A researcher at Tulane University’s Brain Institute will receive $2.69 million in federal funding to study how well-timed hormone therapy impacts the aging brain.

The research aims to shed light on whether a short treatment of estrogen at the beginning of menopause may be protective for the brain in later life with fewer risks than the continual use of estrogen.

“There's a lot of research that started in the '80s and '90s to show why ongoing estrogen is a neuroprotective,” said Jill Daniel, the Gary P. Dohanich Professor of Brain Science at Tulane's School of Science and Engineering. “What we’re trying to understand is how a previous exposure to estrogen can have long-term neuroprotective effects.”

Jill Daniel, the Gary P. Dohanich Professor of Brain Science at Tulane University School of Science and Engineering, is investigating whether short-term estrogen use in middle age may lead to better brain aging and memory.

Estrogen’s role

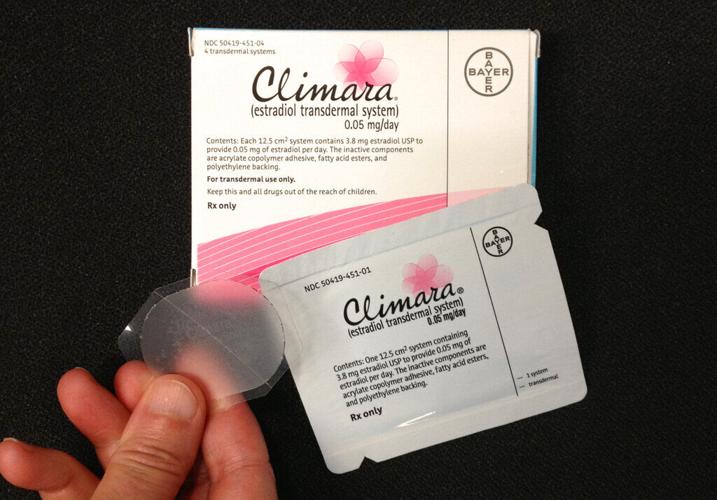

Most of the body’s estrogen is produced by the ovaries. As women approach menopause, defined as 12 months without a period and the end of fertility, hormone levels can dip and spike. The average age of menopause is around 52, though symptoms related to fluctuating hormones can occur between the ages of 40 and 58. Menopausal hormone therapy treats symptoms such as hot flashes, night sweats, sleep disruption and pain during sex.

The brain also produces estrogen, said Daniel, which plays a key role in maintaining neural connections in the hippocampus, the learning and memory center. But research on hormone therapy and cognition later in life has produced contradictory bodies of work, leading to differing understandings among patients and providers of the risks and benefits of the drugs.

Hormone replacement therapy took a big hit in the early 2000s after a large study linked it to increased cardiovascular and cancer risk. But when reexamined, researchers found the study’s design was flawed, said Dr. Jewel Kling, professor of medicine and the assistant director of the Women's Health Center at the Mayo Clinic in Arizona. The average age of women in the Women’s Health Initiative study was 63, even though the average age of menopause is in the early 50s.

“A lot of the headlines were, ‘Hormones are bad,’ ‘Hormones are killing women,’" said Kling. “It really instilled this fear around hormone therapy without recognizing the really nuanced understanding of the relationship of hormone therapy and time of initiation.”

Now, instead of a one-size-fits-all approach, the general consensus is that hormone replacement therapy is lower risk at the beginning of menopause for most women, known as the “critical window hypothesis,” said Kling.

Some data also suggest risk is lower if estrogen is given for a shorter time. The long-term impacts of a few years’ of therapy are still unclear, which is what Daniel's research aims to illuminate.

Window of opportunity

Daniels’ team gave mice the equivalent of three to five years’ of estrogen in midlife, comparing them to mice that got continuous doses of estrogen and mice that got no estrogen.

Mice that got estrogen — whether continuous or short-term — did better on memory tests, such as remembering where food was hidden in a maze. When the researchers looked at their brains, the estrogen groups had better neurotransmitter and receptor levels.

“Our idea is that we could potentially get the neuroprotective effects long-term of estrogen without the putative health risks of staying on (estrogen),” said Daniel.

Daniel’s research could have implications for hormone replacement therapy recommendations.