How ‘Tiny Terror’ Truman Capote reeled in wealthy women with dull husbands – then betrayed them

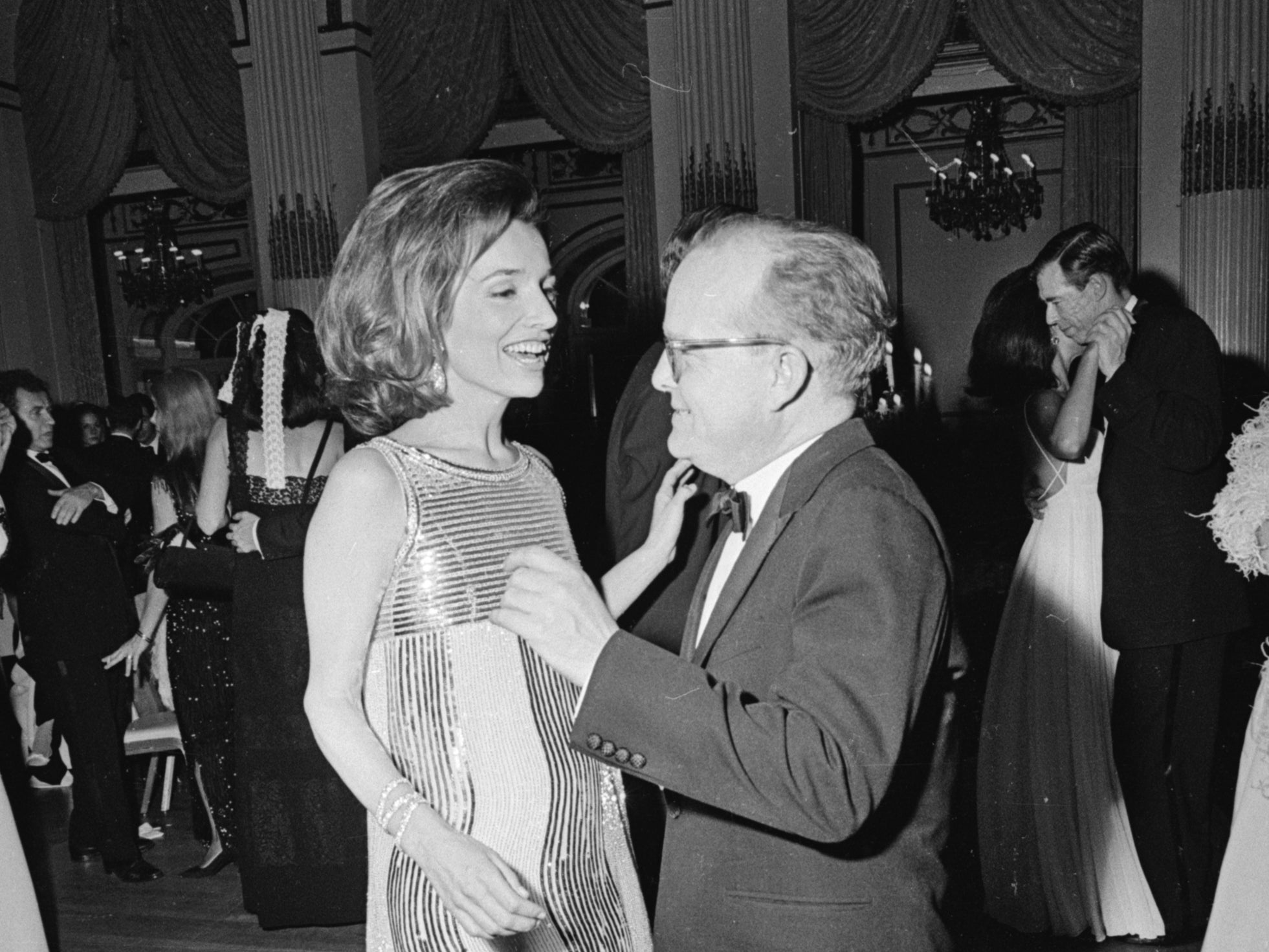

Truman Capote was captivated by his set of wealthy, glamorous ‘swans’. Laurence Leamer’s mash-up of literary biography and celebrity gossip is as enthralled by them as the ‘In Cold Blood’ author himself, writes Robert McCrum

In the United States, some of its greatest writers, from Mark Twain onwards, have led self-invented, double lives with all the perils of half-truths. Among American bestsellers, few were as seductive, or as monstrous, as Truman Streckfus Persons, aka the “Tiny Terror”, Truman Capote. Self-fabricating, and finally self-destructive, the celebrated author of In Cold Blood and Breakfast At Tiffany’s died of drink, drugs and degeneration in 1984, shattered by the failure of Answered Prayers, what he boasted would be the novel of the age, his “magnum opus”. Since then, Capote’s life and work have inspired two feature films (Infamous, starring Toby Jones in 2006; and Capote, with Philip Seymour Hoffman in 2005), plus a major 1988 biography by Gerald Clarke.

Within the hothouse of American fame, this captivating afterlife has inspired some bewildering sub-plots. In Capote’s Women, Laurence Leamer, described as “a leading biographer of the rich and scandalous”, becomes the perpetrator of a breathless rapprochement between literary exegesis and celebrity gossip.

Where Leamer struggles with Truman, the precocious upstart from the South, he revels in the socio-sexual mountaineering of his “swans”, the posh wives whom a lonely homosexual courted with the desperate ardour of the outsider. Here, in that old flirtation between gay men and smart women, the reader watches the hot air of magazine journalism inflate the sad story of a writer who flew too close to the sun.

Capote’s swans – Barbara “Babe” Paley; Gloria Guinness; “Slim” Keith; Pamela Harriman; CZ Guest; Lee Radziwill, Jackie Kennedy’s sister; Marella Agnelli – are mostly forgotten now, but had this in common: they were “perhaps not born rich,” said Capote, “but born to be rich.”

WH Auden, dismissing vulgar biographical speculation, wrote that “A shilling life will give you all the facts.” With Capote, those essential facts were willed into life by his super-charged self-dramatisation. For instance: his mother, Lillie Mae, was an abusive nymphomaniac who became “the single worst person in my life”. He’d grown up determined to overcome his tiny, freakish appearance – an impervious, super-confident expression lit up with a bitchy, combative smile that seemed to invite mischief. “Seduction – that’s what I do,” he’d declare in his high-pitched shriek.

After the 1948 publication of Other Voices, Other Rooms, his risque, semi-autobiographical first novel, replete with its highly suggestive author photograph, Capote became one of New York’s most notorious literary icons. The elfin figure, flouncing through the city streets in a long, trailing scarf en route to the Everard Baths, was a familiar sight. Capote was always outrageous. “The kind of camp I’d never seen before,” said one observer. “Mincing and fluttering.”

It was this shocking flamboyance, his glittering effrontery, that reeled in wealthy women with boring husbands. “No one loves me,” Capote would sigh. “I’m a freak.” So of course they only adored him even more, opening their icy, rich hearts. Capote, the lost boy, would sail on their yachts, swim in their pools, and gossip at their dinner tables, a weird, transgressive mix of grand vizier and court jester.

He was enthralled – and so is this biographer of “the rich and scandalous”. Leamer devotes far too much attention, in brittle magazine cliches, to the loves and lives of these women. But Capote holds our attention, while the gaudy nights of Palm Springs fade. Capote’s swans loved him back, but they did not trust him. “Slim” Keith nailed it when advising a friend never to confide in the Tiny Terror. “Bad news,” she warned. “He’s going to rat you out.”

During the 1950s, Capote’s quest for love and money soared in vertiginous flight. With 1958’s Breakfast At Tiffany’s and the triumph of Holly Golightly, almost immediately filmed starring Audrey Hepburn in 1961, he had the American book world at his feet. But he was not satisfied. When his mother died, he conceived his magnum opus: a novel about women whose dreams of riches were fulfilled, but who ended up with the taste of ashes. Working title: Answered Prayers. Little did these swans know, when they listened to his entrancing self-advertisements, that he wanted to immortalise and betray them, killing the thing he loved. What could possibly go wrong? Answer: everything.

In November 1959, while Capote struggled to write “the greatest novel of the age”, he became distracted, then obsessed, by a New York Times crime story, a Midwest killing of a Kansas farmer and his family whose qualities of mythic horror also opened up the dark underbelly of post-war America.

Falling, as it does, in the middle of Leamer’s tale about Capote’s women, In Cold Blood presents a problem. Capote’s masterpiece, about the brutal, senseless killings of the Clutter family in a sleepy Kansas town, exposes all his strengths and weaknesses. Its glamour is sick, sinister and mercilessly dark. Worse, to write it, Capote fastened onto another female confidante, but she was neither rich nor posh. She was “Nelle”, Harper Lee, the best-selling author of To Kill A Mockingbird, a childhood friend.

He’d always maintained that his swans were ‘too dumb’ to see what he had done. But they weren’t

Without Nelle, who smoothed Capote’s passage through Kansas, there might never have been this bestselling true crime story to which Capote devoted six blighted years. Always the self-promoter, he claimed a special genius for his new book. It was unique; and great, of course. A “non-fiction novel”, a pitch that sent the critics into a spin.

Leamer’s fusion of literature and celebrity comes unstuck here. It was In Cold Blood not Answered Prayers that broke Capote. He himself put it best. “No one will ever know what In Cold Blood took out of me… I think it killed me.”

Leamer dallies with this inconvenient distraction for barely a dozen pages before returning to the congenial society of “the richest, most elegant women in the world”, breezily reporting that “Truman was swept up onto the great train of celebrity from which he never disembarked for the rest of his life.”

After In Cold Blood, awkwardly for Leamer, the humiliating denouement of Answered Prayers was a damp squib. In 1975, corrupted by movie money and unable to complete even a novella-length manuscript, Capote published “La Cote Basque 1965”, an 11,000-word extract from his work-in-progress, in Esquire.

He’d always maintained that his swans were “too dumb” to see what he had done. But they weren’t. His phone fell silent, and the invitations dried up. Worse than the betrayal of his friends was Capote’s betrayal of his gifts. Answered Prayers was a dud. Nine years later, he was dead.

One of the swans saved his ashes, in two urns.

‘Capote’s Women’ by Laurence Leamer (Hodder, £25.00, pp. 356)

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments