Illegal underground gig economy booms in NYC as migrants await work permits — all while living off city’s dime

Contact The Author

Contact The Author

Thousands of migrants who flocked to the Big Apple from the US border are making ends meet by working in the illegal underground gig economy — while enjoying the benefits of being put up at taxpayer-funded hotels and shelters.

The Post spoke with 36 migrants over a five-day period, of whom 65% said they were already taking off-the-books jobs in food service and delivery, construction or housekeeping — while city officials generally look the other way, The Post has learned.

Only roughly 800 of the 40,000 adult migrants housed in the five boroughs have filed for federal work permits and of all those The Post spoke to, only one person had applied.

“They are taking jobs from other immigrants,” said Francisco Mata, president of the NY Bodega and Small Business Association. “I’m hearing a lot of complaints from regular citizens, people with papers. It’s getting tough.”

For the newly arriving migrants — about 60,000 of whom are still living on the city’s dime — the illegal gigs are a no-brainer alternative to the laborious, pricey and yearslong process of officially applying for asylum, a prerequisite to qualifying for legal work.

“We’re looking for anyone to hire us that won’t ask for papers,” Senegalese migrant Mustafa Mdiaye, 23, said outside an emergency shelter in Harlem. “We’re looking. We don’t know where.”

But the illegal gigs produce no payroll taxes or other benefits to ease the burden on the city, while taxpayers shell out an astounding $40,000 per migrant, data analyzed by The Post revealed last week.

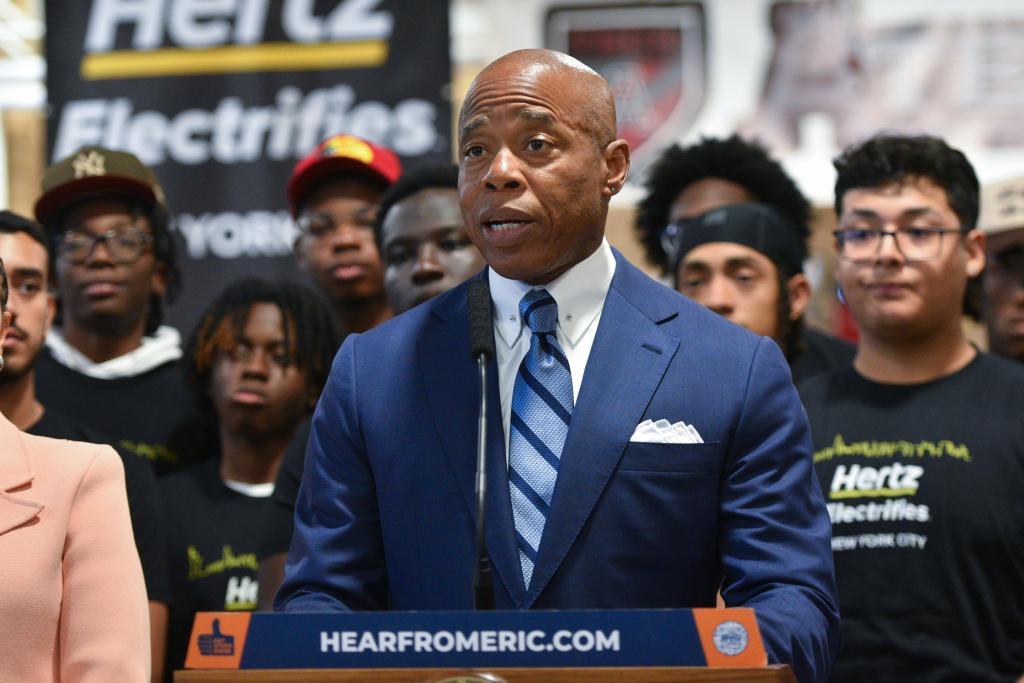

Mayor Eric Adams has estimated that the crisis will cost the city $12 billion by July 2025.

Meanwhile, The Post spoke to a slew of asylum seekers in the five boroughs who admitted they have landed jobs working under the table since arriving in the Big Apple.

Sandra, 22, migrant from Venezuela

Sandra has been living in a Holiday Inn converted to a migrant shelter in Queens with her husband and three children since June.

“I worked in a bar serving small drinks,” she said. “I got paid daily — $60 plus what I earn in tips. I work four nights a week. Sometimes I make $120 per night.

“Thank God I had the capital for my husband to buy a motorcycle so my husband could work,” she said. “I saved up money and gave it to him. He paid $700 for it. I stopped working this week. I stay with the children. I use it to buy food because the children don’t eat the food here.”

Pedro, 35, migrant from Peru

Pedro, who has been housed at a shelter with his wife and four children, has been delivering food in Manhattan by paying a friend $100 a week to illegally use his Uber Eats account, which he sees as his only option while he waits for his work permit to come through.

“I work 10 hours per day, six or seven days a week,” he said. “There are good days and bad days. I use the money I make to support my family and to eat. My wife has a young baby.”

John Hernandez, 37, migrant from Venezuela

Hernandez has been living at the Paul Hotel in Manhattan, listed as a three-star hotel online before it was converted to a migrant shelter. He works as an Uber Eats driver five days a week, eight hours a day. Someone set up an Uber account for him so he can send money back to his family in Venezuela and the Dominican Republic.

He has not applied for asylum or a work permit yet. But he has four children and a wife in Venezuela whom he needs to support. He said the shelter provides most items he needs but he uses some money to buy extra clothes, such as shoes and a shirt for himself.

Moustapha, 27, migrant from Mauritania

Moustapha has been staying at a state-funded tent city on Randalls Island. He heard about a day laborer hiring site outside a Home Depot in Queens and has begun seeking jobs there.

”I’ll make $60, $70 or $80 per day. I’ve never made more than $80 for a whole day’s work,” he said. “Some people, they come, they take you and when you finish, they pay you. Some people are gonna give you $20, $40, $50 for three, four, five hours.

“I accept what they give me because I have no money,” he said. “Sometimes I get here, I sit all day and I get no work.”

The influx of new workers pushes out other migrants who have been picking up day labor for years.

Nick Arevalo, 49, originally from El Salvador, has been coming to the same Home Depot near where he lives in Queens for 10 years, as he lives in the neigborhood.

He told The Post: “Before I’d make good money, $800 per week, depending on the job. For the past two weeks I haven’t made nothing here. People don’t want to pay.

“I paint a room for $150. The new people, they will take less. They say yes to everything.”

In all, more than 113,000 migrants have flocked to New York City since the spring of last year. Those who are still in care are provided housing, meals and other services on the taxpayers’ dime.

Many of the migrants express a desire to seek asylum and become self-sufficient, particularly those with families in the city. The process is also cumbersome and costly, and some told The Post they don’t know how to follow through on their asylum application, let alone how to obtain a federal work permit.

Maria, 19, from Ecuador, who arrived in New York with her husband and 3-year-old son about a month ago, has resorted to peddling bottles of water and soft drinks in Central Park, which she said brings in about $50 a day.

“I don’t have a place to live,” she told The Post. “We sleep outside and on trains.” She added she has not applied for a work permit because she does “not know how to do it.”

Another woman, a Romanian immigrant begging for change at 42nd Street and Fifth Avenue in Manhattan while clutching her baby, admitted she had only been in the Big Apple for about two months, was “undocumented” and could not land an actual job.

“It’s heartbreaking,” Times Square security guard Isaiah Baez told The Post. “Sometimes you don’t even know if they’re sincere but you want to give them the benefit of the doubt because the child’s there.

“Sometimes it could be a con but we’ll never know, so I still give it to them,” he said. “It’s effective.”

Federal rules dictate migrants must wait six months after applying for asylum to get a work permit, a measure designed to discourage migrants from coming to the US for economic reasons.

With a lengthy backlog from the overwhelming influx of migrants in the country, the process is expected to take significantly longer — fueling the thriving underground economy in the meantime.

Adams last week addressed what he called a “black market” economy that’s cropped up over the past 18 months, acknowledging that “it is really going to impact the quality of life in our city.

“And so we’re hoping that the federal government looks at what we’re seeing and make [work permits] happen because I can’t break the law and say, ‘I’m going to allow you to work anyway,'” he said.

However, migrants who have crossed into the US under the Biden administration’s parole program offered through the CBP One app are allowed to apply for work permits right away — though that wasn’t clearly communicated to the migrants themselves. Since September 1, the Department of Homeland Security has sent out thousands of reminder texts to migrants to tell them they are eligible to apply, according to The Marshall Project.

City lawmakers are weighing a 30-day limit to migrant stays in shelters and hotels — half the standard 60-day deadline for single people to reapply for a spot — as an attempt to free up more shelter space.

Adams has also warned about the financial ripple effect of the migrant crisis, saying last week the city may be forced to slash as much as 15% from other Big Apple services that assist New York’s needy.

However, the city has yet to crack down on the illegal gigs.

Officials at City Hall did not respond to a request for comment on Tuesday and instead referenced the mayor’s earlier comments regarding the need for federal work permits.

Additional reporting by Megan Palin, Haley Brown, Jack Morphet, Craig McCarthy and Andy Tillett