In the end, it played out exactly as Thomas Tuchel would have hoped.

Since taking charge of Chelsea in January, this has been Tuchel’s default game plan in big matches. They still look to control matches through possession, but a significant portion of their goals come on the break. They attack with speed behind the opposition defence, and are then content to see out results through deep, old-school, penalty-box defending.

Advertisement

The only surprise was that Chelsea found it so easy, with opponents Manchester City recording their lowest expected goals (xG) figure of their entire season.

While Tuchel picked his expected starting XI, opposite number Pep Guardiola sprung a major surprise with his.

Raheem Sterling was recalled on the left flank, Phil Foden shifted inside and Ilkay Gundogan given the holding role. It was only the second time all season Guardiola has started a match without at least one of his holding midfielders, Fernandinho and Rodri.

Was this a classic case of him “overthinking”? Perhaps, but it’s worth taking a second to examine Guardiola’s possible reasoning.

Fernandinho, now 36, was given the runaround by Mason Mount’s movement in last month’s FA Cup semi-final loss to Chelsea, continually being dragged towards the touchline and outwitted. Rodri, meanwhile, endured a truly dreadful game against the same opponents last season, perhaps his worst in a City shirt, when he was continually caught out of position and unable to stop Chelsea counter-attacks.

Neither man is particularly mobile but Guardiola, of all people, knows that mobility isn’t a prerequisite for the holding midfield role, having played it himself.

Chelsea didn’t necessarily target City in that zone, however. Instead, just as they did successfully in that FA Cup semi-final six weeks ago, they attacked well by switching the play out to their left flank, towards Ben Chilwell.

Both he and Reece James were excellent defensively last night, with Chilwell sticking extremely tight to Riyad Mahrez and James’ pace allowing him to deny Sterling a route to goal. Going forward, though, Chilwell was significantly more influential.

In terms of systems, Guardiola essentially played a back three, a diamond midfield and a front three when in possession, with Oleksandr Zinchenko drifting infield from left-back to form the left-hand point of the diamond.

He has often used this shape over the years in an attempt to stretch the play high up the pitch while dominating the centre of it. It does, however, mean his defenders are forced to cover a large amount of space when the opposition counter-attack.

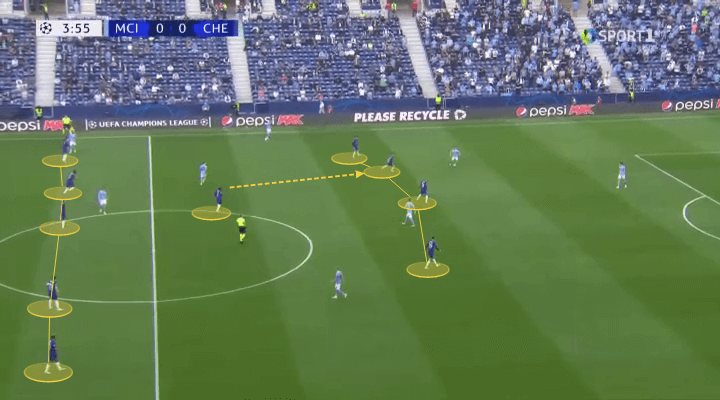

Chelsea stuck to their usual shape, with Tuchel ordering Mount and Kai Havertz to remain in aggressive, central positions to block City’s passing through the middle, rather than dropping back to form a midfield four. It was effectively 5-2-3.

In fact, Chelsea’s shape sometimes ended up looking more like 5-1-4, as one of the holding midfielders would push forward to press the man in possession…

…and although that risked leaving too much space between the lines, Antonio Rudiger and Cesar Azpilicueta were aggressive, always ready to stride forward and shut down the players on the sides of City’s diamond if they received possession.

The real story of the game is Chelsea’s direct passes into attack, particularly towards the left.

It feels like long balls have been an unusually prominent part of top-level European football this season — think, for example, of Real Madrid’s 3-1 quarter-final first-leg win over Liverpool. That’s possibly the consequence of teams still playing high defensive lines but doing so with less pressing, and an increased number of defenders who can play accurate long passes downfield.

Advertisement

Chelsea started the game by rattling John Stones with long balls.

Here, Rudiger looks for Timo Werner with one over the top, with Stones getting himself into a right state when attempting to clear the ball…

…that eventually led to Havertz playing a dangerous cut-back to Werner, who completely miscued his shot when well placed.

A similar situation occurred three minutes later.

Thiago Silva launched the ball out towards James, which dragged Zinchenko forward from left-back and Ruben Dias across from centre-back.

James immediately hit a pass in behind them…

…this again prompted Stones to lose his footing when attempting to deal with the ball, allowing Werner to get in behind. Again, Chelsea played a decent cut-back, this time to N’Golo Kante, who couldn’t bring the ball under control.

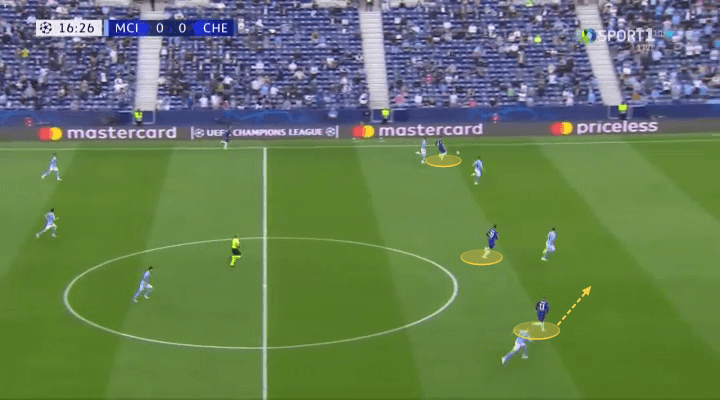

But the key to the game was Chilwell. He would often pop up in overlapping situations when Kyle Walker was preoccupied with the movement of one of Chelsea’s attackers, usually Mount.

Here are a couple of examples of Havertz feeding an unmarked Chilwell on the overlap, with Mahrez nowhere to be seen.

This was most effective when Chelsea found him quickly from defence.

Here, with Silva hitting a long diagonal, the move came to nothing because Chilwell was flagged offside. A wing-back being caught offside felt telling, though.

Chelsea’s goal just before half-time was the culmination of a move they tried three times in the first half — and it’s the same one they utilised so often against City last month.

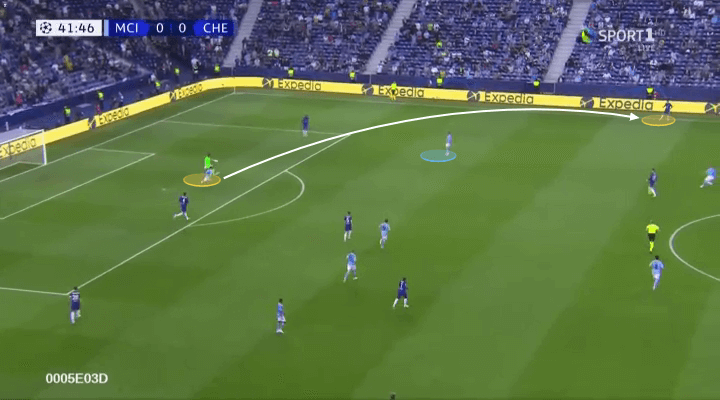

First, there’s a long diagonal from defence.

Here, it’s Silva who plays the pass over the head of Mahrez to Chilwell. This attracts Walker towards Chelsea’s left wing-back, leaving Mount free on the inside…

…Chilwell plays it first time to Mount but sends him down the line, meaning he’s unable to pivot and look for a through ball. In the centre of defence, meanwhile, City look exposed — Zinchenko isn’t in the right position to stop Werner’s run in behind.

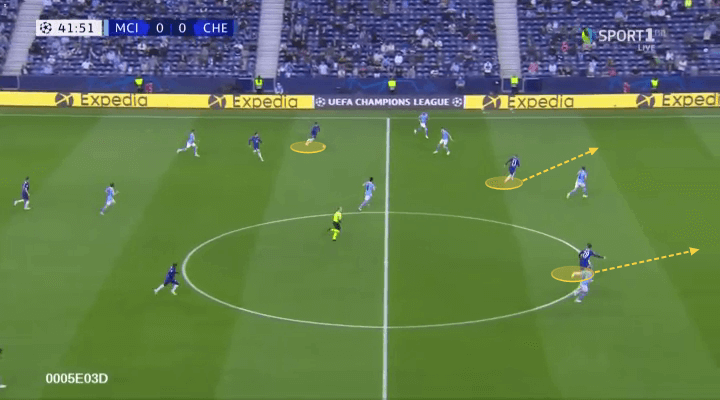

Two minutes before the goal, Chelsea do the same thing.

This time, goalkeeper Edouard Mendy is the player to knock a ball over Mahrez’s head out to Chilwell, which again attracts Walker. For a second time, he immediately plays it past him to Mount.

On this occasion, Stones is tight to him, so Mount can’t turn. City are in a better defensive position in the centre, too, with both men goalside of Chelsea’s attackers.

That move also came to nothing — but City have had two warnings now.

And here’s the goal.

Again, Mendy floats the ball over Mahrez’s head to Chilwell, and you know the drill by now.

Chilwell plays his pass first time, beyond Walker and on to Mount…

…and this time, Mount is in space. This time also, Zinchenko isn’t goalside of his runner, Havertz. Werner makes a run into the left channel to draw Dias out of the equation, which opens up the passing lane for Mount to play a through ball.

In fact, it’s an absolutely huge passing lane and for a player of Mount’s ability, this isn’t a remotely difficult pass to play. The genius is not in the execution itself but in the slight pause just before he hits it, steadying himself and waiting for Havertz to be in the optimum position.

Goalkeeper Ederson can’t stop Havertz from going past him — he actually handles the ball outside his penalty area — and the German seizes on the deflection first and rolls a shot into an empty net.

CHELSEA LEAD! 🔵

A superb pass from Mason Mount and Kai Havertz is cool enough to round the keeper and slot the ball home! 🎯#UCLfinal pic.twitter.com/P2auOn6yk7

— Football on BT Sport (@btsportfootball) May 29, 2021

Would a proper holding midfielder have prevented this goal? Well, he wouldn’t have been in a position to stop Mount directly but he might have been in one that blocked off his through ball to Havertz.

That’s a bit of a stretch, though, and really, City’s problem was the lack of a plan for coping with those long balls out towards Chilwell. Considering this was also their main issue in that FA Cup semi-final between these sides over a month earlier, this is surely a greater oversight than anything to do with the holding midfield position.

Advertisement

The second half was full of suspense but not really packed with tactical intrigue.

Guardiola inevitably summoned both Gabriel Jesus (on 60 minutes) and Sergio Aguero (77), but City lacked any kind of connection between midfield and attack, aside from one piece of play from Foden, who darted through the middle and slipped in Mahrez in a good position. The departure of Kevin De Bruyne on the hour, nursing facial fractures after a collision that saw Rudiger booked, left City lacking ideas in terms of breaking down Chelsea, who switched slightly to a 5-3-2 formation to see out the game.

There haven’t been many underdog victories in Champions League finals, certainly not in recent years. When they have occurred — Liverpool in 2005, Chelsea themselves in 2012 — they’ve tended to be dramatic, almost illogical triumphs rather than comprehensive, deserved wins. Probably not since Borussia Dortmund defeated Juventus in 1997 have underdogs won the final in such a confident manner.

In fact, Chelsea barely had a single scare throughout the entire knockout phase.

This victory would have seemed impossible at the turn of the year, when they were struggling under Frank Lampard, but Tuchel has turned them into the most tactically disciplined side in Europe.