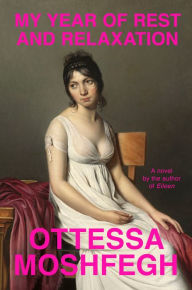

My Year of Rest and Relaxation

Few people’s inner lives are interesting enough to chronicle moment by moment. There’s laundry. Bathroom time. Petty insecurity. Long subway rides. Yet Ottessa Moshfegh hasn’t just walked the literary tightrope that is the existential novel: she’s cartwheeled across. Her new book, My Year of Rest and Relaxation, is an odyssey of consciousness from the perspective of an alienated young woman in the cultural candy store that is turn-of-the-21st-century New York. Moshfegh’s performance is all the more impressive because the protagonist she invented is so unlikely.

My Year of Rest and Relaxation

My Year of Rest and Relaxation

Hardcover $26.00

The short list of well-known existential novels skews French and male. The accomplishment of Moshfegh, a Boston-born daughter of immigrants, is something apart. In My Year of Rest and Relaxation, her twentysomething character sets herself the project of sleeping through an entire year. “Oh, sleep, nothing else would ever bring me such pleasure, such freedom, the power to feel and move and think and imagine, safe from the miseries of my waking consciousness.” Her goal is vague yet ambitious: “a great transformation.” This is no airbrushed Sleeping Beauty undertaking. It requires a criminally negligent psychiatrist, horse-tranquilizer-strength pills, and creative methods for eating and going to the bathroom.

The setting, New York City in 2000 and 2001, allows Moshfegh to plumb a period close enough to the present that her narrator’s concerns are contemporary, yet far enough in the past that it’s easier for her to disconnect than it would be today. (Facebook, for example, didn’t come on the scene until 2004.) More than that, those years, especially in New York, have become radioactive in the public imagination because of the terrorist attacks on September 11, 2001. Its imminence haunts the book, imbuing it with some natural tension. When Moshfegh’s narrator mentions early on that her sometimes-boyfriend, Trevor, works in the World Trade Center, the significance is not lost on readers, though this information is thrown in casually along with the piquant detail that he “asked for head with no shame in the back of cabs he charged to the company account.”

The short list of well-known existential novels skews French and male. The accomplishment of Moshfegh, a Boston-born daughter of immigrants, is something apart. In My Year of Rest and Relaxation, her twentysomething character sets herself the project of sleeping through an entire year. “Oh, sleep, nothing else would ever bring me such pleasure, such freedom, the power to feel and move and think and imagine, safe from the miseries of my waking consciousness.” Her goal is vague yet ambitious: “a great transformation.” This is no airbrushed Sleeping Beauty undertaking. It requires a criminally negligent psychiatrist, horse-tranquilizer-strength pills, and creative methods for eating and going to the bathroom.

The setting, New York City in 2000 and 2001, allows Moshfegh to plumb a period close enough to the present that her narrator’s concerns are contemporary, yet far enough in the past that it’s easier for her to disconnect than it would be today. (Facebook, for example, didn’t come on the scene until 2004.) More than that, those years, especially in New York, have become radioactive in the public imagination because of the terrorist attacks on September 11, 2001. Its imminence haunts the book, imbuing it with some natural tension. When Moshfegh’s narrator mentions early on that her sometimes-boyfriend, Trevor, works in the World Trade Center, the significance is not lost on readers, though this information is thrown in casually along with the piquant detail that he “asked for head with no shame in the back of cabs he charged to the company account.”

Eileen

Eileen

In Stock Online

Paperback

$15.49

$17.00

Moshfegh’s narrator remains unnamed—in contrast to the protagonist of her last novel, Eileen. She is an orphaned heiress living on the Upper East Side, having recently graduated from Columbia with a bachelor’s in art history (the academic major of girls who can afford penurious pursuits). She whiles away her days at a to-die-for gig as the receptionist at a downtown art gallery (until she’s fired and begins her sleep project), pining for the sexploitive Trevor, a finance bro. Did I mention that said narrator is a fashion plate, stick-thin, blonde, and beautiful?

If this character sounds somewhat familiar, that’s because she’s the type to turn up in stories as a detestable foil to illustrate, oh, name it—rampant materialism, shallow mean-girl posturing, the soulless art scene, frat-house eye candy. She’s practically never a fully realized character, perhaps because she’s the kind of person we writers were born to resent. In interviews, Moshfegh has confessed that she was goaded to create a woman like her narrator after readers of Eileen asked her how she could write about someone so disgusting—a young alcoholic with terrible hygiene and a bizarre fantasy life.

Moshfegh wrote Eileen as a stunt. She has said it was her cynical attempt to write a commercial thriller. Instead she produced a startlingly original noir, which was shortlisted for the Man Booker Prize. Subverting the conventional is her calling card. Her short-story collection Homesick for Another World is full of oddball characters who do and think nasty things. It’s no surprise, then, that the shit of the model-pretty narrator in My Year of Rest and Relaxation also stinks. That’s kind of the point.

Moshfegh’s protagonist is deeply unhappy. A central tension of the novel, given all her advantages, is “Why?” In between trips to her derelict psychiatrist for more pills and her corner bodega for more coffee, drop-in visits from her alcoholic frenemy Reva, and blackouts after which she must piece together the events of lost time — whom she’s , what beauty treatments she’s undergone, and whom she’s slept with — Moshfegh offers clues.

Those clues particularize a basketful of cultural maladies: the proliferation of porn and its insinuation into standards of feminine beauty and sexual performance, the veneration of image over substance, the absurdity of what’s categorized as high art (taxidermied dogs) vs. low , McFlurries and I Can’t Believe It’s Not Butter, self-help hucksterism disguised as empowerment, the medication of the American mind, the media’s numbing diet of tragedy, and the internalized self-loathing of young women. Superimposed on all this are more timeless themes. The narrator’s parents, unhappily married, died within six weeks of each other, a loss she’s not yet come to terms with. Her mother was beautiful but cold, and a thoroughly saturated alcoholic. Her father was a distant man whom she couldn’t reach even on his deathbed.

The material may be heavy, but Moshfegh’s treatment of these many themes is deft and ironic enough that they never feel didactic or obvious. In part that’s because they are filtered organically through her narrator’s consciousness. The humor is so dark that sometimes it’s hard to see at all, but it’s there, ready to poke its gremlin nose out at a funeral, an art gallery opening, and in every scene with the psychiatrist, Dr. Tuttle, who says things like, “A lot of psychic diseases get passed around in confined public spaces. I sense your mind is too porous.”

All this said, My Year of Rest and Relaxation isn’t an easy read. Writing instructors like to admonish students that repeated actions or events are to be avoided in fiction. “Write about the day when something different happens.” It’s hard to hold a reader’s attention if you describe your character’s umpteenth trip to the bodega or have her watch Harrison Ford’s Frantic three times in a row. The experience of reading My Year of Rest and Relaxation is not unlike sitting in a deer stand for hours, waiting to catch a glimpse of something other than woods. If you’re patient, a sudden deviation from the norm may offer a flash of insight or emotion. Moshfegh isn’t alone in constructing her narrative on repetitions and habits. This literary trend is evident in novels as varied as Ove Knausgaard’s My Struggle series, Ben Lerner’s 10:04, and Tom McCarthy’s Remainder, to name a few. My Year of Rest and Relaxation is different in that the protagonist is a woman whom the world would have us believe isn’t worth such minute attention. The narrator herself isn’t enamored of her own quotidian minutiae. But in attempting to avoid the bigger, more painful emotions and events in her life, they are all that she is left with.

The narrator’s emotions most often get screen time when her friend Reva appears on the scene. Addicted to revolting alcoholic concoctions (think Jose Cuevo and Diet Mountain Dew) and the perverse advice doled out in Cosmo and Marie Claire, Reva is enmeshed in an affair with her married boss and struggling with bulimia. She has the habit of showing up at the narrator’s apartment at night to drink and kvetch and declare “I love you.” “Maybe she did, and that’s why I hated her,” the narrator muses at one point. If Moshfegh’s blonde zombie has given up, Reva is still striving. The narrator’s professed feelings for Reva oscillate between apathy and contempt, but there are hints of something deeper underneath. When her friend suffers a personal tragedy, the suspense becomes whether the narrator will rally to offer Reva support—which requires her leaving the cocoon of her apartment.

Is this character likable? That question, often dismissed as the canard that distracts middle-brow book clubs from more interesting questions, deserves serious consideration in the case of My Year of Rest and Relaxation. Because Moshfegh’s treatment of her narrator is so granular, readers are invited into the intimacy of this woman’s life. Whether or not we do care about her, we want to. But Moshfegh erects deliberate barriers to our sympathy. Her narrator is a liar, feckless and sometimes casually cruel, casual about her physical advantages. She has the means to conduct an experiment on herself that most of us, with jobs, families, responsibilities, and no source of independent wealth, don’t.

But sympathy doesn’t seem to be the emotion My Year of Rest and Relaxation is after. Perhaps Moshfegh wants us to feel responsible for her creation—and responsible for a culture that makes real human connection so difficult. Her narrator seeks to remain comfortably numb because the alternative is merely fulfilling other people’s vapid expectations. She’s in search of an authenticity that continually eludes her. At one point, observing Reva speak at a funeral, she says, “Watching her take what was deep and real and painful and ruin it by expressing it with such trite precision gave me reason to think Reva was an idiot, and therefore I could discount her pain, and with it, mine.”

9/11, when it eventually arrives, holds out to the narrator the promise of experiencing authentic emotion, but any such relief surely will be temporary. A visit to the 9/11 Memorial Museum reveals that our ravenous culture has consumed this tragedy whole. Below ground in lower Manhattan, history has been commodified into an eternal, smoking present; that tragic day is divvied into a series of emblems and stories crafted from expressions of raw emotion. Yet the effect is still, unmistakably, manufactured

Moshfegh’s narrator remains unnamed—in contrast to the protagonist of her last novel, Eileen. She is an orphaned heiress living on the Upper East Side, having recently graduated from Columbia with a bachelor’s in art history (the academic major of girls who can afford penurious pursuits). She whiles away her days at a to-die-for gig as the receptionist at a downtown art gallery (until she’s fired and begins her sleep project), pining for the sexploitive Trevor, a finance bro. Did I mention that said narrator is a fashion plate, stick-thin, blonde, and beautiful?

If this character sounds somewhat familiar, that’s because she’s the type to turn up in stories as a detestable foil to illustrate, oh, name it—rampant materialism, shallow mean-girl posturing, the soulless art scene, frat-house eye candy. She’s practically never a fully realized character, perhaps because she’s the kind of person we writers were born to resent. In interviews, Moshfegh has confessed that she was goaded to create a woman like her narrator after readers of Eileen asked her how she could write about someone so disgusting—a young alcoholic with terrible hygiene and a bizarre fantasy life.

Moshfegh wrote Eileen as a stunt. She has said it was her cynical attempt to write a commercial thriller. Instead she produced a startlingly original noir, which was shortlisted for the Man Booker Prize. Subverting the conventional is her calling card. Her short-story collection Homesick for Another World is full of oddball characters who do and think nasty things. It’s no surprise, then, that the shit of the model-pretty narrator in My Year of Rest and Relaxation also stinks. That’s kind of the point.

Moshfegh’s protagonist is deeply unhappy. A central tension of the novel, given all her advantages, is “Why?” In between trips to her derelict psychiatrist for more pills and her corner bodega for more coffee, drop-in visits from her alcoholic frenemy Reva, and blackouts after which she must piece together the events of lost time — whom she’s , what beauty treatments she’s undergone, and whom she’s slept with — Moshfegh offers clues.

Those clues particularize a basketful of cultural maladies: the proliferation of porn and its insinuation into standards of feminine beauty and sexual performance, the veneration of image over substance, the absurdity of what’s categorized as high art (taxidermied dogs) vs. low , McFlurries and I Can’t Believe It’s Not Butter, self-help hucksterism disguised as empowerment, the medication of the American mind, the media’s numbing diet of tragedy, and the internalized self-loathing of young women. Superimposed on all this are more timeless themes. The narrator’s parents, unhappily married, died within six weeks of each other, a loss she’s not yet come to terms with. Her mother was beautiful but cold, and a thoroughly saturated alcoholic. Her father was a distant man whom she couldn’t reach even on his deathbed.

The material may be heavy, but Moshfegh’s treatment of these many themes is deft and ironic enough that they never feel didactic or obvious. In part that’s because they are filtered organically through her narrator’s consciousness. The humor is so dark that sometimes it’s hard to see at all, but it’s there, ready to poke its gremlin nose out at a funeral, an art gallery opening, and in every scene with the psychiatrist, Dr. Tuttle, who says things like, “A lot of psychic diseases get passed around in confined public spaces. I sense your mind is too porous.”

All this said, My Year of Rest and Relaxation isn’t an easy read. Writing instructors like to admonish students that repeated actions or events are to be avoided in fiction. “Write about the day when something different happens.” It’s hard to hold a reader’s attention if you describe your character’s umpteenth trip to the bodega or have her watch Harrison Ford’s Frantic three times in a row. The experience of reading My Year of Rest and Relaxation is not unlike sitting in a deer stand for hours, waiting to catch a glimpse of something other than woods. If you’re patient, a sudden deviation from the norm may offer a flash of insight or emotion. Moshfegh isn’t alone in constructing her narrative on repetitions and habits. This literary trend is evident in novels as varied as Ove Knausgaard’s My Struggle series, Ben Lerner’s 10:04, and Tom McCarthy’s Remainder, to name a few. My Year of Rest and Relaxation is different in that the protagonist is a woman whom the world would have us believe isn’t worth such minute attention. The narrator herself isn’t enamored of her own quotidian minutiae. But in attempting to avoid the bigger, more painful emotions and events in her life, they are all that she is left with.

The narrator’s emotions most often get screen time when her friend Reva appears on the scene. Addicted to revolting alcoholic concoctions (think Jose Cuevo and Diet Mountain Dew) and the perverse advice doled out in Cosmo and Marie Claire, Reva is enmeshed in an affair with her married boss and struggling with bulimia. She has the habit of showing up at the narrator’s apartment at night to drink and kvetch and declare “I love you.” “Maybe she did, and that’s why I hated her,” the narrator muses at one point. If Moshfegh’s blonde zombie has given up, Reva is still striving. The narrator’s professed feelings for Reva oscillate between apathy and contempt, but there are hints of something deeper underneath. When her friend suffers a personal tragedy, the suspense becomes whether the narrator will rally to offer Reva support—which requires her leaving the cocoon of her apartment.

Is this character likable? That question, often dismissed as the canard that distracts middle-brow book clubs from more interesting questions, deserves serious consideration in the case of My Year of Rest and Relaxation. Because Moshfegh’s treatment of her narrator is so granular, readers are invited into the intimacy of this woman’s life. Whether or not we do care about her, we want to. But Moshfegh erects deliberate barriers to our sympathy. Her narrator is a liar, feckless and sometimes casually cruel, casual about her physical advantages. She has the means to conduct an experiment on herself that most of us, with jobs, families, responsibilities, and no source of independent wealth, don’t.

But sympathy doesn’t seem to be the emotion My Year of Rest and Relaxation is after. Perhaps Moshfegh wants us to feel responsible for her creation—and responsible for a culture that makes real human connection so difficult. Her narrator seeks to remain comfortably numb because the alternative is merely fulfilling other people’s vapid expectations. She’s in search of an authenticity that continually eludes her. At one point, observing Reva speak at a funeral, she says, “Watching her take what was deep and real and painful and ruin it by expressing it with such trite precision gave me reason to think Reva was an idiot, and therefore I could discount her pain, and with it, mine.”

9/11, when it eventually arrives, holds out to the narrator the promise of experiencing authentic emotion, but any such relief surely will be temporary. A visit to the 9/11 Memorial Museum reveals that our ravenous culture has consumed this tragedy whole. Below ground in lower Manhattan, history has been commodified into an eternal, smoking present; that tragic day is divvied into a series of emblems and stories crafted from expressions of raw emotion. Yet the effect is still, unmistakably, manufactured