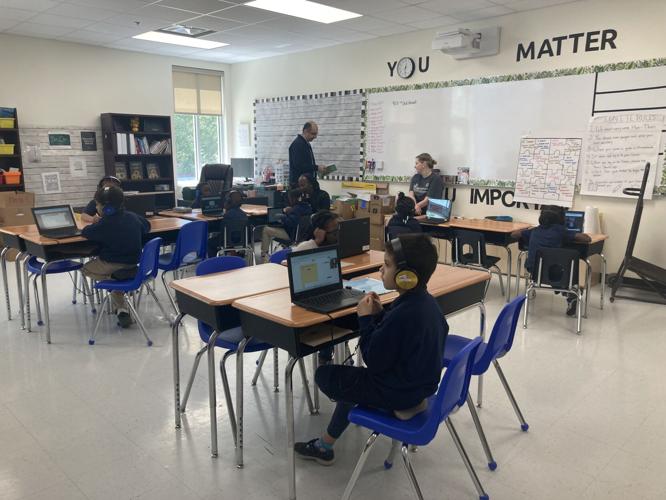

More than two dozen headphone-clad first graders at Kenilworth Science and Technology Charter School sat quietly at their desks on a recent afternoon, listening with rapt attention as their instructors — college students from across the country — virtually guided them through individual reading lessons.

The scene is one of many taking place in schools throughout Baton Rouge and beyond as part of Teach for America’s Ignite program, a tutoring program that the national teacher-recruitment organization founded four years ago to mitigate reading challenges brought on by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Danielle Wilson, a first grade teacher at Kenilworth Science and Technology Academy in Baton Rouge, monitors her students as they sit for virtual sessions with college-age tutors as part of Teach for America’s Ignite literacy program.

Since 2020, districts throughout the U.S. struggling to find ways to improve student test scores after pandemic-related learning declines have dipped into federal COVID aid to ramp up tutoring in schools. Some have turned to programs like Ignite, which recruits college students to provide literacy tutoring to elementary students several days a week via video chat.

Now, it’s one of the models that Louisiana Superintendent of Education Cade Brumley wants districts to consider as he urges the state to expand tutoring to more schools.

“We know how high stakes it is,” said Laura Vinsant, executive director for Teach for America. If a child is not proficient in reading by the time they’re in third grade, “they’re six times more likely to not graduate from high school, so we’re really channeling every resource we have toward literacy.”

Louisiana adds Ignite to its tutoring menu

As schools made the switch to online classes during the pandemic, students everywhere experienced learning setbacks, with students in low-income districts falling even further behind their affluent peers.

To combat declining test scores, many districts invested portions of their federal pandemic-recovery funds into high-impact tutoring. More than 80% of schools nationwide have added tutoring programs since the pandemic, according to federal data.

In Louisiana, test scores in 2021 showed that less than half of public school students in grades K-3 were reading at grade level.

To remedy the issue, Brumley requested $30 million from the Legislature earlier this year to “vastly expand” in-school tutoring, offering schools a menu of options to choose from: paying school staffers to tutor, using tutoring software — including ones powered by A.I — or bringing in outside vendors like Ignite to tutor in person or over video.

Some administrators say hybrid programs like Ignite give students the benefits of connecting with live tutors but still cost less than hiring in-person instructors. Ignite, which is funded through a combination of public and private money, pays its college tutors a modest stipend each semester.

Nationally, Ignite has paired 2,300 tutors with 3,500 students across 21 states. The program targets students in grades K-3.

Earlier this year, Ignite expanded its footprint in the greater Baton Rouge area, dispatching 160 fellows to work with 300 students across six schools.

First graders at Kenilworth Science and Technology Academy in Baton Rouge work virtually with their college-age tutors as part of Teach for America’s Ignite literacy program.

Kenilworth, which opened its new campus along Siegen Lane in Baton Rouge in August, piloted the program with its first graders last fall before deciding to expand the service to third grade a few months later. Principal Hazel Regis said the school targeted students with reading scores in the middle range for tutoring so that the lowest-performing students could stay in the classroom to work more closely with their teachers.

But Regis said the program isn’t just improving kids’ reading scores. Ignite’s college-age tutors come from a diverse array of cultural, racial and geographic backgrounds, allowing students to connect with mentors who understand them while offering a glimpse into other ways of life.

“It’s a blend of having tutors who truly care about supporting them academically,” she said, “but also building those meaningful relationships.”

Coral Crutchfield, an Ignite tutor from St. Paul, Minnesota currently studying at Ohio State University, has witnessed a change in her students.

She pointed to one first grader who initially refused to participate in a lesson if she didn’t know the answers.

“She would just say ‘no,’” Crutchfield said. But as the weeks went by, “she was really excited. As soon as we jumped on the call, she was like, ‘I want to read a story. Can that be the first thing we do?’”

Students make reading gains — and personal connections

Teach For America says Ignite has quickly demonstrated the power of “high-dosage” tutoring, which involves trained tutors working with small groups of students multiple times a week for an extended period. The benefits include accelerated learning and a greater sense of belonging as tutors center lessons around weekly themes related to identity and improving self-confidence.

Every school that partners with Ignite sets goals for how fluent it expects students to be in reading by the time they finish each grade. During the semester, student progress is monitored through an online platform where tutors create personalized lesson plans based on students' progress in areas like letter sounds, reading fluency, vocabulary and reading comprehension.

In Greater Baton Rouge, 99% of students in grades K-3 who worked with tutors at least three days a week met semester-long reading goals set by their schools, according to Teach for America.

Jackson Elementary in rural East Feliciana Parish, another Ignite program partner, saw a 56% increase in the number of students scoring proficient on their reading assessment in spring 2023, according to a January report by FutureEd, an independent think tank in Washington, D.C. that examined the rise of tutoring in public education.

“You can see how this program can work equally in both urban and rural settings,” said Liz Cohen, policy director at FutureEd and the report’s author. “College students, it turns out, can be very effective tutors.”

She added: “They can build real relationships with students, even over a virtual connection.”

Kenilworth administrators agree their students have seen success by forming bonds with their young adult tutors.

“There were many programs in the past that brought people to read to the kids and things like that,” Kenilworth executive director Hasan Suzuk said. But those programs were often not consistent and failed to engage children on a deeper level, he explained. “With Ignite, they’re able to work one-on-one with a college student. It’s really helpful.”

A first grader at Kenilworth Science and Technology Academy in Baton Rouge works virtually with a college-age tutor as part of Teach for America's Ignite literacy program. Image courtesy of Laura Vinsant, Teach for America.

Kintan Silvany, an Ignite fellow from Philadelphia currently studying at Case Western Reserve University in Ohio, works with three Kenilworth first graders every week. She begins each 40-minute lesson by having her students repeat positive affirmations — “I am smart,” “I am kind,” “I’m a good student” — and sometimes asks one of the students to lead the exercise.

She said that the program has done wonders for their confidence.

“When they first started, they were really, really shy, but the more we’ve gotten into the groove of tutoring, they’ve been great about answering questions,” she said. “They have a lot more initiative now.”

Egypt, one of Silvany’s students, said she enjoys the sessions.

“It’s fun to learn about different things,” she said.

Silvany, who is currently studying abroad in Australia for the spring semester, said she often talks to her students about her experience in another country.

“I feel like it’s slowly instilling the idea that they have the freedom to do something like that in the future,” she said.