains, but there is little detail about his life – the newsfeed pictures suggest a smiling, round-cheeked boy, much loved by his parents. An online trade exists for ghoulish images from the Google Maps site, but this was one which had previously escaped our notice: less bombastic than the prostitutes, the dying mammals and the costumed robbers adopted for art, and for Buzzfeed pieces, the boy simply lay there – a small, pale-shirted casualty, in a ‘hicksville’ location.

Google – sensing the deeply unusual, Now-ish nature of the issue – has vowed to remove the image: "Google has never accelerated the replacement of updated satellite imagery from our maps before, but given the circumstance we wanted to make an exception in this case." This exception, however, fails to prove the rule. Sky News’ coverage of the story includes a photograph of Barrera, in which he is holding a Nerf gun, proudly, to his chest. In the background of the image is a Christmas tree.

(“It was Christmas,” Andy Warhol might say. “A holiday.”)

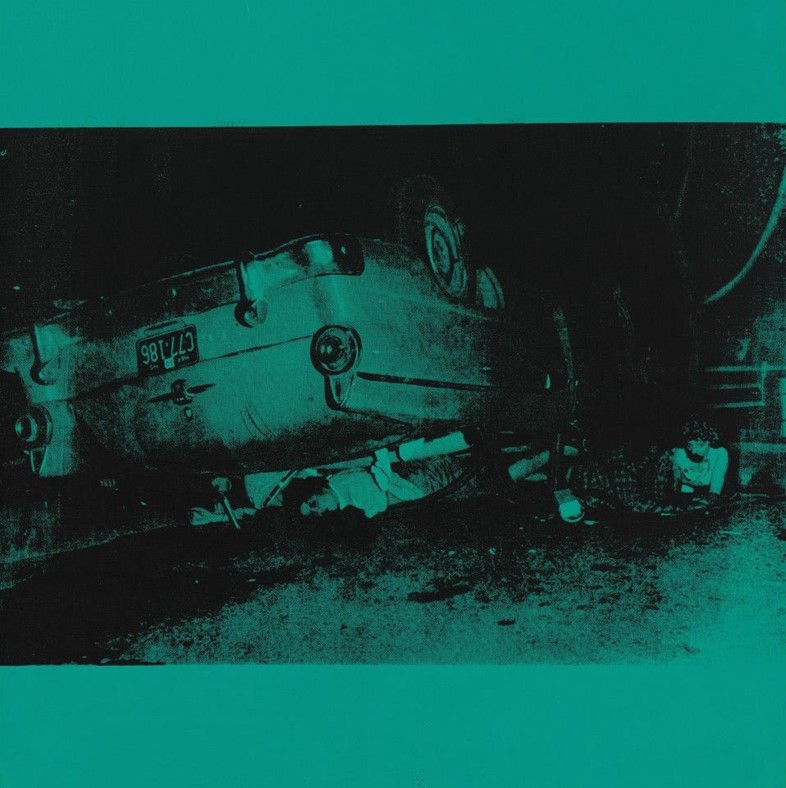

While creating the Death and Disaster series, Warhol turned an image from a 1963 edition of Newsweek into one of his patented hyper-Pop silkscreen canvases. It depicted a fatal automobile collision, and its original caption read: “End of the Chase: Pursued by a state trooper investigating a hit-and-run accident, commercial fisherman Richard J. Hubbard, 24, sped down a Seattle street at more than 60 mph, overturned, and hit a utility pole. The impact hurled him from the car, impaling him on a climbing spike. He died 35 minutes later in hospital.”

Silkscreens, of course, are considered passé in the modern age. Thankfully: we have the internet for this, now. And the bodies continue to creep in.