John Cooper Clarke, beloved Bard of Salford: ‘If you gave me access to the internet, you’d find me dead in six weeks under pizza boxes’

He was the toast of the punk scene in the 1970s, touring his performance poetry with the Buzzcocks, the Sex Pistols, and the Clash. Fifty years on, he’s still going, with a new tour, a new collection, and a fan base that includes the Arctic Monkeys. John Cooper Clarke talks to Fiona Sturges about giving up heroin, why writing poetry should never be mistaken for therapy, and why he’ll never own a computer or a smartphone

When the young John Cooper Clarke told his family he was going to be a professional poet, they were aghast. “For them it was a worst-case scenario: I was going to die in the gutter,” he says. “Poetry has never been regarded as a reliable engine of wealth, so I was advised against this course of action by everybody who meant well.”

But while Clarke has endured some career troughs, there have been enough peaks to keep him in business for 50 years. He is the man who invented punk poetry and who incorporated everyday life – tracksuits, bedsits, trips to the seaside, how you never see a nipple in the Daily Express – into spleen-venting, often hilarious verse. He has toured with Buzzcocks, the Sex Pistols, The Clash, The Fall, Joy Division, and Siouxsie and the Banshees, and grazed the top 40 singles chart with his 1978 spoken-word single “Gimmix! (Play Loud)”.

Now, at 75, the man known as “the Bard of Salford” (he has always preferred “the bargain-basement Baudelaire”) has never been so in demand. Next month he performs a series of live dates in the archly titled Get Him While He’s Still Alive! tour – “I like to think it has a note of urgency about it,” he cackles. Meanwhile this week sees the release of a new poetry collection, What, his fourth book. He has even found favour with a new generation, thanks in part to the band Arctic Monkeys who turned his poem “I Wanna Be Yours” – “I wanna be your vacuum cleaner, breathing in your dust/ I wanna be your Ford Cortina, I will never rust” – into the closing ballad on their 2013 album AM. The song recently reached 1.7 billion streams on Spotify. “I don’t know what that means but it ain’t nothing,” Clarke grins.

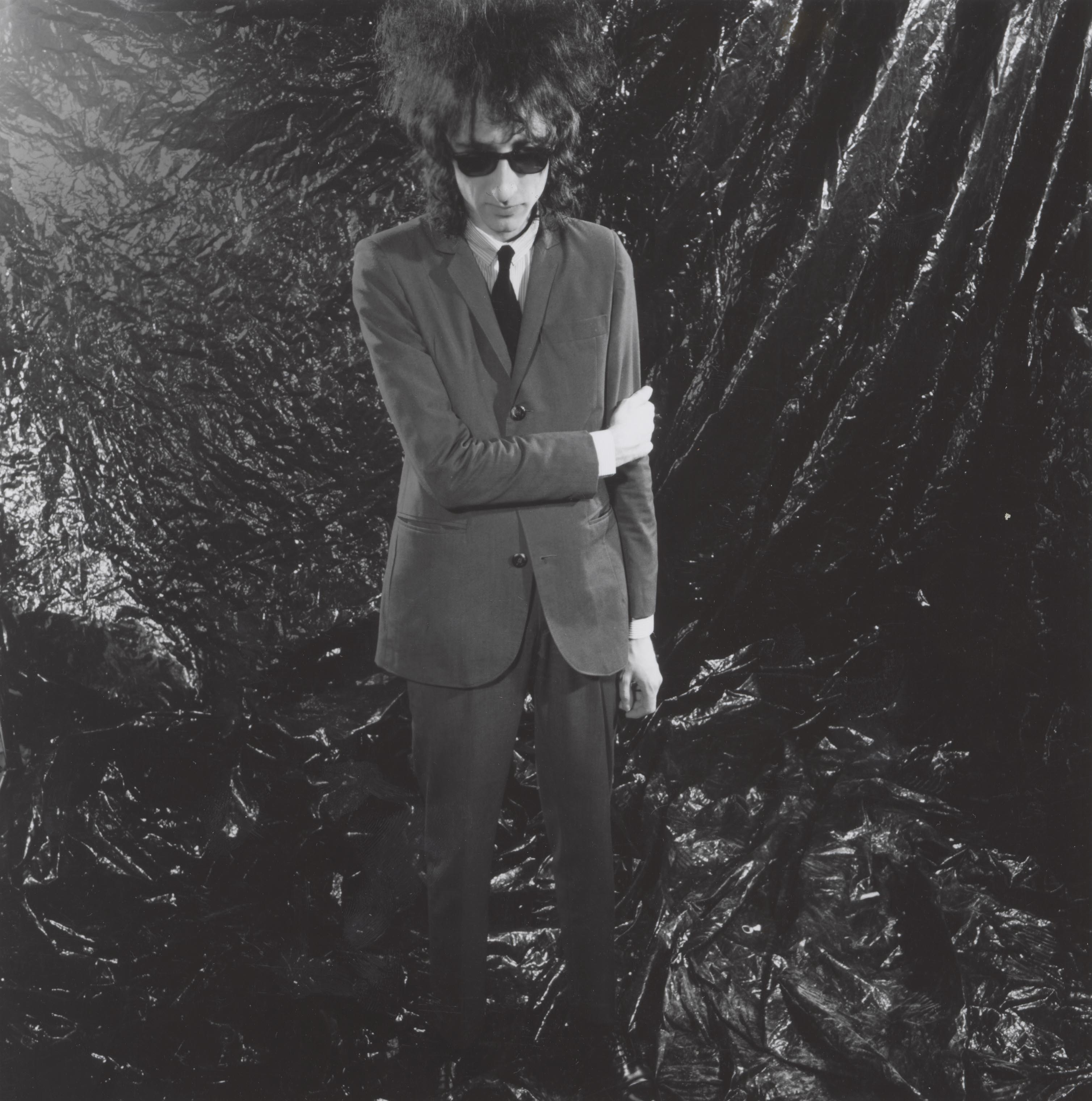

When we meet over video call, I find him ensconced at a friend’s recording studio outside Colchester in Essex, parked amid banks of keyboards and piled-up amplifiers. Looking dapper in a black baker-boy cap and his signature shades, he has today swapped his customary dark suit for a tweed blazer, button-down shirt, and maroon silk scarf with matching handkerchief. He couldn’t be more delighted that his fans include teenagers and twentysomethings as well as old punks. He puts his enduring popularity down to taking highbrow and lowbrow art “and sticking it through the same mincer. I think people are very literate about that kind of thing, far more than they used to be”. He notes how Baudelaire “didn’t make any distinction between the smutty humour of the music halls and the opera houses of high society. These were overlapping worlds to him”.

What covers subjects from Elvis, chlamydia, necrophilia, and the late racing commentator Peter O’Sullevan to the delights of Sheffield and Manchester’s Curry Mile (“Drunk chicks blow chunks out the back of a stretch”). It is vintage Clarke: wry, dry, full of smart wordplay and pithy observation. “Blue Collar Wallah”, for instance, is a portrait of a “heteronormative handyman” who is a “two meat and one veg guy, potatoes never kale” and who is painfully out of step with the zeitgeist. “I have a great deal of sympathy for him as I know a lot of people like him,” Clarke explains. “But don’t mistake him for me – I’m not handy for a start. If you’re a poet and you’re looking for an angle on [a theme], then you have to be an adopter of positions.”

Meanwhile, “Smooth Operetta” is about the youth tribe once known as “casuals”, identifiable by their Farah slacks and slip-on shoes. Clarke is similarly exacting about his wardrobe, though he prefers three-button suits “in the mod style. I went to see The Birds in 1965 where I looked at [their guitarist, the future Rolling Stone] Ronnie Wood and thought, ‘He looks good,’ so I modelled myself on him”.

Clarke is a walking encyclopaedia of popular culture from the early 20th century onwards – our conversation yields references to Fifties quartet Dion and the Belmonts, The Beano, Raymond Chandler, Keith Waterhouse’s Billy Liar, music hall stalwarts Stanley Holloway and Harry Champion, and the Lock, Stock and Two Smoking Barrels actor Jason Statham, who gets a mention in “Blue Collar Wallah”. Growing up in Salford in the 1950s, Clarke spent much of his childhood at the movies – there were seven cinemas within walking distance from the flat he shared with his parents and younger brother. He was also a compulsive reader, inhaling everything from his mother’s copies of Woman’s Own to his uncle Denis’s crime novels. At the age of eight, he contracted tuberculosis, which gave him his first taste of opiates (he had morphine on tap). On leaving hospital, he was sent to recuperate with a relative in Rhyl where it was hoped the sea air would do him good. There he spent long days alone in the library and at the local funfair where he got his first taste of Elvis through the sound system.

By the age of 12, Clarke was reading Dumas, Zola, Dickens, and his beloved Baudelaire. School was rough, especially for a sickly child; he only went because his mother told him she’d be put in prison if he didn’t attend. Had he played truant, he might have missed the lessons of his English teacher, John Malone, who turned him on to the idea of poetry read out loud. “He seemed to know instinctively that poetry had always been a phonetic medium, and dynamically so,” Clarke wrote in his 2020 memoir I Wanna Be Yours. “He didn’t ham it up, there was no need. He let the language do the talking. The main consideration is what a poem sounds like. If it doesn’t sound any good, it’s because it isn’t any good. That is the big lesson I learnt from Mr Malone.”

He was in his late twenties by the time he began touring with punk bands. Before that point he had worked variously as a cutter in a clothing factory, a construction worker, a compositor at a printworks, and a fire watcher in a naval dockyard. He never told his workmates about his poetic ambitions, even though in his social life, Clarke notes in his memoir, he was “an open book”.

Having tried and failed to get his poems published in magazines, he decided to take them directly to the people and perform them live. After rattling around Manchester’s jazz and comedy circuits, he got his first paid gig in the early 1970s from the controversial comedian Bernard Manning, who ran the Embassy Club in Harpurhey. Then punk came to the rescue. “[Former Buzzcocks singer] Howard Devoto said to me: ‘You should be doing the punk rock venues, you’ll fit right in,’” Clarke recalls. “There were only two rules, sartorially, with punk – no beards, no flares – which meant I ticked both boxes. So I took my existing repertoire [of poetry] and speeded it up. That was my house style.” To him, punk “felt like home”, not least because “up until that point, no pop record was ever a hit because of the lyrics. But unusually the lyrics were important [on punk records]. Think of the Ramones: ‘Now I guess I’ll have to tell ‘em / That I got no cerebellum.’ These were my type of songs.”

I’ve gotta say, heroin was fabulous so it’s a miracle I ever gave it up at all... But being clean and having the life that I have now, I wouldn’t swap that with the life of a junkie

Success on the punk scene overlapped with him using heroin and, as punk petered out, he became a full-blown addict. Once, in between tour dates in Scotland, he caught the sleeper train from Edinburgh back to London to collect heroin from his dealer. Then he travelled straight back up to Scotland for his next performance. Clarke’s memories of this period are understandably hazy, though he recalls being skint and unable to write. “There used to be a tedious saying in the hippy era,” he says. “It went: ‘If you’re not part of the solution, you’re part of the problem.’ And with narcotics, I’m definitely part of the problem. I’ve gotta say, [heroin] was fabulous so it’s a miracle I ever gave it up at all. If it wasn’t fabulous, it would be easy to stop. But being clean and having the life that I have now, I wouldn’t swap that with the life of a junkie. No way.”

Clarke tends to write in the afternoons – “I’d tell you I do a full working day, but I’d be bullshitting.” He doesn’t wait for inspiration to strike. “That’s OK for amateurs but not when it’s putting food in your family’s mouths. From an early point, I intended to become a professional at this, so I’ve never regarded poetry as a way of dealing with things. If you’re dealing with something traumatic there’s always something more sensible to do than write a poem.” As a poet, he adds, “your best friend is idleness. You have to be able to fixate on some very flaky, abstract things. But idleness is a difficult thing to maintain if you have a conscience and if you live with others”.

These days he lives in Essex with his French wife Evie, with whom he has an adult daughter, Stella. He and Evie met in the late Eighties when he got stranded after a live show; after he missed the last train home, a mutual friend asked if Evie could put him up for the night. Touring aside, he lives a quiet life: “I’m the most normal guy on earth. I don’t trouble myself with world politics, but I do keep my eye on the council. I’m a neighbourhood guy.” He doesn’t own a computer or a smartphone – “I’ve never had any of that s*** and now it’s too late,” Clarke hoots – he relies on Stella to keep him in the loop about anything he might find interesting. “The thing is, I know too much already and I could do with forgetting some s***. I think that was the attraction of heroin, but it didn’t work.” One of his flaws, he continues, is “a lack of restraint. It’s hard enough to drag myself away from the TV. If you gave me [access to the internet], you would find me dead six weeks later under a pile of pizza boxes, and I’m not ready to go yet”. He pauses. “I’ve got things to do.”

‘What’ is published by Picador on 8 February. Get Him While He’s Still Alive! opens on 5 March at Norfolk Wells Maltings Theatre and then tours. For more information visit: johncooperclarke.com

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments