Why the world’s biggest election year could be a bit of a damp squib

While more than 2 billion people are expected to vote in elections this year – from the US to Russia, and Taiwan to Tuvalu – the irony is that little is expected to change, writes Sean O’Grady. Indeed, Keir Starmer could be the ‘freshest’ face on the world stage

Democracy is a wonderful thing, and it seems that the world can’t get enough of it. Though it is threatened, sometimes violently, by the nastiest people in the world, the concept of “government of the people, by the people, for the people” survives, and it just so happens that this year is expected to see more people voting in elections, in more countries, than ever before.

Partly that is because there are simply more nation states, supranational bodies and devolved administrations than ever, but it is also because free and fair elections (or something approaching that ideal) remain the best form of governance and the soundest long-term foundation for prosperity and peace. It is always worth remembering that wars between fully democratic countries are extremely rare. Can you think of one?

This year, people will be going to the polls everywhere, from Algeria to Tuvalu, with some 2 billion eligible voters (one in four of the world’s population). They will be voting for governments in some of the most troubled and unstable of places – Taiwan, Pakistan and Iran – as well as some reassuringly tranquil ones, such as the Australian Capital Territory (Canberra).

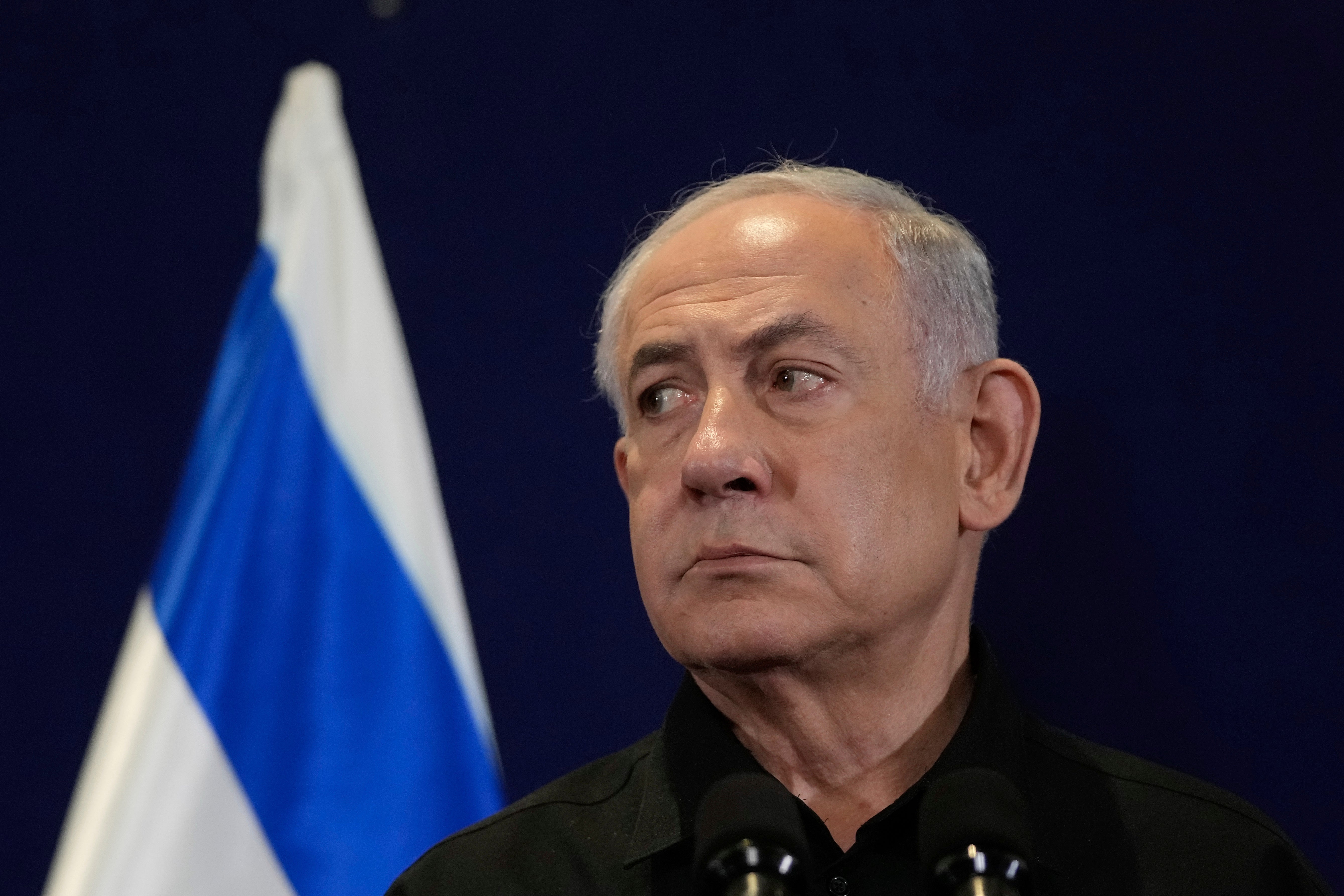

There’s also the prospect of unscheduled and dramatic elections in countries experiencing crisis – of which Israel is the prime example. What if popular discontent with Benjamin Netanyahu’s intelligence failures and questionable conduct of the war with Hamas forced the coalition there to call for fresh elections? It might be one route to peace. It might be the only one.

The most potentially momentous contests will be those in the world’s superpowers, both actual and emerging – the US, Russia, India, and, though it’s not taken that seriously, the European parliament. Why highlight Europe’s very own Tower of Babel? Well, despite its lack of power and its reputation for dullness, the European parliament has influence and can cause trouble for the real seats of power across the continent.

This year will be yet another opportunity for the hard right, and indeed some leftist populists, to be returned in large numbers to the body, with all that this entails for European integration and stability – and especially for the cohesiveness of European foreign and security policy.

None of the major European powers are holding national elections this year, so voters in France, Germany, Italy, Spain and Poland (the countries with the largest populations) will not have the chance to cast their protest votes for Marine Le Pen’s National Rally, the near-fascist Alternative für Deutschland, or the various other ultra-conservative nationalistic groups.

The European parliament elections are conducted under a system of proportional representation, so they may not register the kind of dramatic shift we see under first-past-the-post systems, but they will be a significant indicator of the public mood among the 448 million inhabitants of the EU. Given the likely enhanced presence of Eurosceptic parties and what used to be fringe parties, the European parliament's new balance will raise questions about the very future of the union.

Post-Brexit, Viktor Orban’s Hungary is now the official “awkward squad” within the EU, but the crises Hungary continually stirs up in regard to Ukraine, relations with Russia and refugees are only the most obvious symptom of a wider malaise: that of a political entity never quite able to become a polity.

The question of whether the EU is capable of dealing with the challenges ahead is constantly there behind the petty bickering in Brussels. Migration, the war in Ukraine, the weakened state of the European economy and the strains on the euro will be major issues in the years ahead for all of the EU’s institutions, and the populist nationalists seem bound to gain ground.

One irony of all this is, of course, that if the UK were still in the EU, then Nigel Farage might have found himself at the head of a much more powerful, pan-continental, Eurosceptic nationalist-populist political movement. Instead, he’ll be playing in the much smaller arena of the struggling right in British politics – when the general continental trend seems set to be bucked by the prospective landslide election of a progressive social democratic Labour Party led by a former human rights lawyer. Democratic elections can yield some contrarian results.

As important as they are, the European elections obviously cannot have as much influence globally as those that take place in the United States. At the moment, the contest seems set to be between two elderly figures, while most of the population would probably prefer it if both main parties could come up with younger and less, shall we say, compromised candidates to take the US through turbulent times. It is more than a little perplexing for all concerned, but it seems that the 2024 contest will be a rerun of 2020, and not an especially inspiring one.

The chance to change that might emerge if Donald Trump (who still maintains that he won last time round) is eventually forced to withdraw under the weight of his legal problems, which would make the Republicans opt for someone else and thus trigger a rethink by the Democrats. After all, Joe Biden is there in part because Trump is the only Republican candidate he can beat, and indeed has already beaten, in a presidential contest.

We should be pleased that democracy can spring pleasant surprises of that kind, but also concerned that it can deliver a figure such as Trump, who will undermine the West’s resistance to Vladimir Putin’s imperialism while simultaneously weakening Nato and stirring up trouble with China. Last time round, the US constitution and its delicate system of checks and balances barely survived being roughed up by Trump; strong and venerable as it has traditionally been, there is no God-given reason why democracy in the US should be expected to emerge from another four years of Trumpian abuse, with the second Trump administration determined to take “revenge”.

As flawed as it so often has been, that a democracy of some 1 billion people can function even as it does in India is a thing of wonder. As it happens, India’s prime minister Narendra Modi and his Bharatiya Janata Party are favourites to continue in office, which is good news for Putin, who has successfully courted India as a key strategic ally with historically strong links to Russia and the old Soviet Union.

As for Putin, his largely debased democracy – with little free speech or freedom of expression – will deliver the expected results for the Kremlin. Yet even a sham election such as this will remind the Russian people that there is such a thing as democracy, that change is (theoretically) possible and is in their hands. Some will no doubt wonder where the opposition leader Alexei Navalny is, and how an election can be conducted with him in jail in Siberia.

Much the same can be said about the mostly rigged contests in Iran. They will indeed deliver the desired outlook for the ayatollahs, but with the risk that their grip on power is weakened by the questions that will be raised in March, even in a sham contest, about the future of Iran. The election campaigns, in finer words, could trigger more of the kind of unrest that was seen after the death in suspicious circumstances of a female protester, Mahsa Amini, after her arrest by the morality police in September 2022.

Israel’s war on Hamas, an organisation linked to Tehran, further complicates an already unstable situation there. But if a second Iranian revolution does come, it will probably be encouraging news for the West as well as for the people of Iran. If it meant that Iranian Houthi proxies in Yemen stopped attacking commercial shipping in the Red Sea, it would defuse an incipient economic crisis as well.

Taiwan is another obvious geopolitical flashpoint. The outcome of its presidential elections on 13 January will probably not be a surprise: the elevation of the current vice-president, Lai Ching‑te, to the highest office, and no change in policy on Taiwan’s self-governing, de facto independent status. Less reassuringly, that continues to antagonise China, which maintains that the state broke away from the mainland illegally back in 1949, when the old regime fled there from Mao’s communists.

Few things make the Chinese Politburo more agitated than the Taiwanese making claims about independence, and they enjoy conducting aggressive military exercises in Taiwanese waters and airspace, but there seems little immediate cause to think the elections will provoke a conflict.

Looking ahead, the odd thing about the intensive global round of elections in 2024 is that by the end of the year, and despite the fire and the fury, many of the old faces will still be around. Trump or Biden will be running the US; Modi, the ayatollahs and Putin will still be in situ; and there are plenty of countries where the familiar incumbents, for one reason or another, won’t be troubled by challenges, democratic or otherwise.

In no particular order, these include Emmanuel Macron, Olaf Scholz, Xi Jinping, Lula da Silva, Mohammed bin Salman, Fumio Kishida, Recep Tayyip Erdogan, Benjamin Netanyahu, Justin Trudeau, Giorgia Meloni, Volodymyr Zelensky, Kim Jong-un, Bashar al-Assad, and Anthony Albanese: all will still be very much on the scene in 2024.

The “freshest” face on the world stage after all these elections is most likely to be Keir Starmer. A man of the progressive left in an age threatened by the reactionary right, he will strike a slightly lonely figure when he flies in for the summits and finds himself surrounded by the usual motley crew discussing the same intractable questions.

Elections can help countries, and indeed the wider world, to make progress on old, intractable problems – the climate crisis, slow economic growth, war, pandemics – but we need not imagine that they can make them go away.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments