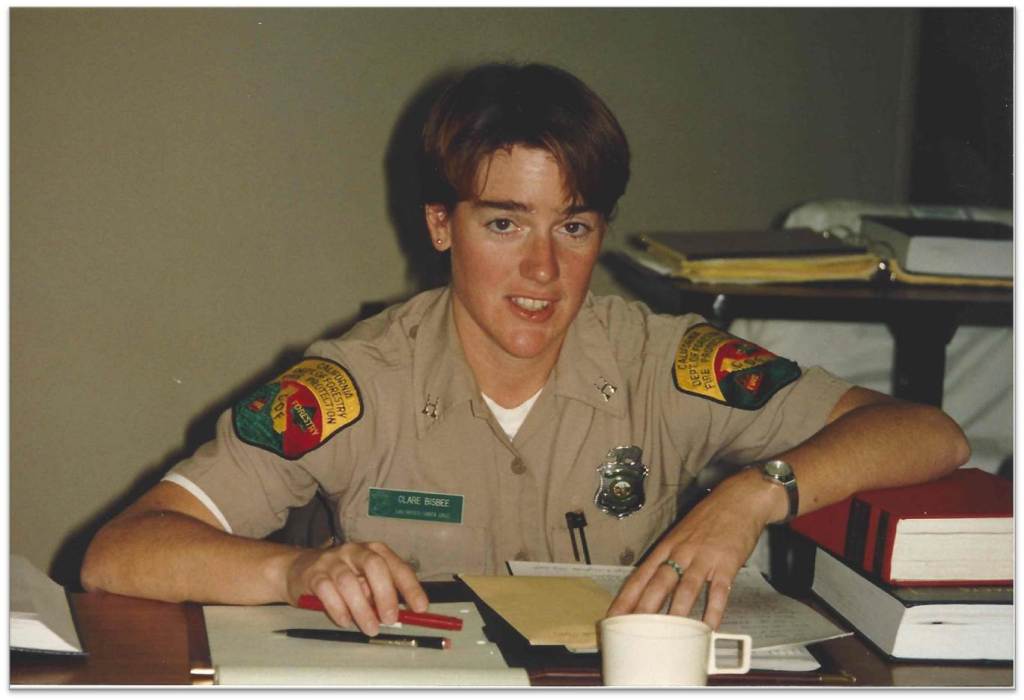

In 1982, 17-year-old Clare Frank was legally emancipated from her parents, moved into an illegally converted garage apartment in Santa Cruz, and became a firefighter in Northern California.

Frank graduated at the top of her training class.

Still, the scrawny, 5-foot-2 teen was too young to join the service; she left her date of birth blank on her paperwork and prayed no one would notice she wasn’t yet 18.

They didn’t, but she still had to prove her mettle.

“I haven’t had a girl I haven’t fired,” her gruff new boss told her the day they met.

She swallowed, looked him in the eye and said, “I hope to change that.”

Frank not only survived that first rookie fire season — running toward the wild blazes that regularly engulf California in flames from summer to late fall — she lasted three thrilling, terrifying decades.

She retired in 2015, the state of California’s first and only female chief of Fire Protection, as record-setting fires ignited her home state year after year.

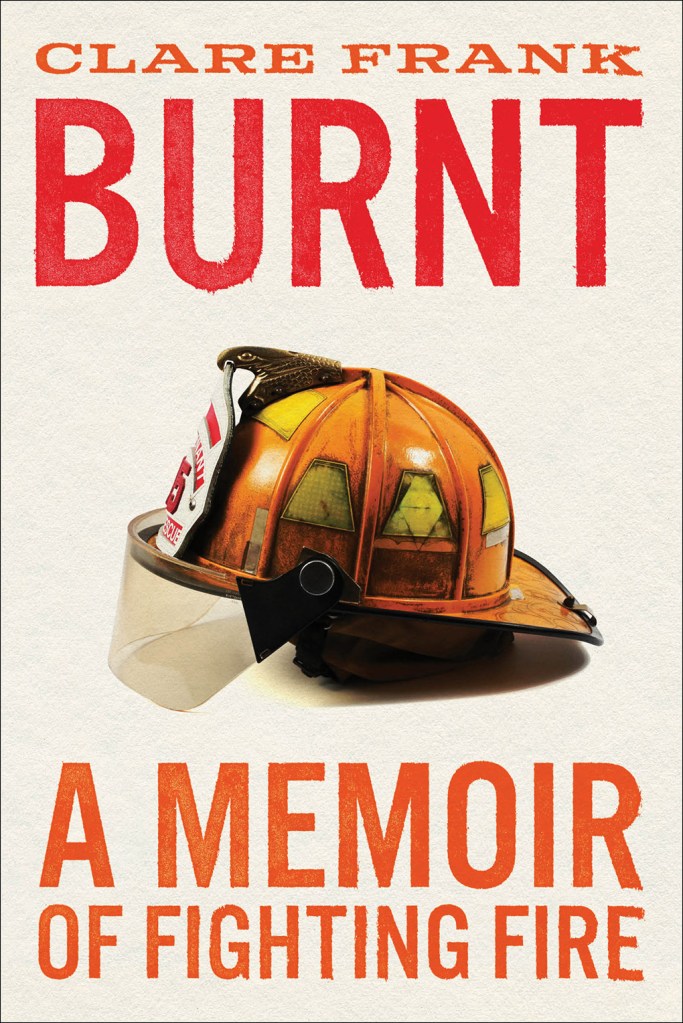

Her new memoir, “Burnt” (Harry N. Abrams), chronicles her trailblazing bravery.

“Failure in this realm would splatter on other females who wanted a life filled with dirt and danger.”

Clare Frank, on being an industry trailblazer

Frank writes that she had no choice but to succeed — for her beloved West Coast, for the planet and for future generations of girls drawn, like her, to the dangerous allure of fire.

“Failure in this realm,” she writes, “would splatter on other females who wanted a life filled with dirt and danger.”

Frank was destined for a life of fire. (An “Indian pundit” told her so when analyzing her birth chart.)

When she was 4, a wildfire came within a mile of her family’s home in LA. Her parents — utterly unfazed — gathered Frank and her five older siblings in the backyard “to watch the show as [the fire] threw ash our way.”

She was captivated.

“Nothing about fire — its power, heat or unpredictable movement — inspired fright in me.”

Frank had a peripatetic childhood.

She went to 16 different schools by the time she was in 10th grade.

When her “quixotic” father announced they were moving again, Frank put her foot down. She convinced her parents to emancipate her; California law allows kids as young as 14 to be emancipated, as long as they have a legal source of income and are living apart from their parents with their consent.

She then followed her brother Mark’s footsteps to firefighter boot camp.

After smothering her first forest fire, she sat exhausted, dripping in sweat, her feet covered in blisters, but elated. “I felt whole,” she writes.

Frank jumped from station to station, extinguishing flames up and down the Golden State.

She made her way up the ladder too, from rookie to engineer to captain and beyond.

She battled sexual predators and sexist pigs; braved the communal shower (she was relieved that the dudes — too tired — didn’t even seem to notice a member of the opposite sex in their midst); buried dozens of mentors and peers; delivered a baby while in the line of fire; witnessed mangled bodies in car crashes; blew black snot out of her nose; damaged her lungs.

In 1997, she suffered an injury that landed her in an emergency room, where a doctor removed all her toenails.

She was told she couldn’t put on a pair of fire boots for five years.

So Frank — who never even completed a bachelor’s degree — went to law school and became an attorney instead.

But after 9/11 Frank — now married, living in San Jose — felt the lure of being a first responder again.

She got cleared for duty, quit her cushy job and suited back up.

“I loved being back in uniform, free to cuss at my coworkers,” she writes of her return.

“It was the grind I’d missed as a lawyer. I smelled bad, had smoke-filled lungs . . . and achieved new levels of fatigue.” At one point she got three hours of sleep over four days. She also developed adult-onset asthma. “I was thrilled.”

By the end of her tenure, Frank was not only fighting fires, she was trying to prevent them as California rapidly became an inferno, its blazes growing more frequent and intense.

After her retirement, she moved to the Sierra Mountains with her husband and got an MFA in creative writing.

Then in 2021, she found herself trying to escape a fire rather than running toward one.

In a twist of fate, a wildfire was blazing its way through their region, heading directly to their home in Nevada.

“We weren’t in a fire-prone area, yet Mother Nature had found a way to bring fire to us,” she writes.

Their home didn’t end up incinerated.

Yet Frank did not feel much relief.

“As a society, we are accepting the accelerating cycle of fire,” she writes. “But we can and should do better.”

“Burnt” starts as a personal love letter to firefighting.

By the end it also becomes a cri de coeur, a battle cry.

Frank pleads: “If we want our future generations to know what a forest is, if we want breathable air and fatality reduction, we need to stop pretending fire is an unpredictable disaster.”