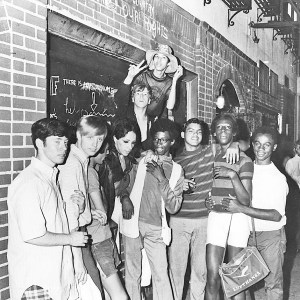

How do we recall an event for which only the vaguest of records exists, with most of the central actors dead and gone? The Stonewall riots of 1969, which gave rise to the modern LGBTQ rights movement, rest on one unequivocal historical fact: On the night of June 28, 1969, police raided the Stonewall Inn, a gay bar in Greenwich Village, sparking protests that have been commemorated in New York every year since. But other historic details remain murky.

History exists, of course, because someone wrote it down — usually a straight man. The reason there are so few stories about LGBTQ people in history books is not because they don’t exist; they simply weren’t recorded. To do so would have imperiled lives. The stories instead went underground, or worse, were left untold. It’s only now that some of those narratives are being reclaimed.

Indeed, Stonewall took place when the mainstream media was either hostile or indifferent to LGBTQ life, so the published record is scant. It may be hard to imagine in our era of social media saturation, but at the time there was almost no way for individuals to capture a spontaneous event as it unfurled. Beyond those factors, much of the night’s significance emerged only in hindsight.

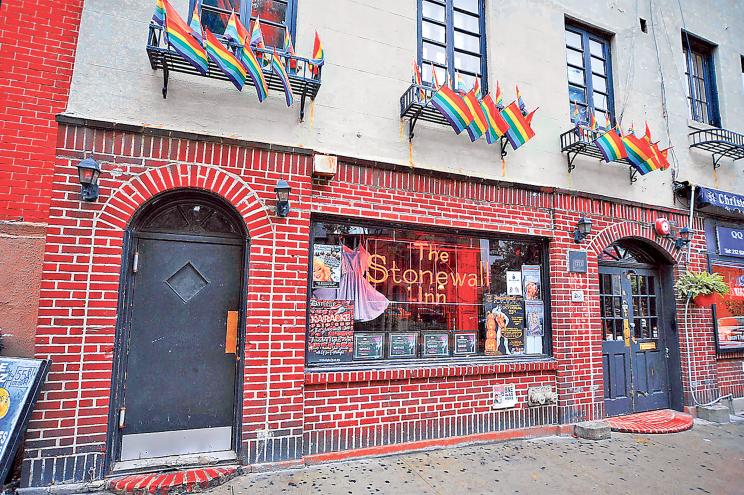

Raids on gay bars were hardly uncommon in the 1960s, and Stonewall was not the first example of backlash. A 1967 police raid on a Los Angeles bar, the Black Cat, unleashed similar demonstrations. In 1966, gay men in New York protested the State Liquor Authority’s policy of routinely revoking the licenses of bars that served gay men and lesbians by staging a “sip-in.” What was different about Stonewall was that it galvanized tribute protests a month later — the first manifestations of Gay Pride — which continued each year thereafter. And rightly or not, the unassuming bar is now seen as the cradle of gay liberation.

In the absence of verifiable stories, Stonewall has become a canvas on which to project the stories we want to tell. Those stories morph as wider society changes. In recent years, it’s become axiomatic to credit the uprising to transgender patrons such as Marsha P. Johnson and Sylvia Rivera. A 2015 film about the riots by Roland Emmerich, meanwhile, was widely condemned as being out of touch for depicting a white gay guy throwing the first brick, though in fact, no one knows who hurled that first brick, or even whether a brick was thrown. As it happens, Johnson turned up after the riots had started, and Rivera herself debunked the notion that the bar was popular with transgender people and drag queens. “The Stonewall wasn’t a bar for drag queens,” she told the journalist Eric Marcus in 1989. “Everybody keeps saying it was…No, only a certain amount of drag queens were allowed into the Stonewall at that time.”

While specific details from the original uprising remain the subject of debate, the events are widely credited with launching the modern LGBTQ rights movement.

Of course, transgender people were part of the riots, Rivera among them, but so were gay men, so were lesbians. Bickering over who should take credit is a symptom of these bifurcated times. The real reason people like Rivera and Johnson matter does not rest on whether they threw an actual brick at Stonewall, or whether it was the first, second, third or 10th brick. They matter because they’ve been throwing bricks throughout history, metaphorical and otherwise.

People like Rivera and Johnson never had the luxury of passing as straight, as so many gay men and women have done — mindful of the long shadow of Oscar Wilde. It’s why inns like Stonewall kept their numbers to a minimum — they represented what the other patrons were trying to disguise. Unable or unwilling to hide, they learned to represent instead.

“We are the ones that went out there and we didn’t take no s–t from them,” Rivera told Marcus. “We didn’t have nothing to lose.”

As a set of facts, Stonewall is nebulous and shrouded in counter-narratives. But as a symbol, it is potent and simple: It announced that the gay and transgender community would no longer be pushed around.

Five decades from that seminal date, the tide of progress that once seemed unstoppable now seems to falter and flag. After being accepted into the military under Obama-era policy, transgender service members find themselves banned again by a seemingly punitive administration. The Supreme Court, with its 5-4 conservative majority, is due to determine whether job discrimination laws should extend to sexual orientation and gender identity. It’s been over 50 years since such matters were settled when it came to questions of race, color, religion, sex and national origin. That such a question is up for discussion in the wake of marriage is a warning that progress can’t be taken for granted.

The wellspring for the riots on June 28, 1969, was anger at years of harassment, but it was anger allied with purpose. The purpose was full equality in the eyes of law. When the LGBTQ community marches on June 29 this year, it will celebrate the distance traveled while also reflecting on the distance still to go.