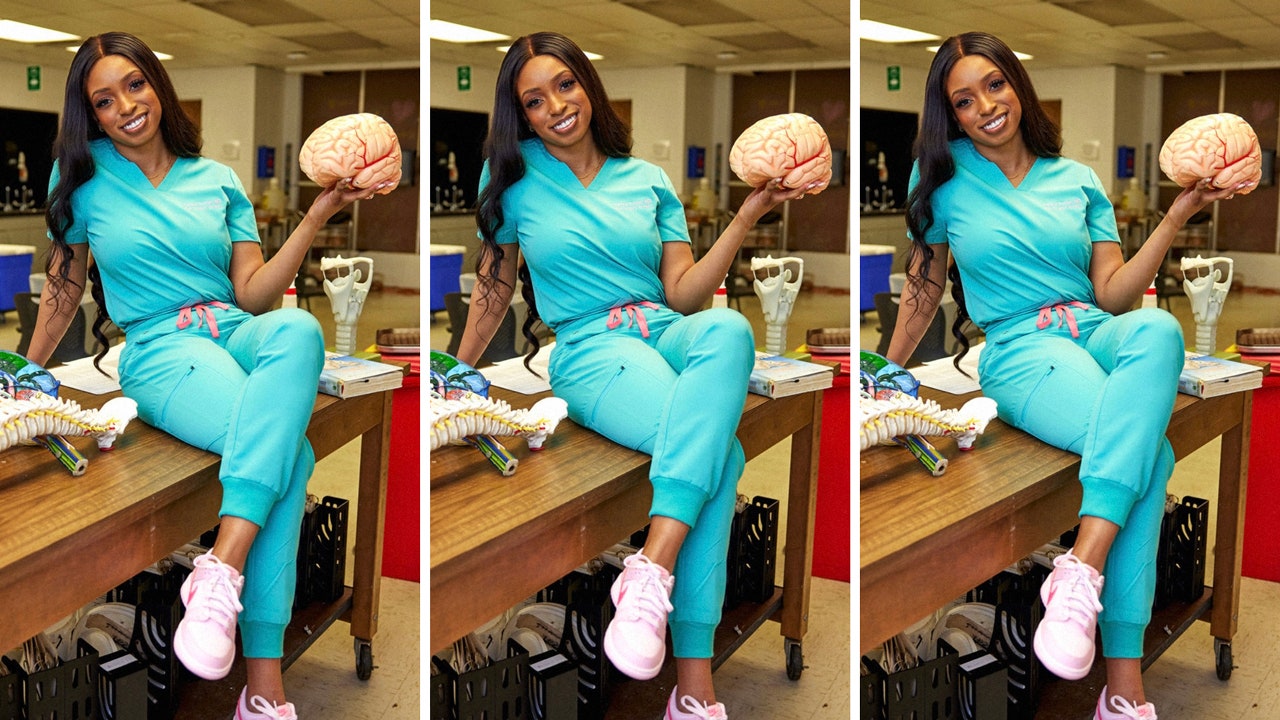

Tamia Potter will soon become the first Black woman neurosurgery resident at Vanderbilt University Medical Center, an institution founded nearly 150 years ago. This achievement is even more remarkable given that, as of 2019, only 0.6% of neurosurgeons in the United States were Black women. Potter is on the brink of breaking a barrier, yet her origin story provides insight into just how much distance a Black woman must travel to succeed.

Potter was born and raised in Crawfordville, Florida, a small town where front doors are rarely locked and neighbors feel like family. And as a child — when she wasn’t outside mud bogging on an ATV or eating fresh food from her grandparent’s farm — she studied the human body. Inspired by her mother, a nurse, Potter developed an early, insatiable curiosity for anatomy and science. During high school, Potter became a nursing assistant and cared for patients in nursing homes suffering from dementia. While in college she was able to observe neurosurgery in the operating room, a moment that truly inspired her path. Potter would go on to complete medical school at Case Western Reserve University with plans to become a neurosurgeon herself.

Teen Vogue explored her journey — full of sacrifice, insecurity, and mentorship — into one of the most competitive and time intensive specialties in medicine.

This conversation has been condensed and lightly edited for clarity.

Teen Vogue: Medicine has over 160 specialties and subspecialities to choose from. What fascinated you about neurosurgery specifically?

Tamia Potter: In high school I became a certified nursing assistant and had my first job at a nursing home. I'd put patients to bed, feed them, bathe them. But they wouldn't remember me. In college at Florida A&M University (FAMU), I started taking anatomy and physiology, and there I learned about Alzheimer's dementia and why my patients didn’t remember me. When I started working at a hospital in Tallahassee, I saw more patients with neurologic issues; they had strokes and brain bleeds. I kept asking the neurosurgeons, “Can you explain to me what’s going on?” And once I was invited into the operating room to see a craniotomy [surgical opening of the skull], I was done.

TV: After high school, it takes approximately 15 years to become a neurosurgeon. Many of these years you are in your 20s. What did you learn about the word ‘sacrifice’?

TP: The youth that you have is precious. But I was not in college on spring break partying heavily. I wanted grades high enough to be competitive for medical school. As an African American person applying to medical school I thought, “How many people in my family have gone on to be a doctor?” Zero. So that meant that I had to go to work. What the average person was doing at 17, I was not. I was working, studying. I sacrificed a lot. I do wish I could go back to college and have the fun times, go stay out late, and do all the things that college kids do. But people hold doctors just to a higher standard, naturally. And that means that some of the things that are acceptable for other people are just viewed in a different light for us.

TV: How did you accept dedicating 15 years of your life to a job?

TP: It's not necessarily years for me. It’s just goals. And the goal in this case — to be a neurosurgeon — requires X, Y, and Z. It just means that every single time I complete a degree, or I complete a period of time, I complete that goal and move onto the next in order to become a neurosurgeon.

TV: As a Black woman, you are entering a space occupied largely by older, white men. In 2018, 65% of neurosurgeons were white men. You are creating a legacy by joining Vanderbilt. How are you preparing yourself?

TP: The best strategy is to focus on yourself. Whenever you go into a space that's unfamiliar, you're more likely to focus on everything around you instead of understanding why you're supposed to be there.

And I can definitely say getting into med school, I thought I was not supposed to be there. I was so intimidated. I thought all these people were smarter than me; they came from Ivy League schools. But then I focused on myself and realized I passed that test, too. I did well with my grades, too. I'm getting good feedback, too. As you continue to do what you came there to do, your work speaks for itself.

TV: You speak a lot about support and mentorship. I’m curious what the difference is between a good mentor and a bad one?

TP: The problem is that most people think that when a mentor has zero feedback for you, that's good. But a mentor might have zero feedback because maybe they didn’t take the time or the energy to examine your work. I used to be really hurt when I'd give my faculty papers and they'd come back with serious edits. I thought, “These people hate everything that I say.” But then I realized that I needed those edits.

A bad mentor will avoid you and dismiss a lot of your concerns. Some will exploit you — they may try to get you to do work for them. Or they may promise you things that are just not even possible.

TV: How do you maintain such a clear focus on the goal of being a neurosurgeon?

TP: I've strategically tried to make sure that all the other tasks in my life revolve around my one goal. I have three jobs currently while in medical school. I have to support myself financially. All my jobs — volunteering, tutoring, or teaching — are very similar in nature and they are goal oriented towards neurosurgery.

TV: You went to an HBCU for college. What was the strongest skill you learned from attending FAMU?

TP: I learned how to communicate and how to network. At FAMU, you know your professors. These professors pray for you, they bring food to school, they invite you to their house. These professors are your family. Going to an HBCU feels like you're just at a very large family reunion and you're learning at the same time. I was never afraid to ask a question. I was never afraid to ask for help. And I think I brought that with me to medical school. No matter where I’m going, I know that I can ask the people around me for support when I need it.

Stay up-to-date with the politics team. Sign up for the Teen Vogue Take