What tactics do England use? What is the USA’s weakness? Which quirk should we look out for from Wales?

The 2022 World Cup is nearly upon us and The Athletic will be running in-depth tactical group guides so you will know what to expect from every nation competing in Qatar.

Liam Tharme will look at each team’s playing style, strengths, weaknesses, key players and highlight things to keep an eye on during the tournament.

Advertisement

Expect to see screengrabs analysing tactical moments in games, embedded videos of key clips to watch, the occasional podcast clip and data visualisation to highlight patterns and trends — think of yourself as a national team head coach and this is a mini opposition dossier for you.

So let’s crack on with Group B, which features four top 25 FIFA-ranked nations in Wales, USA, England and Iran.

You can find Group A here and the rest of the groups (C to H) will be published throughout the week…

Wales

- Manager: Rob Page (since June 2020)

- Captain: Gareth Bale

- UEFA qualifying record: P8, W4, D3, L1, GF19, GA9 (qualified through playoffs)

- 2018 World Cup: Failed to qualify

- Average age of squad in qualifying: 26 years 7 months

- Most caps in squad: Chris Gunter (109)

- Top scorer in squad: Gareth Bale (40)

How they play (tactics and formations)

“It shouldn’t work — but it does” was Tim Spiers’ assessment of Wales’ successful World Cup play-off campaign.

Success for Wales is typically attributed to individual brilliance rather than tactical genius but head coach Rob Page deserves more credit for his strategies — he was rewarded with a new contract ahead of the tournament.

Those strategies centralise around the forwards. Gareth Bale is the centre-piece but Daniel James and Brennan Johnson are similar style players: hybrid winger-forwards who have direct speed and dribbling ability. At times they play as a trio or Bale with one other, but the towering Kieffer Moore offers aerial presence that suits crossing-based attacks. Wales regularly invert players on both wings (a left-footer on the right — Harry Wilson) and there are numerous quality dribblers and off-ball runners.

Regardless of the personnel, Wales largely do not care for possession or organised build-up and do most of their damage on the counter-attack.

Observing the team style graphic below, from Euro 2020, we see that Wales had fewer than average passes per sequence — X axis — which reflects less elaborate, expansive possessions. Plus their above-average direct speed — Y axis — they move the ball forward faster than most, reflecting directness in attack.

Among UEFA countries going to Qatar, in World Cup qualifying, they ranked bottom for possession (48.1%) and open-play sequences of 10+ consecutive passes (78).

At defensive set pieces Page always leaves multiple players upfield to launch quick attacks.

Exhibit A: Aaron Ramsey’s goal against Czech Republic.

Ramsey starts the sequence by flicking the clearance onto Ethan Ampadu…

… who plays into the versatile Neco Williams. Note his split positioning with James either side of Czech Republic’s three defenders. Ramsey continues his box-to-box run…

… Williams whips an early cross and James almost meets it, but it runs through to Ramsey who keeps his composure to control and score.

Y gôl, Y Wal Goch ac Estonia v Cymru 🏴🙌

Cyfweliad gydag @AaronRamsey cyn y gêm ragbrofol Cwpan y Byd 2022 yn erbyn Estonia.

Estonia v Cymru – yn fyw nos Lun am 7.25 ar @S4C pic.twitter.com/nhJFNkZQZ4

— Sgorio ⚽️ (@sgorio) October 10, 2021

A similar counter-attack from the play-off final, versus Ukraine, firstly highlights Welsh defensive deficiencies.

Their wing-back system allows them to be exploited centrally, with only two central midfielders (yellow circles).

The impact is that the centre-backs have to regularly break out from the defensive line to press an opponent receiving between the lines, creating space in-behind for a third-man run.

On this occasion, Joe Rodon has to jump…

… but Williams recovers the ball and beats two opponents to launch the counter…

… he finds James who dribbles inside before threading it through to Moore…

… the cutback finds Ramsey but he shoots wide.

Their key player(s)

Bale, obviously.

The most goals (five) and assists (four) in qualifying, despite only playing 63 per cent of minutes, but delivering without playing regularly is Bale’s game — just check out his role in Los Angeles FC’s MLS Cup win at the weekend. In World Cup qualifying he ranked 10th of all European players, ahead of France’s Kylian Mbappe, for fewest minutes per goal/assist.

His direct free-kick goals carried Wales through the play-offs. Against Ukraine, Andriy Yarmelenko headed an own goal from one and even better was the opener against Austria in the round before.

Seven of Bale’s 20 career direct free-kick goals have been in internationals.

| Year | Opponent | Cap | Competition | Goalkeeper |

|---|---|---|---|---|

2006 | 3 | Euros qualifying | Kamil Contofalsky | |

2012 | 36 | World Cup qualifying | Vladimir Stojkovic | |

2014 | 45 | Euros qualifying | Ferran Pol | |

2015 | 49 | Euros qualifying | Ofir Marciano | |

2016 | 56 | Euros finals | Matus Kozacik | |

2016 | 57 | Euros finals | Joe Hart | |

2022 | 101 | World Cup qualifying | Heinz Lindner |

What’s their weakness?

They struggle to dominate the ball and finish opponents off. Though, if this style is effective anywhere it is undoubtedly tournament football.

They only beat one opponent by more than one goal in qualifying (5-1 vs Belarus) and relied on outstanding individual defending — Wayne Hennessey made nine saves in the win against Ukraine, Ben Davies blocked five shots against Austria.

Advertisement

Wales are worryingly porous defensively for a team that spends so much time without possession. When they do lose it, they rarely win it back immediately, averaging the fewest counter-pressures per match at Euro 2020.

Austria and Ukraine played through Wales to create a big chance.

Austria used a more intricate passing pattern, dissecting a disorganised defence after picking up a second ball.

Whereas Ukraine needed just one pass. The space comes from a centre-back stepping out because the central midfielders are high and an opponent is between the lines.

This pattern led to Poland’s goal in their Nations League win in Cardiff.

There is space to play around the two central midfielders…

… which creates an angle to play directly into the No 9, Robert Lewandowski…

… who flicks it onto Karol Swiderski’s third man run — and he scores.

One thing to watch

Moore. Wales do not have another player of his style.

At 6ft 5in, his aerial presence is remarkable and it makes him a fantastic plan B forward for club (Bournemouth) and country. Since Page took charge in November 2020 only Bale (7) has more goals than Moore (6).

He can act as a focal point for Wales to play long and attack through crosses, but critically provides balance and occupies defenders, which creates space for the dynamic Bale, Johnson and James.

Moore’s nine national team goals have been scored at a rate of one every 197 minutes, which makes him more efficient than Bale (214 minutes per goal).

USMNT

- Manager: Gregg Berhalter (since December 2018)

- Captain: Christian Pulisic/Tyler Adams

- Qualifying record: P14 W7 D4 L3 GF21 GA10

- 2018 World Cup: Failed to qualify

- Average age of squad: 24.2 in qualifying

- Most caps in squad: DeAndre Yedlin (74)

- Top scorer in squad: Christian Pulisic (21)

How they play (tactics and formations)

This tournament will see a new generation of American talent. They are the youngest team to qualify for Qatar, with an average age of 24.2 in qualifying. The 29-year-old DeAndre Yedlin is a veteran in the side and the only one with World Cup experience.

Gregg Berhalter has consistently used a 4-3-3 designed to maximise wide-area quality — he describes his full-backs as the team’s “superpower”.

Advertisement

Christian Pulisic and Brenden Aaronson (blue dots on the grab below) are ‘wingers’ in the front three but have license to roam and regularly drop deeper to receive passes. Both full-backs push forward and central midfielders rotate in to occupy their traditional positions.

An example of this working can be found in the 3-0 win against Morocco. Central midfielder Yunus Musah (yellow dot) pulls wide so left-back Antonee Robinson (red dot) can play further forwards, on the opposition right-back.

When they make these rotations the US rarely try to progress the ball through teams but instead opt to play over. Moving players around like this does leave holes and is ripe for counter-attacks.

On this occasion Walker Zimmerman finds Pulisic running in behind. He squares it to Aaronson for a tap-in.

Visualising this goal demonstrates the attacking approach. Keep the ball, play sideways to move the opposition and bait the press, then exploit.

At times, the central midfielder(s) drops between centre-backs — see below, Tyler Adams against Costa Rica.

Both full-backs are highlighted (yellow dots) and Adams finds DeAndre Yedlin, who crosses.

Defensively they do press but are porous. In CONCACAF qualification, the US allowed opponents the joint-fewest passes before making a defensive action and recorded the most high turnovers per game (9.5).

Though the wingers remain high, set to press opposition centre-backs, this leaves space to play around and into advancing full-backs.

The Uruguay goalkeeper Fernando Muslera regularly exploited this…

The space between the midfield three and defensive line also becomes an issue because the outside central midfielders have to press in wide areas (see Adams in the grab above). This means there is regularly space for opposition goalkeepers to play over the press and bypass six US players.

Their key player(s)

Aaronson and Pulisic aside, it’s Antonee Robinson.

He was second to Adams for minutes played in qualifying and is their best crosser. Berhalter has described him as “relentless attacking” and he often supports counter-attacks with long, forward runs from deep.

The US positional rotations, outlined above, are used to play him further forward. He had the most assists (three) of an American in qualifying and, the defender, nicknamed ‘Jedi’ from childhood, has a tendency to find back-post positions when build-up occurs down the right side.

What’s their weakness?

The No 9 spot. Simply: a variety of good but not great options, who were underperforming and then all came to life at once.

There are different play styles but nobody ticks all the boxes: a clinical goalscorer, able to link play with the wingers and can lead the press.

John Muller’s player roles have likely first-choice Jesus Ferreira as a ‘Roamer’, who can crucially link play to the wingers but is wasteful with his own chances. Jordan Pefok, a ‘Finisher’, is the exact opposite. Josh Sargent is a hybrid winger-forward and profiles as a ‘Target’, but has no outstanding attributes. Timothy Weah is a similar mould.

Ricardo Pepi is the strongest fringe option with 10 caps, but all six of his international goal involvements came in his first two appearances. FC Cincinnati’s Brandon Vazquez and Antalyaspor’s Haji Wright are young and internationally raw, with four caps combined.

One thing to watch

Weston McKennie’s long-throw threat.

His 12 throw-ins into the penalty area were the most of any North American player in qualifying.

Berhalter used this most in the defeat at Canada, with McKennie able to repeatedly launch the ball onto the edge of the six-yard box.

There were no shots from McKennie throws in qualifying but this is undoubtedly a valuable tool in tournament football.

England

- Manager: Gareth Southgate (since September 2016)

- Captain: Harry Kane

- Qualifying record: P10 W8 D2 L0 GF39 GA3

- 2018 World Cup: Semi-finals

- Average age of squad: 26.4

- Most caps in squad: Raheem Sterling (79)

- Top scorer in squad: Harry Kane (51)

Read more: How to win the World Cup: The lessons teams can learn from previous winners

How they play (tactics and formations)

England are relatively unique in that they make their playing philosophy public.

Splitting the game into phases in possession (i.e., attacking) and out-of-possession (i.e., defending), The FA articulate England’s style as to:

- Dominate possession intelligently, selecting the right moments to progress the play and penetrate the opposition

- Regain possession intelligently and as early and as efficiently as possible

- Play with tactical flexibility, based on the profile of the players available and the requirements of the match or competition

Despite the clamour, Gareth Southgate will not field a gung-ho attacking side but instead try to control games. They managed this excellently, up until the final, at Euro 2020.

That tournament, England spent the least time losing (just 1%) and second-most time winning (44%), with only Spain (176) having more open-play sequences of 10+ passes (England — 128). The best moment of control was in the semi-final, where England played keep-ball for over two-and-a-half minutes to see out the win against Denmark.

The demands for them to be tactically flexible were evident last summer. At Euro 2020 Southgate selected a back four in the group stage games but opted for a back three in knockout fixtures against Germany (round of 16) and Italy (final).

The pass networks below illustrate the shape. Brighter circles indicate more touches for the player and bolder lines (minimum five passes between players for a line) reflect higher passing frequencies between team-mates.

By changing shapes England mitigated opposition threats — they kept clean sheets in their first five games for the first time at a European Championship.

They achieved this through a strong defensive shape, compacting the middle third of the pitch and then picking moments to press, rather than repeatedly trying to suffocate opponents as they played out. England only ranked joint-fifth for high turnovers (43) at Euro 2020 and just two of those high turnovers ended in shots. The champions Italy were 56 and 13 in those stats.

Their key player(s)

Harry Kane, for his goals and his creativity.

England’s all-time top scorer in waiting, Kane (51) is just three goals away from surpassing Wayne Rooney’s record (53) and needs just one strike in Qatar to overtake Gary Lineker (also 10) for major tournament goals scored. He was joint-top scorer for non-penalty goals at Euro 2020 (4 with Patrick Schick) and joint-top scorer overall in qualifying (12 with Memphis Depay).

Advertisement

Undoubtedly one of the best penalty takers on the international stage, Kane has scored 16 of his 19 senior England penalties — the trademark, stuttering run-up and finish across the goalkeeper, into the side netting.

John Muller’s player role analysis quantifies Kane’s evolution from a ‘Finisher’ to a ‘Roamer’. He has become synonymous with the through ball at club level and plays these for England, too.

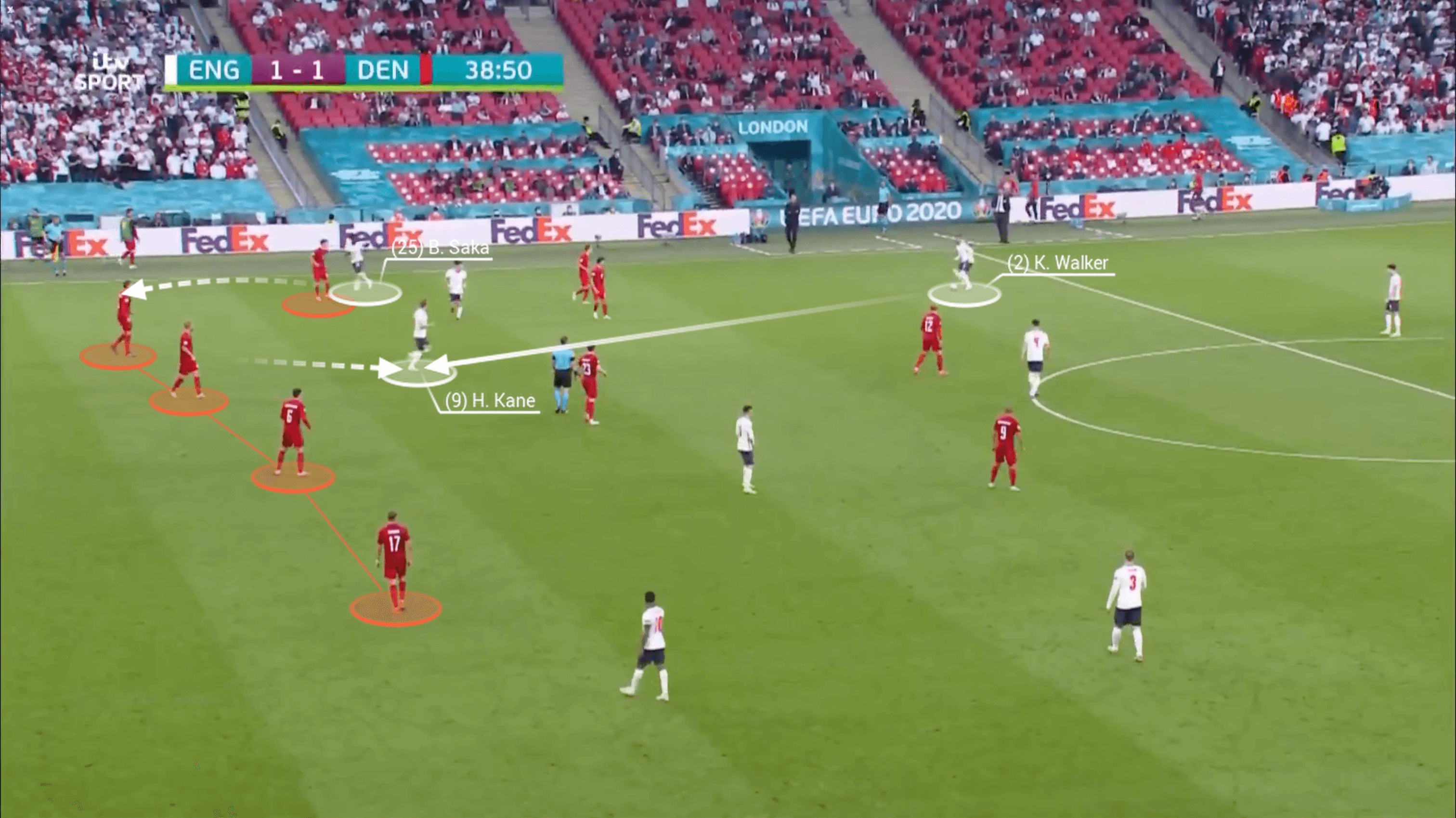

In the Euro 2020 semi-final, he split the Denmark defence in the build-up to England’s equaliser…

And then in the final he was pivotal in the build-up to England’s opener, dropping deep once more before switching play to Kieran Tripper, whose cross led to Luke Shaw’s goal.

What’s their weakness?

The biggest criticism of Southgate is his satisfaction at winning 1-0 rather than attempting to demolish opponents. Often this means possession is used defensively rather than relentless attacking waves.

And England have failed to see out 1-0 leads in significant major tournament games — the Euro 2020 final (Italy), World Cup 2018 semi-final (vs Croatia) and quarter-final (vs Colombia). They did not have a shot on target after scoring in the Euro 2020 final.

Success and failure at international level are often considered generational and almost genetic, but England have never been good at holding onto a lead. Between 2000 and 2020 England had just a 50 per cent win rate after scoring first in major tournament games — Netherlands, France, Belgium, Germany, Spain and Portgual all boasted over 80 per cent figures. In 11 Euros, World Cup and Nations League finals games under Southgate, England have seven wins, two draws and two losses. That rate (63%) is higher than previous iterations but far from truly elite.

Not having a third consistent goalscorer (after Kane and Raheem Sterling) does little to help.

One thing to watch

Set pieces!

These were a cornerstone of England’s 2018 World Cup success — nine of their 12 goals were from set pieces. They took time to score from one at Euro 2020 but ended the tournament top for set piece shot-creating actions (19).

And in World Cup qualifying, including penalties, they were Europe’s best.

| Metric | England WCQ Total | UEFA Rank |

|---|---|---|

Set piece shots | 39 | 4th |

Set piece xG | 9.8 | 2nd |

Set piece goals | 13 | 1st |

All four of Harry Maguire’s World Cup qualifying goals were from set pieces — underlining the lack of goalscoring diversity, he was England’s top scorer behind Kane.

Three from outswinging corners. England used an attacking trio, primarily Kane and Stones with Maguire, to create space by running in different directions.

Iran

- Manager: Carlos Queiroz (since September 2022)

- Captain: Ehsan Hajsafi

- Third round AFC qualifying record: P10, W8, D1, L1, GF15, GA4

- 2018 World Cup: Group stages (3rd place)

- Average age of squad: 28.6 (in qualifying)

- Most caps in squad: Ehsan Hajsafi (114)

- Top scorer in squad: Sardar Azmoun (40)*

* Azmoun is an injury doubt for their World Cup squad

How they play (tactics and formations)

Queiroz is leading Iran to a third consecutive World Cup finals, but this time around the build-up is a little bit different.

The 69-year-old replaced Dragan Skocic in September and has only had two games, both friendlies, to prepare. His last spell in charge of Team Melli was for eight years between 2011 and 2019.

Advertisement

Under Queiroz, Iran’s success has been underpinned by a strong defensive structure — they conceded more than once in just 12 of his 97 games in the previous era and let in just one (an own goal) in those two September friendlies. At World Cup 2018 they conceded just twice in their three games despite being in a group with Spain and Portugal.

In those matches, they shaped up in a 4-1-4-1 without the ball and defended the midfield third of the pitch more than they pressed high.

Iran do not control games with possession and in qualifying, albeit under a different head coach to Queiroz, had the fewest open-play passing sequences of 10-plus passes (84) of the five AFC nations to qualify for Qatar rather than get in automatically as hosts (the other four are Australia, Japan, South Korea and Saudi Arabia).

In both September friendlies, against Uruguay and Senegal, they consistently made good decisions about when to launch a counter-attack and when to retain possession when they won the ball.

Creating chances in attacking transition was a cornerstone of their success in qualifying, with Iran the best Asian side for direct attacks — defined as possessions that start in a team’s defensive half and result in a shot or touch taken inside the opposition penalty area within 15 seconds. They had 21 of these, eight more than second-best Australia, and five of them ended with them scoring, such as Medhi Taremi’s goal against Iraq (2:07 on video below).

🎥 HIGHLIGHTS | 🇮🇶 Iraq 0-3 Iran 🇮🇷

A dominant performance by Iran as they pick up 3 goals and 3 points in Doha! #AsianQualifiers #IRQvIRN pic.twitter.com/FC9zJ8z0Y8

— #AsianCup2023 (@afcasiancup) September 8, 2021

Iran (20) are the highest-ranked Asian side at Qatar and were the continent’s best team in the third and final round of qualifying for points (25), goals scored (15) and goal difference (plus-11).

Despite their counter-attacking quality in the qualifiers, Iran are very capable as an elaborate attacking side. Their goals in the 1-1 draw with Senegal and 1-0 win over Uruguay, two fellow World Cup sides, both started from the goalkeeper and were created by build-up through the thirds.

Advertisement

Let’s start with the Senegal goal.

Both full-backs are advanced and there are three to aim for in the penalty area but right-back Sadegh Moharrami overhits his cross, and it finds opposite-side full-back Ehsan Hajsafi…

… who plays a quick one-two with Alireza Jahanbakhsh to create an angle to cross from high in the half-space…

… and find Sardar Azmoun in the six-yard box to level the scores with the reigning African champions.

Mehdi Taremi got the only goal against Uruguay four days earlier and again it was created through a flowing attacking move and a cross from the left.

He combines with Karim Ansarifard to get past the midfield and then plays wide to Saman Ghoddos…

… which gives the time and creates the space for Ansarifard to burst between full-back and centre-half.

This diagonal run is found by a well-timed Ghoddos pass and the No 10 fires in a low cross for Taremi to convert.

You can watch the final part of the move in all its glory below.

Mehdi Taremi’s goal in the 79th minute provided the W for Iran over Uruguay 🇮🇷😤

(via @FOXDeportes)

— FOX Soccer (@FOXSoccer) September 23, 2022

Their key player(s)

It’s Azmoun and Taremi in attack, but Queiroz’s defensive shape does not have space to start both. that decision might be taken out of his hands anyway if Azmoun is ruled out of the tournament because of the calf injury he suffered last month.

In the September fixtures, Quieroz substituted Azmoun with Taremi on 68 minutes against Uruguay, while the opposite switch was made nine minutes earlier against Senegal.

| Metric | Mehdi Taremi | Sardar Azmoun |

|---|---|---|

60 | 65 | |

4,079 (45.3) | 4,507 (50.1) | |

27 | 41 | |

13 | 7 | |

102 | 93.8 |

Taremi, who plays his club football for Porto, is the most versatile of the two and can operate off the left whereas Bayer Leverkusen’s Azmoun profiles more as a traditional No 9, with heading (as shown with his goal against Senegal) his best attribute. If they were to line up together, expect to see Taremi wide left and Azmoun leading the line.

GO DEEPER

All Iran can do is keep playing, use their voice and hope tomorrow is better

What’s their weakness?

The lack of a plan B.

While the defence-first approach regularly provides Iran with a strong base, when it does not work there are issues in pulling games out of the fire.

Iran have never come from behind to win a game under Queiroz. In his 99 games across two spells, they have been victorious in just 13 of the 42 where they have conceded — the same number as they have lost.

One thing to watch?

Goalkeeper Alireza Beiranvand. He saved a penalty from Cristiano Ronaldo at the previous World Cup four years ago and boasts an impressive record against spot kicks — not conceding from 10 of the 32 faced in his career — but we want to talk about his distribution capabilities, which are quite literally incomparable.

Beiranvand, who plays domestically for Tehran club Persepolis, set the world record for the longest distance throwing a football during a match — over 61 metres (200ft/66 yards) during a 1-0 win over South Korea in 2016.

There were glimpses of this at the World Cup in Russia, too.

The technique looks pretty identical to a javelin throw, launching the ball out from the side of the body, whereas most goalkeepers would normally have an overarm action, like the motion of (fast) bowling a cricket ball.

Beiranvand always uses a run-up to maximise speed and power, and he can regularly throw the ball well past the halfway line.

Monday, November 21: England vs Iran, Khalifa International Stadium. (1pm GMT/8am ET)

Monday, November 21: USMNT vs Wales, Ahmad Bin Ali Stadium (7pm GMT/2pm ET)

Friday, November 25: Wales vs Iran, Ahmad Bin Ali Stadium (10am GMT/5am ET)

Friday, November 25: England vs USMNT, Al Bayt Stadium (7pm GMT/2pm ET)

Tuesday, November 29: Wales vs England, Ahmad Bin Ali Stadium (7pm GMT/2pm ET)

Tuesday, November 29: Iran vs USMNT, Al Thumama Stadium (7pm GMT/2pm ET)