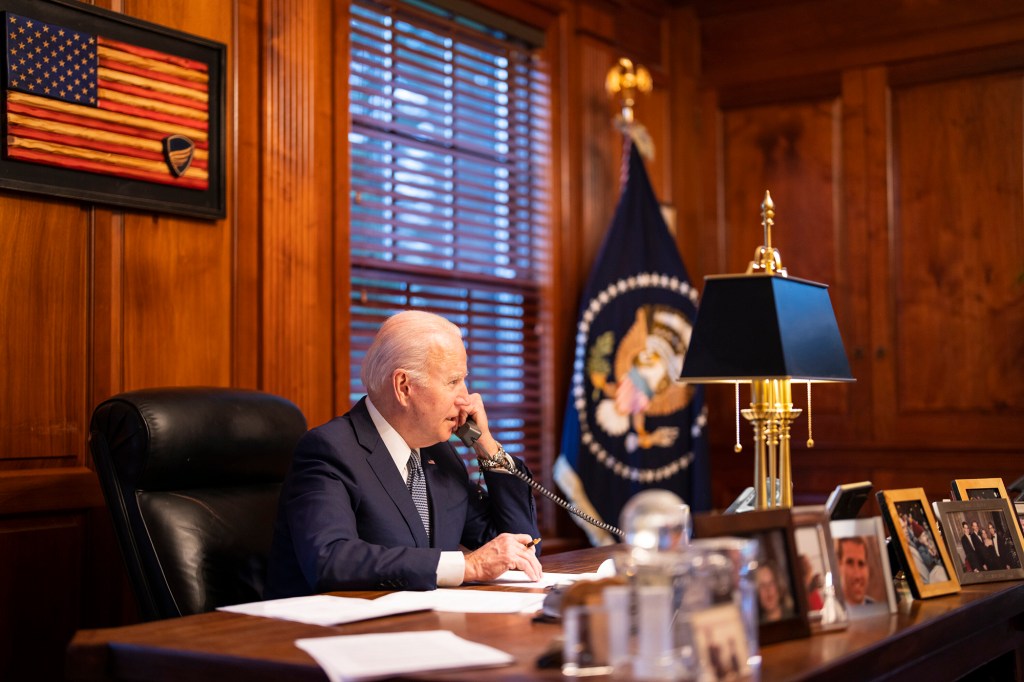

Putin got just what he wanted from his phone call with Biden

Why are Vladimir Putin and Joe Biden now regular phone buddies?

Putin initiated their Thursday call, the latest step in his new political and military offensive designed to break the stalemate in Moscow’s almost-eight-year war against Ukraine. Moscow “annexed” Crimea and began a not-quite-covert hybrid war in Ukraine’s east to coerce Kiev to back off its Western-oriented foreign policy, in particular its quest to join NATO and the European Union. But the Kremlin is no closer to its goals today than it was in April 2014, when it launched the war in Donbas.

So Putin decided to up the ante by placing more than 100,000 well-equipped troops on or near his border with Ukraine and threatening military action if Ukraine were to join NATO or even host a NATO base or advanced NATO-supplied weapons systems. The point is to intimidate Kiev into making concessions in the Minsk negotiations on ending the war in Donbas — or Washington and Brussels into weakening support for Ukraine. This play is clearly a test of the still-young Biden administration and, to a lesser extent, the new German government under Chancellor Olaf Scholz.

And the Dec. 30 call aimed to test and weaken US resolve.

The slim White House and Kremlin readouts on the call provide little beyond the talking points both sides have been using for the last three weeks. Biden repeats that America will respond with strong steps if Moscow launches a new invasion but is also ready for talks. The Kremlin readout notes that America said it was ready to impose sanctions and would not deploy “offensive weapons” in Ukraine (which was not news) but that the talks set the right tone for the negotiations to come.

The actual conversation likely broached the more difficult issues on which there is disagreement; but neither side wants to highlight that — and Washington didn’t want to displease Moscow.

Putin’s threat has certainly gotten Washington’s attention — for over two months it’s been warning that Moscow might launch a major conventional offensive against Ukraine. And Kremlin efforts have convinced some analysts that an offensive is inevitable.

Putin’s problem is that the Biden administration not just sounded the alarm but rolled out a package of measures designed to deter a Russian escalation. It warned that such an offensive would prompt new, punishing economic sanctions against Russia and the Russian elite, additional US weapons supplies to Ukraine and a strengthening of NATO’s defenses in the countries bordering Russia. Washington also rallied NATO and major European countries behind these measures.

But Putin also has an edge. While Team Biden recognizes that a full-scale Russian invasion of Ukraine must be prevented, it is also eager to establish a “stable and predictable” relationship with Moscow despite its ongoing provocations. That was evident in Washington’s weak reaction to continuous Russian cyberattacks in the spring and fall that contravened the red lines Biden laid down at his Geneva summit with Putin and in a subsequent July phone call.

This impulse explains why, right after the administration stood down the Russian military buildup along Ukraine’s borders in April, it began a dialogue with Moscow that led to the June Geneva summit and quickly followed its strong warnings to Moscow this fall with a phone call between national-security adviser Jake Sullivan and his Russian counterpart, Nikolai Patrushev, that led to December’s virtual summit.

Putin sees and takes advantage of this impulse. The spring Russian buildup ended quickly, and Moscow paid no price for that provocation. So it’s no surprise that the current buildup is larger and more threatening than the spring dress rehearsal and has already lasted 2 1/2 months. These summits are a gift to Putin, who relishes being on the big stage with America, but more important, they are an opportunity for him to gauge Biden’s willingness to stand up to Kremlin aggression and to push for Washington concessions.

Putin successfully used the Dec. 7 virtual summit to extract Biden’s agreement to US-Russian talks on “European security.” And a week after the summit, Moscow handed Team Biden two draft treaties, one for America and the other for NATO, that included unacceptable demands limiting NATO membership and Ukraine’s sovereign right to receive weapons from NATO nations. Meanwhile, Moscow kept tensions at high pitch by continuing the border buildup and having its defense minister issue a statement saying US contractors were introducing chemical weapons into Ukraine, a possible pretext for a conventional military strike.

But the Kremlin noticed that as late as Dec. 23, White House spokeswoman Jen Psaki was saying no discussion date had been set. It’s hardly a coincidence that Team Biden agreed Dec. 28 to talks with Russia starting Jan. 10 and announced Dec. 29 that the two presidents would speak the next day at Putin’s request. In a sense, the requested phone call achieved its purpose with the Dec. 28 scheduling.

Team Biden is hoping that Moscow’s relatively positive description of the talks means that the crisis has crested and it can look forward to Russian troops moving away from the border. Putin decided to reduce the pressure in this phone call and await the results of the first week of negotiations. It is unlikely that there will be a significant Russian de-escalation before that.

John Herbst is director of the Atlantic Council’s Eurasia Center and a former US ambassador to Ukraine.