It is easy to forget that Elon Musk’s main business isn’t being king of the social-media trolls but making cars.

Maybe the news that Tesla has slipped into second place in the electric car market behind a Chinese rival will focus his infamously wandering mind.

(Don’t let marijuana happen to you, kids!)

When Chinese electric-car maker Changan introduced its SL03 sedan in 2022, it was plainly a clone of the Tesla Model 3—such an obvious knockoff that you’d half expect to see them for sale on Canal Street, somewhere between the counterfeit Louis Vuitton bags and the fake Rolex watches.

Other Chinese makers have copied everything from Tesla’s user interface to its website design.

In 2019, Tesla won a settlement from a former employee accused of stealing its Autopilot technology for a Chinese rival.

China has for years been trying to shed its reputation as a “copycat nation,” but old habits die hard, and innovation is dangerous under a police state—it is no surprise that one area where China’s innovators have shone is in developing artificial intelligence tools for surveillance.

Keep that in mind when digesting the news that China’s BYD has surpassed Tesla in electric-vehicle sales.

BYD is an exemplar of the Chinese copycat model, having got its start in the automotive business by simply reverse-engineering and ripping off competitors’ designs, including innovative work from Toyota and Mitsubishi.

But, like the United States, China has a very large domestic market, and a company can grow quite large and sophisticated even within the walled garden of China’s protectionist economy.

And the walls are not coming down:

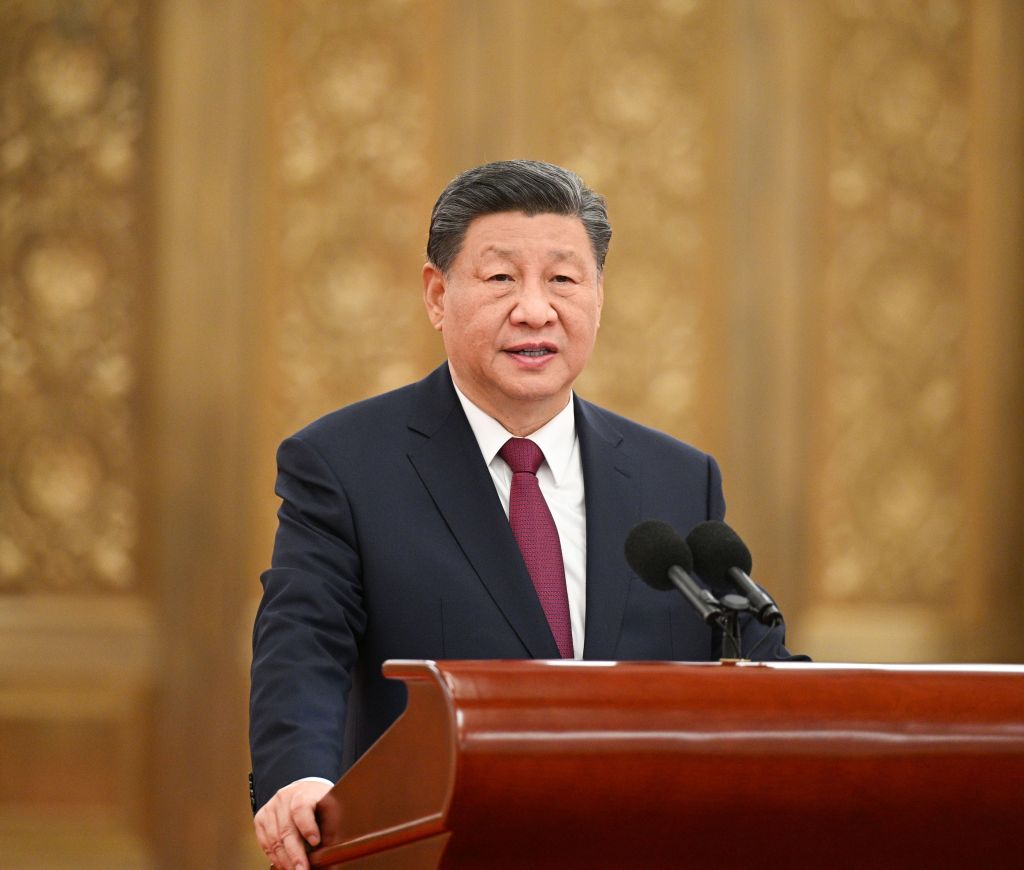

Rather than continuing the move toward markets and open exchange begun by his predecessors, the true-believing socialist Xi Jinping has made it clear that he thinks liberalization has in some cases gone too far and that it is high time for Beijing’s central planners to reassert themselves.

That may make sense politically for Xi but, as economics, it is pure self-harm, as China’s current economic straits have made so abundantly clear that even Xi himself has been forced to admit his country is in trouble.

Chinese economic protectionism is complicated because of the prevalence of state-owned (including military-owned) players and internal factional rivalries.

For example, subsidies at the regional level to boost local automakers and other hometown firms over other Chinese competitors cost Chinese consumers billions of dollars a year.

Firms such as BYD may not be explicitly state-owned, but they are state dependents, part of a cozy, nasty little circular flow of money and power between the CCP and the notionally private market.

For example, when the authorities in Shenzhen mandated that taxi fleets switch to EVs, it was no surprise when Shenzhen-based BYD was chosen to supply them —resulting in more than 21,000 sales for the firm.

Beijing screams and howls when, for example, the European Union launched an investigation into whether Chinese EV subsidies are significant enough to trigger EU anti-“dumping” measures, but nobody in his right mind believes that Tesla and BYD are playing by the same rules in the Chinese marketplace.

And, really, for the most part, that’s fine: Yes, free markets and free trade would be better for everybody, but the real costs of Chinese protectionism are born in the main by Chinese consumers, who are forced to accept a lower standard of living to line the pockets of politically connected business interests and party bosses.

The same largely holds true in the United States: The idiotic U.S. war on Canadian lumber benefits a small number of influential U.S. businessmen at the cost of consumers who pay more for things made out of wood, such as houses.

China is going to do what China is going to do, and Xi Jinping will do whatever he can to hold on to power for the same reason Vladimir Putin will: There is no retirement plan for gangsters. Tesla should not expect to find many friends in Beijing.

But if I were advising Elon Musk, what I would tell him (other than to wean himself off of his moronizing social-media platform) would be to worry less about Chinese knockoffs and more about EV competitors from big, well-established firms such as Mercedes and VW Group.

Tesla may tower over them when it comes to market capitalization, but VW still sells about five cars a year for each one Tesla does.

Tesla may get credit for creating the modern EV market—and, in that, Elon Musk’s achievement has been truly extraordinary, whatever one thinks about his online antics—but being the first mover doesn’t always confer a lasting advantage.

In 2023, customers looking to buy one of Porsche’s electric Taycan sedans faced waiting lists up to 18 months, so great was the demand.

Mercedes is having real success with EVs.

Musk may have created something ex-Nihilo with Tesla, but Mercedes has been selling cars successfully for about as long as there have been cars, and it is going to be a tough competitor.

As usual, markets ultimately will work this out, whatever strongman shenanigans Xi Jinping tries to pull. But that doesn’t mean that markets will work this out in Tesla’s favor.