‘Fear was part of the pleasure’: How Steven Spielberg mined his dark side to make Jurassic Park

As the beloved family film celebrates its 30th anniversary this summer, Geoffrey Macnab says why ‘Jurassic Park’ was more than just a colossal blockbuster hit – it was a window into Spielberg’s soul as both a filmmaker and a man

What happens when dinosaurs and humans, two species separated by 65 million years of evolution, are suddenly thrown together? The answer, judging by Steven Spielberg’s Jurassic Park (1993), is two-pronged: the humans rake in over $6bn at the box office over the next three decades and the long-gone dinosaurs enjoy a new lease of life.

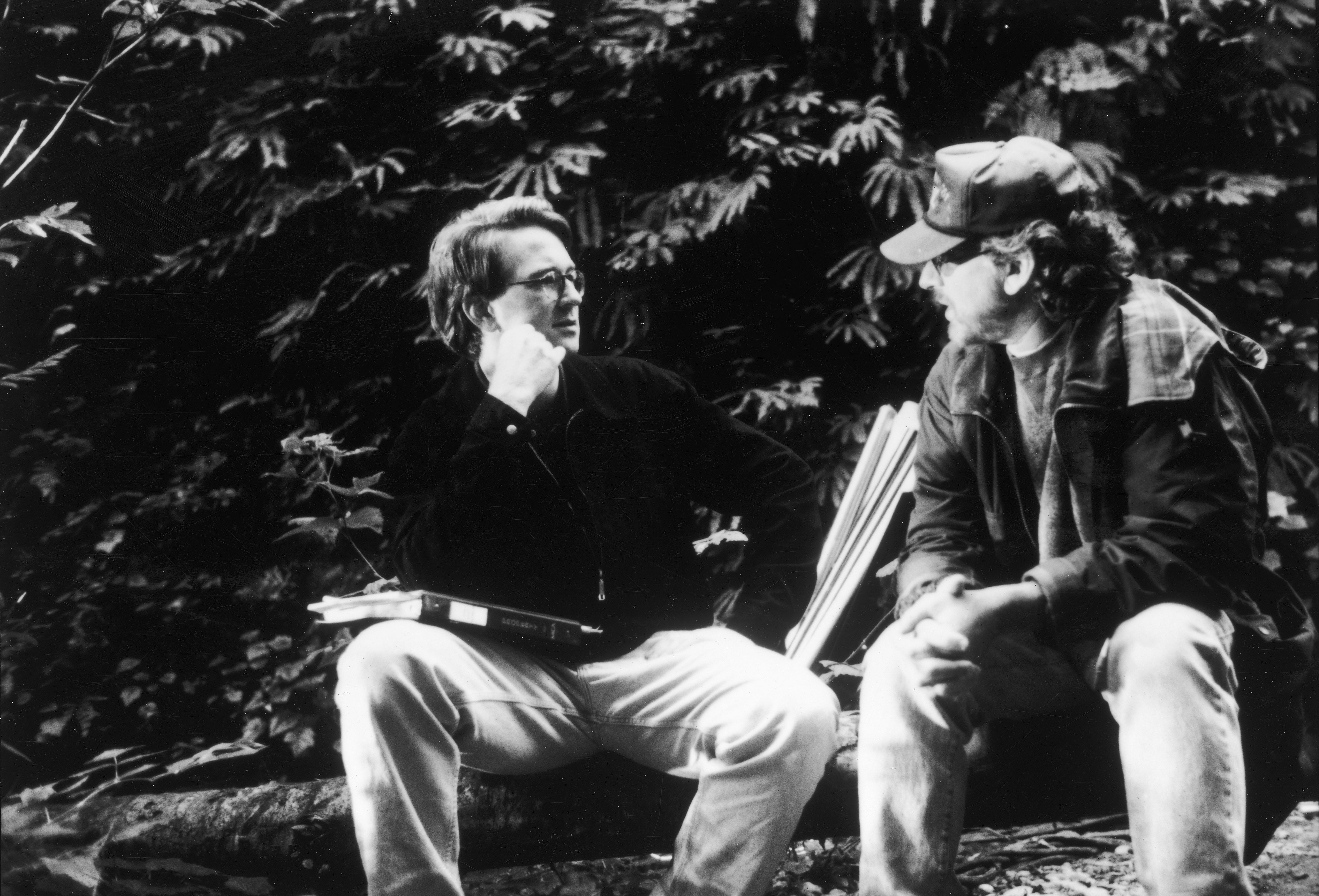

“I have no embarrassment in saying that with Jurassic I was really just trying to make a good sequel to Jaws – on land. It’s shameless. I can tell you that now,” Spielberg struck a surprisingly self-deprecating note when reflecting on his film’s astounding success a year after its release. In some ways, Jurassic Park, which launched one of the most successful franchises in movie history, is the quintessential Spielberg movie. It both pulls together his pet obsessions and reveals the director in all his many contradictions. Famously, it is also the film Spielberg was editing in the evenings when he was on location in Poland shooting his other very acclaimed, though tonally very different Holocaust drama Schindler’s List (1993).

Jurassic Park, which is returning to the big screen next month to mark its 30th anniversary, is an action-adventure romp. It’s a matinée movie made with the same relentless energy and wit as Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981) – and yet it has some searing observations to make about human greed and hubris. It even boasts its own Oppenheimer moment. The obnoxious computer genius Dr Nedry (Wayne Knight) keeps a photo of the “father of the atom bomb” on his desk. Spielberg makes sure that viewers get a good look at the notorious scientist moments before Nedry unleashes the Jurassic monsters on the world.

In his recent autobiography, one of the film’s stars Sam Neill, who plays palaeontologist Dr Alan Grant, said he struggled to figure out what makes Spielberg tick. Before shooting began, the actor asked someone who knew the director well “for some insight”. In response, he was told: “You have to understand [Spielberg] is part wonder-filled child and part ruthless Hollywood mogul.” Spielberg could be cruel, on screen and off. Those who have worked with him testify to how hard he pushes his crew. “You’d run from one set-up to the next because he has got it all worked out how he wants to do it,” one technician recalled of the breakneck pace at which the director generally operates.

Watching Jurassic Park, it’s hard not to be struck by the insouciant way in which Spielberg shows Martin Ferrero’s character, the unctuous lawyer Donald Gennaro, being bitten in half by a T-Rex while sat on the toilet – where he had scampered off to, leaving the kids to fend for themselves. The monster muscles its way in through the rickety walls. The poor man cowers within. The Tyrannosaurus stretches down, picks up Gennaro in its teeth and begins to masticate, chewing through the lawyer as though he’s a long piece of stringy toffee. It’s a brilliantly shot sequence, bloodcurdling and darkly funny, and one that hints at a cruelty within the director. Spielberg often enjoys finding unusual ways to kill off characters he doesn’t like. He’s the type of filmmaker who might enjoy pulling the wings off flies. He likes scaring viewers, too. Witness, for example, the scene in which someone is lending a helping hand to paleobotanist Dr Ellie Sattler (Laura Dern). Moments later, Ellie finds herself holding a severed arm.

As a kid, the future director was bullied at school and subjected to antisemitic abuse. In turn, he used to play pranks on his sisters and later spoke of his pleasure in “torturing” them. A psychological explanation for his sometimes callous behaviour behind the camera might speculate that he is finally getting symbolic revenge on those who used to torment him.

Spielberg possesses obvious similarities with Jurassic Park’s showman protagonist John Hammond (Richard Attenborough), an avuncular but fiercely driven figure determined to create the greatest theme park in history. According to Spielberg’s biographer, Joe McBride, the director identified closely with Hammond, admitting that he shared the character’s “dark side” – “an all-encompassing passion for his work, sometimes at the expense of family responsibilities”.

McBride tells me Spielberg “was so much like Hammond that he found it hard to separate himself from him” and so he deliberately ”softened” the fictional character. Versions of Hammond appear across Spielberg’s body of work: he shares traits with both the UFO fanatic played by Richard Dreyfuss in Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1977) and the distracted, career-driven dad Burt (Paul Dano) in The Fabelmans (2022). Neill’s character is yet another of Spielberg’s flawed father figures. At the beginning of the film, he is adverse to the very idea of children; by the end, he is surrogate dad to Hammond’s grandchildren.

Spielberg’s relationship with his Hollywood paymasters was also highly ambivalent. Jurassic Park can easily be read as a satire about corporate greed and mindless merchandising. Midway through Jurassic Park, as Dr Grant and the two kids are hiding out in the jungle in terror, Spielberg cuts to show us the theme park’s gift shop. It’s crammed with dinosaur T-shirts, toys, games, and water bottles. The director seems to be highlighting the obscenity of hawking tourist bric-à-brac of these deadly creatures. The counter view, of course, is that this scene served as simple product placement. And it worked, too. Once the movie was released, Universal did a roaring trade selling exactly the same items stocked in the shop.

Young audiences responded both to the film’s shock tactics and to the sense of awe that Spielberg strived to induce in them. The British Board of Film Classification (BBFC) warily gave the picture a PG certificate in spite of its “numerous scenes of threat toward the two child characters”. Mindful of its potential to scare impressionable young viewers, however, a special preview screening was organised for 200 children aged between eight and 11 in an effort to gauge just how traumatising they found the viewing experience. “A report of the event describes the reaction of most of the audience as one of ‘cheerful terror’ rather than ‘genuine anguish’,” the BBFC concluded. The children found the film “good and scary”. They enjoyed it in the same way they might have done a fairground ride. Fear was part of the pleasure.

Arguably, the film’s most disturbing elements aren’t what we see on screen but what we hear – all those feral grunts, groans and roars. Sound designer Gary Rydstrom later told the BBC that the “main roar” made by the T-Rex was, in fact, the amplified squeal of a baby elephant. And that unmistakable sound of the dinosaur chowing down on the lawyer in the loo? That was Rydstrom’s pet Jack Russell with a rope toy between its jaws. Spielberg delights in these moments. He has a knack for characterisation and humour, which arguably far exceeds that of novelist Michael Crichton who wrote the 1990 book on which Jurassic Park is based.

Crichton (who co-wrote the Jurassic Park screenplay with David Koepp) was brilliant at creating intricately plotted thrillers, which popularised often complex scientific ideas. “You got a lesson while you were being scared,” his editor Robert Gottlieb observed of Crichton’s work. “What Michael wasn’t was a very good writer… he could do everything necessary except create convincing human beings.” Spielberg doesn’t have a screenwriting credit on Jurassic Park but he ensured that John Hammond was far more sympathetic on screen than in the novel. It was also his decision to make the lawyer Gennaro cowardly and venal. In fact, dinosaurs account for less than 20 minutes of the film’s two-hour-seven-minute runtime.

Dinosaurs on screen certainly weren’t unheard of. The brilliant designer and stop-motion wizard Ray Harryhausen famously unleashed pterodactyls on the bikini-clad Raquel Welch in One Million Years BC (1966). A few years later, he had cowboys squaring off with a T-Rex in The Valley of Gwangi (1969). Even earlier, special effects supremo Willis O’Brien had brought prehistoric monsters to life in the silent era Arthur Conan-Doyle adaptation The Lost World (1925) and once again in King Kong (1933). Spielberg loved these films. As a child, he had been obsessed with these creatures, so much so that he collected his own dinosaur models.

What distinguished Jurassic Park from its predecessors, though, was the hyper-realism of its monsters. As Spielberg’s VFX team at Industrial Light & Magic later boasted, they were offering “living, breathing, photorealistic dinosaurs the likes of which had never been seen before”. At the same time, the director also called on the services of the brilliant puppet designer and creature creator, Stan Winston, who provided hand-crafted models of the “two-storey tall” T-Rexes.

Jurassic Park was a runaway hit and remains one of the top grossing films of all time. It launched a franchise and inspired a new wave of young would-be scientists to study palaeontology. When it comes to critical discussions of Spielberg’s work, however, the dino-movie always lags behind Close Encounters of the Third Kind, ET, and Schindler’s List . The director himself sometimes downplays its significance. “As you grow older, you just naturally want to turn to stories that take up more serious subjects than, say, big sharks and even bigger dinosaurs,” he wrote in the foreword to a 2012 book written about him by critic Richard Schickel.

Nonetheless, Jurassic Park was a far more personal project than the director was letting on. He was the Tyrannosaurus Rex-loving kid who grew up to be the visionary and relentless Hollywood big shot. The movie lets us into both parts of his personality. If you really want to know what makes Spielberg tick, you can always go to last year’s autobiographical drama The Fabelmans but arguably you’d learn just as much by watching this much-loved creature feature. Critic Pauline Kael once wrote that George Lucas was still “hooked on the crap of his childhood”. The same could easily be said of Lucas’s friend and collaborator Spielberg – but trawling through the detritus of their younger years, both men have always found treasure in abundance.

A 30th anniversary screening of ’Jurassic Park’ will be held at BFI IMAX on 2 September

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments