US’ first case of mass hysteria might have something in common with Havana Syndrome

Dizziness. Chirping in the ears. Migraines. Memory loss. These are just a few of the symptoms of Havana Syndrome — the mysterious sudden-onset illness that is said to have affected more than 100 US diplomats, White House staffers, intelligence agents and their family members.

Last Wednesday, the House homeland security subcommittee on counterterrorism, law enforcement and intelligence heard testimony from retired army officer Greg Edgreen, claiming that “America’s best men and women in national security are being targeted and neutralized.”

This echoed a “60 Minutes” bombshell report that aired March 31, claiming Russian intelligence operatives could be behind the debilitating syndrome that first surfaced in Havana, the capital city of communist Cuba.

Theories about the cause have included the use of electromagnetic or radio frequency energy, chemical attacks, ionizing radiation or acoustic signals. But multiple US intelligence agencies insist that the culprit is not a foreign adversary.

Instead, the FBI’s Behavioral Unit, and others in the scientific community, believe Havana Syndrome’s victims were probably suffering from “mass psychogenic illness,” when people start feeling sick even though there is no physical or environmental reason for their illness.

It’s similar to a “mass hysteria” that terrorized the residents of a small town in the American heartland during World War II — who believed they had been sickened by a madman who gassed or anesthetized them while they slept in their beds.

Long lost to history, this year marks the 80th anniversary of the hysteria that struck dozens of working-class residents of Mattoon, Illinois, who claimed to have suffered from some of the same symptoms that have befallen Havana syndrome victims today.

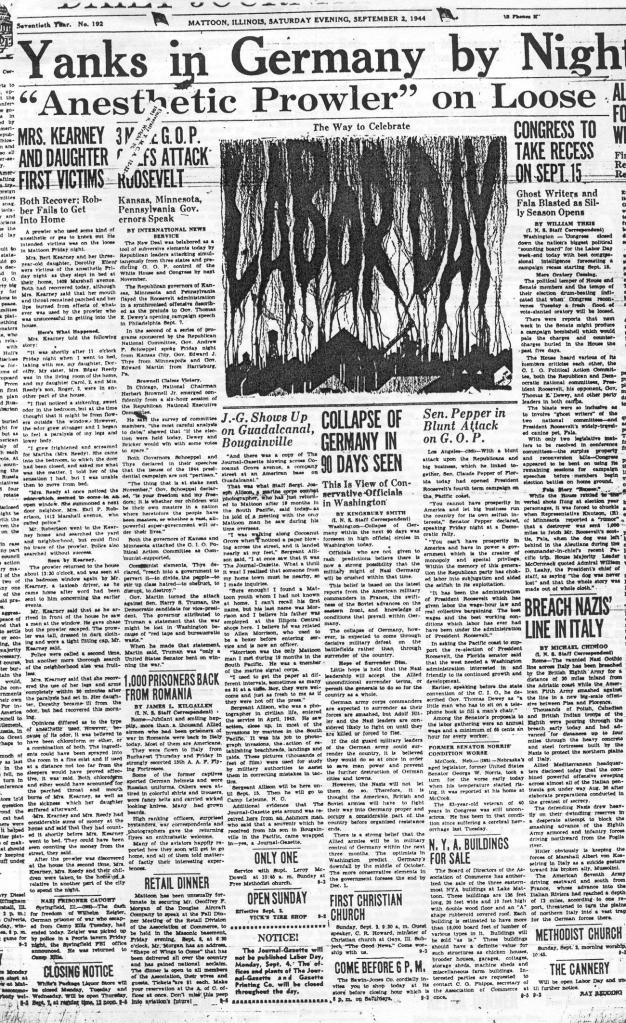

The Mattoon case became public for the first time on September 1, 1944, when a local newspaper reported an interview with Aline Kearney, a cabbie’s wife and mother of three-year-old Dorothy Ellen. She had gone to bed around 11 p.m. and noticed a “sickening, sweet odor” that “grew stronger and I began to feel a paralysis of my legs and lower body.

“I grew frightened and screamed for Martha,” her sister-in-law, who “at once noticed the odor.”

She summoned a neighbor who called the police, which was now down to just 10 officers because of the wartime draft.

Upon arrival, officers were told a mysterious figure in all black had been spotted near the house, and that he had used an anesthetic — chloroform, ether, or a combination of both — to make Aline Kearney ill.

Some 90 minutes later, her husband arrived home, spotted a tall figure at the window — a man, and possibly a woman, who would soon be dubbed ‘The Mad Gasser of Mattoon.”

Mr. Kearney gave chase and the police were called once again, but the search was fruitless. By then, Mrs. Kearney’s paralysis was gone and she had recovered the use of her legs and arms.

Virtually overnight, more Mattoon residents reported being gassed by the supposed fiend. In all, several dozen claimed to be victims by the time the scare ended weeks later.

The story hit the big-time national media, including Time magazine and the Associated Press — with the latter reporting: “Mattoon gets jitters from gas attacks, comparing nervous Mattoon residents to Londoners under protracted aerial blitzing.”

According to the September 18, 1944, issue of Time, “The Mad Anesthetist began his nocturnal visitations two weeks ago, mainly concentrating his fiendish attacks on women. One said a smell like gardenias ‘made her legs tingle.’ Another said a ‘fat man had squirted perfume into her bedroom.'”

An account from Mrs. Carl Cordes got wide play, after she claimed to have found a damp pink cloth on her back porch.

Cordes said she sniffed it out of curiosity, fell ill and told police she “felt as though a charge of electricity had gone through me.” Taken to the hospital, she had reportedly suffered temporary paralysis and, incredibly, burns.

Keep up with today's most important news

Stay up on the very latest with Evening Update.

Thanks for signing up!

An investigator from the Illinois Criminal Investigation Laboratory was dispatched to Mattoon from the Windy City, 230 miles away, to probe the pink cloth, but the lab found no evidence of gas, or any chemicals on it.

But the investigator, one Richard T. Piper, nonetheless announced that he thought the “anesthetist” was probably using a heavy, colorless liquid of some sort. Meanwhile, five Chicago chemists called the whole case a “hoax.”

With Mattoon gripped by fear, the police and townsmen formed a virtual posse in search of the monster — like a scene out of Frankenstein, but using flashlights instead of torches. Vigilantes armed with shotguns patrolled the deserted streets at night, prompting Mattoon’s alarmed police commissioner to declare, “I wouldn’t walk through anybody’s backyard at night now for $10,000.”

Police Chief C.E. Cole demanded that “roving bands of men and boys should disband. They’re in grave danger of being shot.”

Locked and barred in their homes, frightened residents took loaded weapons to bed with them.

At the same time, as Time noted, “Chicago newsmen swept joyfully down upon Mattoon and wired leering accounts of The Gas Fiend, The Thin Man of Mattoon, The Mad Phantom and The Screwball Chemist.”

At one point during the first two weeks of that hellish September, 17 families on just a single Mattoon block claimed they had been gassed, causing nausea and weird feelings to their arms and legs.

But near the end of the month, with little or no attacks reported, and with no suspect caught, there were serious suspicions that a gasser — and the gas — never existed.

It was then that the Illinois state’s attorney, William Kidwell, shut down the case, declaring that the Mad Gasser was clearly a wave of mass hysteria that had consumed the town. Blame was also placed on journalists who had hyped the story from day one — when Mattoon’s Daily Journal-Gazette front-page headline about the Kearney case read, “Anesthetic Prowler on Loose.”

The Illinois Times chalked it up to wartime madness, noting that “when so many men were off fighting and so many women left alone, the gassings have been explained away as a product of paranoia, panic and delirium.”

As for today’s controversial cases, a report — “Havana Syndrome: A Post Mortem” — in the March issue of the International Journal of Social Psychiatry concluded that the six-year investigation by US officials was like going down a “rabbit hole” in the search for “exotic explanations.”

“Instead of finding secret weapons and foreign conspiracies,” the report said, “they found only rabbits.”