They had finally gone and done it. They’d found their dream house. Gary and Sandy Carter, a couple of California kids, had finally decided to plant permanent roots in their adopted city, Montreal, and why not? Gary had just completed his 10th full year in pro ball, all with the Expos. He’d made six straight All-Star appearances.

He was the face of baseball in Montreal.

And then the phone rang.

“And at first,” Sandy Carter says, “it almost felt like a joke. They were calling Gary and asking if he’d be interested in being traded. To New York, of all places.”

The Expos needed to ask, too. As a 10-and-5 man — 10 years in the majors, five with the same club — Carter couldn’t be traded without his permission. But the Expos — who’d come so close to making the World Series in 1981, losing the NLCS to the Dodgers when Rick Monday hit a ninth-inning home run in decisive Game 5 — were nearing a rebuild.

And the Mets were offering a haul, identifying Carter as the final piece to a championship tapestry.

“And there was one other thing,” Sandy Carter says with a laugh. “There was Dwight.”

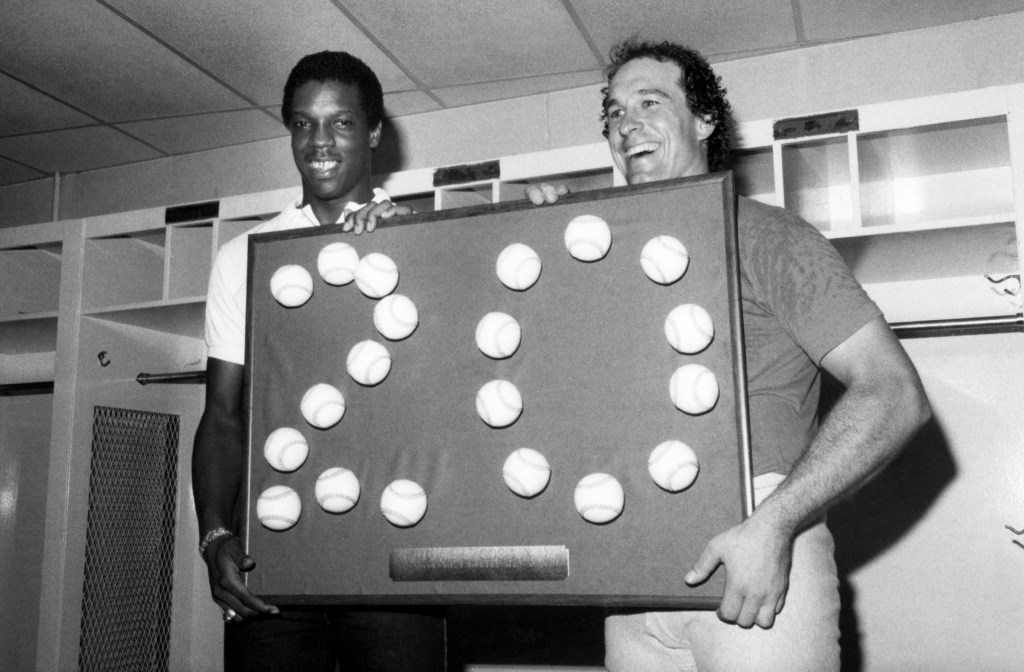

A year earlier, as a 19-year-old, Dwight Gooden had taken baseball by storm, a kid with gasoline in his right arm and a precocious predilection for dominating good hitters. Carter had found that out the hard way, striking out four times in 13 at-bats against him in ’84. But he’d also learned it in an unforgettable way, too.

On July 10, Gooden became the youngest player to ever take part in an All-Star Game when he entered in top of the fifth inning at San Francisco’s Candlestick Park. And in 15 pitches, he blew the sport away: he struck out Lance Parrish, Chet Lemon and Alvin Davis, and he had veterans shaking their heads.

“It was ballet,” no less an expert on fireballing than Goose Gossage said. “It was beautiful to see. It was the greatest pitching I’ve seen in a long time.”

to him before a Mets game against the Diamondbacks in 2010. Paul J. Bereswill

Gary Carter had caught all 15 of Gooden’s pitches. Later, he told his wife: “That kid has something special. He’s beyond special.”

And now, five months later, the memory of that summer night returned to Carter. And much as he had grown to love Montreal, he knew where his destiny now lay.

“I can catch that kid 30 times a year,” he said. “How could anyone say no?”

Says Sandy: “And that was the beginning of an amazing friendship.”

Sandy Carter will be among the honored guests Sunday afternoon when the Mets retire Gooden’s No. 16 jersey, 40 years after he first exploded into the sport, 40 years after Dr. K became the brightest star in sporting New York, so big that for nearly 10 years, a Nike ad of him — 95 feet high, 42 feet wide — occupied the entire side of the Holland Hotel in Manhattan at 351 W. 42nd St.

So big that a couple of kids from North Haledon, N.J. — Dennis Scalzitti and Bob Belle — used to bring 27 posterboards with the letter “K” on them to their seats up in the left-field upper deck at old Shea Stadium, up in Section 44, where start after start they would hang on after each strikeout. And thus was the “K Korner” born.

“We always brought 27,” Scalzitti said. “Because you never know.”

It was an unlikely friendship, Gooden and Carter. The catcher was already a family man, devout and disciplined, an outlier on a team that played hard on the field and played harder off of it. Gooden landed at the Smithers Institute in the spring of 1987, and he relapsed frequently in the years ahead.

“And Gary would always reach out to him, offer him encouragement, tell him he loved him, and he’d visit with him whenever he could,” Sandy Carter says. “They had a wonderful relationship from the day Gary joined the Mets and it only grew stronger through the years. They trusted each other implicitly.”

This was true on the field — “Dwight told me years later that he never shook Gary off, not once, he knew Gary knew exactly what pitches he needed to throw,” Sandy says. But it became a stronger bond later on. At first, it was Gary trying to coax Doc through the dark times. Later it reversed, once Carter received his cancer diagnosis, and later still when the prognosis grew dim.

“Dwight called all the time,” Sandy says. “And they always had the same message for each other.”

“You can beat this,” Gary told Doc.

“You can beat this,” Doc told Gary.

Gooden fell into relapse several times. Carter finally died on Feb. 6, 2012, a little less than nine years after he was elected to the Hall of Fame. His best years came in Montreal. But his most glorious ones came in New York.

“Gary caught a lot of great pitchers,” Sandy says. But he always said his favorite, 100 percent, was Dwight. If he could be there [Sunday], I can promise you nobody would be happier, nobody would be prouder, than Gary.”

Sandy Carter laughs.

“He loved him,” she says. “They loved each other.”