Gabriel Garcia Marquez’s lost novel asks important question about what happens when an author dies

The revered author’s final manuscript ‘Until August’, written in the throes of dementia, is to finally be released by his estate – despite demands from Marquez to ‘shred it’. Robert McCrum asks if there’s a case to be made for ignoring an artist’s wishes

The big draw for the launch of the inaugural 2006 Hay Festival in Cartagena was Gabriel Garcia Marquez. Colombia’s walled city-fortress was renowned as his home. The buzz was: Come to the festival where you’ll meet “Gabo”.

Led by Rosie Boycott and Christopher Hitchens, a posse of bookish thrill-seekers duly showed up to discover that the great writer was nowhere to be seen, still less spoken with. There were rumours, but no hard news. Perhaps he was visiting Castro (a fan); or on the road; or what? The festival came and went; Gabo remained as elusive as the hippogriff, but the fever was understandable.

Marquez, who died in 2014, remains a colossus, especially in Spain. One Hundred Years of Solitude (1967) sold an astonishing 50 million copies and made its author a rock star.

At the height of his fame, one ecstatic critic declared that this founding document of magical realism was “the first piece of literature since the Book of Genesis that should be required reading for the human race”.

Subsequently, The Autumn of the Patriarch (1975), Love in the Time of Cholera (1985), with many subsequent novels and novellas, confirmed Marquez, who dominated a literary boom that includes Cortazar, Fuentes and Vargas Llosa, as “the best writer in Spanish since Cervantes” (Carlos Fuentes).

After 1982, when he was awarded the Nobel Prize, Marquez continued to explore themes of love and death, loss and nostalgia, but his best work was done.

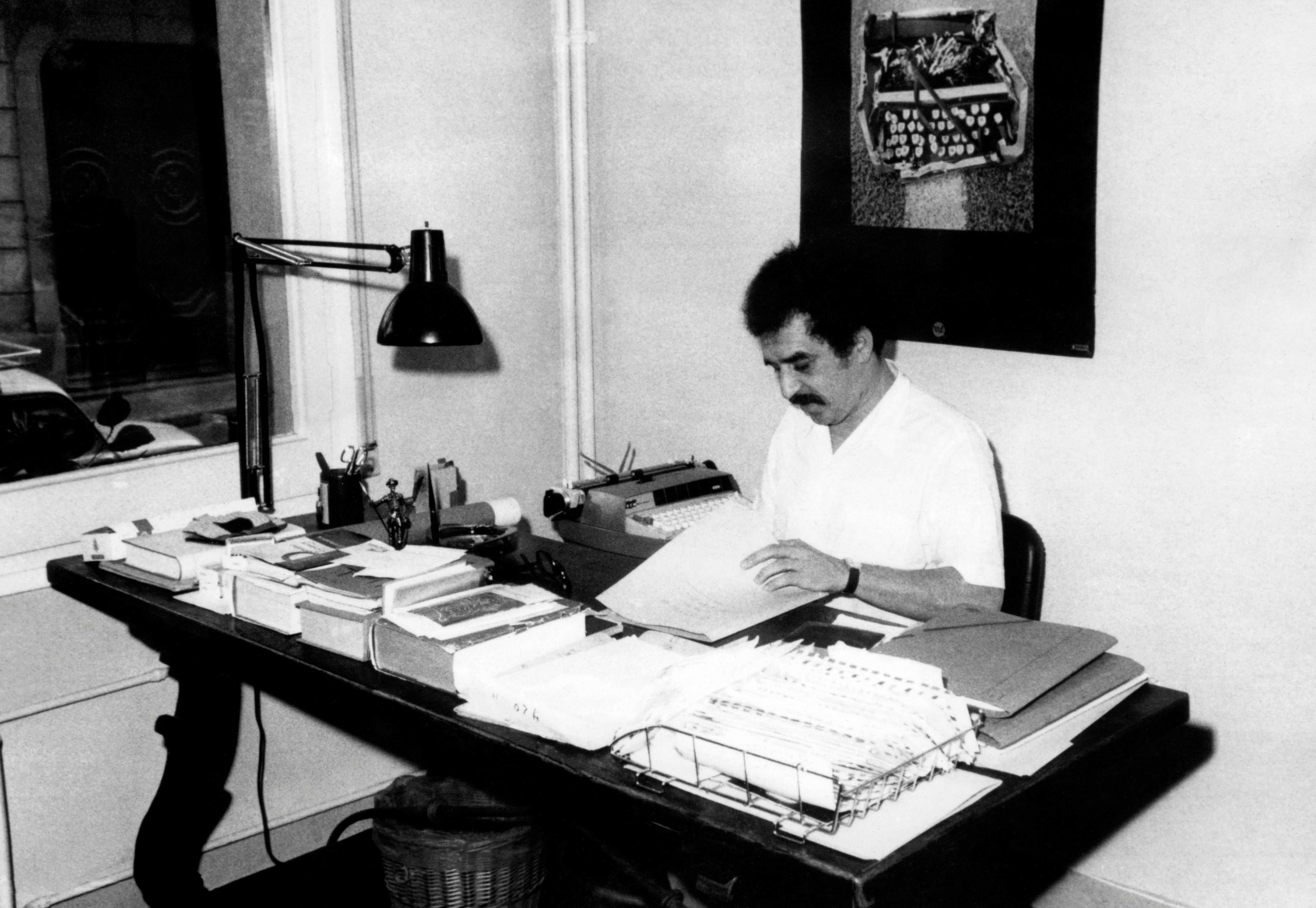

In 1999, he was diagnosed with cancer, a condition which morphed into dementia. In his final years, the novelist of memory and solitude became the prisoner of failing powers. Obsessive about his work, as he’d always been, he devoted himself to a project that began as We’ll Meet in August and finally ended with this novella, Until August.

What posthumous control can the author exercise over his or her work? This hoary question dates to Virgil, who asked that the unfinished Aeneid be destroyed. (The emperor Augustus intervened on behalf of posterity.)

The issue recurred when Franz Kafka wanted his friend Max Brod to burn a collection of manuscripts which included both The Trial and The Castle. (Brod found reasons to ignore this request.)

More recently, this perennial topic cropped up when Vladimir Nabokov’s estate authorised the publication of the author’s unfinished 18th-century novel The Original of Laura, a manuscript on index cards which he had stipulated should be destroyed posthumously.

Yes, he was suffering from dementia, but not so mad that he could not detect his failing powers. For his fans, ‘Until August’ will be a posthumous amuse bouche, no more or less

The inevitable commentary that looms over questions of authorial intent surfaces again with the publication of Marquez’s novella, Until August. On this decision, his estate is admirably frank. In his declining years, Gabo had said, “This book doesn’t work. It must be destroyed.”

On that subject, there are two points of view. The unsentimental, practical one goes like this: Marquez said destroy it, so shred it. The more elevated, and frankly commercial, response goes: the question of whether or not to follow an author's wishes about the fate of their work after death is both difficult and painful. We offer this text to the reading public in a spirit of devotion to his memory.

You pays your money and you makes your choice. The question is complicated by Marquez’s genius. Especially for Spanish readers, the author of Love in the Time of Cholera is a literary giant for the ages. In South America, everything he wrote is a treasure. The matter is complicated, of course, by the market value of any new Marquez fiction.

Burning, or shredding Until August would not merely deprive Marquez scholars such as Cristobal Pera of useful academic employment. To his heirs (Rodrigo and Gonzalo Garcia), who describe a text with “a great many wonderful achievements”, it would be like torching a trunk full of $20 bills.

Twenty dollars, indeed, is the hook that animates Until August, a slender work of precisely 106 pages, fleshed out with a preface from the family and a devout academic afterword.

On page one, we meet Ana Magdalena Bach, wittily described as a “reader of love stories by well-known authors”, en route to her mother’s grave. Slight as this novella must be, it opens with the gorgeous texture his readers associate with Marquez, prose that’s both haunting and limpid. It’s 16 August, in the season of “heatwaves and crazy downpours”. The mood of this opening is heavy with nostalgia, grief, and the secret discords of a musical family that’s not quite as it seems.

If nothing else, the lazy afternoon it takes to read Until August will send you back to Marquez’s masterpieces in all their spectacular majesty. Ana Magdalena is travelling with Bram Stoker’s Dracula; she’s an attractive woman, alone in a tourist hotel.

Marquez has cast his spell. As if it’s the most natural thing in the world, she falls into conversation with a “Hispanic gringo”, and takes him up to her room where, “for the first time in her life” she has sex with a stranger, a mid-life fantasy that’s about solitude, longing, lust and death.

After this, she “would never be the same”. The blissful, transgressive mood of her encounter unravels the morning after the night before when her anonymous lover leaves $20 on the dressing table.

What follows her shattered fantasy, depending on your point of view, falls somewhere between vintage Marquez or Mills & Boon. Where Gregory Rabassa and Edith Grossman were translators who imbued Marquez’s exotic prose with a touch of magic, that’s missing in Anne McLean’s more pedestrian rendering.

Still, there’s a reading here in which the aftermath of her one-night stand is all in Ana Magdalena’s head. On the page, with diminishing returns, Until August becomes a tale of self-revelation through addictive betrayal.

On successive “16 August” visits to her mother’s island grave, Ana Magdalena retraces her steps, and indulges her lust, a mixed bag of seduction that culminates with a bishop.

Through the shame of her infidelities, she discovers that she’s living her mother’s life and become the prisoner of her memory. She resolves to break free. In a macabre and shocking conclusion, she exhumes her mother’s body, and goes home to her family with a bag of bones, a new woman.

This reader closed a fragile text with the kind of regret (sorrow braided with frustration) of which Marquez was a master.

Yes, he was suffering from dementia, but not so mad that he could not detect his failing powers. For his fans, Until August will be a posthumous amuse bouche, no more or less.

But it’s also a masterclass in the terrible truth that great writers in extreme old age almost inevitably produce an unconscious parody of themselves. They’re there, but not there.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments