This illustration shows what the newly identified horned dinosaur Xenoceratops foremostensis may have looked like. While the horns and spikes on the dinosaur's head are accurate depictions based on fossils, the color of its hide is speculative. "We know that color patterns are important for recognition and mate choice," said Cleveland Museum of Natural History paleontologist Michael Ryan. "If you look at the related lizards and snakes, they can be highly colored." For dinosaurs, "what we try to do is come up with a plausible color scheme that looks good aesthetically."

This illustration shows what the newly identified horned dinosaur Xenoceratops foremostensis may have looked like. While the horns and spikes on the dinosaur's head are accurate depictions based on fossils, the color of its hide is speculative. "We know that color patterns are important for recognition and mate choice," said Cleveland Museum of Natural History paleontologist Michael Ryan. "If you look at the related lizards and snakes, they can be highly colored." For dinosaurs, "what we try to do is come up with a plausible color scheme that looks good aesthetically." Identifying a new dinosaur is as much about detective work as digging up fossils. Ancient bones don't come with labels naming the animal they belonged to. Figuring out what you've got involves piecing together subtle clues, spotting patterns of evidence, doggedly pursuing leads, and following hunches.

So when Cleveland Museum of Natural History paleontologist Michael Ryan tugged open a storeroom drawer in Ottawa's Canadian Museum of Nature a few years ago, he knew the detective hunt was on.

Inside was a bony, triangular spike, about 8 inches long, missing its pointed tip. In an adjacent drawer was a curved chunk of bone with a socket that probably had housed a wicked spike like the one in the nearby compartment.

A scientist had unearthed the specimens in western Canada in 1958, but never determined what they were. Ryan, a horned dinosaur expert, suspected the fossils were from a broad group of horned dinosaurs called ceratopsians, whose members include the well-known, tank-sized Triceratops. But they didn't resemble anything he'd seen before, and there wasn't enough material to make a positive ID.

How Ryan and his colleagues eventually deciphered the contents of those dusty drawers is a story of gumshoe persistence, keen instincts and luck. The outcome, announced this month, is a newly identified kind of horned dinosaur the researchers dubbed Xenoceratops (pronounced ZEE-no-seer-ah-tops) foremostensis.

A shallow inland sea bisected North America during the Late Cretaceous epoch.

A shallow inland sea bisected North America during the Late Cretaceous epoch. The 78 million-year-old animal, about the size of a big bull, is the oldest known large-bodied horned dinosaur yet found in Canada. Scientists say Xenoceratops' unique, fearsome-looking array of spikes, knobs and hooks further illustrates the extraordinary diversity of these dinosaurs, which spun off new species as fast as every 200,000 years. The discovery may help researchers better understand the evolutionary forces driving that variety.

"It's a very significant find," said paleontologist Mark Loewen of the Natural History Museum of Utah, who wasn't involved in the effort.

The bones in the drawer were dug up by now-renowned paleontologist Wann Langston Jr., who, early in his career, spent time hunting dinosaur fossils in western Canada.

That region was the bulls-eye for a startling explosion of dinosaur forms during much of the Late Cretaceous epoch, between 95 million and 68 million years ago. A shallow inland seaway stretched from the Arctic Ocean to the Gulf of Mexico, splitting North America in half. The western landmass, called Laramidia, was a "crucible of evolution" for dinosaurs, Loewen and colleagues wrote in a 2010 study.

That was especially true for the large-bodied horned dinosaurs, whose ancestors probably had entered North America by crossing a temporary land bridge from Asia.

Hemmed in on a relatively narrow strip of land by the newly rising Rocky Mountains on one side and the waxing and waning seaway's shoreline on the other, the horned dinosaurs responded to changing conditions by developing an astounding assortment of horns, hooks, fins and other shapes that sprouted from the bony collar, or frill, at the back of their skulls.

Each species had its own distinctive selection and arrangement of those ornamental protrusions, which marked the dinosaur like a football uniform identifies a team.

In closeup, this illustration shows the bony collar, or frill, at the back of Xenoceratops' skull, and the distinctive array of spikes, horns and fins that make it unique and differentiate it from other species. Xenoceratops' sharp beak was used for snipping off low-hanging vegetation for the plant-eater to chew.

In closeup, this illustration shows the bony collar, or frill, at the back of Xenoceratops' skull, and the distinctive array of spikes, horns and fins that make it unique and differentiate it from other species. Xenoceratops' sharp beak was used for snipping off low-hanging vegetation for the plant-eater to chew. Though the bony arrays looked menacing, researchers think their purpose was largely ornamental, helping the lumbering plant-eaters recognize others of their kind, identify rivals and attract potential mates. Horned dinosaurs' fossilized skulls show they had large eye sockets and big optic nerves, indicating their vision was easily sharp enough to distinguish bony display patterns and other visual cues from a distance.

"These were spectacular animals, not just in size but shape and probably color as well," said Hans Sues, curator of vertebrate paleontology at the National Museum of Natural History. "If you have a nice set of spikes, that might say to your rival, 'Don't mess with this guy. This is a vigorous individual. Pick on someone else.' " For a potential mate, "she might say, 'Wow, he has a nice frill. Let's hang out with this guy.' "

The inland sea's periodically shifting coastline isolated individual populations of horned dinosaurs, setting up the opportunity for variations as evolution ran its course on each group.

"They change by mate preference, so maybe the females [in one group] are preferring a little bit longer horn or something like that," Loewen said. "That small population is able to change relatively quickly. And then when the [shoreline] barriers go away, they mix with the first population that's maybe gone in a different direction. One of the two groups goes extinct, and you get replacement in the fossil record."

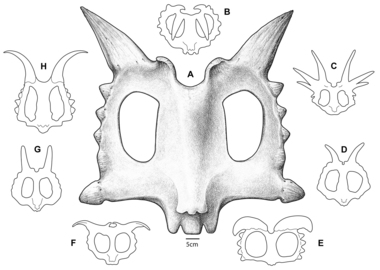

This illustration shows how the bony ornamental collar, or frill, and horns of Xenoceratops foremostensis, center, compare to the frill and horn patterns of other horned dinosaurs of the Centrosaurine family.

This illustration shows how the bony ornamental collar, or frill, and horns of Xenoceratops foremostensis, center, compare to the frill and horn patterns of other horned dinosaurs of the Centrosaurine family. Though researchers have been uncovering horned dinosaur fossils for about a century, they've learned a lot more about them in last two decades. Ryan has been a prominent figure in that process, identifying 10 new species. Much of that work involves spending time in the field, "walking the rocks" in the fossil-rich areas of southern Alberta, in Ryan's native Canada.

But when he isn't plucking dinosaur bones from rocky outcrops in the western Canadian badlands, Ryan and his research partner, Royal Ontario Museum paleontologist David Evans, scour museum storerooms. They're "hoovering up all the information we can," Ryan said, looking for fossils that others previously dug up in the same area, for comparison.

That's how he came upon the drawers holding Wann Langston's unidentified dinosaur spike and frill fragment from 1958.

In this 2007 photo, Cleveland Museum of Natural History scientist Michael Ryan shows the skull fragments of a newly identified horned dinosaur called Albertaceratops nesmoi.

In this 2007 photo, Cleveland Museum of Natural History scientist Michael Ryan shows the skull fragments of a newly identified horned dinosaur called Albertaceratops nesmoi. Langston, who's still alive and a practicing scientist, had recovered the bones in a place Ryan knew, a layering of ancient rocks called the Foremost Formation. At various times in the past, the area had been both covered and uncovered by the inland sea. The exposed rock layer that contained the dinosaur bones Langston found was roughly 78 million years old – older by a half-million years than the then-oldest Canadian horned dinosaur, Albertaceratops, which Ryan identified in 2007.

To Ryan, Langston's fossils were both familiar and not.

"Intuitively you know what this stuff is," he said, "but it looks so strange compared to what's previously known that we couldn't make it fit our paradigm. I puzzled over them but didn't do a lot with them."

Ryan filed away the memory, but it kept nagging him and Evans. "We'd always go back to that one drawer and pull it open and try to figure out what the heck that stuff was," Ryan said.

Several years passed. Finally, while reading the old field notes Langston had written during his Foremost Foundation dig, Evans spied a crucial bit of information.

When researchers working in remote spots find interesting fossils, they excavate the rock that contains them and wrap the chunk in plaster-soaked burlap for protection during transport. The encasement is called a "field jacket." Back at the museum, field jackets with promising contents are carefully cracked open and their fossils cleaned and prepared for study.

Langston's notes said he'd brought back three field jackets from the Foremost dig. But the spike and frill piece in the museum drawer weren't enough to constitute three field jackets. There must be others somewhere.

The Ottawa museum "has a long Indiana Jones-like hall full of unopened field jackets," Ryan said. Evans and the museum's collections manager located two from Langston's 1958 expedition. Evans borrowed them and took them to the Royal Ontario Museum in Toronto where he works.

Skull fragments of the newly identified horned dinosaur Xenoceratops foremostensis have been carefully pieced together at the Canadian Museum of Nature in Ottawa. The fragments actually come from at least three separate dinosaurs.

Skull fragments of the newly identified horned dinosaur Xenoceratops foremostensis have been carefully pieced together at the Canadian Museum of Nature in Ottawa. The fragments actually come from at least three separate dinosaurs. Inside was paydirt – enough pieces of dinosaur bone to make up the back and sides of a frill, as well as parts of the face and cheek. The pieces came from at least three individual horned dinosaurs, whose remains had mingled in a "bone bed."

Together with the spike and frill fragment from the drawer, the features of the animals were unique enough to convince Ryan and Evans that they'd found something new. They named the dinosaur Xenoceratops, which translates as "alien horned-face," and foremostensis, for the village of Foremost near the dig site.

In addition to the arm-length spikes at the top of its frill, Xenoceratops had big brow horns above each eye. And between the frill spikes were two downward-pointing flaps of bone – "droopy, dog ear-like things," Ryan said – that were further ornamentation.

Other horned dinosaurs traveled in herds, judging by the massive fossil graveyards that researchers have discovered when the animals suddenly died. "The fact that we found three individuals associated with one another . . . suggests that maybe Xenoceratops was doing the same thing," Ryan said.

The environment Xenoceratops lived in was sub-tropical, with low, flat plains and deltas dotted by shrubs and giant, sequoia-like trees. The dinosaurs' squat, four-legged bodies meant they were only able to reach low-hanging vegetation. Their beak-like mouths, resembling a giant parrot's, suggest they ate a fairly woody diet, snipping off small saplings.

The large size of Xenoceratops' spikes indicates that there must be older, as-yet undiscovered ancestors with smaller projections.

"It means we're missing a whole bunch of evolutionary specimens, because we know that you had to go from something without a horn to a [big] horn," Ryan said. There had to be intermediate forms.

A sister group of horned dinosaurs called Zuniceratops, 10 million years older than Xenoceratops, also had giant horns, Ryan said. That means scientists must look even deeper in the past for evolutionary predecessors – a tough prospect since there are few places where rocks that old are exposed for fossil-hunting.

While Ryan said the identification of a new dinosaur is rewarding – whether from a fossil dug up in the badlands or found in a museum drawer – he and Evans are after bigger game. They want to pin down in even greater detail how environment and evolution were interacting to affect the speed at which new horned dinosaur species appeared.

"Museums love to put new dinosaurs on display, and I love to write papers about them, but that's not the alpha reason we're doing this," Ryan said. "We've got a couple of really cool papers we're working on right now. We're getting good data from our results that are answering really big questions."