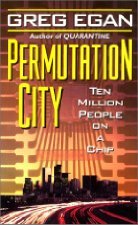

Stuart's Reviews > Permutation City

Permutation City

by

by

Stuart's review

bookshelves: hard-sf, cyberpunk, technology-science

Jul 05, 2013

bookshelves: hard-sf, cyberpunk, technology-science

Read 2 times. Last read May 20, 2016 to May 28, 2016.

Permutation City: Bursting with ideas about artificial life, virtual realities, digital consciousness, etc

Originally posted at Fantasy Literature

Permutation City (1994) won the John W. Campbell Award and is probably Greg Egan’s best-known book. It is a very dense, in-depth examination of digital vs.physical consciousness, computer simulations of complex biological systems, virtual reality constructs, and multi-dimensional quantum universes. Yeah, pretty intimidating stuff. In fact, it was so over my head the first time I gave up in defeat. Then it started to bother me - such mind-boggling ideas were worth another attempt. So I listened to the book again and…I think I got some of it. The final third of the book is still beyond my comprehension, but the first two thirds present two carefully-described ideas that are worth examining - Dust Theory and the TVC universe. Piqued your interest? If so, read on.

Permutation City details attempts in the mid-21st century to create an artificial universe based in the Autoverse, a computer-generated environment where digital copies of wealthy people can enjoy a limited form of immortality in virtual reality. Most books would be content to go with that, but Egan is just getting started. Mysterious entrepreneur Paul Durham is pitching to aging millionaires a far-superior and more secure version of the Autoverse, and also hires solo programmer Maria to create a digital simulation of the early conditions on Earth that gave rise to life. He is stingy with the details, but Maria needs the money to help her ailing mother, so she signs on.

The only way for Paul to test the quality of the digital copies of his clients’ consciousnesses is to try it on himself. But each time he makes a copy, they choose to terminate themselves almost immediately. After numerous tries, he decides to remove their bailout option, forcing a copy of himself to remain “alive” and cooperate with him to further the project. This bears a superficial resemblance to Robert J. Sawyer’s The Terminal Experiment, but that book took the cheap Michael Crichton techno-thriller route, whereas Permutation City is exponentially more intelligent and ambitious.

During his experiments with his digital copy, he discovers that even if he rearranges the chronological order of distinct slices of the copies’ consciousness, his copy still experiences events in an internally-consistent way that defies expectation. There’s no was for me to explain it, other than to quote the text:

Now he was…dust. To an outside observer, these ten seconds had been ground up into ten thousand uncorrelated moments and scattered throughout real time - and in model time, the outside world had suffered an equivalent fate. Yet the pattern of his awareness remained perfectly intact: somehow he found himself, “assembled himself” from these scrambled fragments. He’d been taken apart like a jigsaw puzzle - but his dissection and shuffling were transparent to him. Somehow - on their own terms - the pieces remained connected.

Imagine a universe entirely without structure, without shape, without connections. A cloud of microscopic events, like fragments of space-time … except that there is no space or time. What characterizes one point in space, for one instant? Just the values of the fundamental particle fields, just a handful of numbers. Now, take away all notions of position, arrangement, order, and what’s left? A cloud of random numbers.

But if the pattern that is me could pick itself out from all the other events taking place on this planet, why shouldn’t the pattern we think of as ‘the universe’ assemble itself, find itself, in exactly the same way? If I can piece together my own coherent space and time from data scattered so widely that it might as well be part of some giant cloud of random numbers, then what makes you think that you’re not doing the very same thing?

Is your mind completely blown at this point? I had to read this through these passages several times, attempting to process them. Only by transcribing this was I able to grasp the idea. It may be completely outlandish, but I give Egan kudos for sheer daring. It is a variant of quantum mechanics, but goes a full step beyond that by postulating that the universe can and does take shape from pure randomness each and every moment of our subjective existence. What was he taking when he came up with that? I’m pretty sure I haven’t seen that in hard SF of the time, as this was written back in 1994.

He labels this bizarre concept Dust Theory, and this forms the foundations for an even more dazzling idea, that of the Turing-von Neumann-Chiang (TVC) universe. Again, this is subject matter enough for another book itself. The only way to explain this is to quote Egan again at length:

There’s a cellular automaton called TVC. After Turing, von Neumann and Chiang. Chiang’s version was N-dimensional. That leaves plenty of room for data within easy reach. In two dimensions, the original von Neumann machine had to reach further and further - and wait longer and longer - for each successive bit of data. In a six-dimensional TVC automaton, you can have a three-dimensional grid of computers, which keeps on growing indefinitely - each with its own three-dimensional memory, which can also grow without bound.

And when the simulated TVC universe being run on the physical computer is suddenly shut down, the best explanation for what I’ve witnessed will be a continuation of that universe - an extension made out of dust. Maria could almost see it: a vast lattice of computers, a seed of order in a sea of random noise, extending itself from moment to moment by sheer force of internal logic, “accreting” the necessary building blocks from the chaos of non-space-time by the very act of defining space and time.

By this point Egan had either excited computer science and quantum physics geeks into paroxysms of pure ecstasy, or driven liberal arts majors running screaming in the other direction. Initially I just couldn’t get it, but after transcribing it, I find it makes some sense if you accept the initial assumptions (a big if, of course). But believe it or not, this is still the halfway point of Permutation City, and things get EVEN MORE MIND-BOGGLING as it proceeds. The question arises of whether the TVC universe is infinite or will collapse from entropy as most theorists expect of our own universe. Paul Durham’s answer is:

The TVC universe will never collapse. Never. A hundred billion years, a hundred trillion; it makes no difference, it will always be expanding. Entropy is not a problem. Actually, ‘expanding’ is the wrong word; the TVC universe grows like a crystal, it doesn’t stretch like a balloon. Think about it. Stretching ordinary space increases entropy; everything becomes more spread out, more disordered. Building more of a TVC cellular automaton just gives you more room for data, more computing power, more order. Ordinary matter would eventually decay, but these computers aren’t made out of matter. There’s nothing in the cellular automaton’s rules to prevent them from lasting forever.

Durham’s universe - being made of the same “dust” as the real one, merely rearranged itself. The rearrangement was in time as well as space; Durham’s universe could take a point of space-time from just before the Big Crunch, and follow it with another from ten million years BC. And even if there was only a limited amount of “dust” to work with, there was no reason why it couldn’t be reused in different combinations, again and again. The fate of the TVC automaton would only have to make internal sense - and the thing would have no reason, ever, to come to an end.

In Part Two, the story jumps forward in time, to after the TVC universe, now commonly known as Elysium, has been created and six thousand years have passed internally. Moreover, the artificial life that Maria set the initial conditions of, called Autobacterium Lamberti, has gone through billions of years of virtual evolution using the unlimited computing power of the TVC universe, resulting in an entirely new intelligent species. They are insect-like, group-minded, and increasingly inquisitive about their world. However, they are unaware of the creators, humanity, or that their world was created by artificially.

As they start to investigate the founding principles of their world, Paul Durham and Maria become concerned that their experiments will threaten the fundamental principals of the TVC universe, due to a very byzantine thought process that suggests, to the best of my understanding, that it is the understanding of a given universe and its physical laws and properties that determine those laws and properties. So as the Lambertians begin to examine their world more closely, they are undermining the laws set in the Garden-of-Eden configuration. Here are some excerpts:

I think the TVC rules are being undermined - or subsumed into something larger. Do you know why I chose the Autoverse in the first place - instead of real-world physics? Less computation. Easier to seed with life. No nuclear processes. No explanation for the origin of the elements. I thought: in the unlikely event that the planet yielded intelligent life, they’d still only be able to make sense of themselves on our terms. It never occurred to me that they might miss the laws that we know are laws, and circumvent the whole problem. They haven’t settled on any kind of theory, yet. They might still come up with a cellular automaton model - complete with the need for a creator.

We can’t shut them down. I think that proves that they’re already affecting Elysium. If they successfully explain their origins in a way which contradicts the Autoverse rules, then that may distort the TVC rules. Perhaps only in the region where the Autoverse is run - or perhaps everywhere. And if the TVC rules are pulled out from under us…

What a fascinating question - what happens when the artificial life you’ve created starts to investigate its own origins? Will it guess correctly? Or make up its own explanations, religious or otherwise. Flipping the perspective from the created to the creator is just one of the many mind-expanding ideas that Egan seems to have in endless supply.

The end of the book involves Paul and Maria’s efforts to make contact with the Lambertians and convince them that they are indeed creations of humans, and that they should believe in our universe’s laws in order to maintain them. It was pretty difficult to follow this part, even after two listens, but if you could understand Dust Theory and the TVC universe, then perhaps this will make sense to you as well. My mind was somewhat overwhelmed by this point, but I can’t say for sure if it’s the fault the writer so much as my own ability to understand. While many books may have more entertaining characters or plots, Permutation City is one of the most ambitious explorations of digital consciousness, artificial life, and the fundamental assumptions behind our quantum universe that I have ever encountered. It’s not an easy read, but it will expand your mind.

Notes on the Audible version:

Just as he was for Quarantine, narrator Adam Epstein really is hopeless, especially his atrocious Australian, German, Italian, Russian, and Chinese accents. It would be one thing to do all those accents in the most stereotyped and insulting way possible, but he somehow manages to switch accents for the SAME CHARACTER mid-dialogue. It’s like a painful sketch on Saturday Night Live. Sometimes I was reduced to tears of laughter hearing how awful they were. It makes me wonder if he modeled his accents on the bad guys in action movies. He also regularly mispronounced words. Of the many cringe-worthy mistakes he made in this book, I laughed the most at his misreading of “causal structure” as “casual structure”. However, it’s not surprising that his audiobooks are just $1.99 each, but it’s really a disfavor to Greg Egan’s work. In the end, I would probably appreciate Permutation City much more if I had read the Kindle version (which is only $2.99). I still might not fully understand it, but at least I can do better accents.

Originally posted at Fantasy Literature

Permutation City (1994) won the John W. Campbell Award and is probably Greg Egan’s best-known book. It is a very dense, in-depth examination of digital vs.physical consciousness, computer simulations of complex biological systems, virtual reality constructs, and multi-dimensional quantum universes. Yeah, pretty intimidating stuff. In fact, it was so over my head the first time I gave up in defeat. Then it started to bother me - such mind-boggling ideas were worth another attempt. So I listened to the book again and…I think I got some of it. The final third of the book is still beyond my comprehension, but the first two thirds present two carefully-described ideas that are worth examining - Dust Theory and the TVC universe. Piqued your interest? If so, read on.

Permutation City details attempts in the mid-21st century to create an artificial universe based in the Autoverse, a computer-generated environment where digital copies of wealthy people can enjoy a limited form of immortality in virtual reality. Most books would be content to go with that, but Egan is just getting started. Mysterious entrepreneur Paul Durham is pitching to aging millionaires a far-superior and more secure version of the Autoverse, and also hires solo programmer Maria to create a digital simulation of the early conditions on Earth that gave rise to life. He is stingy with the details, but Maria needs the money to help her ailing mother, so she signs on.

The only way for Paul to test the quality of the digital copies of his clients’ consciousnesses is to try it on himself. But each time he makes a copy, they choose to terminate themselves almost immediately. After numerous tries, he decides to remove their bailout option, forcing a copy of himself to remain “alive” and cooperate with him to further the project. This bears a superficial resemblance to Robert J. Sawyer’s The Terminal Experiment, but that book took the cheap Michael Crichton techno-thriller route, whereas Permutation City is exponentially more intelligent and ambitious.

During his experiments with his digital copy, he discovers that even if he rearranges the chronological order of distinct slices of the copies’ consciousness, his copy still experiences events in an internally-consistent way that defies expectation. There’s no was for me to explain it, other than to quote the text:

Now he was…dust. To an outside observer, these ten seconds had been ground up into ten thousand uncorrelated moments and scattered throughout real time - and in model time, the outside world had suffered an equivalent fate. Yet the pattern of his awareness remained perfectly intact: somehow he found himself, “assembled himself” from these scrambled fragments. He’d been taken apart like a jigsaw puzzle - but his dissection and shuffling were transparent to him. Somehow - on their own terms - the pieces remained connected.

Imagine a universe entirely without structure, without shape, without connections. A cloud of microscopic events, like fragments of space-time … except that there is no space or time. What characterizes one point in space, for one instant? Just the values of the fundamental particle fields, just a handful of numbers. Now, take away all notions of position, arrangement, order, and what’s left? A cloud of random numbers.

But if the pattern that is me could pick itself out from all the other events taking place on this planet, why shouldn’t the pattern we think of as ‘the universe’ assemble itself, find itself, in exactly the same way? If I can piece together my own coherent space and time from data scattered so widely that it might as well be part of some giant cloud of random numbers, then what makes you think that you’re not doing the very same thing?

Is your mind completely blown at this point? I had to read this through these passages several times, attempting to process them. Only by transcribing this was I able to grasp the idea. It may be completely outlandish, but I give Egan kudos for sheer daring. It is a variant of quantum mechanics, but goes a full step beyond that by postulating that the universe can and does take shape from pure randomness each and every moment of our subjective existence. What was he taking when he came up with that? I’m pretty sure I haven’t seen that in hard SF of the time, as this was written back in 1994.

He labels this bizarre concept Dust Theory, and this forms the foundations for an even more dazzling idea, that of the Turing-von Neumann-Chiang (TVC) universe. Again, this is subject matter enough for another book itself. The only way to explain this is to quote Egan again at length:

There’s a cellular automaton called TVC. After Turing, von Neumann and Chiang. Chiang’s version was N-dimensional. That leaves plenty of room for data within easy reach. In two dimensions, the original von Neumann machine had to reach further and further - and wait longer and longer - for each successive bit of data. In a six-dimensional TVC automaton, you can have a three-dimensional grid of computers, which keeps on growing indefinitely - each with its own three-dimensional memory, which can also grow without bound.

And when the simulated TVC universe being run on the physical computer is suddenly shut down, the best explanation for what I’ve witnessed will be a continuation of that universe - an extension made out of dust. Maria could almost see it: a vast lattice of computers, a seed of order in a sea of random noise, extending itself from moment to moment by sheer force of internal logic, “accreting” the necessary building blocks from the chaos of non-space-time by the very act of defining space and time.

By this point Egan had either excited computer science and quantum physics geeks into paroxysms of pure ecstasy, or driven liberal arts majors running screaming in the other direction. Initially I just couldn’t get it, but after transcribing it, I find it makes some sense if you accept the initial assumptions (a big if, of course). But believe it or not, this is still the halfway point of Permutation City, and things get EVEN MORE MIND-BOGGLING as it proceeds. The question arises of whether the TVC universe is infinite or will collapse from entropy as most theorists expect of our own universe. Paul Durham’s answer is:

The TVC universe will never collapse. Never. A hundred billion years, a hundred trillion; it makes no difference, it will always be expanding. Entropy is not a problem. Actually, ‘expanding’ is the wrong word; the TVC universe grows like a crystal, it doesn’t stretch like a balloon. Think about it. Stretching ordinary space increases entropy; everything becomes more spread out, more disordered. Building more of a TVC cellular automaton just gives you more room for data, more computing power, more order. Ordinary matter would eventually decay, but these computers aren’t made out of matter. There’s nothing in the cellular automaton’s rules to prevent them from lasting forever.

Durham’s universe - being made of the same “dust” as the real one, merely rearranged itself. The rearrangement was in time as well as space; Durham’s universe could take a point of space-time from just before the Big Crunch, and follow it with another from ten million years BC. And even if there was only a limited amount of “dust” to work with, there was no reason why it couldn’t be reused in different combinations, again and again. The fate of the TVC automaton would only have to make internal sense - and the thing would have no reason, ever, to come to an end.

In Part Two, the story jumps forward in time, to after the TVC universe, now commonly known as Elysium, has been created and six thousand years have passed internally. Moreover, the artificial life that Maria set the initial conditions of, called Autobacterium Lamberti, has gone through billions of years of virtual evolution using the unlimited computing power of the TVC universe, resulting in an entirely new intelligent species. They are insect-like, group-minded, and increasingly inquisitive about their world. However, they are unaware of the creators, humanity, or that their world was created by artificially.

As they start to investigate the founding principles of their world, Paul Durham and Maria become concerned that their experiments will threaten the fundamental principals of the TVC universe, due to a very byzantine thought process that suggests, to the best of my understanding, that it is the understanding of a given universe and its physical laws and properties that determine those laws and properties. So as the Lambertians begin to examine their world more closely, they are undermining the laws set in the Garden-of-Eden configuration. Here are some excerpts:

I think the TVC rules are being undermined - or subsumed into something larger. Do you know why I chose the Autoverse in the first place - instead of real-world physics? Less computation. Easier to seed with life. No nuclear processes. No explanation for the origin of the elements. I thought: in the unlikely event that the planet yielded intelligent life, they’d still only be able to make sense of themselves on our terms. It never occurred to me that they might miss the laws that we know are laws, and circumvent the whole problem. They haven’t settled on any kind of theory, yet. They might still come up with a cellular automaton model - complete with the need for a creator.

We can’t shut them down. I think that proves that they’re already affecting Elysium. If they successfully explain their origins in a way which contradicts the Autoverse rules, then that may distort the TVC rules. Perhaps only in the region where the Autoverse is run - or perhaps everywhere. And if the TVC rules are pulled out from under us…

What a fascinating question - what happens when the artificial life you’ve created starts to investigate its own origins? Will it guess correctly? Or make up its own explanations, religious or otherwise. Flipping the perspective from the created to the creator is just one of the many mind-expanding ideas that Egan seems to have in endless supply.

The end of the book involves Paul and Maria’s efforts to make contact with the Lambertians and convince them that they are indeed creations of humans, and that they should believe in our universe’s laws in order to maintain them. It was pretty difficult to follow this part, even after two listens, but if you could understand Dust Theory and the TVC universe, then perhaps this will make sense to you as well. My mind was somewhat overwhelmed by this point, but I can’t say for sure if it’s the fault the writer so much as my own ability to understand. While many books may have more entertaining characters or plots, Permutation City is one of the most ambitious explorations of digital consciousness, artificial life, and the fundamental assumptions behind our quantum universe that I have ever encountered. It’s not an easy read, but it will expand your mind.

Notes on the Audible version:

Just as he was for Quarantine, narrator Adam Epstein really is hopeless, especially his atrocious Australian, German, Italian, Russian, and Chinese accents. It would be one thing to do all those accents in the most stereotyped and insulting way possible, but he somehow manages to switch accents for the SAME CHARACTER mid-dialogue. It’s like a painful sketch on Saturday Night Live. Sometimes I was reduced to tears of laughter hearing how awful they were. It makes me wonder if he modeled his accents on the bad guys in action movies. He also regularly mispronounced words. Of the many cringe-worthy mistakes he made in this book, I laughed the most at his misreading of “causal structure” as “casual structure”. However, it’s not surprising that his audiobooks are just $1.99 each, but it’s really a disfavor to Greg Egan’s work. In the end, I would probably appreciate Permutation City much more if I had read the Kindle version (which is only $2.99). I still might not fully understand it, but at least I can do better accents.

Sign into Goodreads to see if any of your friends have read

Permutation City.

Sign In »

Quotes Stuart Liked

“There’s a cellular automaton called TVC. After Turing, von Neumann and Chiang. Chiang’s version was N-dimensional. That leaves plenty of room for data within easy reach. In two dimensions, the original von Neumann machine had to reach further and further - and wait longer and longer - for each successive bit of data. In a six-dimensional TVC automaton, you can have a three-dimensional grid of computers, which keeps on growing indefinitely - each with its own three-dimensional memory, which can also grow without bound.

And when the simulated TVC universe being run on the physical computer is suddenly shut down, the best explanation for what I’ve witnessed will be a continuation of that universe - an extension made out of dust. Maria could almost see it: a vast lattice of computers, a seed of order in a sea of random noise, extending itself from moment to moment by sheer force of internal logic, “accreting” the necessary building blocks from the chaos of non-space-time by the very act of defining space and time.”

― Permutation City

And when the simulated TVC universe being run on the physical computer is suddenly shut down, the best explanation for what I’ve witnessed will be a continuation of that universe - an extension made out of dust. Maria could almost see it: a vast lattice of computers, a seed of order in a sea of random noise, extending itself from moment to moment by sheer force of internal logic, “accreting” the necessary building blocks from the chaos of non-space-time by the very act of defining space and time.”

― Permutation City

“The TVC universe will never collapse. Never. A hundred billion years, a hundred trillion; it makes no difference, it will always be expanding. Entropy is not a problem. Actually, ‘expanding’ is the wrong word; the TVC universe grows like a crystal, it doesn’t stretch like a balloon. Think about it. Stretching ordinary space increases entropy; everything becomes more spread out, more disordered. Building more of a TVC cellular automaton just gives you more room for data, more computing power, more order. Ordinary matter would eventually decay, but these computers aren’t made out of matter. There’s nothing in the cellular automaton’s rules to prevent them from lasting forever.

Durham’s universe - being made of the same “dust” as the real one, merely rearranged itself. The rearrangement was in time as well as space; Durham’s universe could take a point of space-time from just before the Big Crunch, and follow it with another from ten million years BC. And even if there was only a limited amount of “dust” to work with, there was no reason why it couldn’t be reused in different combinations, again and again. The fate of the TVC automaton would only have to make internal sense - and the thing would have no reason, ever, to come to an end.”

― Permutation City

Durham’s universe - being made of the same “dust” as the real one, merely rearranged itself. The rearrangement was in time as well as space; Durham’s universe could take a point of space-time from just before the Big Crunch, and follow it with another from ten million years BC. And even if there was only a limited amount of “dust” to work with, there was no reason why it couldn’t be reused in different combinations, again and again. The fate of the TVC automaton would only have to make internal sense - and the thing would have no reason, ever, to come to an end.”

― Permutation City

“Now he was…dust. To an outside observer, these ten seconds had been ground up into ten thousand uncorrelated moments and scattered throughout real time - and in model time, the outside world had suffered an equivalent fate. Yet the pattern of his awareness remained perfectly intact: somehow he found himself, “assembled himself” from these scrambled fragments. He’d been taken apart like a jigsaw puzzle - but his dissection and shuffling were transparent to him. Somehow - on their own terms - the pieces remained connected.

Imagine a universe entirely without structure, without shape, without connections. A cloud of microscopic events, like fragments of space-time … except that there is no space or time. What characterizes one point in space, for one instant? Just the values of the fundamental particle fields, just a handful of numbers. Now, take away all notions of position, arrangement, order, and what’s left? A cloud of random numbers.

But if the pattern that is me could pick itself out from all the other events taking place on this planet, why shouldn’t the pattern we think of as ‘the universe’ assemble itself, find itself, in exactly the same way? If I can piece together my own coherent space and time from data scattered so widely that it might as well be part of some giant cloud of random numbers, then what makes you think that you’re not doing the very same thing?”

― Permutation City

Imagine a universe entirely without structure, without shape, without connections. A cloud of microscopic events, like fragments of space-time … except that there is no space or time. What characterizes one point in space, for one instant? Just the values of the fundamental particle fields, just a handful of numbers. Now, take away all notions of position, arrangement, order, and what’s left? A cloud of random numbers.

But if the pattern that is me could pick itself out from all the other events taking place on this planet, why shouldn’t the pattern we think of as ‘the universe’ assemble itself, find itself, in exactly the same way? If I can piece together my own coherent space and time from data scattered so widely that it might as well be part of some giant cloud of random numbers, then what makes you think that you’re not doing the very same thing?”

― Permutation City

Reading Progress

Finished Reading

July 5, 2013

– Shelved as:

to-read

July 5, 2013

– Shelved

July 5, 2013

– Shelved as:

hard-sf

May 10, 2016

– Shelved as:

cyberpunk

May 10, 2016

– Shelved as:

technology-science

May 20, 2016

–

Started Reading

May 28, 2016

–

Finished Reading

Comments Showing 1-8 of 8 (8 new)

date newest »

newest »

newest »

newest »

Yes, in hindsight I don't think Egan's work is suited to audio at all, though Quarantine wasn't that hard to understand. This book is definitely for computing/physics/math super-geeks, and while I sometimes imagine how cool it would be to understand what they are talking about, that link you provide says it all - complex and incoherent debate on his Dust Theory.

Yes, in hindsight I don't think Egan's work is suited to audio at all, though Quarantine wasn't that hard to understand. This book is definitely for computing/physics/math super-geeks, and while I sometimes imagine how cool it would be to understand what they are talking about, that link you provide says it all - complex and incoherent debate on his Dust Theory.I actually started Diaspora and got through the first chapter about the birth of the AI but decided to give up at that point. If I want to give his stuff a fair chance, it needs to be in print.

Some of his work should work fine as audio I think. That's just a guess though (I'm not really qualified to make a judgement).

Some of his work should work fine as audio I think. That's just a guess though (I'm not really qualified to make a judgement).His award-winning novella Oceanic for instance is a funny yet rather touching low-confusion work which doesn't require taking notes (which kind of gives the lie to my post above). Many of his short stories have plots and no maths.

In many cases, Egan apparently chose to write longer stories when he wanted to go crazy deep into something... which typically involves maths. But even if you only consider book-length works, Zendegi is pretty mainstream (while sticking with some of Permutation City's themes).

The first chapter of Diaspora is a piece of cake (relative to some other chapters) if I recall correctly: it's got the usual amount of dimensions and so forth.

Two thirds of this went over my head too. My main misgiving though was the lack of dramatization. Too many talking heads and not enough story.

Two thirds of this went over my head too. My main misgiving though was the lack of dramatization. Too many talking heads and not enough story.

It's good that you made some sense of the book but I think you're too charitable.

It's good that you made some sense of the book but I think you're too charitable.You might have misunderstood how the dust argument relates to quantum mechanics. I've read the short version (Dust, 1992) which might be clearer but it's got more to do with relativity (which is to say not much - see link above). The way I see it, it's really about philosophy (see for instance: epiphenomenalism) and ends up illustrating a problem with Egan's philosophical outlook. Definitely up the alley of some "liberal arts majors".

How the dust arguement relates to QM and philosophy might also be made clearer (if you don't mind the crazy talk) by Hans Moravec in a piece which effectively embraces the dust argument. According to Karen Burnham, Moravec has inspired many of Egan's ideas by the way (though possibly not that one).

Both the theoretical dust and the QM stuff are only necessary to appease an attachement to the existence of a physical world somewhere. A few Egan stories dealing with the some of the same issues involve only maths and work just as well.

"he discovers that even if he rearranges the chronological order of distinct slices of the copies’ consciousness, his copy still experiences events in an internally-consistent way that defies expectation"

Why would the result of the expermient defy expectation? In the book, isn't it the expected result (as it is in the short story)? The problem is with the interpretation.

What defied my expectation is that reasonable people have convinced themselves that to say that one reorders "slices" of consciousness is anything other than nonsense. Egan used a sleight of hand by claiming the simulation was computed out of order... which is impossible. Egan acknowledged that himself but claims it's merely a "dramatization" that makes things easier for the reader. That's weak by his standards as he didn't paper over a detail but what dust theory hinges on, namely that consciousness is akin to a video which is a collection of images to which the observer provides an illusion of continuity (when they're played in the right order) rather than a necessary feature of certain complex causal relationships (and therefore not of any static data which might be obtained from such systems). He acknowledged himself that the real point of the theory "is that there is nothing more to causality than the correlations between states". If he'd made that clearer in the story, maybe it would have been less perplexing (if less intriguing).

I would have thought Diaspora was his best-known book but he's known as a short fiction writer anyway.

It's almost as if the popularity of his stuff was driven by perverts: the more confusing it is, the better.