Costs of major MTA projects are more than a billion dollars higher than expected: report

Contact The Author

The cost of several new city transit projects has ballooned to eye-popping heights, a report released Wednesday by the Metropolitan Transportation Authority said.

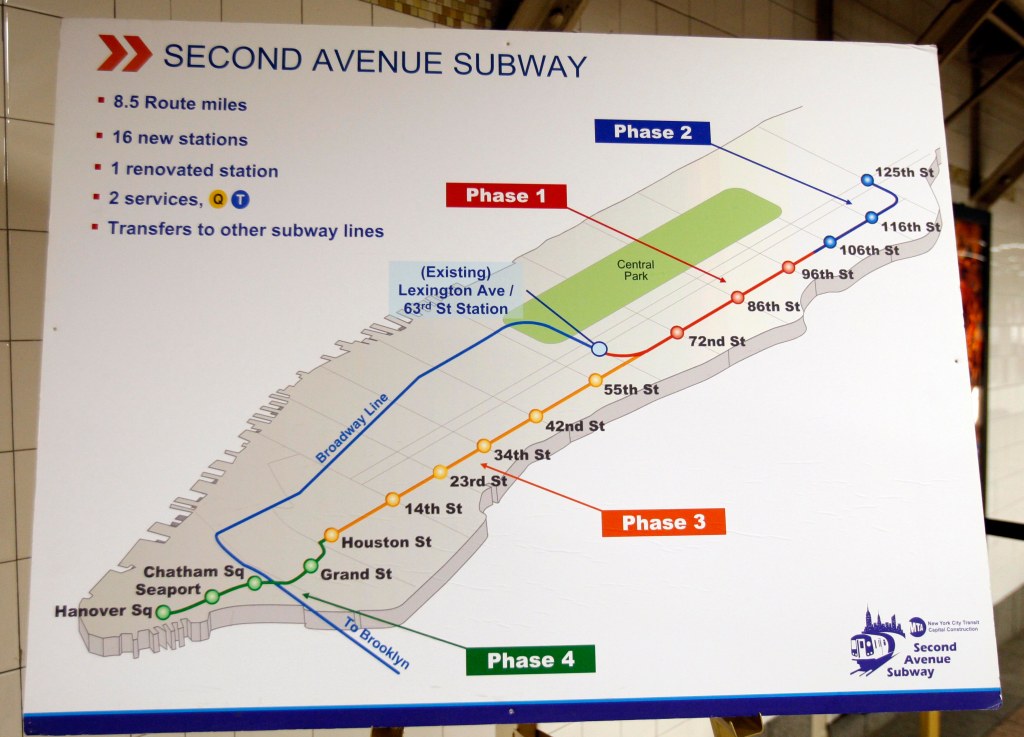

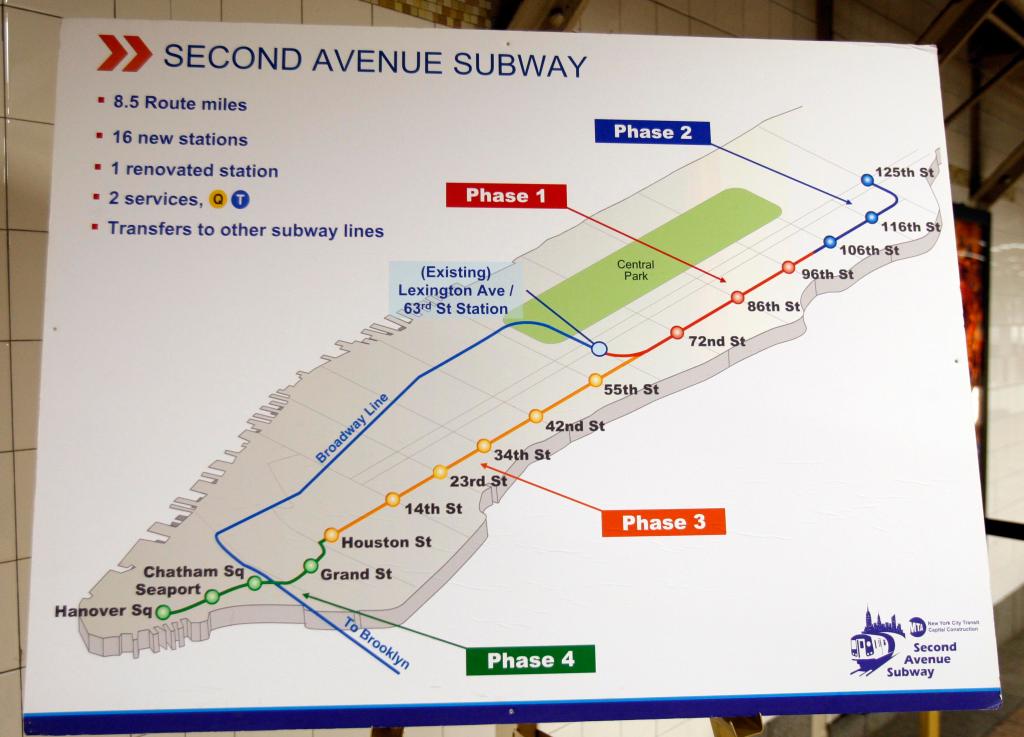

Despite growing scrutiny on costs, the agency revealed massively increased price tags for long-awaited projects, such as a $600 million increase in the cost of a new West Side 7 train station and a $4 billion increase in the cost of the next phase of the Second Avenue Subway.

The new prices of the projects were quietly included deep inside the MTA’s legally mandated assessment of its expected upgrade needs over the next two decades.

MTA officials batted away questions about the spiraling costs during a briefing, arguing the projections were preliminary — while simultaneously arguing they hoped their “groundbreaking comparative evaluation” of the projects would further the debate.

“We’re not committing to making any of these investments, but we’re providing a lot of useful information about the status of the system — and, in this case, the potential costs and benefits of the potential expansion projects,” said MTA construction chief Jamie Torres-Springer.

The high price tags were presented in the report with little explanation:

- The long-hoped-for station on the 7 line at 10th Avenue is expected to cost at least $1.9 billion — up 46% from the $1.3 billion it would have cost when first canceled, adjusting for inflation.

- The southern extension of the Second Avenue Subway from 63rd Street to Houston Street is projected to cost more than $13.5 billion, roughly 40 percent more than the $9.5 billion it would cost when adjusting its original budget for inflation.

- Promised improvements to speed and expand service on the Long Island Rail Road’s Port Jefferson branch saw the price tag balloon from “at least $2 billion” reported to lawmakers in February to more than $3 billion now.

A series of stories in The Post has revealed how excessive station designs and other pricey choices made by outside firms — which the MTA depends upon to plan, design and engineer projects — cause price tags to explode.

For instance, consultants designing the Port Jefferson improvements — which would serve the eastern end of Suffolk County — ordered up an electrical system capable of delivering more service than many subway lines get.

Not every proposal saw its expected cost balloon.

At least one appears to have gotten cheaper: the long-proposed fixes for the Nostrand merge between the No. 2, 3, 4 and 5 lines in Brooklyn.

It’s one of the biggest choke points in the system because trains from each of the four lines — the busiest in the entire system — are forced to cross in front of each other, creating massive jams.

Plans have been drawn up to address the problem since at least the 1960s but were never built.

The proposed fix would build new crossovers to keep the trains out of traffic and reorganize the service in Brooklyn: The No. 2 and No. 3 would turn south and share a terminal at Flatbush Avenue/Brooklyn College, while the No. 4 and No. 5 would continue eastward toward Utica Avenue and New Lots.

Fixing the jam would slash delays and allow the MTA to dramatically increase service on the lines — including potentially creating a new No. 8 line, which would run from New Lots to Wakefield-241st Street in the Bronx.

The MTA estimated the price tag for fixing the merge in 2009 was $343 million, which would cost $491 million adjusting for inflation.

However, as proposed in the planning documents, this latest version of the project would cost just $410 million.

Additionally, officials filled in the blanks on two long-awaited potential subway expansion projects, both of which are targeted at two of the busiest and most congested bus corridors in the city.

The first proposal is newer and calls for stretching the Second Avenue Subway down 125th Street from its current proposed terminus at Lexington Avenue with two new stops: St. Nicholas Ave, where riders could transfer to the A/B/C/D lines; and Broadway, where riders could switch to the No. 1 line.

The stations and roughly 1.2 miles of new subway would cost $7.5 billion to build, officials estimated.

The second, a Utica Avenue subway, has been around for a century.

The biggest proposal would cost an estimated $15.9 billion and build the full line down the four mile stretch from Eastern Parkway to Kings Plaza with seven new stops.

A trimmed-down plan would extend the subway 1 mile southward and construct two stations at Winthrop St. and Church Ave. — and couple the stub with dramatic improvements to the bus service over the rest of the line at an estimated cost of $6.8 billion.

Much of the report focuses on the challenges confronting the subway and commuter rail networks from their aging infrastructure and the rising sea levels and more frequent torrential downpours linked to climate change.

A powerful rainstorm last week flooded key sections of track on the subway and Metro-North commuter railroad, forcing the MTA to suspend most service on both systems for hours.

The powerful September storm came just two months after another flood in July inundated Metro-North’s Hudson River line, which was built along the water’s edge more than a century ago.

However, officials declined repeatedly to put a price tag on the amount of repair and replacement work they believe the MTA’s various systems need.

“The overwhelming conclusion here is that there is a lot more to do — an enormously ambitious set of needs here,” Torres-Springer told reporters.