Kate Quinn Dishes on the Recipe for a Perfect Historical Novel

Posted by Cybil on July 2, 2024

Grace March arrives at Briarwood House with a suitcase, sun tea, and a sensibility that makes strangers feel like family.

The most recent addition to the boardinghouse, Grace rents a closet-size room in the attic, with little more than a hot plate for hospitality. But no matter. Her warmth quickly spreads to every corner of the house, like the vine that she paints on the wall of her room, thanks to the weekly supper club that she starts for the disparate crew of women who live there.

Who could guess that mystery and a double murder would be on the menu?

The Briar Club, Kate Quinn’s latest novel, weaves history, mystery, and murder into life in America and Washington, D.C., in the 1950s. A seemingly idyllic period for the country, Quinn uses the stories of these seven women to shed more light on the past.

She spoke to Goodreads contributor April Umminger about her lifetime of writing, recipes for hot plates, and finding inspiration in obscure historical events. Their conversation has been edited.

The most recent addition to the boardinghouse, Grace rents a closet-size room in the attic, with little more than a hot plate for hospitality. But no matter. Her warmth quickly spreads to every corner of the house, like the vine that she paints on the wall of her room, thanks to the weekly supper club that she starts for the disparate crew of women who live there.

Who could guess that mystery and a double murder would be on the menu?

The Briar Club, Kate Quinn’s latest novel, weaves history, mystery, and murder into life in America and Washington, D.C., in the 1950s. A seemingly idyllic period for the country, Quinn uses the stories of these seven women to shed more light on the past.

She spoke to Goodreads contributor April Umminger about her lifetime of writing, recipes for hot plates, and finding inspiration in obscure historical events. Their conversation has been edited.

Goodreads: First off, how did you start writing?

Kate Quinn: I grew up very young with a big love of story.

I was lucky enough to be raised by a mom who was not only a librarian but had a degree in ancient and medieval history. I was learning about history in the same sort of casual way that my friends were absorbing Saturday morning cartoons. I was also fortunate that both my mom and my dad read to me.

I did my first short story when I was seven, and it was front and back on a sheet of typing paper, with a pencil. I completed my first novel when I was 10 when I had learned to type, and it was 121 double-spaced pages of pure awful that live under the bed and will never, ever come out.

It did mean that pretty much from that time, I was never without a book that I was working on. It's just something that I did, and from a young age, is something I love. And I know that, honestly, if I was not lucky enough to be able to do this for a career, I would still be doing it.

I would just be putting books in drawers when I was done with them, rather than sending them off to an editor.

GR: So ever since you were seven years old, you’ve always been working on a book? That is incredible!

KQ: Pretty much. It has just been my constant thing. Sometimes if I have gotten a little blocked, I feel antsy and annoyed and unhappy until I get something else going again. I always have stories going on in some way, shape, or form.

GR: What's the most fun part for you with writing historical fiction?

KQ: I love it because, honestly, until a time machine or TARDIS are invented or come along, historical fiction is about the closest we can get to time travel.

I love good historical fiction for that reason. It takes us into worlds that are very different from our own and shows us stories from eyes that are very different from our own lived, personal experience.

It's not only a way to time travel, but also a way to look and gain empathy into the issues of the past. That's the real value of historical fiction—it has that ability to make us consider things from different angles.

I think historical fiction and science fiction, they're a little bit sister genres. Science fiction has always been notorious for looking at the issues of the present through the lens of the future, and historical fiction does the same thing. It looks at the issues of the present through the lens of the past.

This book is about the 1950s, and yet so many of the problems that the women in this book are facing are problems that are still being discussed and worked out and worked through today.

GR: How do you get your ideas for your books?

KQ: Walmart, aisle seven. That's, that's the absolute truth.

GR: [Laughs.] My gosh, Walmart's gonna love you.

KQ: I tend to have ideas that go off in my head all the time. And I think all writers do—it is a matter of What is the thing that lights you up inside?

That's the fun part; you could show 100 different writers 100 different interesting snippets, and we'd all get lit up by something different. I think we cannot choose what we're fascinated by.

I know that I happen to be fascinated by the way in which women of the past carve out these little spheres of influence and independence and power for themselves when they live in eras that do not want them to have it. That is what lights me up—woman or a group of women who've done something truly extraordinary that make me think, “Wow, I wish I knew more about this. Why didn't I know about this growing up?”

That usually is what will kick me off toward whatever my next book will be.

So, it’s less about Walmart, aisle seven. I wish there was somewhere concrete that we could go to find that new idea, because you just never know when something is going to light you up. It's a very mysterious process.

GR: Along those lines, how did the plot come together?

KQ: I wanted to use each woman as a filter or a lens for a different aspect of life in this time period. It was also a way to examine the idea What are the American ideals of the time, and how did those ideals play out in real life?

Nora, for example, I used her to examine the legal issues of crime versus punishment, and organized crime and the mob versus police corruption during the day.

Reka, who is the older woman who was a refugee from Berlin in the ’30s, she's a way to examine this hangover from World War II and how that is not necessarily over for everybody involved, no matter how everybody wants to put the war in their rearview mirror. It's also a way to look at what it is like for refugees who have managed to make their way out of a terrible past into what's supposed to be the bright new world, but how does that bright new world really look?

For Fliss, it was looking at the Korean War because her husband is a doctor in Korea, and it is looking at motherhood and what does that look like in the ’50s? It's also a way to look at the development of the birth control pill, which was a big thing that was coming out.

For Claire's story, it was Capitol Hill, and Washington, D.C., and the movers and shakers in there with McCarthy, and the fact that she works for Margaret Chase Smith, who was the senator from Maine who was the only senator who had the nerve to stand up on the Senate floor and challenge McCarthy and say, “This is not what America is about.”

All these women were different ways of looking at different things. I had lists of things I wanted to include in the book, and then it was a matter of trying to figure out which woman would most organically fit that particular piece of history, as part of her story. Once I had that figured out, and in what order, it was a matter of tackling each one sequentially.

GR: Oh, that's great. Another thing I found period appropriate and different is that each woman had a signature recipe with an accompanying jazz song. It seemed very 1950s. Have you cooked all the recipes, and why include them?

KQ: I wanted to have recipes because the way that these women get to know each other is that there starts to be a weekly supper club. They take turns cooking, and they're very limited in what they can cook because they're all pretty broke and the only kitchenette equipment that they have is a hot plate on a mini fridge.

But they do their best, because that's what feeding your friends is and you don't have to be a gourmet chef.

Now, I'm lucky enough to more or less have a gourmet chef in my house for a test kitchen. My husband is active-duty navy and is also a sensational cook. He's half Sicilian, and his mom and grandma were teaching him how to make a red sauce from scratch at four years old, that kind of thing.

Books and food have always been woven together for us since we were in college together, where we started a tradition that we literally carry on to this day. He cooks dinner, and I sit at the counter, and I read aloud from whatever book that I think we would both enjoy.

We have cooked all these recipes. These are all things that have shown up at Chez Quinn at some point, while I've been reading in background, and my husband has developed all these recipes. They're all delicious. They can all be done on a hot plate or burner, or just a stovetop with one or two exceptions.

I wanted there to be a real melting pot of food. Pete, who is of Swedish descent, has Swedish meatballs as his contribution. There is a Ukrainian character who has a signature Ukrainian dish, that I did get from a Ukrainian food blogger.

Bea, the Italian and the ex-baseball player from the All-American Girls Professional Baseball League, she's from Boston's North End, so she has a proper Italian red sauce, which absolutely comes from my husband.

The food was a way to demonstrate the melting pot that America is. The vast variety of recipes that have made their way into American cuisine, to some degree, become Americanized. What is authentic American food? I'm not sure anybody can answer that.

I threw the songs in there, too, because songs and music are such a great way to encapsulate an era. For every point in the book when I had a recipe, I was thinking, “OK, what was a chart-topping song at that time?”

But there's truly weird cuisine from the 1950s. I do not understand this urge to suspend things in Jello that should never have been in contact with Jello. I did put one very funny recipe in there that is a real ’50s recipe that I don't think I would ever eat in person, but it was so funny I couldn't not put it in there. That is something called candle salad.

GR: Ooooh, yeah. [Laughs.]

KQ: I'm not going to say anything more about candle salad, except Google a picture of it and try not to laugh your head off.

GR: You give the house a voice in the novel. It's somewhat unexpected for historical fiction. Is this something you've done before? How did you decide to make the house a character?

KQ: I always believed that places can very much have personalities. And since this book is so firmly tied to the theme of what makes a house into a home, it seemed natural to give the house a quite literal personality.

The frame of this book involves the unfolding investigation of a murder within the house, and originally it was told from the point of view of the detective who was on duty.

But honestly, police procedural stuff bores me, and I realized I wasn't really interested in the detective as a person. I ended up putting all those framing scenes into the point of view of the house itself, as it comments on the murder drama and investigation unfolding within its walls, because the house is very much invested for the outcome of the people who live inside.

As soon as I had that, I thought that's what's going to make this really sing.

GR: I read your historical note in the book, so I’ve got a general idea, but where did you get the idea for The Briar Club?

KQ: My attention fell on the 1950s because I've always found it an interesting decade. It seemed by many as an idyllic—or boring or repressive, depending on whom you ask—period of peace and domesticity between the very war-driven upheaval of the 1940s and the social and civic upheaval of the 1960s.

But as with most outwardly peaceful periods of history, there is a lot going on under the surface. The hangover from World War II is far from over, and the desire for social change is coming to a boil, even if its effects are not going to be seen for a few years.

America was taking the lead during that decade, where so much of the rest of the world was rebuilding from war, and very eager to lead in everything from scientific advancement to the space race, but still backward in many ways.

Segregation and racism was rampant, women being hamstrung in the workplace and pushed into the feminine ideal of the ’50s housewife, there was so much anti-communist fervor leading to witch hunts where innocent people's lives were destroyed because of what they believed or who they knew.

It was lots and lots of grist for a story, and that was one of the things that really kicked me off.

GR: Just thinking about the 1950s as idyllic—the juxtaposition of the American dream with the Red Scare, the cementing of the nuclear family and with the advent of the birth control pill, peacetime but there was still war in Korea—were you trying to say something bigger about America or just explore the nuances of the 1950s?

KQ: I wanted to look at the 1950s through the microcosm of this group of women—all very different women—whose lives could be used as a different lens, each one to examine a different issue that was going on in women's lives in the ’50s, and specifically in America.

It also was my own way of examining the questions of what it is to be an American. What is the American dream? Who gets it? Who is entitled to it? How do you achieve it? Who gets a chance at it?

Being an American feels like a complicated thing right now. How do you take pride in our country without airbrushing away its mistakes? How to remember and acknowledge and honor our legacy while not whitewashing our past sins?

Historical fiction is a great way to have a warts-and-all approach to the past. It's a way where we can look at the good alongside the bad, do not elevate the one above the other, learn from both.

The Briar Club is very much a book about what it is to be an American, which is something that the past decade of political upheaval and social unrest has us all pondering, with what feels sometimes like increasing desperation.

GR: You also mentioned in your historical note that this was the book you wrote coming out of the pandemic. When did you start to write it, and how long did it take to finish?

KQ: I think that most writers have a pandemic book, the book that into which we poured all of our dark and desperate and complicated feelings about the pandemic and the lockdown.

But I think of this as my post-pandemic novel. I got the idea in mid 2021, and lockdown was starting to end where I was, and the world was reopening a little bit. There are vaccines and things are starting to look a little more hopeful in some ways.

When I was in lockdown, and I was not able to see my friends for a long time, and there's a lovely food essay that I adore called “Alone in the Kitchen with an Eggplant” from the wonderful food writer Laurie Colwin. She wrote with so much humor and heart about her years as a broke twentysomething, living in a broom closet–size apartment in New York City, and how she managed to feed her equally broke friends from a kitchenette that consisted of a mini fridge, a hot plate, and a dish rack that was parked in the bathtub.

I reread that essay a lot during the pandemic, whimpering [laughs] because I would cook on a hot plate and drain spaghetti in my bathtub if I could just be surrounded by loved ones and friends and scraped plates and half empty bottles of wine.

That had me thinking, Could this be a book? You know, stranger comes to town, pulls housemates together with weekly dinners in her tiny apartment…that was one of the things that really was a spur for this novel. Honestly, the fact that I missed community, I missed dinner parties, I missed my friends.

GR: How long did this take you to write, and what was your process?

KQ: It's a little hard to tell with this book how long it took. I began it and was about 40,000 words into it, and then I ended up selling another novel that became The Phoenix Crown, which is a coauthored novel with my lovely friend and colleague, Janie Chang. We sold that book, and assumed we were going to write it after she was done with her current novel and after I was done drafting The Briar Club.

But our mutual publisher wanted it sooner. So I ended up putting The Briar Club aside about 40,000 words in, then taking a year to hammer out my part of The Phoenix Crown with Janie. It wasn't until that first draft was done that I was able to come back to The Briar Club and finish it.

It's the only time I really ever split a book's drafting in half. Normally, my process is you hammer out that first draft as fast as you can. I think my longest was The Rose Code, which took about 13 months to draft, and my shortest was The Diamond Eye, which only took three-and-a-half months flat, which is unusually fast because that was my pandemic book and I honestly think my muse took one look at everything that was going on in the world, and basically said, “I would rather go somewhere more relaxing than this. How about the World War II, eastern front? That sounds great.”

I'm a big believer in you just get the words down. You do not listen to that voice in your head that says, “This is terrible. How can I possibly think I can do this?” Everybody's first drafts are bad. I've heard Jodi Picoult and Nora Roberts and any number of others say, “You can fix a bad page, but you can't fix a blank page.”

You just need to get that first draft down and hammer it out, and then fix it later. And that's always been my process. But it will take somewhere between 4 months and 13 generally.

GR: How do you do your research? Do you write first, then research back into a story or vice versa, or something completely different?

KQ: I will look at anything if it'll get me something good for a book. I do think we are in a great time for research because so much has been digitized.

When I was writing The Diamond Eye, every column that Eleanor Roosevelt wrote for what she called the “My Day” column has been digitized and put online for free. When I was writing The Briar Club, there were so many things that I got out of newspapers.com, just being able to search for what is going on in Washington, D.C., at this time.

And God bless those people on Pinterest who post vintage ads and vintage menus because that's where I get things like, “What did a hat cost in 1952” or “What does a diner menu for a Washington, D.C., diner in the ’50s look like?”

I look at everything from Pinterest, to digitized newspapers to vintage maps, vintage photos, anything and everything goes.

I research when I'm first thinking what the book's going to be about—the stage when you just know that it's going to involve this period of history for these women. When you’re in the plotting stage, that's when you're deep, diving into every aspect of what you know the book is going to be about.

GR: Do you have a list of obscure historic events that you pull into whatever book you're working on?

KQ: I do have a file on my computer that I just call “plot possibilities,” and that is where I often put interesting links or articles to weird, wacky stuff that I find in my feed and see if that might make its way into a book.

It also comes from the people I know. Another writer who I met at a Florida Book Festival happened to mention something called Operation Longhorn, which happened in the ’50s, where the army did these massive war games in Texas, where they invaded a small Texas town, pretending to be a Communist army. Then the town was held under occupation by the faux communists for a couple of weeks, and then another set of troops came in and liberated the town. This whole thing was done with the town's cooperation as a war game in preparation for the potential communist invasion from the U.S.S.R.

She told me about this, and my jaw was on the floor, and I was thinking that is so unbelievably strange, that has got to go in. As soon as I heard about that, I thought that is giving me my entire last act twist for The Briar Club. It upended my entire plot that I had, but I knew as soon as I heard it that “This is the key. This is the thing that will give me that last little bit that I need.”

I won't say how, because it's a bit of a spoiler, but it really made everything fall into place in the last chapter.

GR: Then, what books are you reading now?

KQ: I just finished reading a great historical, which was The Ballad of Jacquotte Delahaye, by Briony Cameron, about a Black female pirate who is trying to carve out her captaincy in the Golden Age of Piracy in Hispaniola. She's also trying to win the heart of the woman she loves. I just finished it, and that was a great read.

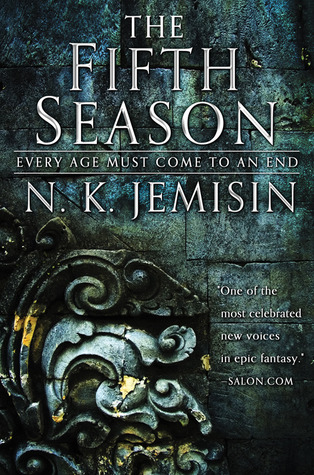

I have also just been diving into a book that's been on my bucket list for a long time, which is N.K. Jemisin’s Broken Earth trilogy. I am just absolutely hooked and don't see myself coming out of that for a long time.

And then The Guncle’s sequel—I can't wait to dive into that, too.

GR: After reading The Briar Club, what's one thing you'd want people to come away with?

KQ: I hope that readers, when they read The Briar Club, will have found a story that they loved, full of women that they admire. I hope that they have some food for thought about what it means to be American and how we can be proud of our homeland, but also temper that pride with the knowledge of where we have gone wrong and how we can do better in the future. If they can walk away with that, I will be very happy.

Kate Quinn's The Briar Club will be available in the U.S. on July 9. Don't forget to add it to your Want to Read shelf. Be sure to also read more of our exclusive author interviews and get more great book recommendations.