“Do you know the way to Belvedere Castle?” Bill Skarsgård and I have been walking for an hour and forty-seven minutes, winding our way aimlessly around Central Park on a moody New York City morning in April. Over the bridges, around the baseball fields, past the amphitheater, and through the nature sanctuary. Twice.

Now we’re suddenly facing a middle-aged, brunette woman in workout clothes who’s looking at us expectantly. Neither of us, however, has the faintest idea how to locate Belvedere Castle, a Central Park landmark and former lookout tower completed in 1872 and designed in the style of a miniature, well, castle.

Skarsgård freezes, leaving me to apologize to our fellow park walker for not knowing which way she should head. She hurries along, none the wiser about whom she just met. It’s the first time we’ve interacted with any of the hundred or so people we’ve passed this morning. And while there is an inherent compliment in being asked for directions in Manhattan—who doesn’t hope they pass for a New Yorker?—Skarsgård mainly just seems relieved that it wasn’t a fan making an approach.

It poured down rain all morning, and clouds still hang low over the city, trapping thick, lukewarm air. The gloomy weather somehow feels appropriate given the thirty-three-year-old’s upcoming slate of films. In August, he’ll lead a second—bigger, bloodier, sexier—adaptation of The Crow, among the most hotly anticipated reimaginings in recent memory. And come Christmas, he’ll sink his fangs into audiences with his interpretation of a notorious cinematic monster, Count Orlok, in Nosferatu. Unbothered strolls through the park, in other words, may soon be a thing of the past. “I hope not,” Skarsgård says to the suggestion.

Born and raised in Stockholm, Skarsgård has spent time in Manhattan over the years, but this is his first visit to New York in half a decade. After breaking big in his home country in high school and then heading for Hollywood, he bounced from movie set to movie set and TV show to TV show before eventually settling down again in Stockholm. Along the way, he’s built one of the most curious and compelling catalogs of any actor his age.

Just as he disappears into his Manhattan surroundings today, he disappears completely into his roles, from an evil clown (Pennywise in the behemoth horror series It) to a French Cajun thug (the Marquis in John Wick: Chapter 4) to a profoundly troubled World War II veteran (Willard Russell in Antonio Campos’s The Devil All the Time). Wearing a matching navy set of loose-fitting (but structured) trousers, a quarter-zip sweater, and an even more structured pullover with dark sneakers, he’s a total chameleon despite his six-foot, three-inch frame and bright-green eyes.

But it’s not just his ability to transform that surprises; it’s his desire to embrace such characters at all. Deeply flawed and occasionally even disgusting, these are not the roles that make a man a movie star. That’s okay—Skarsgård is searching for something else.

You know the name. Skarsgård. You've known it since his father, Stellan, broke out in the U. S. nearly thirty years ago, in the midst of an international career that boasts more than a hundred projects—Good Will Hunting, Mamma Mia!, and Dune: Part Two among them—and has earned him a Golden Globe as well as a suite of European acting awards. Also since his oldest brother, Alexander, first spiked pulses as Eric Northman on HBO’s racy vampire fantasy True Blood. And since his second-oldest brother, Gustaf, became the star of every dad’s favorite History-channel show, Vikings.

Bill is the fourth of Stellan and My Skarsgård’s six children. Five boys, one girl. (He has two younger half siblings from his father’s second and current marriage to Megan Everett-Skarsgård.) The family’s home—an apartment in Södermalm, the southern island in Stockholm, one floor beneath their cousins and across the street from their grandparents—was busy and loud. “It was just, constantly, open doors, running up and down the staircase,” he recalls. But it wasn’t only Skarsgårds crowding around the dinner table. “All of us, in our respective groups, would be the ones bringing friends back home to us,” Bill says. It wasn’t typical in Sweden, he explains. “The only families I could properly relate to were my immigrant friends from the Middle East.”

When Stellan booked jobs, he and My would decamp to set, all their kids in tow. Los Angeles, Canada, Southeast Asia—until high school, everyone went. My, a medical doctor by profession, would tutor her brood while Stellan worked. The culture shock became the thrill.

By the time Bill was born, Alexander and Gustaf, fourteen and ten years his senior, respectively, had each already logged their first onscreen credits. But his brothers’ embrace of Stellan’s profession made his own decision to pursue acting harder, not easier, Bill admits. “When I was a teenager, I didn’t like the idea of being number four.” He tried other endeavors, but nothing stuck. And though he was hesitant, Swedish casting departments and directors weren’t. “The next Skarsgård” has a certain appeal, and one by one, movies and TV shows that spiked his curiosity presented themselves. “I felt like, ‘Okay, I may not want to be an actor, but I want to make this movie.’ ”

This article appeared in the Summer 2024 issue of Esquire

His worries about constant comparisons were not totally unfounded. Recalling the headlines and reviews that followed his earliest projects, he says, “Two thirds of all the articles were like, ‘Here we go again....’ ”

Late in high school, Skarsgård was cast in the coming-of-age film Behind Blue Skies, and then he lined up two other roles in projects that would, not through his own design, debut within a year of each other. If that sounds like a young actor’s dream, chances are you’re not from Sweden. Only a few dozen feature films get made annually in the Scandinavian country, and Skarsgård quickly found himself overexposed.

“Sweden is very known for tall-poppy syndrome,” he explains. (For a visual reference: The plant that towers above the rest is the one that gets clipped.) You can be successful but not too successful. “I knew I wouldn’t work in Sweden for like ten years,” he says now.

He made his way to L. A., experienced his first pilot season, and booked Hemlock Grove, a scripted series from the then-nascent Netflix. Skarsgård has worked, almost without a break, ever since. He jumped from production to production—2016’s massive third entry in the Divergent Series, Allegiant; 2017’s Atomic Blonde—each role bigger than the last. And then he booked It.

A second screen adaptation of Stephen King’s 1986 horror novel, the film—the first of two chapters—would go on to become the third-highest-grossing R-rated movie of all time after debuting in late 2017. But before it could shatter sales records, director Andy Muschietti needed to find his Pennywise. He was open to anyone—male or female, young or old—for this version. They just had to be able to terrify.

The role was unlike anything else on his résumé at the time, but Skarsgård wanted it. On his way to a callback, he drove through Los Angeles, his face caked with self-applied clown makeup, testing out different maniacal laughs until he felt the character begin to burble inside him.

“Something mesmerized me,” recalls Muschietti of Skarsgård’s earliest interpretation of the monster. The actor had a boyish energy that the director felt was key to the portrayal, but it was his way of sending shivers down your spine that stayed with the filmmaker. Or, as Muschietti says: “One second he can act all cute, and then the next, there’s something ancestral and dark that just appears. His ability to transform is mind-blowing to me.”

Euphoria creator Sam Levinson, who worked with Skarsgård on 2018’s Assassination Nation, says something similar: “His charm pulls you in, but there's always an unpredictability lurking under the surface.”

For those of a certain age, there was, at the time, already an iconic portrayal of Pennywise haunting their memories: Tim Curry’s, from the 1990 miniseries version of It. That was the measuring stick that audiences, critics, and the general online commentariat were using to evaluate the young Swede. The pressure was on. Skarsgård understands just how much today, but when he accepted the role, he had absolutely no fucking clue. “When you are twenty-six, you don’t feel young at all, but now, looking back at it, I was a kid,” he says. “It was fairly early on in my career to take on something that had so many eyeballs and expectations on it.”

And a marketing stunt by the studio sparked a baptism by fan fire. As Skarsgård remembers it, “They did a thing that I felt was kind of mean.” Before he started filming, the studio released a photo of him in costume to drum up excitement. Social-media feeds went wild, and fan blogs tore him apart. “I was so incredibly nervous to start this job, and then the Internet is having so many hateful opinions on the weird, strange look of the thing,” he recalls.

He couldn’t sleep. The insults echoed through his mind all night long. “This looks so stupid.” “Lame.” “Boooo.” But, in time, the haters forced him to make a decision that would change his approach to acting forever. “You can only make this performance to please yourself,” he says of the new attitude. He made himself both the creator and the audience in his mind, and he figured out what he wanted to see. What he thought was cool. Unsettling. Terrifying.

“It unlocked something in me,” he admits. “And it gave me the confidence that I can take on any challenge.” Long pause. Little smile. “At least, that’s how I feel when I accept these things.”

Do you ever have doubts? The answer comes fast: “Every movie I do,” he says, laughing.

Skarsgård is obsessive when he works. Spiraling so far into the psyche of his character, he usually comes up only to ask why the hell he’s putting himself through this at all. “Usually, I’m like, why am I doing this to myself? I should not do this. It’s not healthy for me.” He starts daydreaming about alternatives—like becoming an accountant. “Something more stable,” he says.

Of course, he wouldn’t really leave his profession. Couldn’t. “There are those moments,” he says, “when you’re totally lost in the moment. When during the whole take you never thought once about the fact that you’re doing it. You aren’t acting.” It’s beyond that, he explains. “Just being.”

For a guy who has worked as consistently—and in such colossal projects—as Skarsgård, you’ll find surprisingly few interviews with him on the Internet. A handful of podcasts. Just a couple profiles. He doesn’t mince words: “I just don’t really enjoy them.” (No offense taken.) Being Bill Skarsgård may be interesting, but the way he sees it, that’s a reality to protect, not reveal.

Fame has made him uncomfortable since he was too young to even know what fame meant. “I remember going in grocery stores and my dad would go, ‘Can you go grab the milk in this-or-this aisle?’ And once I walked away from him, I would hear people be like, ‘Do you see who’s here?’ ” Skarsgård couldn’t understand why his own father’s arrival caused such a stir, but he knew he didn’t like it. “I felt violated; strangers are whispering and talking about my dad.”

Skarsgård is in a long-term relationship with Swedish actress Alida Morberg, and they share a five-year-old daughter. He’s been able to protect the space around him and his family fairly easily, he says. He’s also managed to get darker and, delightfully, weirder in terms of the roles he accepts. The vengeful Mark in Assassination Nation. The zany Mickey in Villains. The supernaturally evil The Kid on Hulu’s Castle Rock (which is also connected to the Stephen King universe). The braggadocious Swedish outlaw Clark Olofsson on Netflix’s Clark. The CGI supervillain Kro in Marvel’s Eternals.

Not every project has worked, but Skarsgård’s contributions usually have. “He has inhabited those roles, so he disappears,” says Rupert Sanders, who directed him in The Crow, “and that’s a testament to how good he is. You don’t see the actor anymore.”

There might be a reason for that. “It tends to become life-and-death for me,” says Skarsgård of his approach to each character. It may not be sustainable, he says, but it’s the only way he knows. And if he’s being honest, he enjoys the hunt. As he says, “I want to explore my own limitations.” Explore. It’s the exact word that shows up when I speak to many of his former collaborators.

From Muschietti: “What I saw in Bill that really excited me was his desire to explore.”

Campos: “The people that you tend to admire tend to be on a path of exploring what they’re interested in, regardless of public opinion. And Bill is excited by making those choices.”

With his leading role in The Crow, however, all eyes will be on Skarsgård. Expectations for the movie are sky-high, and this time, it’s his own face—big eyes, turned-up nose, rueful smile—front and center. It’s fair to say that he has mixed feelings about this proposition. “There’s definitely worry about that,” he admits, speaking about what the release may do to his public profile. More eyeballs. More attention. More whispers at the grocery store. “I’m trying to view the fame aspect as a challenge and navigate through it in a way that I’ll find happiness,” he says. “I really don’t think my line of profession is a recipe for happiness or contentment. Not a lot of us are happy. And the more the fame is increased, the more turbulent and scary life becomes.”

Skarsgård tries to keep those worries out of his mind when he’s picking jobs. He’s adamant that he is building his career not with some grand vision but rather role by role. Yet when you look at his filmography, it is undeniable that the stories he is drawn to are often twisted—occasionally, as he says, even “pure evil.”

“He doesn’t want to be a Hollywood heartthrob,” says Sanders. “And that’s the legacy of a long career to me—if you’re not involved in the Hollywood machine and you’re creating roles that you are emotionally connected to. It’s like buying art. You just buy what you want to see on your walls and not what you think is going to make you money. And he’s just got a weird taste in art.”

David Leitch, who directed Skarsgård in Atomic Blonde, feels he still has much more to show. “He’s an actor that I believe can do anything,” the filmmaker says. “It’ll just be a matter of time before he does something that reflects his comedic chops.”

Skarsgård frequently gets asked why he favors such dark characters. There is a subtext to the question: Why is a guy who looks as good as he does, who could earn a hell of a lot of money playing lovable hunks and heroes, making himself so damn terrifying, so damn unlikable—and perhaps unmarketable—onscreen? Well, those roles are boring. Diving into the psyche of Count Orlok, a vampire raised by Belial’s own hand, though? Now, that’s fun. “You have to use all of your imagination to try to come up with something cohesive,” he says of the appeal.

It’s also a two-way street, he reminds me. You can only book what you get offered, after all. “I’m drawn toward them the same way they’re drawn toward me.”

Now is a good time to divulge a secret: Bill Skarsgård, the scariest clown ever to fill the big screen at your local theater, is not a fan of scary movies. “I’m not a huge horror buff.” Turns out he’s more of a comedy guy. His most watched film? The Big Lebowski.

Skarsgård’s early education in movies began in the same spot as most: on the couch with Dad. The entire family is close, he emphasizes multiple times when we speak, but Skarsgård found more common ground with his father than with his mother when he was young. Also, by necessity, more space. “We’re six kids,” he says, “so you kind of pick what side of the bed of your parents you sleep on. And my sister’s a year and a half younger than me, so I got pushed off from Mom’s side fairly early onto Dad’s.”

Skarsgård doesn’t seem entirely comfortable discussing his mother—one of the few subjects he’s reticent about. “My mom’s gone through a lot,” he says tentatively as we make our way around Belvedere Castle—which, by happy accident, we’ve stumbled across in our wanderings. “I’m very proud of who she is today. She’s devoted her life to help recovering alcoholics and addicts, which she’s gone through herself.” He doesn’t elaborate further.

So what were the Skarsgårds watching back in the day? Sergio Leone westerns, Kurosawa creations, Charlie Chaplin films, and Coppola’s catalog. All of it. Stellan had taste, but he also had rules. And as for what was on the screens at home, he was adamant: “Whenever violence was romanticized or unrealistic—like, ten head kicks in Power Rangers—he was vehemently against it,” says Skarsgård.

We want what we can’t have, don’t we? Once Skarsgård was able to download and stream on his own, he discovered he loved those sorts of films. “My dad was morally against violence. So I wasn’t allowed to have toy guns,” he says. “But I’ve never held those ideals. I grew up in a different time. I don’t think playing a violent video game makes you a violent person.” Actually, he adds, “I’ve always found violence fascinating.”

Skarsgård still considers himself a movie lover, but he’s streaky when it comes to sitting down to watch something he hasn’t seen. He also goes through prolonged periods when he isn’t watching anything at all.

When I ask him about his hobbies—or anything he generally enjoys—he answers similarly.

What about TV? “In and out.”

Do you drink? “Off and on.”

Do you like when home is a loud and busy place, or do you crave quiet? “I go in and out of different phases.”

What do we know? He likes to cook. And, describing what downtime looks like for him, his partner, and their daughter, he says, “We’re adventurers.” They’re with him in New York right now. Last night, they had a dinner of “tortellini and chicken parm” at Patsy’s.

Skarsgård does admit to having at least a few vices—coffee and nicotine mainly. Weed as well. In February, TMZ reported that he had been arrested in October 2023 for cannabis possession at Arlanda Airport in Stockholm. That definitely wasn’t his first time carrying it, but “it was my first time getting caught,” he quips, adding: “There’s ways to go in Sweden in terms of legalizing it and just generally being very conservative in that aspect.”

He loves living near his family. One by one, each of the adult children has moved back to Stockholm. He and his siblings get together often and, as everyone’s family has grown, they’ve come to basically overrun the Skarsgård country home. “Christmas is like twenty-five people,” he says proudly. “That’s just immediate family.” He jokes: “We’ll have to get our own little island and call it Skarsisland in the future.”

He also very clearly enjoys being a dad. Throughout our time together, he peppers his answers to non-family-related questions with references to his daughter. The way she used to tuck in all her stuffed animals for bed before she could even talk, for example, is proof to him that women are wired to be more empathetic than men. He mentions how her arrival helped him put down permanent physical roots. And one of the first questions he asked me, in the lobby of his hotel before we set out for our walk, was if I have kids of my own.

He’s a deep thinker as well. The Crow costar FKA Twigs says Skarsgård spent most of his off days during production “training and contemplating.” And he acknowledges that the mysteries of the universe frequently disrupt his mind. “I have obsessively thought about those things,” he says. Littler pause. Bigger smile. “I’ll let you know when I have found the answers.”

There is a hearty, vocal contingent of fans who believe The Crow should have never—and I mean never—been made for the screen again. Partly because director Alex Proyas’s 1994 outing rocks. High-octane and surreal, it stood apart from anything else that had ever hit theaters. But the protective veil is cast more because it was both the breakout film for Brandon Lee (son of martial-arts icon Bruce Lee) and the role that ended his life. Then twenty-eight years old, the actor was killed in an on-set accident when a prop gun malfunctioned.

Skarsgård echoes the sentiment that the movie’s marketing team has shared elsewhere: This is not a remake of the earlier film but instead a second adaptation of the graphic novel. The 1994 movie had a straightforward revenge plot. The 2024 version, helmed by Sanders (Snow White & the Huntsman), is at its core a love story. Not a rosy one, though. “It’s romantic in the same sense as a Cure song,” says the director. “There’s a melancholy there.” Audiences see Skarsgård’s Eric and Twigs’s Shelly meet, fall in like, and tumble into love before she comes to her gruesome end. Only then does his quest begin. It wrestles with doubt and desperately claws at life’s big questions. Why are we here? What happens to us when we die? What would you give up to save the one you love?

That’s all true—I’ve seen it—but have you been online lately? None of that will temper fans and critics who want to stack the two films and the two leading men against each other.

Director Chad Stahelski, who worked with Skarsgård on John Wick: Chapter 4 (“I think he’s my best villain ever,” says the filmmaker of the Marquis), has a unique lens to offer on The Crow. He and Lee were close friends and ran in the same circle of actors and stuntmen. And when Lee died, with much of the film not yet finished, Proyas called on Stahelski to stand in for Lee in a number of scenes. (It’s a common misconception, Stahelski says, that he was involved as Lee’s stuntman from the start.)

“I had to sit for weeks with Alex Proyas and watch all of the footage,” he recalls. “Face replacement was not very big at the time—you had to mimic everything.” Painstakingly, and very much while in mourning, they finished the work.

How did you feel when you found out the movie was coming back—and that Skarsgård was playing Eric? “When I heard Bill was doing it, I was like, ‘That’s a good take.’ ” He adds, “I knew Bill was going to bring something different. Bill’s got that ethereal nature that makes him feel out of this world, or from another planet or existence.”

Back in Central Park, Skarsgård opens up about the fact that now, two years after filming wrapped, he feels a certain distance from the work. As with most topics, he is refreshingly candid. That includes when discussing the ending of The Crow. I won’t spoil what happens, but I will tell you that Skarsgård would have voted for a different conclusion. Why film it the way they did? It made the path for a sequel easier, his answer suggests. “I personally preferred something more definitive.”

The film was shot in Prague over the course of about four months. Mainly at night. It was long and grueling but gratifying. The project marks Twigs’s first lead role, and she fully credits Skarsgård with making the experience a rewarding one. “Working with Bill has changed the trajectory of my career, really,” she says. “He gave me a lot of confidence. He was very tender with me.”

And once Sanders got past the initial shock of Skarsgård’s diet and daily intake (“He eats about a pound of raw meat,” says the director. “He’s like a kind of caged beast. Every meal, he’d order tartare”), the only surprise left was the sheer scale of the actor’s commitment.

Skarsgård arrived to set directly from another shoot and did four straight demanding months. No complaints. Very few off days. And then, “on the last night of shooting, I said to him—we had this agricultural tank filled with black syrup—and I said, ‘Bill, I know it’s eleven at night and it’s not very warm in there, but would you get in that oil and thrash around and scream and come up out of that oil as if you’re possessed?’ ” Sanders says.

What do you think happened next?

Skarsgård may be ambivalent about the ending of The Crow, but he visibly brightens when speaking about Nosferatu, director Robert Eggers’s reimagining of the infamous 1922 silent picture. That film, an unauthorized adaptation of Bram Stoker’s Dracula and a groundbreaking work in the horror genre, starred Max Schreck as the Transylvanian monster. It changed the course of cinema entirely—both through its influence on future directors and by helping to solidify future copyright laws. When the new film arrives on Christmas with Skarsgård in the role of the famously undead count, it will be the culmination of an eight-plus-year hunt for the lead.

He first met Eggers right after the director debuted The Witch, which Skarsgård loved, in 2015. Real life, it turned out, was even better than the movies for the actor. “It’s kind of like a date, right?” says Skarsgård, recalling the meeting. “That’s the closest thing I can compare it to. You get a crush on someone—you can’t stop thinking about that person. I’ve only had it a few times, but that was so true with Robert. It was like, ‘Whatever this guy does, I just want to be a part of anything that this guy is making.’ ”

Eggers mentioned Nosferatu then, and Skarsgård was eager for basically any role. First, he read for Friedrich Harding, a German ship merchant and a supporting (human) male character. That didn’t work, but he landed an offer for Thomas Hutter, the main protagonist. Great news. Anya Taylor-Joy was attached, and things were moving ahead—until they weren’t. The movie fell apart and came together again more than once in the following years. Scheduling. Funding. Who knows what—that’s showbiz. And when it finally came together for the last time—the time when it was really going to get made—Skarsgård was left wondering if he still had the role.

When news emerged that Nosferatu was ramping back up, “I wrote this long, pleading email to Robert,” he remembers, amused by the memory. Referencing Hutter’s fictional hometown, he adds, “I think the title was like Wisborg in Flames or something. I was just desperate to rekindle this thing and be a part of it.”

“It was very earnest,” Eggers says a week later over Zoom, equally pleased by the memory. “They say an expressionist artist doesn’t wear his heart on his sleeve; they cut it out from their chests. It was raw, but it wasn’t too much.”

Even so, Eggers still went in another direction, casting Nicholas Hoult in the role of Hutter this go-round. Skarsgård didn’t give up hope. There were other roles, right? Hell, he’d already read for Harding way back when. But that part soon went to Aaron Taylor-Johnson.

Skarsgård made peace with it. Sort of. “ ‘Robert and I are done!’ ” he jokes about how he felt at the time. “It was a fiery romance, but it never flourished!” Then, in a move that, to Skarsgård, felt like it came out of nowhere, Eggers reached out and asked him to read for Count Orlok. When the creative team was originally casting for the vampire, men in their mid-forties were being considered. Skarsgård would have been twenty years shy of that. But as time passed—and as Eggers and his team spoke with others in contention for the iconic role—the vision for the character transformed.

Skarsgård’s beauty was a boon, says the director. It might be nice, he thought, to have audiences actually be attracted to the monster. But it’s not what nabbed him the part. Skarsgård read for the role multiple times. By self-tape. Over Zoom. In the studio with his hair slicked back and fake nails glued on. He tested out voices and sent them over piecemeal in voice notes. He did one makeup test, and then another. As Eggers puts it, that’s when the light flicked on. “Somewhere in that second makeup test, I was like, ‘He’s become the character.’ It was eerie to see in the footage. Anything he did, anywhere he turned or looked, you were like, ‘He’s got it.’ ”

Some eighteen months later, the cast, which had lost Anya Taylor-Joy but had gained Lily-Rose Depp, arrived in Prague to film. Skarsgård was comfortable there. He’d shot The Crow nearby and stayed at the same hotel for both productions. But this headspace was different. Darker. More sinister. He worked with an opera singer to bring his voice down to its lowest possible pitch and spent three to six hours every day in makeup and prosthetics. The set was serious. Tense, even. Skarsgård was largely isolated from the rest of the cast, during prep as well as during the shoot. He felt like the character deserved it. Demanded it. “It took its toll,” he says now. “It was like conjuring pure evil. It took a while for me to shake off the demon that had been conjured inside of me.”

The level of darkness that Skarsgård was able to channel was stunning, says Eggers. “I remember early on, him trying to talk to me about what it meant to be a dead sorcerer—and I’m into some pretty heavy occult shit, but he was on a different level.” Laughing, he adds, “I was like, ‘This sounds accurate, but I don’t know how to converse about this with any fluidity.’ ”

Orlok’s look has, until now, been kept completely under wraps. And Skarsgård is careful to leave it that way in conversation. What can he share? “I do not think people are gonna recognize me in it,” he reveals.

I have questions. Well, just one: Is this vampire sexy? Long pause. “He’s gross,” Skarsgård begins, slowly. “But it is very sexualized. It’s playing with a sexual fetish about the power of the monster and what that appeal has to you. Hopefully you’ll get a little bit attracted by it and disgusted by your attraction at the same time.”

As we leave Belvedere Castle behind and walk back to his hotel, Skarsgård returns to a common theme in our conversation. As much as he enjoys the moviemaking process, he doesn’t care that much for the film industry and all that comes with it. Even acting sometimes gives him the ick. “There’s something gross about it,” he says.

But for now at least, it’s all about the next role. From New York, he will head to Toronto, where he’s filming something. “I don’t want to spoil it,” he teases. Maybe it’s just a coincidence that a few days later, when I get Muschietti on the phone, he too is in Ontario’s capital—which happens to be where both It movies were filmed. And earlier, when I’d asked Skarsgård if he would be willing to play Pennywise again, he offered only a sheepish “maybe” in reply. Have there been discussions about when that may happen? “Maybe.”

What happens after Skarsgård finishes filming in Toronto is up in the air. Offers are coming and going. And while he’s open to anything, there’s really just one thing he wants. “I need time to refuel and figure things out before I embark on the next thing,” he says. He could use a visit to Skarsisland, in other words, before he goes exploring again.

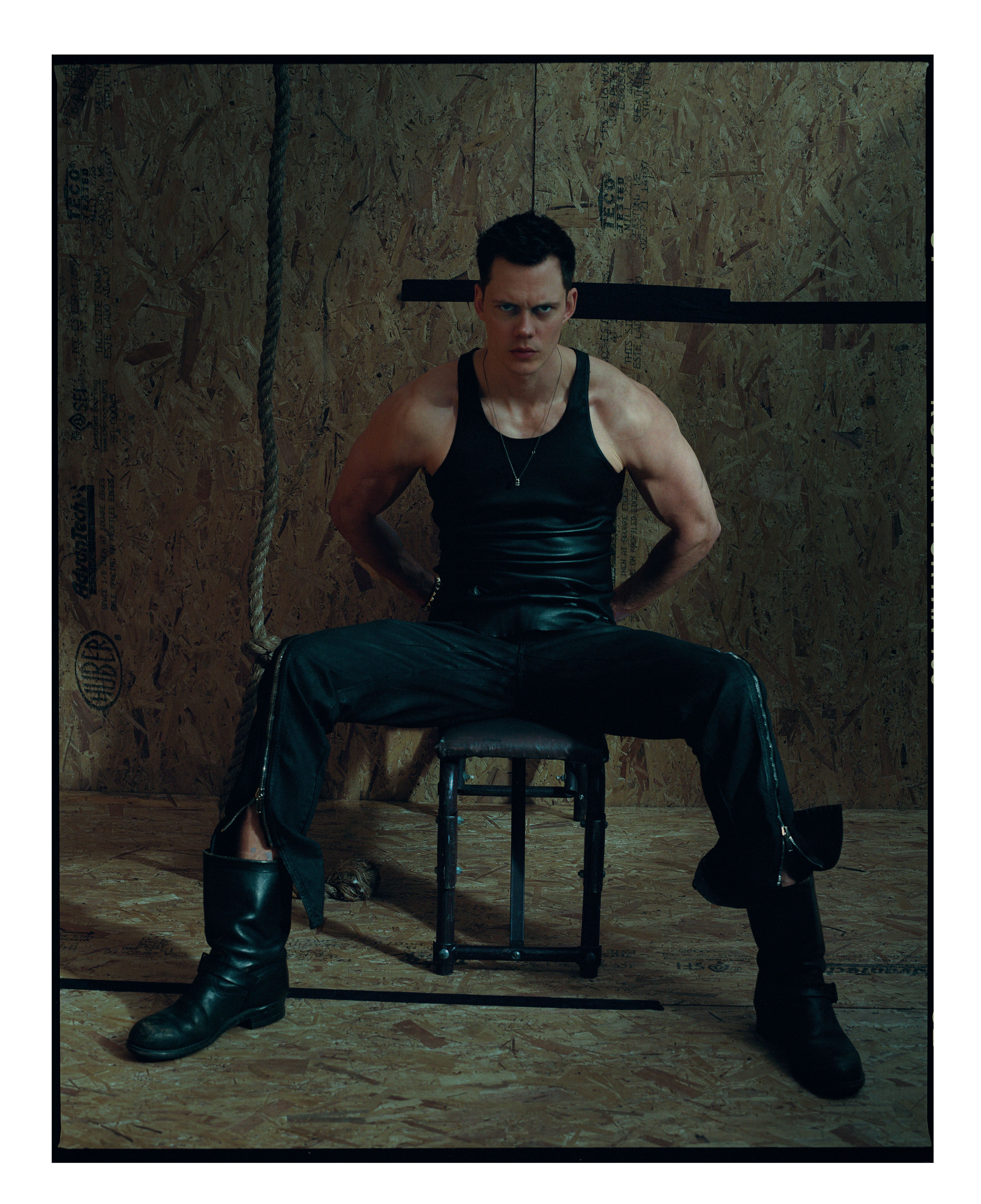

Opening image: Tank and pants by Rick Owens, available at Bergdorf Goodman; cuff and boots, available at the Cast NYC (worn throughout); necklace by Werkstatt:München (worn throughout).

Cover: Jacket and trousers by Dolce & Gabbana; vintage T-shirt, stylist’s own; belt by the Leather Man, NYC; necklace, bracelet, ring, badge pin, and wallet chain by Werkstatt:München; cuff by the Cast NYC.

Story by Madison Vain

Photographs by Norman Jean Roy

Styling by Bill Mullen

Hair by Kevin Ryan

Grooming by Ginger Ryan

Production by Boom Productions

Set design by Michael Sturgeon

Tailoring by Todd Thomas

Design director: Rockwell Harwood

Contributing visual director: James Morris

Executive producer, video: Dorenna Newton

Executive director, entertainment: Randi Peck