Dear Reader (including those of you who “won’t take sides on 9/11”),

I saw this video on Twitter this morning of an old shampoo commercial featuring Farrah Fawcett (taking a shower!) and Penny Marshall. Now, as a heterosexual male Gen Xer, it cannot come as a shock to anybody that I have … feelings … for Farrah Fawcett. I don’t want to venture into toxic masculinity or prurience, but I think it is an indisputable fact that Ms. Fawcett was a very attractive lady. She was the most famous of Charlie’s Angels (though not my favorite), and it wasn’t primarily because of her acting skills. Penny Marshall—Laverne from Laverne & Shirley—is very talented and can be very funny. But, if my memory is accurate, no teenage boys had posters of Penny Marshall in their bedrooms or their lockers.

Why this exposition of the obvious?

Well, I texted the video to a group of male friends—all around my age—with the understated comment, “Farrah Fawcett, man.” Similarly implied and explicit compliments were offered.

Then someone—okay, it was me—texted, “Though according to the law of large numbers, there’s gotta be at least one dude out there who sees that video and is like, “Young Penny Marshall … ohhhh mmmm. Yes!”

I didn’t mean to be unkind to Ms. Marshall. I was simply making the point that most men are likely to be more attracted to Fawcett than Marshall, but there are outliers in every large group. Also, the heart wants what the heart wants. I’ll clarify and illustrate the point by taking personalities out of it.

I don’t know any foot fetishists (or, I don’t know that I know any), but I do know that some people are really into feet. In other words, while the male gaze may start with a woman’s feet, for most men it rarely settles there given the other options for visual concentration. The share of women who say, “My eyes are up here!” who are objecting to undesired foot-ogling is very small. However large the web traffic for WikiFeet.com, I am confident that it is much smaller than the traffic for other prurient sites.

Anyway, I thought this would be a fun way to introduce a different way of thinking about conservatism, natural rights, natural law, and the American experiment.

In political philosophy—particularly conservative political philosophy—natural rights and natural law play a large role. Natural law is the older concept, and it holds that there are conceptions of right and wrong that are external to man-made law. The idea starts with the Greeks, but it’s not hard to see how it would play an important role in the Abrahamic faiths. God’s law is, after all, definitionally above man’s law. Natural rights are often bound up in natural law, but they became a distinct category of thought during the Enlightenment. All humans are created in the image of God and are entitled to certain rights and privileges that cannot be taken away by governments. As demonstrated by the Declaration of Independence, the American founding was deeply informed by both natural law and natural rights concepts (even if it failed to live up to them at the outset):

We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness. That to secure these rights, Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed.

Okay, forget about all of that for the moment.

Let’s assume there is no natural law or natural rights in the philosophical or theological sense—that it’s just a numbers game. What I mean by that is, let’s pretend the existentialists and nihilists are right and all notions of morality are just tools of the powerful to regulate the masses. It’s not that “might makes right” so much as the mighty can do whatever they want, because right and wrong are meaningless concepts, at a metaphysical level. The universe doesn’t care if you rape and murder, and the only reasons you should or shouldn’t do “evil” things stem from your own cost-benefit analysis, not some external code of conduct. To the extent such external codes of conduct matter, it’s entirely dependent on how inconvenient the consequences—legal, reputational, or social (i.e., will someone seek revenge?)—might be.

Here’s the thing: You’d still have governments and laws in such a universe, as atheist warlords and kings would still find it useful to regulate violence. Indeed, heedless of natural law, every society regulates violence because it’s in everyone’s interest to have violence regulated, especially for those in charge. Rulers cannot extract rents if there’s no penalty for theft and destruction of property. Subjects will not pay protection money if there’s no protection.

Indeed, this is where states come from. Roving bandits (in Mancur Olson’s phrase) become stationary bandits because they realize they can get a higher rate of return from villages if they don’t raze and ransack them every few years. It’s better to take a smaller slice of a growing pie than destroy the pie by taking it all. This model leads to growing territories, which, over time, become nations, and the warlords become hereditary kings.

We came up with a better system about 300 years ago that took natural rights into account. And that system enabled a superior form of morality, and a more productive society.

Lest you think I’m being wildly self-indulgent here, I just cut 600 words out of this “news”letter (Editor’s Note: Thank you.) on the evolution of nation-states and modern political morality just so I could get to the point quicker. (Quicker—not quickly.) I’ll put it in the comments if you want to read it over the weekend.

Doing The Right Thing

Let’s bring this point down to everyday life. I believe—at a deep philosophical, even spiritual level—that conventional morality, informed by religious and philosophical theories of natural rights and natural law, is superior to the alternatives. But I also believe conventional morality is superior because it works. I’m also fine flipping the causality; it works because it’s superior.

Which brings me back to the law of large numbers. Don’t worry, there’s no heavy math here. All I mean by the law of large numbers is that, in a sufficiently large sample, there will be outliers that seem to defy the rule. There are people who are dealt royal straight flushes twice in a row, for example, but good poker players do not assume this will happen very often. There are wildly lucky stock pickers, but over time it’s wiser to just buy and hold a diverse portfolio than count on your ability to repeatedly defy the odds over time. Put it this way: It’s absolutely true that a sufficiently large number of monkeys banging on typewriters will eventually write Crime and Punishment, but only a fool would make an even bet that any particular monkey will succeed in doing so. (“I’ve got a good feeling about Mr. Bubbles, put it all on him!”) You need really good odds to take that bet.

And now we arrive back to conservatism, shorn of all the fancypants theory. Conventional, boring, bourgeois morality is good not simply because the underlying conception of “the good” is correct, but because it yields the best results.

Like a lot of kids, I used to ask my dad why I—or someone else—couldn’t break the rules. What’s to stop someone from stealing this or that? Why return a wallet with lots of money in it? Stuff like that. His answer always began with, “because it’s wrong” or “because that’s the right thing to do.”

I agree with that, and I’m grateful to my dad for (figuratively) beating that into me. I wish more people would be satisfied with simple declarative moral and ethical imperatives. But I think we fail to impart the longer and more self-serving explanation: It’s also in your interest to be a decent person and follow the rules even when you can—or think you can—get away with breaking them. I don’t just mean it’s good for your soul—which it is. I also mean it’s in your interest because you’re not smart or knowledgeable enough to know when breaking the rules will go horribly wrong for you. The easiest way to avoid getting caught cheating on your wife, for example, is to not cheat on your wife. All other strategies are wildly more complicated.

This is the great thing about boring, traditional morality. Living a decent, honest life is no guarantee against bad things happening to you. But it’s a much more reliable strategy than all the alternatives. Bad things can happen to you on the well-trod path of conventional morality. But at least you know the path is well-trod for a reason. Cutting through the woods invites problems and dangers that people who are smarter and more experienced than you have avoided for a reason.

A lot of parents—and tons of educators—think their job is to make each child or student “special,” implying that being normal, with normal desires and ambitions, is some kind of sad compromise or failure of imagination or ambition. Unleash the inner rebel, the romantic overman, the transgressive artist or activist; indulge the most shocking instincts and desires of each and every child. I would much rather live in a society where parents and teachers clung to the boring, conventional notions of decency, morality, and strategies for happiness. The little Nietzsches, Greta Thunbergs, Pablo Picassos, and random foot fetishists don’t need help or affirmation. They’ll take care of themselves. This is my fundamental small-c conservatism. And I make no apologies for it.

The political analog for all this is to follow the rules—and, yes, those horrible “norms.”

One of the oldest pieces of advice for innocent people caught up in legal scandals in Washington is “don’t lie.” That recommendation is rarely given in theological or moral terms; it’s very practical guidance. If you tell the truth, you don’t have to remember the lies. Moreover, you don’t have to know—or count on—the lies of others in legal jeopardy. And, most of all, you don’t have to worry about anyone finding out the truth. You can only go to jail for perjury if you perjure yourself. Doing things the right way for the right reasons is always preferable, but doing things the right way for the wrong reasons is still better than the alternatives. Because doing things the right way is a hedge against unintended consequences.

We train people to defuse bombs, repair nuclear warheads, feed bears, prepare blowfish sashimi, and fly planes by giving them a clear set of procedures and rules. Shortcuts might work, but the risks of error are a great argument against indulging them. Sometimes bad stuff still happens—that’s life in the universe of large numbers—but following the rules reduces the likelihood of disaster.

This is why they say hard cases make for bad law. Weird outliers create a challenge because you don’t want to change a generally good and valuable rule based on some freak circumstance. A society should be careful about creating a sweeping new rule based on something that has never happened before.

This pulls me into a bit of punditry. I don’t like the Supreme Court’s recent decision on presidential immunity. I don’t think it’s the disaster or outrage some people claim it is, but I also think—for reasons I’ll explore on Saturday’s episode of The Remnant—it was flawed, partly for the reasons laid out in Justice Amy Coney Barrett’s concurrence. But I mostly blame Donald Trump for putting us in this situation. I also blame Merrick Garland and Jack Smith to a lesser extent (for reasons laid out by Jason Willick here). I think Chief Justice John Roberts believes Trump is a one-off, a billionth monkey banging on a typewriter, and he doesn’t want to mess up the constitutional order by deciding a case based on the one guy who yells, “Farrah, get out of the way! I want to see Penny Marshall!”

For all the talk of Trump being a Christian or champion of Christians, I think he’s more like a pagan or nihilist. He thinks all ideas and principles are a waste of time if they inconvenience him. The Founders didn’t have someone like Trump in mind when they wrote the Constitution, they were thinking of George Washington. Trump spent his life in business violating the normal rules, laughing at the people who said, “You can’t do that!” or “You shouldn’t do that!” And it worked for him.

This has resulted in some problematic responses. Trump’s fans don’t want to believe he’s a freak outlier or a statistical fluke. They don’t think he’s the exception that proves the rule, they think he’s the exception that disproves the rule. To them, his success demonstrates that rules and norms were lies this whole time, designed to “rig” the system for the powerful. Trump’s most passionate foes, on the other hand, think the former president’s success has demonstrated that the rules are inadequate, because they haven’t stopped him. Norm-breaking by one team invites norm-breaking by the other in response.

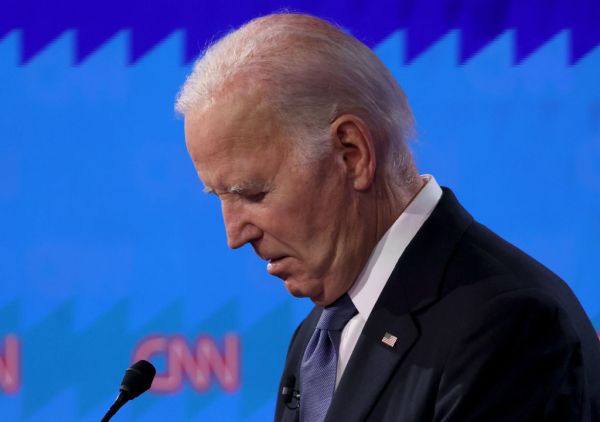

Joe Biden, who has given new meaning to the term “handlers,” has been propped up by people who either knew better or should have known better than to let this man run for office again. I have no doubt that many of them did so for purely selfish reasons. I also have no doubt that they rationalized their selfishness by telling themselves that it was necessary to stop Trump.

This week’s immunity ruling sheds light on something that would have been better kept in the shadows: There’s nothing in our system that outright prevents a terrible man from doing terrible things if he gets in power and enough people want him in power. If you think every job applicant is going to be respectful of the unwritten rules, and if you think voters will only support such people, the need to write out rules against selling pardons or trying to steal an election by force and intimidation seems like a waste of time.

The people angriest at the Supreme Court think that the judicial system should do the job the voters are unwilling to do—stop Trump. Given that I think he’s guilty of many disqualifying crimes, that idea doesn’t bother me. What bothers me is the idea that the courts should deviate from the rules to do it. Charges should have been brought against Trump the day after impeachment (as Mitch McConnell suggested). It is not Chief Justice Roberts’ fault the Department of Justice waited too long and brought needlessly unconventional charges. It’s also not his fault that the Republican Party—elected officials and voters alike—failed in their moral and civic obligation to vomit him out like the poison he is.

I don’t particularly like Roberts’ answer to this dilemma, but he is not the real author of it. We are increasingly living in the worst-case scenario envisioned by John Adams: a society so unburdened by conventional morality or the willingness to demand it from our leaders that the system cannot function as designed.

The only reliable remedy to our political problems is a citizenry willing to do the right thing—and demand that their leaders follow their example.

Canine Update: The dogs hate the heat almost as much as I do (they prefer basking in the air conditioning). Gracie, however, is perfectly fine with it. One of the amazing things about cats is how they can make lying in the baking sun in a fur coat look comfortable. Both Zoë and Pip have been eating a lot of grass lately. For those of you who don’t know, this is often—though not always—a way for them to induce vomiting because they have bad tummies. The other day, I was driving them back from the park in the dog car. Pippa started to do that pre-hurl burbling, like a little Prophet Jonah agreed to leave the spaniel and head to Nineveh and started his march to sunlight. I pulled over, because the last thing a dog-hair-saturated vehicle needs is spaniel yack. But before I could let her out, Pippa daintily stuck her head out the window and barfed in the gutter. She turned back to look at me like, “Now, do you want me to lick your face?” Later she tried to get in the roofers’ van, because she loves them. Anyway, the real hero is Zoë. Kirsten took the beasts on their midday walk with the pack. She slipped and fell. All the little dogs ran over and started shnurffling (it’s a word!) for the treats in her pocket. Zoë, however, stood guard over Kirsten (though some cynics might argue she was standing guard while the little dogs pulled off the heist). Chester is still getting his protection money. I do wish people would stop telling me we should let him in. He has nefarious designs towards Gracie, and always has. Back when Cosmo the Wonderdog was around, Chester would never have dared his occupation of the front doorstep. But Zoë and Pippa cannot be counted upon to stay at their post the way Cosmo did.

ICYMI

And now, the weird stuff: