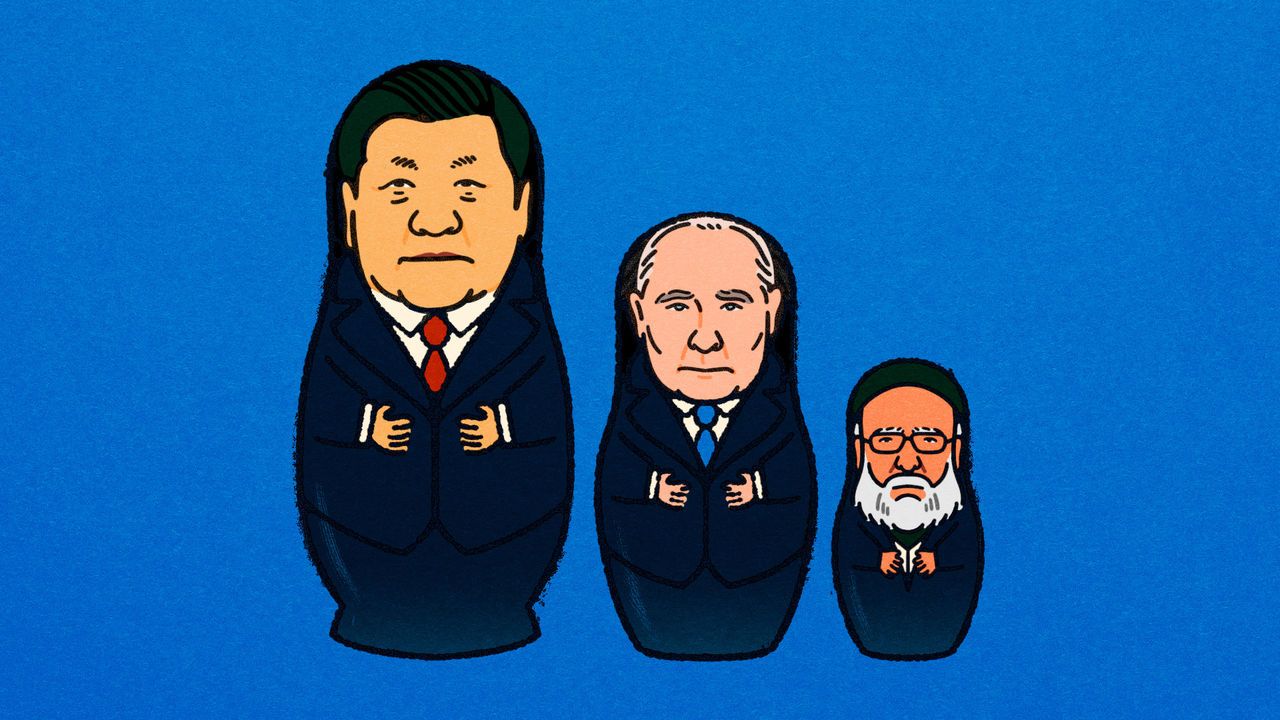

How China, Russia and Iran are forging closer ties

Assessing the economic threat posed by the anti-Western axis

Vladimir Putin, Russia’s president, and Ebrahim Raisi, his Iranian counterpart, have several things in common. Both belong to a tiny group of leaders personally targeted by American sanctions. Even though neither travels much, both have been to China in recent years. And both seem increasingly fond of one another. In December they met in the Kremlin to discuss the war in Gaza. On March 18th Mr Raisi was quick to congratulate Mr Putin on his “decisive” election victory.

For much of history, Russia, Iran and China were less chummy. Imperialists at heart, they often meddled in one another’s neighbourhoods and jostled for control of Asia’s trade routes. Lately, however, America has changed the dynamic. In 2020, two years after exiting a deal limiting Iran’s nuclear programme, it reimposed a trade embargo on the country; more penalties were announced in January, to punish Iran for backing Hamas and Houthi rebels. Russia fell under Western sanctions in 2022, after invading Ukraine, which were recently tightened. Meanwhile, China faces restrictions of its own, which could become much more stringent if Donald Trump is elected president in November. United by a common foe, the trio now vow to advance a common foreign policy: support for a multipolar world no longer dominated by America. All see stronger economic ties as the basis for their alliance.

China has promised a “no limits” partnership with Russia, and signed a 25-year “strategic agreement” with Iran in 2021. All three countries are members of the same multilateral clubs, such as the BRICS. Bilateral trade is growing; plans are being drawn up for tariff-free blocs, new payment systems and trade routes that bypass Western-controlled places. For America and its allies, this is the stuff of nightmares. A thriving anti-Western axis could dodge sanctions, win wars and recruit other malign actors. The entente involves areas where links are already strong, others where collaboration is only partial and some unresolved questions. What might the alliance look like in five to ten years?

Explore more

This article appeared in the Finance & economics section of the print edition under the headline “The anti-Western axis”

Finance & economics March 23rd 2024

- How China, Russia and Iran are forging closer ties

- Japan ends the world’s greatest monetary-policy experiment

- Why America can’t escape inflation worries

- First Steven Mnuchin bought into NYCB, now he wants TikTok

- America’s realtor racket is alive and kicking

- How to trade an election

- Why “Freakonomics” failed to transform economics

More from Finance and economics

Why Chinese banks are now vanishing

The state is struggling to deal with troubled institutions

How Starbucks caffeinates local economies

Call it the frappuccino effect

How much cash should be removed from the financial system?

Undoing quantitative easing provokes fierce debate