These days many liberals embrace the “easy money” culture of generous government relief and low central bank interest rates as a way to pay for social programs and ease the wealth gap.

But they should beware of what they wish for. Because contrary to popular belief, big government has been accelerating the rise of the billionaire class that liberals despise most.

In recent decades, the markets for stocks, bonds and other financial assets have tended to move only one way, up — levitating on a magic carpet of money flowing out of the Treasury and the Federal Reserve.

Many observers object that Wall Street has been gaining at the expense of Main Street. Even titans of finance warn that growing wealth gaps could trigger a more or less violent “revolution.” Prominent politicians want to “abolish” billionaires—a call never heard before in the United States.

But they are calling for more of the same strategy—heavy market intervention—that twisted capitalism into “socialism for the very rich” in the first place.

Government is not the enemy, it is the enabler of the power elite. By soaking capitalism in complex debt and regulation, it creates a system that only the richest tycoons and corporations are best equipped to navigate.

In many capitalist countries, the share of wealth held by the richest citizens has been rising for decades. In the United States, the share of national wealth controlled by the richest one percent has roughly doubled to 35% since 1980, mainly at the expense of the upper middle classes; the poorest 50% never had much to lose, the bottom 25% have had negative net wealth for nearly two decades.

Today, their debts are often bigger than their assets, which ultimately leaves them with less than nothing.

These shifts represent the distribution in gains one would expect in a period when easy money is both flooding the economy with debt, and pumping up the value of financial assets.

The richest one percent of Americans now own, for example, 54% of all stocks by market value; the next 9 percent control 39%, and the bottom 90% own just 7 percent.

As government comes to the rescue more assertively each time the markets falter, it turns the markets into a kind of perpetual motion machine, widening wealth inequality. And popular anger follows.

In the early 2000s, the share of American wealth controlled by the 1 percent eclipsed that of the 90% for the first time in decades—a harbinger of upheavals to come.

By the 2010s, the revolt was on, and its prime target was not the one percent, it was billionaires, or the 0.00003 percent. In 2016 Bernie Sanders became the first presidential candidate to explicitly attack “the billionaire class.”

Four years later, as Democrats hammered the fact that the richest 3 Americans control more wealth than the bottom 50%, Joe Biden was vowing to tax billionaires back down to size. “It is fascinating that for the first time in my life, people are saying, ‘Okay, should you have billionaires?’” marveled Bill Gates.

Many liberals look for answers to this growing divide in all the wrong places: Most notably, the more carefully managed capitalism of Europe. Bigger governments across the pond have not contained the billionaire class, quite the opposite.

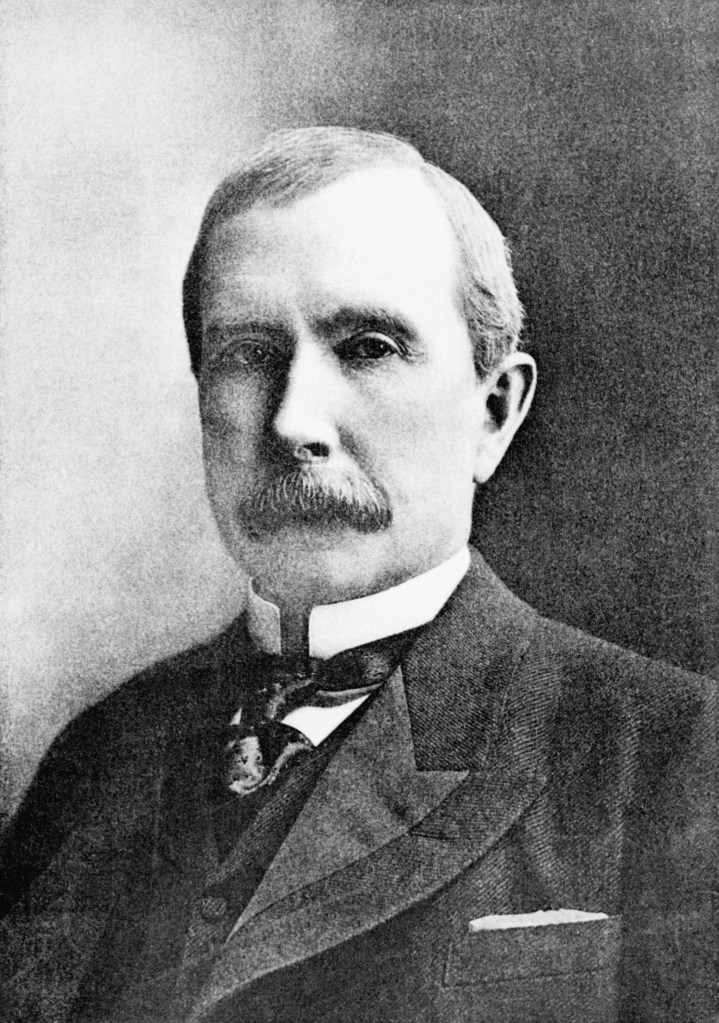

In the early 20th Century, oil baron John D. Rockefeller saw his fortune peak at 1.6 percent of GDP—a record for the United States.

By 2021, when massive government interventions were sending markets skyward despite the shock of the pandemic, the world had at least 17 modern-day moguls with Rockefeller-like control of their economies—but not one in the United States (not even Jeff Bezos or Elon Musk).

Instead, they were found in more generous welfare states, from Canada to France. Sweden, often hailed by American progressives as a socialist success story, had the most: five billionaires with wealth in excess of 1.6 percent of their nation’s GDP.

Defenders of big government argue, broadly speaking, that while easy money may lift financial markets and therefore wealth at the top, it also creates jobs.

So any increase in wealth inequality is compensated for—in large part—by rising incomes for everyone.

The problem: income inequality has also widened as the culture of easy money spread.

Talk of “a new gilded age” has been around a while, but it is no longer just talk.

Since 1980, the income share of the one percent has doubled, recently surpassing 20% for the first time since the 1920s—and rising (as with wealth) mainly for the super rich, at the expense of the upper middle classes, as the share of the bottom 50% stagnates at a low level.

When capitalism is working, government is small enough to leave room for individual freedom and initiative, encouraging new and small enterprises to rise up and creatively reimagine old concentrations of wealth and power.

To right the balance, the sensible answer is less government, reducing the flow of easy money and bailouts that help the big grow bigger, and the welter of regulations that make it hard for the small and nimble to compete.

If liberals want to make capitalism fairer, without destroying it entirely, they need to embrace “creative destruction” and abandon the easy money culture. It’s the safety net for billionaires.

This excerpt was adapted from What Went Wrong With Capitalism by Ruchir Sharma published this week by Simon & Schuster.