Shadows Over America: Matt Ruff and Victor LaValle Take on Lovecraft and Race

Spend too much time with books — particularly of the kind that indulge in the pleasures of horror and dark fantasy — and it’s hard to ignore the feeling that correspondences between the volumes on your shelves are the products of more than literary coincidence. Case in point: the day an advance copy of Matt Ruff’s Lovecraft Country — the story of African-American family pursuing occult mysteries across the landscape of segregated 1950s America — arrived our offices, we learned that Shirley Jackson Award-winner Victor LaValle was publishing The Ballad of Black Tom, a novella of sorcery and police brutality in 1920s New York that plays off of H.P. Lovecraft’s notoriously racist story “The Horror at Red Hook.” Something seriously synchronistic — if not downright magical — looked to be going on.

As the work of H.P. Lovecraft has moved from the exclusive domain of fantasy-and-horror fandom to the literary mainstream, so has growing awareness of the racism and xenophobia that figures so strong in works like “The Call of Cthulhu” and “The Shadow Over Innsmouth.” Last year it was announced that the World Fantasy Award would no longer be embodied in a bust of the Providence writer. But as Ruff and LaValle’s books testify, the presence of Lovecraft as innovator and influence is as palpable as the cosmic chills many of his tales evoke.

Luckily for us, the same eldritch forces that brought Lovecraft Country and The Ballad of Black Tom into the world at nearly the same moment seemed to be at work in our favor: Matt Ruff and Victor LaValle readily agreed to a conversation, via email, about the manifold inspirations behind their books, and the desire to find a way of “wrestling,” in LaValle’s words, with an author who has cast a long shadow over our collective dreamlife. Consider the result something like a DVD commentary track, best enjoyed after taking in the excitements of their two very different — and very satisfying — variations on a theme. The following email exchange has been lightly edited for length and continuity. — Bill Tipper

Matt Ruff: When I was reading The Ballad of Black Tom — which I really enjoyed — I described it to my wife as sort of a Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead take on Lovecraft’s “The Horror at Red Hook.” I get the appeal of retelling a Lovecraft story from the point of view of a character who wouldn’t even have had a name in the original version of the tale, but I was wondering, why “Red Hook” in particular? It’s not one of Lovecraft’s better-known stories, and even Lovecraft himself didn’t seem to like it very much. What drew you to it? The New York setting?

Matt Ruff: When I was reading The Ballad of Black Tom — which I really enjoyed — I described it to my wife as sort of a Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead take on Lovecraft’s “The Horror at Red Hook.” I get the appeal of retelling a Lovecraft story from the point of view of a character who wouldn’t even have had a name in the original version of the tale, but I was wondering, why “Red Hook” in particular? It’s not one of Lovecraft’s better-known stories, and even Lovecraft himself didn’t seem to like it very much. What drew you to it? The New York setting?

Victor LaValle: I’m going to start by making an embarrassing admission. I had to ask my wife to explain what Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead was about. I know some of Stoppard’s plays but had never seen that one. I don’t know why I felt compelled to admit that up front — I could’ve just looked it up and pretended I got it. This is the equivalent of me grinning vacantly and trying not to appear clueless.

Really, though, I had Wide Sargasso Sea in mind when I was working on The Ballad of Black Tom. In the end it’s really the same idea as the Stoppard play — Jean Rhys chooses to tell the story of Jane Eyre‘s madwoman in the attic from long before she went mad. There’s the reclamation of a character who had been dismissed but also a very clear rebuttal to the politics of the work that inspired it. I think I read Wide Sargasso Sea for the first time in graduate school and it ran through me like an electric current. I didn’t know you could do things like that: argue with masterpieces, wrestle with the greats. “The Horror at Red Hook” isn’t a masterpiece by anyone’s definition (not even — as you noted — Lovecraft’s), but it took place in New York, my hometown, and it got New York so wrong that I felt there was enough room for me to step in and move around. Once I was in there I could start to address what I saw as the bigger problems not only in that story but in the work of Lovecraft as a whole.

Really, though, I had Wide Sargasso Sea in mind when I was working on The Ballad of Black Tom. In the end it’s really the same idea as the Stoppard play — Jean Rhys chooses to tell the story of Jane Eyre‘s madwoman in the attic from long before she went mad. There’s the reclamation of a character who had been dismissed but also a very clear rebuttal to the politics of the work that inspired it. I think I read Wide Sargasso Sea for the first time in graduate school and it ran through me like an electric current. I didn’t know you could do things like that: argue with masterpieces, wrestle with the greats. “The Horror at Red Hook” isn’t a masterpiece by anyone’s definition (not even — as you noted — Lovecraft’s), but it took place in New York, my hometown, and it got New York so wrong that I felt there was enough room for me to step in and move around. Once I was in there I could start to address what I saw as the bigger problems not only in that story but in the work of Lovecraft as a whole.

This leads me to Lovecraft Country, which I tore through with great joy. The book is certainly in conversation with Lovecraft, from the title to so many notes within each story, but it hardly seems beholden to Lovecraft. I was impressed by how often you simply went off in directions that might hint at something Lovecraftian but still seemed all your own. I’m thinking of the chapter called “Jekyll in Hyde Park.” The story is about body-switching of a kind, and reminded me of Lovecraft’s “The Thing on the Doorstep,” but in all other ways you explored the real-deal political and personal consequences of a profound identity switch on a character in ways I could never imagine Lovecraft doing, or being able to do. How did you manage this balance of being inspired by Lovecraft but not beholden?

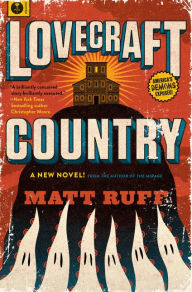

Lovecraft Country

Lovecraft Country

By Matt Ruff

Hardcover $26.99

MR: Lovecraft Country actually started out as a riff on The X-Files. The twist was, instead of white FBI agents, the protagonists would be a black family who owned a Jim Crow−era travel agency and published a “Safe Negro Travel Guide” for African-American tourists. And their paranormal adventures would combine classic genre tropes with a realistic exploration of American racism. Each character would get a chance to star in their own weird tale — a haunted house story, a Jekyll and Hyde story, a “let’s steal the Necronomicon” story — while simultaneously dealing with stuff like housing segregation and police violence and the legacy of slavery.

So it was always intended to be about more than Lovecraft — it was about genre fiction as a whole, and about history. But Lovecraft offered me a useful thematic bridge between cosmic horror and fantasy and the more mundane terrors of white supremacy. It occurred to me that the dread a Lovecraft character might feel exploring R’lyeh isn’t all that different from the dread of a black motorist passing through a sundown town after dark. In either case, you’re in a place where you don’t belong, encountering portents of doom at every turn, and even if you do escape with your life, your sanity is bound to take a hit.

Another issue I wanted to deal with was the dilemma of the black nerd: loving genre fiction when it doesn’t always love you back, and sometimes goes out of its way to exclude you. Lovecraft seemed like an apt symbol for that, too.

How would you describe your own relationship to Lovecraft as a reader? In Black Tom you’re taking him to the woodshed, but it strikes me as the kind of criticism you might not bother with if you didn’t also see value in his work. Can you read Lovecraft for pleasure, or is it more difficult than that? And do you have a favorite Lovecraft story?

MR: Lovecraft Country actually started out as a riff on The X-Files. The twist was, instead of white FBI agents, the protagonists would be a black family who owned a Jim Crow−era travel agency and published a “Safe Negro Travel Guide” for African-American tourists. And their paranormal adventures would combine classic genre tropes with a realistic exploration of American racism. Each character would get a chance to star in their own weird tale — a haunted house story, a Jekyll and Hyde story, a “let’s steal the Necronomicon” story — while simultaneously dealing with stuff like housing segregation and police violence and the legacy of slavery.

So it was always intended to be about more than Lovecraft — it was about genre fiction as a whole, and about history. But Lovecraft offered me a useful thematic bridge between cosmic horror and fantasy and the more mundane terrors of white supremacy. It occurred to me that the dread a Lovecraft character might feel exploring R’lyeh isn’t all that different from the dread of a black motorist passing through a sundown town after dark. In either case, you’re in a place where you don’t belong, encountering portents of doom at every turn, and even if you do escape with your life, your sanity is bound to take a hit.

Another issue I wanted to deal with was the dilemma of the black nerd: loving genre fiction when it doesn’t always love you back, and sometimes goes out of its way to exclude you. Lovecraft seemed like an apt symbol for that, too.

How would you describe your own relationship to Lovecraft as a reader? In Black Tom you’re taking him to the woodshed, but it strikes me as the kind of criticism you might not bother with if you didn’t also see value in his work. Can you read Lovecraft for pleasure, or is it more difficult than that? And do you have a favorite Lovecraft story?

The Ballad of Black Tom

The Ballad of Black Tom

In Stock Online

Paperback

$12.49

$13.99

VL: That makes so much sense! The X-Files but black agents, of a kind, clarifies the way you cycle through any number of family members while still returning to the central conspiracy with the Braithwhite family. Each story becomes a kind of “episode of the week” and each really did have that feel while still coming together to become one larger work by the end. I’m glad to see that it was also about genre fiction as a whole. Or to see my suspicion confirmed. When I saw “Widdershins” mentioned I couldn’t stop grinning. “The Beckoning Fair One” has to be one of my favorite ghost stories of all time.

I came to Lovecraft at a relatively young age, about ten or eleven. Being that young I think I was just naive enough to gloss over the worst of Lovecraft’s racism and general xenophobia. I don’t think I chose to consciously ignore it so much as I just couldn’t see. I needed the sunglasses from “They Live.” I guess I got them around the age of fifteen or sixteen. Then I could no longer avoid or ignore the worst of it.

But even then I can’t say I knew exactly how to wrestle with the issue. American culture, as a whole, has a pretty horrible record of racism in its depictions of non-white people. (Not to mention women, gay people — so much to choose from!) In that sense Lovecraft’s racism fit into a more general distaste, if not disgust, that America displayed (and still displays) for black folks. Whether it shows up real-world stuff like lynching and the denial of home loans to whole swaths of the population, or even something as seemingly benign as the old “black guy dies first” trope in horror movies. Why was it always us who got offed first? What did it mean that these films didn’t want any black people around? And what did it mean that I kept yearning for one of those black characters to allowed to stay? Those were the kinds of questions and concerns that remained with me and became central to Black Tom.

As for a favorite story, it’s probably “The Dunwich Horror.” I’ll admit that I never quite saw that ending — one of Lovecraft’s rare happy endings — as all that much of a triumph. The story concerns two brothers — one semi-human and one essentially inhuman — as they try to summon the Old Ones. There’s a lot more to it than that, but I read the story — even as a kid — as being about two children born into a horrible family. Are they monsters or were they made monsters? I understood they were out to do something diabolical, but I never thought they were the ones to blame.

Do you have a favorite Lovecraft story? Or is there someone else in the horror field who spoke to you even more powerfully, personally? Lovecraft offered you the thematic bridge, but did you have territories in mind that you were linking? Your book contains horror, but also science fiction, fantasy, and of course the realist writing. Were you trying to link all of them up in this one text?

MR: My favorite Lovecraft story is “At the Mountains of Madness.” All my favorite Lovecraft tropes are in there: the alien ruins hidden away in a remote wasteland, the ancient looming mountains serving as a constant reminder of human insignificance, the escalating sense of dread, and of course, the dogged explorers who refuse to turn back despite all the warning signs Lovecraft is throwing at them. It’s a violent story, too — I’m thinking in particular of the wiping out of the advance party — but almost all of the violence takes place out of view, which of course makes it even worse, having to imagine what happened.

“Mountains” also offers a rare example of Lovecraft flirting, however briefly, with a more liberal view of humanity. There’s a moment where the narrator is contemplating the deaths of this unlucky group of aliens, and he feels a sense of kinship towards them, despite the fact that they’ve killed some of his own people: “Poor Old Ones! Scientists to the last — what had they done that we would not have done in their place? God, what intelligence and persistence! . . . Radiates, vegetables, monstrosities, star-spawn — whatever they had been, they were men!” Whenever I read that, I think, Yes, H.P., even alien star-spawn can be people — keep going with that line of thought, see where else it takes you. But of course he doesn’t. Even in that moment of relative clarity, he’s careful to maintain a distinction between honorary “men” and “savages.”

To your question about linking up multiple genres, I’ve always done that. As a kid I was this weird introvert who taught himself to tell stories, and the idea that you had to pick one lane and stay in it just didn’t occur to me. One of my strongest early influences was Stephen King, who was never shy about mixing and mashing genres — in particular, combining realistic character portraits with fantastic plots.

The choice of the specific stories in Lovecraft Country was driven by a combination of personal interest and the larger needs of the novel. In the case of “Dreams of the Which House” and “Horace and the Devil Doll,” those were just horror tropes I really wanted to play with. “Abdullah’s Book” happened because if you’re going to call a novel “Lovecraft Country,” the Necronomicon’s got to be in there somewhere. “Hippolyta Disturbs the Universe” was a very Matt Ruffian answer to the question, “Why would a black woman from Chicago go poking around the Wisconsin woods in the middle of the night — and keep poking around, even after it became clear what she’d stumbled onto?” The appeal of “Jekyll in Hyde Park” should be obvious from the chapter’s first line (“New Year’s Day, Ruby woke up white,”) but it was also a useful device to let readers see what the white villains were up to when they thought no one else was watching. And “The Narrow House” was the answer to another question, “How do I get Montrose to talk about the worst night of his life, and in the process explain how he became the kind of father that he is?” There’s some serious lateral thinking involved there, but like I said, I was a weird kid.

Turning back to Black Tom: Tommy Tester’s ultimate fate is somewhat ambiguous, but I think it’s safe to say he doesn’t live happily ever after, at least by any earthly definition of that phrase. I thought it was the right ending, but I wondered if at any point you were tempted to take things in a more optimistic direction. Or would that have felt like a cheat? Also, the first half of the story is told from Tommy’s perspective, but then you switch to the viewpoint of the white detective, Malone. As a storytelling choice that made sense, but there was a part of me that really wanted to stick with Tommy, and follow him through the library doors. Did you consider doing that?

VL: “At the Mountains of Madness” is deservedly, one of the jewels in Lovecraft’s crown. I like what you say, also, about Lovecraft allowing a sense of empathy, or even identification, with the aliens. It makes sense in another way, too. That part you quoted has his narrator calling them scientists and using it as a term of admiration. That makes sense as his point of connection.

The ending of the novella changed almost at the last minute thanks to input from my editor, Ellen Datlow. She acquired the novella for Tor (after I sent it to her hoping she’d like it). In the earlier version of the story Tommy went out the window and snapped his neck on the sidewalk. That’s it, all dead. But Ellen suggested I leave things less final, in part because she thought I might like to revisit Tommy, and this world again rather than treating it like a one off. She was quite right. I’m already finding myself itchy to write another installment of the tale, though I’d come at it from a slightly different angle. I had a daydream just the other day about popping out a novella a year that followed the ongoing saga of not just Tommy, but this world I’d started populating there. Like an epic novel told serially. I don’t know if that’ll turn out, but I do have the next installment in mind.

As far as the jump from Tommy’s POV to Malone’s I couldn’t see how I might stay with Tommy after he goes through his great transformation — embraces the power that the man who initially involved him in magic, Suydam, only flirts with — and still return to the plot points from “The Horror at Red Hook.” More important, though, I worried that following Tommy through the doors, and all the cosmic wonder that came with it, might stumble into the hokey or, worse, the boring. As you said about “At the Mountains of Madness” the violence takes place out of view and that only makes the imagining worse. I thought the same might happen with the cosmic. As I saw it Tommy, essentially, becomes a demigod, at least but how to write that in a way that’s convincing? If we switched to Malone’s POV and saw only glimpses of that power, at least until the end, a reader might be more willing to swallow it.

I want to switch gears slightly here because I’d been looking through your acknowledgments page, too. (As a side note, I love acknowledgments pages. Whether they’re just lists of names that mean nothing to me or long, explanatory letters to the reader, I treat them like the liner notes that used to accompany albums and CDs.)

Anyway, I knew we were both Cornell alumni, but I didn’t know we were both former students of James Turner, too. I took a few courses in the Africana Studies department, one of them with him. I remember loving Dr. Turner’s lectures and falling behind on the long reading list by about halfway through the semester. I never got rid of the texts, though, and at least a few of them made many moves with me. I read them, piecemeal, over the next five years or so and only wished I’d been a better student then so I could’ve talked with him more while we were in the same room. You wrote that “the first seeds of inspiration [for Lovecraft Country] were planted almost thirty years ago, in conversations with Joseph Scantlebury and James Turner at Cornell University.” Would you tell me what those seeds were?

MR: Joe Scantlebury was the residence hall director at Ujamaa, the Cornell program house affiliated with the Africana Studies department. Now, I grew up in New York City, so I’d had black friends before, and I’m sure all of them had tried to clue me in to the ways in which their lives were different from mine, but Joe was the first who really got me to hear what he was saying. And it stuck.

I recall one conversation that could qualify as the inspirational Ur-moment for Lovecraft Country. I’ve always liked to take long walks so I can be alone and think, and Cornell, for me, was paradise for hiking. I used to go for these epic rambles in the farmlands surrounding the campus. And one day I was coming back and I stopped by Ujamaa to see Joe, and I told him what I’d been doing and suggested that he might enjoy hiking, too. And he kind of laughed and said, “Yeah, that sounds like fun, but I can’t go walking around in white farm country.” And I’m like, “What are you talking about? This isn’t the Deep South. We’re in New York State.” And he laughed again and said, “Yeah, Matt. We’re in New York State.” At which point I stopped and actually thought about it — thought about the people I’d see when I was out hiking. It’s true, they were all white, and a lot of them had dogs with them, or gun racks in their pick-up trucks. I never got hassled, even when my hair was long, but if I’d looked like Joe, things might have gone differently. And those back roads were awfully lonely, if you did get in trouble.

So in part because the hiking was such an essential thing for me, this made a lasting impression, and I understood in a way I hadn’t before that even though we shared the same geography, Joe and I were in a sense living in two different countries, with the borders drawn much more tightly around his.

It’s because of Joe that I ended up taking one of Professor Turner’s Africana Studies courses. You were his student too, so you know — if you were making a list of truly memorable teachers, he’d be on it. A lot of the bits of business in Lovecraft Country trace back to things I first read or heard about in Professor Turner’s class. Not just the history, but personal anecdotes. Horace’s encounter with the dice man, for example — that was based on a story Professor Turner told us.

As long as we’re discussing acknowledgments, I should include a shout-out to Pam Noles, who wrote a great essay, “Shame,” about her struggles as a black nerd. Two things in particular about that piece stayed with me: her description of watching science fiction on TV with her dad when she was little, and then, a few years later, her experience seeing Star Wars for the first time, and loving it, but also noticing that there were no black characters, and finally starting to grasp what her father had been trying to tell her about this genre she’d fallen in love with.

I’m glad Ellen Datlow talked you into keeping Tommy Tester alive. Whether you bring him back or not, it feels like a more fitting ending, having him become part of the Mythos rather than simply dying. That said, if you do end up doing more novellas in this vein, I’d be excited to read them. I’d love to see a LaValle take on “The Shadow over Innsmouth.”

In the meantime I’ve been checking out your back catalog. I started with “The Devil in Silver,” which sounded like the work closest in mood to Black Tom. There is some emotional overlap, but even though I’m not far enough along to know exactly what game you’re playing, I suspect it’s going to turn out to be a different kind of story.

VL: Ujamaa! Wow. We really did cross a few similar territories on the Cornell campus. I lived in Ujamaa during my sophomore year. It was one of the great experiences of my college life. I grew up in New York, too, in Queens, and in an incredibly ethnically mixed neighborhood, even by New York City standards. And yet I can’t say I enjoyed a political consciousness when I was young. Certainly my crew of friends came in from many nations in the world, and in many colors, but it wasn’t until I went to Cornell that I really learned how to think about the world, and its systems, within any political context. I guess that shouldn’t be so surprising, — that’s half the point of college after all.

Your friend Joe’s story resonates with me, that laugh he gave. In my case I think my political consciousness got its start in the way I came to live in Ujamaa. When I got into Cornell I found out that an old childhood friend had also been accepted and we’d agreed to room together. He and I went to different high schools and one of his friends there had also been accepted. We agreed to move in to a triple together.

We got along fine and then one day, at some point in the spring semester I returned to the room to find both my roommates home. My old friend, who is Colombian, lay on his bed. My other roommate, an Italian-American kid, was on his feet. He had a white bedsheet wrapped around his body and he’d taken some kind of white paper, taped it around to form a cone, and then cut eyeholes in the paper. In other words he’d fashioned a white hood for himself. So I walked into my dorm room and there stood one of my roommates — a guy I felt friendly toward! — dressed as a Klansman. He then raised a finger and spoke in a spooky voice, “Victor, I’m here for you!”

I stood there at the door, the handle still in my left hand, genuinely stunned. I remember looking over at my childhood friend — though Colombian he was quite fair-skinned — and he had his hand over his face, laughing with obvious embarrassment. (I like to think he’d told the other guy this was a bad idea, but who knows.) I stood there at the door for another moment and understood I couldn’t live with these two anymore. I stepped out and shut the door and went down the hall where another black student was living in a single room. He was a junior, two years older than me. I asked if I could come hang out. I didn’t talk about what happened. We just sat in the room and talked and listened to music. I applied to live in Ujamaa and moved in my sophomore year.

I tell that story, in part, because we’re talking about the moments when a bell goes off, like when you realized that you and Joe were living in two different countries. That moment in my dorm room served as a similar ringing bell for me. Of course what I knew, even then, was that those two roommates almost undoubtedly thought of the moment as a stupid prank that went too far and nothing more. I don’t think that even the kid in the Klan costume considered the real implications of the moment for me. But it was my moment of seeing into that country that existed alongside mine, opposite mine, and intentionally or not it wasn’t good for me to live there. So I put a little distance between us, and I took a few Africana courses, too!

It’s kind of you to pick up The Devil in Silver, I appreciate that. I’ve been reading your work for more than a minute now. I remember reading Fool on the Hill after I’d graduated from Cornell and started my MFA back in New York. I’ve enjoyed a whole hell of a lot of your books since then and I think you’re right in identifying that magpie thing as far as the subjects of our books go. There are so many different ways to tell a story, I can’t imagine how or why any writer could ever settle on just one.

VL: That makes so much sense! The X-Files but black agents, of a kind, clarifies the way you cycle through any number of family members while still returning to the central conspiracy with the Braithwhite family. Each story becomes a kind of “episode of the week” and each really did have that feel while still coming together to become one larger work by the end. I’m glad to see that it was also about genre fiction as a whole. Or to see my suspicion confirmed. When I saw “Widdershins” mentioned I couldn’t stop grinning. “The Beckoning Fair One” has to be one of my favorite ghost stories of all time.

I came to Lovecraft at a relatively young age, about ten or eleven. Being that young I think I was just naive enough to gloss over the worst of Lovecraft’s racism and general xenophobia. I don’t think I chose to consciously ignore it so much as I just couldn’t see. I needed the sunglasses from “They Live.” I guess I got them around the age of fifteen or sixteen. Then I could no longer avoid or ignore the worst of it.

But even then I can’t say I knew exactly how to wrestle with the issue. American culture, as a whole, has a pretty horrible record of racism in its depictions of non-white people. (Not to mention women, gay people — so much to choose from!) In that sense Lovecraft’s racism fit into a more general distaste, if not disgust, that America displayed (and still displays) for black folks. Whether it shows up real-world stuff like lynching and the denial of home loans to whole swaths of the population, or even something as seemingly benign as the old “black guy dies first” trope in horror movies. Why was it always us who got offed first? What did it mean that these films didn’t want any black people around? And what did it mean that I kept yearning for one of those black characters to allowed to stay? Those were the kinds of questions and concerns that remained with me and became central to Black Tom.

As for a favorite story, it’s probably “The Dunwich Horror.” I’ll admit that I never quite saw that ending — one of Lovecraft’s rare happy endings — as all that much of a triumph. The story concerns two brothers — one semi-human and one essentially inhuman — as they try to summon the Old Ones. There’s a lot more to it than that, but I read the story — even as a kid — as being about two children born into a horrible family. Are they monsters or were they made monsters? I understood they were out to do something diabolical, but I never thought they were the ones to blame.

Do you have a favorite Lovecraft story? Or is there someone else in the horror field who spoke to you even more powerfully, personally? Lovecraft offered you the thematic bridge, but did you have territories in mind that you were linking? Your book contains horror, but also science fiction, fantasy, and of course the realist writing. Were you trying to link all of them up in this one text?

MR: My favorite Lovecraft story is “At the Mountains of Madness.” All my favorite Lovecraft tropes are in there: the alien ruins hidden away in a remote wasteland, the ancient looming mountains serving as a constant reminder of human insignificance, the escalating sense of dread, and of course, the dogged explorers who refuse to turn back despite all the warning signs Lovecraft is throwing at them. It’s a violent story, too — I’m thinking in particular of the wiping out of the advance party — but almost all of the violence takes place out of view, which of course makes it even worse, having to imagine what happened.

“Mountains” also offers a rare example of Lovecraft flirting, however briefly, with a more liberal view of humanity. There’s a moment where the narrator is contemplating the deaths of this unlucky group of aliens, and he feels a sense of kinship towards them, despite the fact that they’ve killed some of his own people: “Poor Old Ones! Scientists to the last — what had they done that we would not have done in their place? God, what intelligence and persistence! . . . Radiates, vegetables, monstrosities, star-spawn — whatever they had been, they were men!” Whenever I read that, I think, Yes, H.P., even alien star-spawn can be people — keep going with that line of thought, see where else it takes you. But of course he doesn’t. Even in that moment of relative clarity, he’s careful to maintain a distinction between honorary “men” and “savages.”

To your question about linking up multiple genres, I’ve always done that. As a kid I was this weird introvert who taught himself to tell stories, and the idea that you had to pick one lane and stay in it just didn’t occur to me. One of my strongest early influences was Stephen King, who was never shy about mixing and mashing genres — in particular, combining realistic character portraits with fantastic plots.

The choice of the specific stories in Lovecraft Country was driven by a combination of personal interest and the larger needs of the novel. In the case of “Dreams of the Which House” and “Horace and the Devil Doll,” those were just horror tropes I really wanted to play with. “Abdullah’s Book” happened because if you’re going to call a novel “Lovecraft Country,” the Necronomicon’s got to be in there somewhere. “Hippolyta Disturbs the Universe” was a very Matt Ruffian answer to the question, “Why would a black woman from Chicago go poking around the Wisconsin woods in the middle of the night — and keep poking around, even after it became clear what she’d stumbled onto?” The appeal of “Jekyll in Hyde Park” should be obvious from the chapter’s first line (“New Year’s Day, Ruby woke up white,”) but it was also a useful device to let readers see what the white villains were up to when they thought no one else was watching. And “The Narrow House” was the answer to another question, “How do I get Montrose to talk about the worst night of his life, and in the process explain how he became the kind of father that he is?” There’s some serious lateral thinking involved there, but like I said, I was a weird kid.

Turning back to Black Tom: Tommy Tester’s ultimate fate is somewhat ambiguous, but I think it’s safe to say he doesn’t live happily ever after, at least by any earthly definition of that phrase. I thought it was the right ending, but I wondered if at any point you were tempted to take things in a more optimistic direction. Or would that have felt like a cheat? Also, the first half of the story is told from Tommy’s perspective, but then you switch to the viewpoint of the white detective, Malone. As a storytelling choice that made sense, but there was a part of me that really wanted to stick with Tommy, and follow him through the library doors. Did you consider doing that?

VL: “At the Mountains of Madness” is deservedly, one of the jewels in Lovecraft’s crown. I like what you say, also, about Lovecraft allowing a sense of empathy, or even identification, with the aliens. It makes sense in another way, too. That part you quoted has his narrator calling them scientists and using it as a term of admiration. That makes sense as his point of connection.

The ending of the novella changed almost at the last minute thanks to input from my editor, Ellen Datlow. She acquired the novella for Tor (after I sent it to her hoping she’d like it). In the earlier version of the story Tommy went out the window and snapped his neck on the sidewalk. That’s it, all dead. But Ellen suggested I leave things less final, in part because she thought I might like to revisit Tommy, and this world again rather than treating it like a one off. She was quite right. I’m already finding myself itchy to write another installment of the tale, though I’d come at it from a slightly different angle. I had a daydream just the other day about popping out a novella a year that followed the ongoing saga of not just Tommy, but this world I’d started populating there. Like an epic novel told serially. I don’t know if that’ll turn out, but I do have the next installment in mind.

As far as the jump from Tommy’s POV to Malone’s I couldn’t see how I might stay with Tommy after he goes through his great transformation — embraces the power that the man who initially involved him in magic, Suydam, only flirts with — and still return to the plot points from “The Horror at Red Hook.” More important, though, I worried that following Tommy through the doors, and all the cosmic wonder that came with it, might stumble into the hokey or, worse, the boring. As you said about “At the Mountains of Madness” the violence takes place out of view and that only makes the imagining worse. I thought the same might happen with the cosmic. As I saw it Tommy, essentially, becomes a demigod, at least but how to write that in a way that’s convincing? If we switched to Malone’s POV and saw only glimpses of that power, at least until the end, a reader might be more willing to swallow it.

I want to switch gears slightly here because I’d been looking through your acknowledgments page, too. (As a side note, I love acknowledgments pages. Whether they’re just lists of names that mean nothing to me or long, explanatory letters to the reader, I treat them like the liner notes that used to accompany albums and CDs.)

Anyway, I knew we were both Cornell alumni, but I didn’t know we were both former students of James Turner, too. I took a few courses in the Africana Studies department, one of them with him. I remember loving Dr. Turner’s lectures and falling behind on the long reading list by about halfway through the semester. I never got rid of the texts, though, and at least a few of them made many moves with me. I read them, piecemeal, over the next five years or so and only wished I’d been a better student then so I could’ve talked with him more while we were in the same room. You wrote that “the first seeds of inspiration [for Lovecraft Country] were planted almost thirty years ago, in conversations with Joseph Scantlebury and James Turner at Cornell University.” Would you tell me what those seeds were?

MR: Joe Scantlebury was the residence hall director at Ujamaa, the Cornell program house affiliated with the Africana Studies department. Now, I grew up in New York City, so I’d had black friends before, and I’m sure all of them had tried to clue me in to the ways in which their lives were different from mine, but Joe was the first who really got me to hear what he was saying. And it stuck.

I recall one conversation that could qualify as the inspirational Ur-moment for Lovecraft Country. I’ve always liked to take long walks so I can be alone and think, and Cornell, for me, was paradise for hiking. I used to go for these epic rambles in the farmlands surrounding the campus. And one day I was coming back and I stopped by Ujamaa to see Joe, and I told him what I’d been doing and suggested that he might enjoy hiking, too. And he kind of laughed and said, “Yeah, that sounds like fun, but I can’t go walking around in white farm country.” And I’m like, “What are you talking about? This isn’t the Deep South. We’re in New York State.” And he laughed again and said, “Yeah, Matt. We’re in New York State.” At which point I stopped and actually thought about it — thought about the people I’d see when I was out hiking. It’s true, they were all white, and a lot of them had dogs with them, or gun racks in their pick-up trucks. I never got hassled, even when my hair was long, but if I’d looked like Joe, things might have gone differently. And those back roads were awfully lonely, if you did get in trouble.

So in part because the hiking was such an essential thing for me, this made a lasting impression, and I understood in a way I hadn’t before that even though we shared the same geography, Joe and I were in a sense living in two different countries, with the borders drawn much more tightly around his.

It’s because of Joe that I ended up taking one of Professor Turner’s Africana Studies courses. You were his student too, so you know — if you were making a list of truly memorable teachers, he’d be on it. A lot of the bits of business in Lovecraft Country trace back to things I first read or heard about in Professor Turner’s class. Not just the history, but personal anecdotes. Horace’s encounter with the dice man, for example — that was based on a story Professor Turner told us.

As long as we’re discussing acknowledgments, I should include a shout-out to Pam Noles, who wrote a great essay, “Shame,” about her struggles as a black nerd. Two things in particular about that piece stayed with me: her description of watching science fiction on TV with her dad when she was little, and then, a few years later, her experience seeing Star Wars for the first time, and loving it, but also noticing that there were no black characters, and finally starting to grasp what her father had been trying to tell her about this genre she’d fallen in love with.

I’m glad Ellen Datlow talked you into keeping Tommy Tester alive. Whether you bring him back or not, it feels like a more fitting ending, having him become part of the Mythos rather than simply dying. That said, if you do end up doing more novellas in this vein, I’d be excited to read them. I’d love to see a LaValle take on “The Shadow over Innsmouth.”

In the meantime I’ve been checking out your back catalog. I started with “The Devil in Silver,” which sounded like the work closest in mood to Black Tom. There is some emotional overlap, but even though I’m not far enough along to know exactly what game you’re playing, I suspect it’s going to turn out to be a different kind of story.

VL: Ujamaa! Wow. We really did cross a few similar territories on the Cornell campus. I lived in Ujamaa during my sophomore year. It was one of the great experiences of my college life. I grew up in New York, too, in Queens, and in an incredibly ethnically mixed neighborhood, even by New York City standards. And yet I can’t say I enjoyed a political consciousness when I was young. Certainly my crew of friends came in from many nations in the world, and in many colors, but it wasn’t until I went to Cornell that I really learned how to think about the world, and its systems, within any political context. I guess that shouldn’t be so surprising, — that’s half the point of college after all.

Your friend Joe’s story resonates with me, that laugh he gave. In my case I think my political consciousness got its start in the way I came to live in Ujamaa. When I got into Cornell I found out that an old childhood friend had also been accepted and we’d agreed to room together. He and I went to different high schools and one of his friends there had also been accepted. We agreed to move in to a triple together.

We got along fine and then one day, at some point in the spring semester I returned to the room to find both my roommates home. My old friend, who is Colombian, lay on his bed. My other roommate, an Italian-American kid, was on his feet. He had a white bedsheet wrapped around his body and he’d taken some kind of white paper, taped it around to form a cone, and then cut eyeholes in the paper. In other words he’d fashioned a white hood for himself. So I walked into my dorm room and there stood one of my roommates — a guy I felt friendly toward! — dressed as a Klansman. He then raised a finger and spoke in a spooky voice, “Victor, I’m here for you!”

I stood there at the door, the handle still in my left hand, genuinely stunned. I remember looking over at my childhood friend — though Colombian he was quite fair-skinned — and he had his hand over his face, laughing with obvious embarrassment. (I like to think he’d told the other guy this was a bad idea, but who knows.) I stood there at the door for another moment and understood I couldn’t live with these two anymore. I stepped out and shut the door and went down the hall where another black student was living in a single room. He was a junior, two years older than me. I asked if I could come hang out. I didn’t talk about what happened. We just sat in the room and talked and listened to music. I applied to live in Ujamaa and moved in my sophomore year.

I tell that story, in part, because we’re talking about the moments when a bell goes off, like when you realized that you and Joe were living in two different countries. That moment in my dorm room served as a similar ringing bell for me. Of course what I knew, even then, was that those two roommates almost undoubtedly thought of the moment as a stupid prank that went too far and nothing more. I don’t think that even the kid in the Klan costume considered the real implications of the moment for me. But it was my moment of seeing into that country that existed alongside mine, opposite mine, and intentionally or not it wasn’t good for me to live there. So I put a little distance between us, and I took a few Africana courses, too!

It’s kind of you to pick up The Devil in Silver, I appreciate that. I’ve been reading your work for more than a minute now. I remember reading Fool on the Hill after I’d graduated from Cornell and started my MFA back in New York. I’ve enjoyed a whole hell of a lot of your books since then and I think you’re right in identifying that magpie thing as far as the subjects of our books go. There are so many different ways to tell a story, I can’t imagine how or why any writer could ever settle on just one.