Lowell Hawthorne so loved the American dream that when he finally made it, he commissioned an architect to design his Westchester home to resemble the White House.

The multimillion-dollar home with a four-columned portico was one of Hawthorne’s many symbols of success. Known as the Jamaican patty king, he had a Bentley parked in his garage and in his sprawling back yard, a replica of the babbling brook that ran behind his rural childhood home.

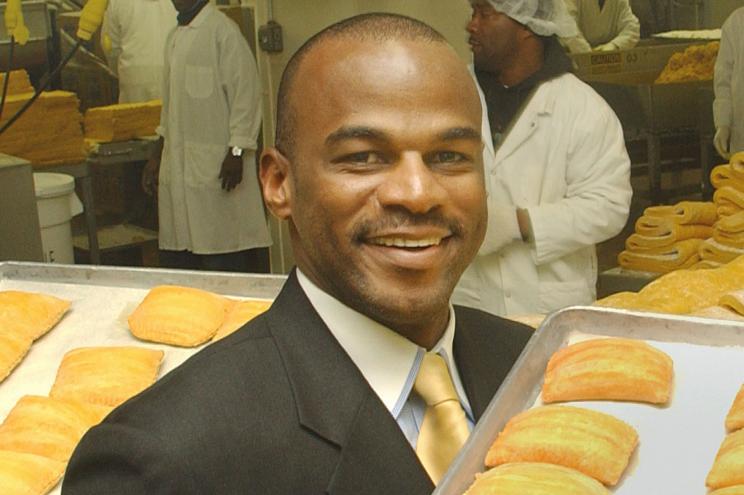

Well known in New York’s Caribbean community as a generous philanthropist and deeply religious man, the CEO and founder of Golden Krust Caribbean Bakery & Grill seemed to have it all. And the future looked bright: His company, which employs 1,800 people, had embarked upon a multimillion-dollar expansion into the Canadian market and had just opened a plant in Rockland County to meet heightened demand for the company’s crusty breads and signature beef patties. On the home front, the 57-year-old had just welcomed his first grandchild. He was “super excited,” visiting the infant almost daily, said a longtime family friend.

For all these reasons, Hawthorne’s friends are hard pressed to explain why this married father of four with a net worth of nearly $500 million drove his silver Tesla 85D to his Bronx factory on Dec. 2, entered the building, raged at two employees and sat behind his desk, where he shot himself in the head — his bloody end captured on one of the building’s surveillance cameras.

“He was the most impressive person I knew. He was one of the most self-actualized people I have ever met. He was a self-made millionaire, but he was also focused, erudite and very respectful,” said Robert Gretczko, an ad exec who knew Hawthorne for more than two decades. “I was in disbelief, and I thought I was getting pranked when a friend called me with the news.”

Lowell Hawhtorne was born May 1, 1960, in Border, a tiny hamlet in rural Jamaica with no running water. He was the sixth of Mavis and Ephraim Hawthorne’s 11 children. The family had modest means. Ephraim was the local baker, and the family owned the only TV set for miles around. In his 2012 memoir, “The Baker’s Son: My Life in Business,” Hawthorne described how neighbors would come by to watch television, “camping out on our front porch and craning their necks for a glimpse of the action.”

Hawthorne developed an entrepreneurial spirit while still at Oberlin HS in Jamaica’s St. Andrew West Rural district and would go on to operate a local minibus that ferried rural passengers and rent out a stereo he acquired for parties and events to neighboring villages.

But he longed for something more, and on May 2, 1981 — a day after his 21st birthday — he landed at JFK Airport, leaving behind a pregnant girlfriend. He took up residence in the city with his older sister, Lauris, a health-care worker who lived in The Bronx.

His first job was folding shirts as an inventory clerk at Abraham & Straus, a now-defunct men’s store in Brooklyn — a task he claimed he could never master. Hawthorne left after just three weeks and soon landed a job with the NYPD unloading supplies. At night, he attended business and accounting classes at CUNY, but did not get a BA until last year, when he earned a bachelor’s degree in business administration from Lehman College.

“I took advantage of the opportunities that came my way,” he wrote in “The Baker’s Son.”

In addition to rising through the administrative ranks at the NYPD, where he eventually became an accountant handling police pensions, he also started his own accounting business from home and completed the tax returns of many of his co-workers and friends on the force.

In addition to rising through the administrative ranks at the NYPD, where he eventually became an accountant handling police pensions, he also started his own accounting business from home and completed the tax returns of many of his co-workers and friends on the force.

In 1983, he fell head over heels for Lorna Roach, now 55, at a party in the city. “My gaze was fixed on her high cheekbones and striking beauty,” he writes. “We struck up a conversation, and from that moment, I knew fate had brought us together for a reason.”

The couple soon married, and Lorna gave birth to three children. Hawthorne’s first son, Haywood, born to his ex-girlfriend in Jamaica shortly after he left the island, would eventually join the family in New York.

“I wanted to make sure I could give them a life I never had,” Hawthorne said in an episode of the reality TV show “Undercover Boss,” which featured Golden Krust in an episode last year.

In 1989, Hawthorne left what had become a secure job with the NYPD to start Golden Krust with his siblings. He said he got the idea when he watched his sisters baking and selling traditional Jamaican Easter buns to friends and work colleagues. The family managed to scrape together $107,000 to begin the bakery that would first produce Jamaican sweet buns, fruitcakes and other delicacies. Patties would be added later.

“Many of the professionals I worked with at the NYPD thought it was a bad idea to give up a good city job to start a bakery business,” Hawthorne wrote. “I saw the enterprise as an opportunity to make millions.”

Golden Krust took off almost instantly. Within a few years, Hawthorne employed 44 family members, and his wife became the company’s head of human resources.

“Our first set of employees was me, my siblings and close relatives who had worked at my parents’ bakery in Jamaica,” he wrote. “After 20 years in business, nearly everyone who started with us is not only still actively engaged in the business but has grown with us.”

The family was so grateful to Hawthorne that on his 50th birthday, his siblings chipped in to buy him a Bentley, Gretczko said.

“He kept it in the garage and would only take it for a ride with his wife on a few special occasions,” Gretczko told The Post. “They felt the car was too flashy for them.”

In the early days, Golden Krust first set up bakery operations at an industrial building on Gun Hill Road in The Bronx, and Hawthorne soon found himself paying weekly protection money to local mob bosses who controlled the commercial garbage collection in the neighborhood.

When Hawthorne tried to break out of what he called “the devil’s deal” with the mob — paying $1,500 a week for garbage pickup — he found hundreds of rotting fish heads along the bakery’s stretch of Gun Hill Road, he wrote in his memoir.

‘I’m as competitive as the next CEO, but I differ from most in one significant way: I would gladly trade the entire business for the life or the restored health of any family member.’

- Lowell Hawthorne

Hawthorne remained steadfast in his refusal to pay the wiseguys and found another sanitation company that charged him a fraction of the cost to remove the company’s trash. In his book, he describes how the mobsters stopped harassing his company after he involved some of his former colleagues in the NYPD.

Golden Krust flourished, with dozens of successful franchises opening up in Caribbean neighborhoods throughout the city.

And Hawthorne became a respected leader of the Jamaican community, donating thousands of dollars to his native country during times of crisis and distributing hundreds of scholarships to both Jamaican and American students through his family foundation, named in honor of his parents. Every June, Golden Krust donates 100 percent from the sale of all “crusts” (bread without filling) toward scholarships. He has established endowments at Bronx Community College and the University of the West Indies in Jamaica, where he was also the chairman of the school’s American charitable foundation.

He also built a sprawling mansion in Jamaica and invited extended family members to vacation there, a friend said. He became an avid tennis player.

despite his success, Hawthorne confessed in his memoir that he sometimes found it difficult to cope, especially when faced with personal tragedy.

“I’m as competitive as the next CEO, but I differ from most in one significant way: I would gladly trade the entire business for the life or the restored health of any family member,” he wrote. “On a couple of occasions, I almost did.”

After his mother died of cancer in 1994, Hawthorne said, he was so heartbroken that he simply stopped answering his mail and lost opportunities to expand the company. He missed out on contracts to bake 50,000 halal patties a month for the New York state prison system, he said.

Ten years later, when his second son, Omar, was hit in a near-fatal car accident he contemplated selling the business.

“That was the only time I saw him really shaken up, but he overcame it,” said Louis Grant, executive vice president of Irie Jam Radio and a Golden Krust franchise owner who was friends with Hawthorne.

Two years later, in 2006, the death of his father, whom he considered a confidant and role model, struck another huge blow.

“My adviser and sounding board, my foundation was no more,” he said. “It felt as if my gut had been ripped out.”

Religion helped him survive. Hawthorne, who had grown up in an evangelical family, became even more active in his church, the First Community Church of the Nazarene in Valhalla, Westchester County, after his parents’ deaths. He was baptized in January 2009, said his pastor, Leroy Richards.

Still, there were demons plaguing Hawthorne. The CEO’s business was reportedly being investigated by the IRS, and he owed millions in back taxes. Hawthorne and his brother Milton were named in a class-action lawsuit last August alleging that they cheated more than 100 workers at the company’s Bronx bakery out of overtime pay. The court action is ongoing. On Thursday, two workers in The Bronx and Brooklyn filed a second suit in Manhattan, alleging that they were denied overtime, had to pay out of their own pocket to clean their uniforms and were denied employee tips.

“He might have realized that his empire might collapse,” Gretczko said.

In 2010, Hawthorne acquired a gun permit, public records show. Seven years later, he walked into a Golden Krust factory and ended his life with a well-aimed single shot to the head, leaving a suicide note apologizing to his family for his actions, according to reports. Minutes after the police arrived, family and friends raced to the Bronx bakery, where they cried and comforted one another on the desolate stretch of Park Avenue where Hawthorne’s American dream first started its incredible story.

In the wake of his death, friends told The Post that Milton is poised to take over the Jamaican food empire, which includes 120 Golden Krust franchises across the country and monthly sales of millions of beef patties to schools, prisons, the military and more than 20,000 supermarkets. But with the company dogged with financial troubles and now reeling from the loss of its charismatic leader, it’s hard to imagine where it goes from here.

Asked if he knew why Hawthorne committed suicide just weeks before Christmas, even with financial troubles, his pastor seemed at a loss. “He was consistently a pleasant, ebullient and outgoing person,” Richards said. “He was a source of great inspiration and people as far away as Canada, the UK and Jamaica are now grieving alongside his family.”

Thousands are expected to attend Hawthorne’s funeral at the sprawling Christian Cultural Center campus in Brooklyn on Dec. 19. It was decided early on that the family church would be too small to handle the crowds.

“He’s the Usain Bolt of business for Jamaica,” Richards said. “For each Jamaican immigrant, Lowell Hawthorne is me, he’s you. He was the soul of Jamaica, the son of our soil, and all of our struggles were identified with him.”