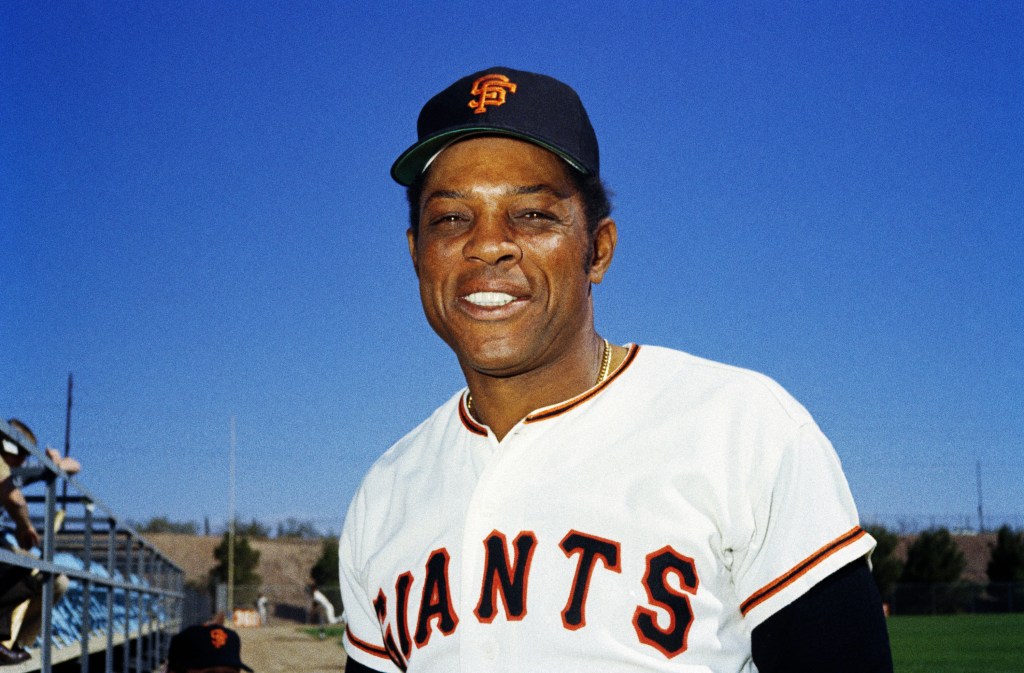

Willie Mays, baseball icon, dead at 93

Contact The Author

Willie Mays, who, when he wasn’t playing stickball with neighborhood kids in the streets of Harlem, helped extend New York’s golden age of baseball into the late 1950s when he played for the Giants, died Tuesday of heart failure.

He was 93 and at the time of his death was the game’s oldest living Hall of Famer.

Known as the “Say Hey Kid,” Mays, who joined the Giants early in the 1951 season, played 22 major league seasons and is still recognized by many as the greatest all-around player in baseball history.

All but his final two seasons came with the Giants, either in New York or San Francisco where the franchise relocated following the 1957 season.

He was traded to the Mets in May 1972 at the age of 41 and finished his career in Flushing, retiring following the Mets’ seven-game loss to the Athletics in the 1973 World Series.

The Mets, fulfilling a promise made to Mays long ago by then owner Joan Whitney Payson, retired his No. 24 — which had been worn by Rickey Henderson and Robinson Cano, among others — at a ceremony in August 2022.

The Giants had retired his number 50 years earlier and Mays became the 15th player in major league history to have his number retired by multiple teams.

Despite a lasting image of a sadly diminished Mays falling down in center field while trying to track a fly ball at the Oakland Coliseum in Game 2 of that World Series, he left baseball as a two-time NL MVP and the author of 3,283 hits and 660 home runs, twice hitting as many as 50 in a season.

At his retirement his was the third-highest home run total in major league history, behind only Babe Ruth (714) and Hank Aaron, his contemporary who would go on to hit 755 home runs.

The winner of 12 consecutive Gold Gloves, Mays, who popularized the basket catch and was renowned for running out from under his cap as he flew around the base paths, was named to a record-tying 24 NL All-Star teams — there were two All-Star games each season from 1960-62 — joining Aaron and Stan Musial.

24-time All-Star, 12-time Gold Glover, 2-time MVP, World Series champion, Hall of Famer.

— MLB Network (@MLBNetwork) June 19, 2024

MLB Network mourns the passing of one of our game’s most iconic figures, Willie Mays. pic.twitter.com/gQLCnbm2lN

“They invented the All-Star Game for Willie Mays,” said Ted Williams.

Mays was inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1979, at the time just the ninth player enshrined in his first year of eligibility.

Mays received 94.7 percent of the vote, at the time the fourth-highest percentage ever and trailed only Ty Cobb (98.2), Babe Ruth (95.1) and Honus Wagner (95.1).

But 23 of the 432 members of the Baseball Writers Association of America failed to vote for Mays, causing Dick Young, later a Post columnist, to write, “If Jesus Christ were to show up with his old baseball glove, some guys wouldn’t vote for him. He dropped the cross three times, didn’t he?”

Willie Howard Mays was born May 6, 1931 in Westfield, Ala., where his father played for the Negro team at the local iron plant where he worked.

Mays’ mother was a standout high school athlete.

Before he had even graduated high school, Mays was playing for a minor league team in the Negro Southern League.

Within a year he was playing for the Birmingham Black Barons of the Negro Major Leagues.

On the day he graduated high school in 1950, Mays signed with the Giants for $6,000, and after hitting .353 in Trenton, he batted .477 in 35 games the following season for their Minneapolis affiliate.

By late May of that 1951 season, Mays was in the major leagues. He had just turned 20.

“Leo Durocher was our manager and he brought Willie up to me and said, ‘This is Willie Mays and he’s your new roommate,’ ’’ said Hall of Famer Monte Irvin, an outfielder/first baseman with the Giants. “You could see right away that this young man was a natural. He had those real big hands, great power and speed and would catch everything hit in his direction. He’s the best center fielder that ever lived, no question.

“I think anybody who saw him will tell you that Willie Mays was the greatest player who ever lived.”

Said rival NL manager Charlie Grimm, “Mays can help a team just by riding on the bus with them.”

But all that was still to come. Mays’ arrival in New York followed by only a few weeks the debut of another precocious rookie center fielder, 19-year-old Mickey Mantle of the Yankees.

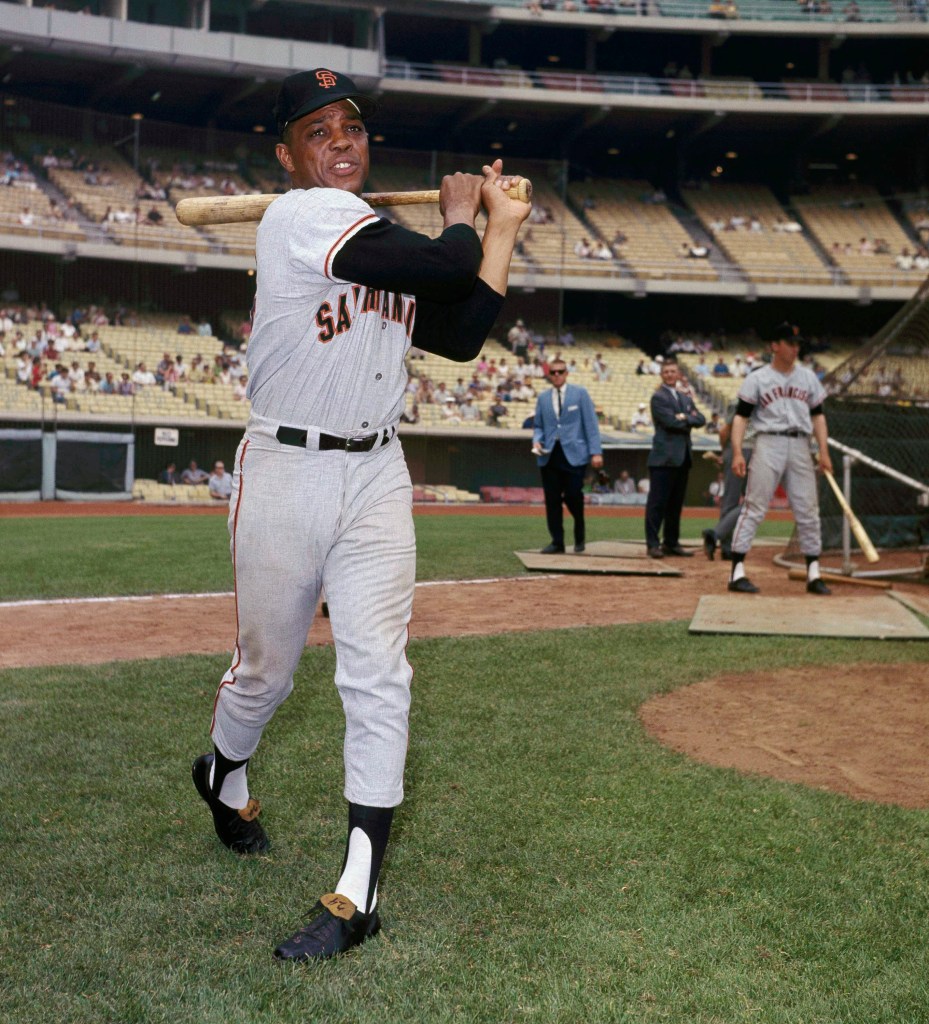

batting practice prior to the start of an Major League Baseball game. Getty Images

Thus began the debate as to not only who was the best center fielder in New York but who was the best young player in the game.

Like Mantle, Mays struggled early, getting just one hit — a home run — in his first 25 at-bats.

But he would go on to hit .274 with 20 home runs in 121 games that season, winning NL Rookie of the Year honors and helping the Giants claw their way back from a 13 ¹/₂-game deficit in mid-August to win the NL pennant in a dramatic three-game playoff with the Brooklyn Dodgers.

Mays was in the on-deck circle in the Polo Grounds that October afternoon when Bobby Thomson slugged what became known as “The Shot Heard Round the World,” a three-run homer in the bottom of the ninth inning that sent the Giants to the World Series for the first time since 1936.

The Giants would lose that 1951 World Series in six games to Mantle and the Yankees, who were in the midst of winning five consecutive Fall Classics.

Playing right field in Game 2 of that series, Mantle tore knee ligaments when he stepped on a drain in the Yankee Stadium outfield while going after a ball hit by Mays.

Any debate about whether Mays or Mantle was the better all-around player ostensibly ended that afternoon when Mantle crumpled to the turf.

President Biden called Mays “unique” and “original in so many ways” in his statement about the great’s passing.

“Like so many others in my neighborhood and around the country, when I played Little League, I wanted to play centerfield because of Willie Mays,” Biden said. “It was a rite of passage to practice his basket catches, daring steals, and command at the plate – only to be told by coaches to cut it out because no one can do what Willie Mays could do.”

After missing part of the 1952 season and all of the following season when he was drafted into the Army during the Korean War, Mays returned with a vengeance in 1954.

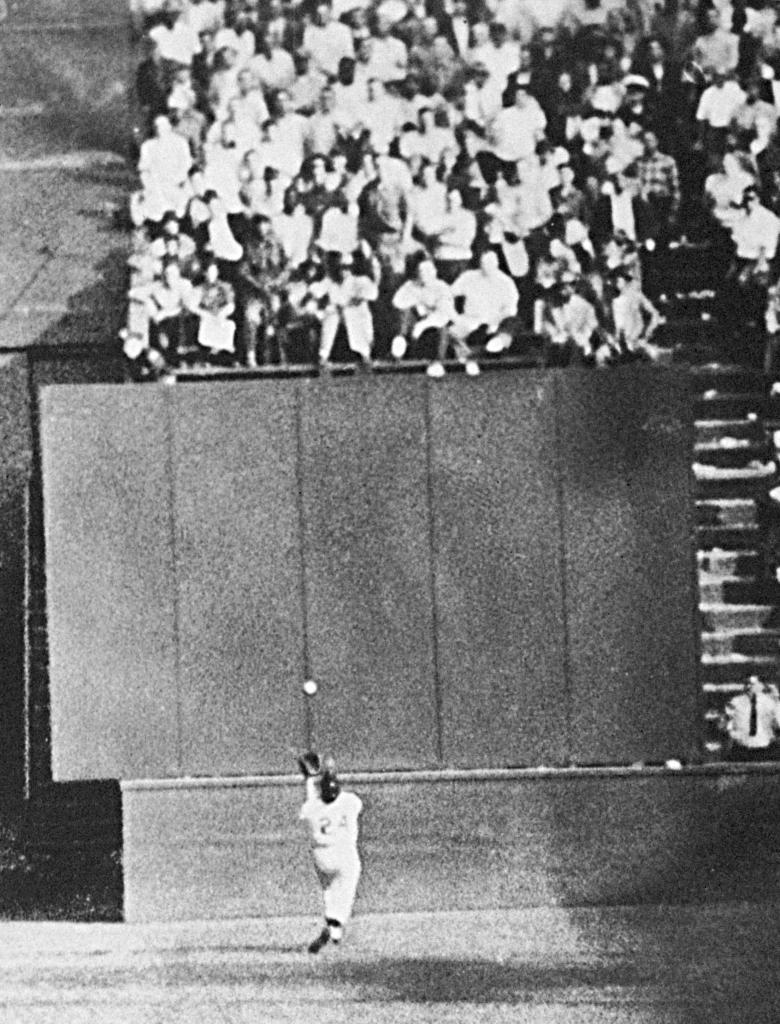

He led the NL in hitting while slugging 41 home runs to win his first MVP award. Mays’ breakout season led the Giants to the pennant and a four-game sweep of the Indians. It was in Game 1 of that series that Mays made what became the signature defensive play of his career, known simply as “The Catch.”

back to the plate, gets under a 450-foot blast off the bat of Cleveland

Indians first baseman Vic Wertz to pull the ball down in front of the bleachers

wall in the eighth inning of Game 1 of the World Series. AP

In the eighth inning, with Indians on first and second and nobody out, Cleveland first baseman Vic Wertz hit a drive to deep center field.

Mays turned his back to the infield and raced to the deepest recesses of the Polo Grounds where he caught the ball over his shoulder some 450 feet away from home plate. He quickly turned and threw the ball back in toward the infield, pirouetting as he lost his balance and his cap.

“I had it all the way,” Mays would say.

While many believed was the greatest catch Mays ever made, the center fielder was noncommittal.

“I don’t compare ’em,” he said. “I just catch ’em.”

In the bottom of the 10th that afternoon, Mays walked and stole second.

After an intentional walk, pinch-hitter Dusty Rhodes smacked a three-run homer that gave the Giants a 5-2 victory on their way to a surprising sweep.

It was their final world championship in New York.

From 1954-63, Mays batted lower than .300 just once (.296 in 1956). His highest batting averages were .347 in 1958, the Giants’ first year in San Francisco, and his league-leading .345 in 1954.

In 1955, Mays led the league with 51 homers.

The following season he hit 36 homers and stole 40 bases, to become only the second member of the 30-30 club.

In 1957, in the first year the award was presented, Mays won his first Gold Glove. He, Roberto Clemente, Al Kaline, Andruw Jones and Ken Griffey Jr. are the only outfielders to win 10 or more Gold Gloves.

That season, Mays also became the fourth player in major league history to join the 20-20-20 club (doubles-triples-homers), something no one had accomplished since 1941.

“I can’t believe that Babe Ruth was a better player than Willie Mays,” said Sandy Koufax. “Ruth is to baseball what Arnold Palmer is to golf. He got the game moving. But I can’t believe he could run as well as Mays and I can’t believe he was any better an outfielder.”

The Giants headed west for the 1958 season, and if Mays had trouble acclimating himself it didn’t show.

1966. AP

He recorded the highest batting average (.347) of his career — vying with Richie Ashburn for the batting title until the season’s final day when Mays’ three hits weren’t enough to overtake the Phillies center fielder.

He also hit 29 home runs and drove in 96 while leading the league in stolen bases (31). It was the third of four consecutive seasons in which he led the league in steals.

“They throw the ball, I hit it,” Mays once said. “They hit the ball, I catch it.”

In 1959 he began a run of eight consecutive seasons with at least 100 RBIs and in 1962 led the Giants to their only other World Series appearance of his career.

They lost to the Yankees in seven games.

Mays batted just .250 in that series and drove in one run continuing a string of subpar World Series appearances.

For all his greatness, he batted just .239 with no homers and six RBIs in 20 World Series games spread across four Fall Classics.

In 1963, Mays ended one of the most famous pitching duels in major league history when his homer off Milwaukee’s Warren Spahn in the bottom of the 16th inning gave the Giants a 1-0 win over the Braves.

Starting pitchers Spahn and Juan Marichal each pitched 15 scoreless innings.

Mays won his second MVP award in 1965 after a season in which he hit 52 home runs — one of them the 500th of his career — and drove in 112 while hitting .317.

That season he served as a peacemaker during one of the game’s ugliest brawls involving Marichal and Dodgers catcher John Roseboro.

Mays, who finished in the top five in MVP voting nine times, played in more than 150 games in 13 consecutive seasons from 1954-66.

His 37 homers in 1966 gave the 35-year-old Mays a total of 542. But he never hit more than 28 in a season again, and had just 118 in his final seven seasons.

His 660th and final home run came on Aug. 17, 1973, with the Mets during a season in which he hit just six in 66 games.

Mays had been dealt to the Mets the previous season for pitcher Charlie Williams and $50,000, and had homered in his Mets’ debut to help beat the Giants.

But, aside from that initial home run, his return to New York all those years later was not a triumphant one.

Mays was the oldest position player in the game for his final two seasons.

That was never more apparent than during that 1973 World Series, when he helped the Mets win Game 2 with a clutch single but had all kinds of trouble in the outfield, the part of the ballpark that was once his personal playground.

He left the game as one of two players — Aaron was the other — to have 3,000 hits and 500 home runs. It’s a list that has grown to include Eddie Murray, Rafael Palmeiro, Alex Rodriguez and Albert Pujols.

“I think I was the best baseball player I ever saw,” Mays said. “Maybe I was born to play ball. Maybe I truly was.”

In 2015, Mays was presented with the Presidential Medal of Freedom by President Barack Obama.

“I’m proud of this one, man,” Mays said upon receiving the award. “I’ve been kind of blessed in my life with people giving me awards for just playing baseball. You can’t compare this with any baseball award.”

Mays, whose wife, Mae, died in 2013, is survived by a son, Michael, from his first marriage.

He was also godfather to Barry Bonds, baseball’s all-time leader in home runs and a son of Bobby Bonds, Mays’ former Giants teammate.