When the New England Patriots upset the St. Louis Rams in Tom Brady’s first Super Bowl, way back in 2002, Brady was throwing passes to Kevin Faulk, Troy Brown and David Patten. By 2008, he was throwing to the greatest wide receiver of all time, backed by a deep, talented receiving corps. Once Randy Moss left town, the Pats retooled with perhaps the best tight end in NFL history — and again once that tight end was repeatedly lost to injury. These were all very different players with very different strengths, but the Patriots found success with all of them.

One of the more remarkable things about Brady appearing in his seventh Super Bowl on Sunday against the Atlanta Falcons at age 39 is how many different styles of offense he has found success in. It’s rare enough to find a quarterback who can make all of the throws, let alone one who can do it to so many different players with so many different game plans.

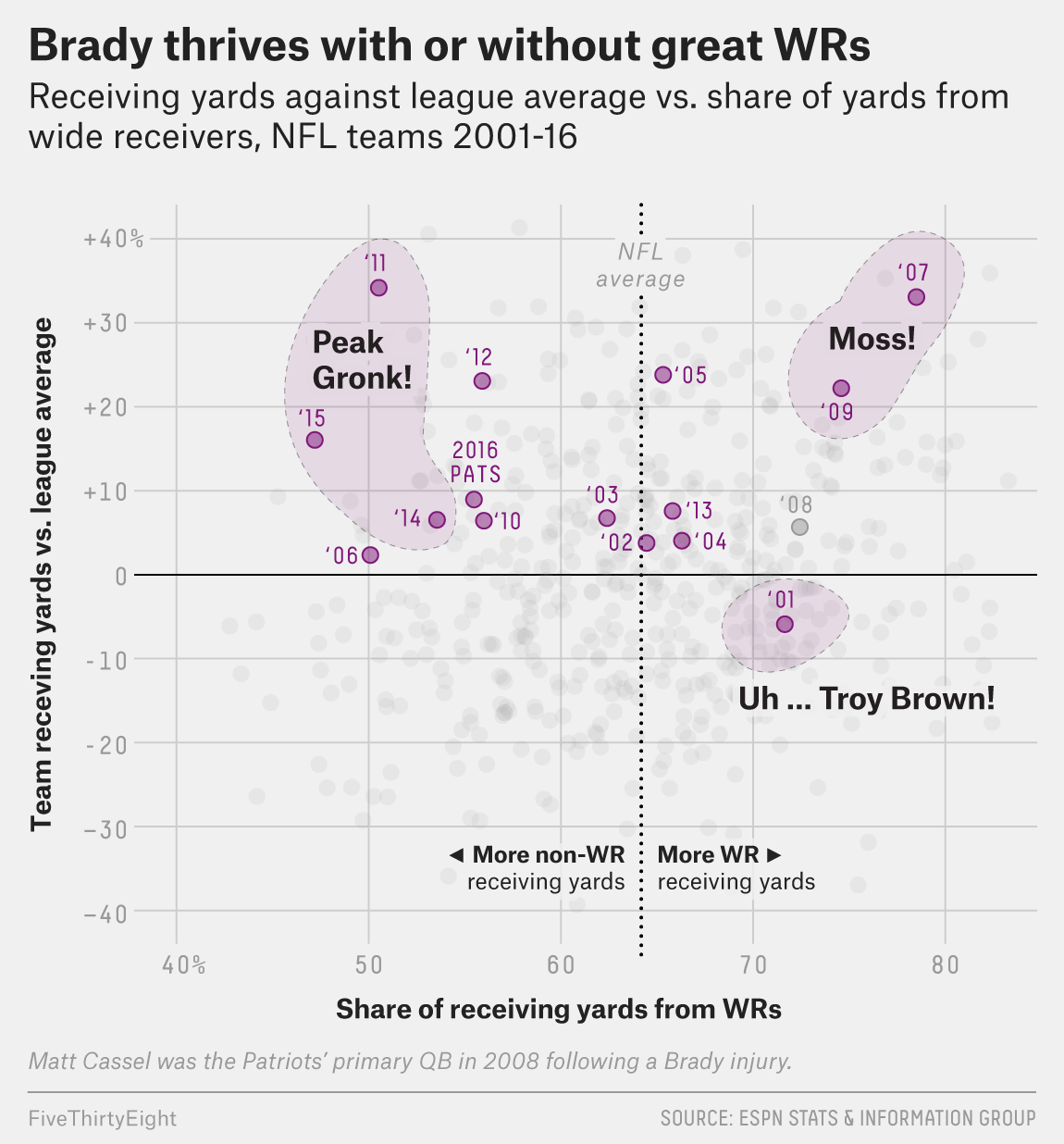

Brady isn’t going to beat anyone with his legs (although he’s an effective sneaker), but the Patriots are unmatched in tweaking their offensive strategy for the personnel on hand. New England has had great offensive seasons in which over 70 percent of passing yards went to wide receivers, a high rate for the NFL. The Patriots have also had great seasons when WRs caught half of their yards or less, a rarity in the league.

The 2016 Pats are light on wide receivers, although not exceptionally so for a Brady-led team. Julian Edelman topped 1,000 yards, and Chris Hogan established himself as a useful second receiver, but Danny Amendola mostly disappeared (putting up 243 yards in 12 games), and Malcolm Mitchell wasn’t exactly devastating. Meanwhile, tight ends Martellus Bennett and Rob Gronkowski (in eight games) combined for 1,241 yards, while running back James White chipped in another 551 in receiving.

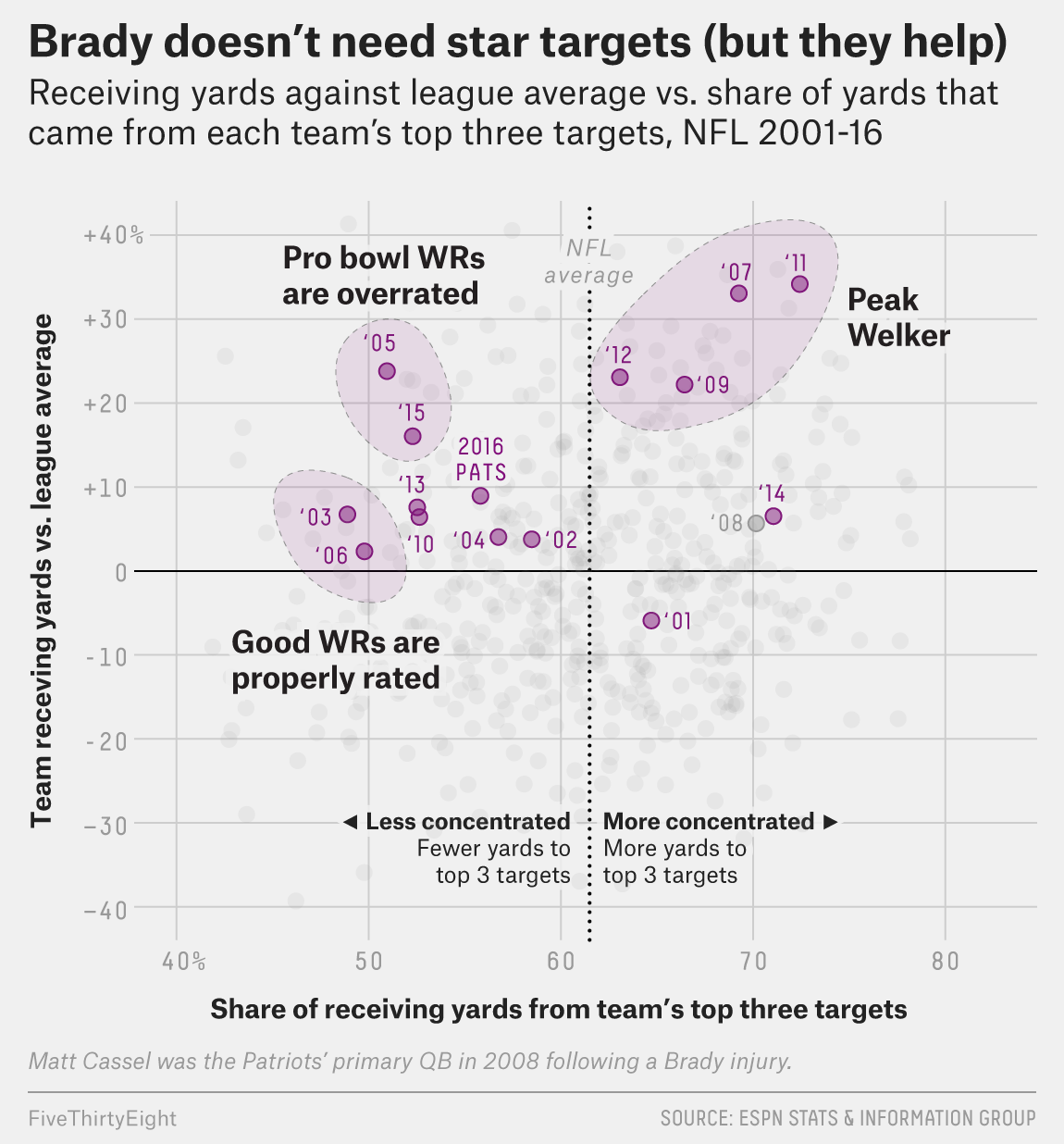

But, thanks in part to the Patriots, these positional distinctions don’t mean as much as they used to. Gronk isn’t a WR like Randy Moss was, but he is still more or less used as a receiver (a distinction that is, as Seahawks pass-catcher Jimmy Graham found, worth a lot of money in the pay scale). Perhaps a better way of looking at Brady’s versatility is how he does in the presence or absence of top targets. And while the Pats’ best seasons have come with major weapons at their disposal, they do just fine without them, thank you.

Five-time Pro Bowl wide receiver Wes Welker was greatly responsible for some of the Patriots’ most concentrated (and successful) passing seasons, eating up yards alongside Moss and Gronkowski. During his four best years, the Patriots were truly a star-driven passing offense, with fourth and fifth options like Jabar Gaffney and Danny Woodhead making a comparatively small impact in the passing game. In 2011, New England’s most top-heavy season of the Brady era, Welker, Gronkowski and Aaron Hernandez accounted for 33 of Brady’s 39 receiving touchdowns and over 70 percent of the team’s receiving yards.

But the Pats don’t need stars in order to succeed. In 2005, Deion Branch, David Givens and Troy Brown caught just a little over 50 percent of the Pats’ receiving yards, with Ben Watson, Tim Dwight and Kevin Faulk adding contributions. An injury to Edelman in 2015 led to a similar situation – Gronk was the only player to crack 700 receiving yards, but eight players had at least 250. Of course, it helps to have some talent — the 2006 Patriots didn’t get much happening in their passing game with Reche Caldwell as WR1.

That success with diverse sets of receivers has also come with diverse sets of game plans. Unlike, say, Packers quarterback Aaron Rodgers rolling left or Cardinals signal-caller Carson Palmer gunning the deep ball, conventional wisdom says that Brady’s game morphs to fit his personnel.

One way we can test whether that’s true is to look at whether the things Brady was known for early in his career have continued to be central to his game as his career has progressed. At one point, the nearest thing he had to a specialty (besides those QB sneaks) was the play-action pass. Play-action is an effective part of any offense, and certain quarterbacks tend to rely on it more than others. But while Brady mastered it alongside future Hall of Famers Peyton Manning and Drew Brees, it has drifted in and out of his game over the years.

ESPN’s more advanced passing data only goes back as far as 2006, after Brady had already established himself as a top quarterback — but a year before Moss and Welker showed up and the Pats began breaking passing records. Even picking up then, we can see drastic shifts in how often the Pats have gone to the run fake and how much of the passing offense it has made up.

By 2010 — a down year by New England’s standards but the first year of the Pats’ experiment with two-tight end jumbo packages — 31 percent of Brady’s passing yards were coming on play-action passes; rookies Gronkowski and Hernandez helped the Patriots to the highest rate in the league, a stark contrast from 2006 when Brady ranked 29th out of 32 qualified passers.

The unpredictability goes for other supposed Brady calling cards, like consistent yards after the catch. Brady typically rates among the league leaders in YAC per completion, but he dipped to 24th out of 33 qualified passers in 2014, a season in which the Pats went 12-4 and won the Super Bowl.

There’s no telling how long Brady will keep making it deep into the postseason, but just as compelling as wondering how long the old man can keep this up is waiting to see what sort of offense he’ll bring with him if he does.