Methods for all moments

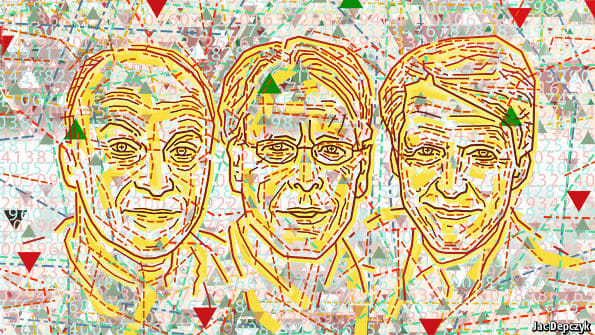

The Nobel prize in economics reveals how little we know about the behaviour of markets

THE “prize in economic sciences in memory of Alfred Nobel”, as it is officially known, sometimes struggles to command the same respect as its counterparts. Though awarded by the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, just like the prizes in physics, chemistry and medicine, it was a latecomer to the ceremonies, established in 1968 by Sweden’s central bank rather than in 1896 by Mr Nobel’s will. This year’s winners appeared to reinforce doubts about the prize’s standing. One, Eugene Fama of Chicago, is known for his ardent belief in the efficiency of markets: he declined to renew his subscription to this newspaper after tiring of its incessant warning about bubbles, the very existence of which he denies. Robert Shiller from Yale, in contrast, is known for his prescient warnings of bubbles, in technology stocks in the 1990s and in housing in the 2000s.

This article appeared in the Finance & economics section of the print edition under the headline “Methods for all moments”

More from Finance & economics

Europe’s economic growth is extremely fragile

Risk is concentrated in one country: Germany

How vulnerable is Israel to sanctions?

So far, measures have had little effect. That could change

Why companies get inflation wrong

Bosses should pay less attention to the media

What is behind China’s perplexing bond-market intervention?

The central bank seems to think the government’s debt is too popular

How to invest in chaotic markets

Contrary to popular wisdom, even retail investors should pay attention to volatility

Vladimir Putin spends big—and sends Russia’s economy soaring

How long can the party last?