The Saalfelden heat was stifling and, for some players, fatigue appeared to be setting in during the final session of Newcastle United’s punishing July training camp in the Austrian mountains.

But Eddie Howe did not relent. Pausing an intense pressing drill, he delivered this blunt message: “If you’re lethargic and don’t work as a team, you’ll get fuck all.”

Advertisement

During his first pre-season with Newcastle, Howe needed to ensure the players fully understood what he required. After years of low-block defending and counter-attacking, Howe wanted to turn Newcastle into a high-press, front-foot side — and the rapid sea change has been staggering.

Under Steve Bruce, Newcastle were the Premier League’s most passive team; in November 2020, their pressing statistics were the top flight’s lowest for five seasons.

Contrast that with 2022-23, when no team has regained possession in the attacking third more frequently than Newcastle — an average of 6.8 occasions per 90 — nor won as many high turnovers ending with a shot (17), which are sequences that start in open play and begin 40 metres or less from the opponent’s goal.

Saturday’s 5-1 victory over Brentford was the ideal demonstration of Newcastle’s fresh approach, with three goals as a result of stealing the ball inside the opposition half. It was a planned tactic, with players pressing whenever David Raya, the goalkeeper, was looking to go short.

But it is not only Brentford who Newcastle have looked to smother high. Visitors to St James’ have ceded possession in their own defensive third an average of 8.2 times this season.

Repeatedly, Bruce insisted that Newcastle’s identity had to be to “defend deep and hopefully counter” because “that’s the only way we can play”. Yet Howe has instilled the mantra of “intensity is our identity” at Newcastle — repeating it before almost every session and plastering it on the walls at the training ground.

The transformation is striking and encapsulates the change at Newcastle post-takeover.

Before Howe, Newcastle were simply not a pressing side.

One measure that indicates how a team operates off the ball is the number of opposition passes allowed per defensive action (PPDA). The lower the PPDA, the higher the intensity with which a team is trying to reclaim possession.

The graphic below, across a 10-game rolling average since the start of 2019-20, shows Newcastle have become far more active off the ball, with a sharp increase this season.

Newcastle were at their most passive in 2019-20, averaging a PPDA of 19.4 during Bruce’s first full season, then 18.3 in 2020-21.

Bruce claimed the players had a “certain way drilled into them” by Rafa Benitez, his predecessor. While Newcastle did defend with a low block under Benitez, they dropped even deeper and became more passive under Bruce.

Advertisement

In a 4-3 home defeat to Manchester City in 2020-21, Newcastle’s PPDA was 51.2 and they did not win a single final-third turnover. During a smash-and-grab 2-0 win at Sheffield United in 2019-20, Newcastle’s PPDA was 53.8 and they did not once claim possession in the opposition third.

An example of how Bruce’s Newcastle would often let the opposition play out from the back is shown below, in the final match pre-takeover, a 2-1 defeat at Wolverhampton Wanderers.

Wolves have possession in their box but, rather than advance towards the opposition, Allan Saint-Maximin and Miguel Almiron backtrack.

Wolves play across their defence and into the opposition half before any Newcastle player engages.

When Newcastle did press under Bruce, some players felt there was a lack of detail provided as to how they would approach it tactically. That sometimes led to players pressing alone with no support.

Here, in a prime example, Saint-Maximin is seen sprinting forwards alone during that Wolves defeat.

Last season — during which Bruce oversaw eight matches, Graeme Jones three and Howe 27 — Newcastle’s PPDA reduced to 15.3. That, however, is skewed by Bruce and Jones.

During Jones’ spell as caretaker, Newcastle’s average PPDA was 22.9. During a 3-0 home defeat to Chelsea under Jones, Newcastle allowed Chelsea to have possession for 50 seconds without engaging.

The visitors started inside their own box, but instead of pressing, Newcastle’s forwards retreat to halfway, allowing Chelsea to move possession down the right.

Chelsea switch play to the left as Newcastle drop deeper.

Eventually, the ball shifts back to the right and Hakim Ziyech whips in a cross without a single challenge being attempted.

Under Howe last season, Newcastle’s PPDA was already trending downwards — meaning they have become more intense at pressing — but this season it has dropped by a third on last season’s average to 10.2. The only time it has gone above 13 was away at Liverpool (20.7).

From being the least-intense pressers in the Premier League across multiple seasons, Newcastle are now the fourth-most active side off the ball.

During 84 league matches under Bruce, Newcastle’s PPDA dipped below 10 in four matches. In the nine games this season, Newcastle have already recorded a PPDA lower than 10 on five occasions.

“They’re very impressive,” Thomas Frank, the Brentford head coach, said. “They’re a very aggressive and front-foot team. I like the way they play.”

The out-of-possession approach of this Newcastle side is simply incomparable to its previous incarnation.

How has Howe managed to effect such a seismic shift so swiftly?

“It’s a very gradual process,” Howe tells The Athletic. “The execution and actual introduction of that idea takes time because it’s not just a switch you can turn off and on. It’s daily habits, repetitively immersed in the players. That’s what you have to do. One day is not enough, a week’s not enough, a month’s not enough. You need to drill down with the players all the time: ‘These are my expectations, these things are what I want’.

Advertisement

“Sometimes that takes maybe a change of personnel to make that happen as well. Slowly but surely we’ve got there and I think we’re growing that side. But nothing comes easy. It’s consistent messaging from me and the coaching team to the players to try to bring that on.”

When Howe arrived last November, he wanted Newcastle to evolve, but he recognised he could not rush change. The players were not deemed physically capable, never mind tactically prepared, to carry out his gameplan. After joining in January, Matt Targett admitted he took time to adapt to the intensity of sessions; during Howe’s first fortnight, Jonjo Shelvey went to bed at 8pm every night due to exhaustion.

Steadily, as fitness improved, Howe introduced more off-the-ball alterations so that by the end of last season Newcastle were playing with a higher defensive line and pressing well as a unit.

It took a gruelling pre-season to finally bring Newcastle’s players physically and tactically up to a level that would allow for Howe’s front-foot philosophy to thrive. Howe wanted Newcastle to improve in all departments so that no other team could outlast his own.

Data collected by Newcastle’s analysts show the squad is fitter than ever — and that has been evident in the ferocity and volume of their pressing. Beyond PPDA, Newcastle’s high regains have also increased significantly, shown by the graphic below, which charts a 10-game rolling average of their possessions won in the attacking third from the start of 2019-20.

Under Bruce, Newcastle won the ball in the opposition third 2.8 times on average per game; this season, that is up to 6.8.

Against Nottingham Forest, Newcastle overturned possession 12 times in the final third.

In total, Newcastle have already stolen the ball 61 times in the opposition third in 2022-23, as the graphic below shows. The one occasion inside the box was Almiron’s opportunistic goal against Brentford.

As the graphic below shows, Newcastle are regaining possession far higher this season and in wider areas than in previous campaigns.

Against Brentford, Newcastle only made five turnovers in the final third but demonstrated the power of a coordinated, well-practised press.

For Murphy’s goal, Josh Dasilva’s overhit pass to Kristoffer Ajer was the trigger for five Newcastle players to press.

Ajer passes to Raya, who Murphy sprints towards, closing off the return ball.

Raya thinks Mathias Jensen is his out ball, but Wilson has run into the space Murphy has vacated and nicks possession, before teeing up his team-mate.

Guimaraes’ second goal, meanwhile, typified Newcastle’s desire to regain possession quickly.

Shandon Baptiste attacks down the right, tracked by Dan Burn, while other Newcastle players follow.

When a combination of Murphy and Guimaraes win possession, three other Newcastle players are in close proximity, compared to Baptiste’s two Brentford team-mates.

Few teams outside the so-called “Big Six” are willing to play through Newcastle’s press and, when they do attempt it, as Brentford did, they can become unstuck. But when sides go long instead, Newcastle often regain possession inside their own half anyway, with their high line forcing opposition forwards deeper.

Advertisement

This, and Howe’s desire for Newcastle to retain the ball, explains their rise from the third-lowest average Premier League possession in 2021-22 (39.3 per cent) to the sixth-highest this season (52.9 per cent).

It is not that Newcastle press all the time, though. There are specific triggers, which differ depending on the opponent.

Against Bournemouth, like Brentford, passing back to the goalkeeper was one. Here, Alexander Isak immediately rushes Neto, while four team-mates also advance.

Bournemouth complete two passes but can only play it to the right-back position before Guimaraes turns the ball over.

Newcastle’s pressing is still a work in progress — given the forward line is pretty much the one Howe inherited — though Newcastle’s improvement has already been stark.

“I think a lot of that comes down to the players you have. They make the system and the gameplan,” Howe said. “I think we have a few players that are very good athletes; their first instinct is to press. Probably somebody like Miggy would fit perfectly into how we want to play off the ball. Certain other players might need work to deliver it. That’s something we’ve invested in.”

Willock’s dynamism is key to Newcastle’s press, as is Longstaff’s work rate. Bayern Munich head coach Julian Nagelsmann described Joelinton as an “animal” and a “machine” for his off-the-ball efforts while the two were at Hoffenheim. While Isak’s pressing was praised in scouting reports.

Perhaps only Saint-Maximin is ill-suited to pressing among Newcastle’s forwards, though Howe worked with the Frenchman during pre-season to ensure he “is able to deliver the physical effort I want the team to deliver”. Joelinton is deployed behind Saint-Maximin because the Brazilian is able to cover for his team-mate’s lack of defensive intensity.

Advertisement

Almiron, though, has been described behind the scenes as pretty much Howe’s ideal off-the-ball player.

The Paraguayan’s endurance and pace off the mark mean he can press both in a unit or as an individual.

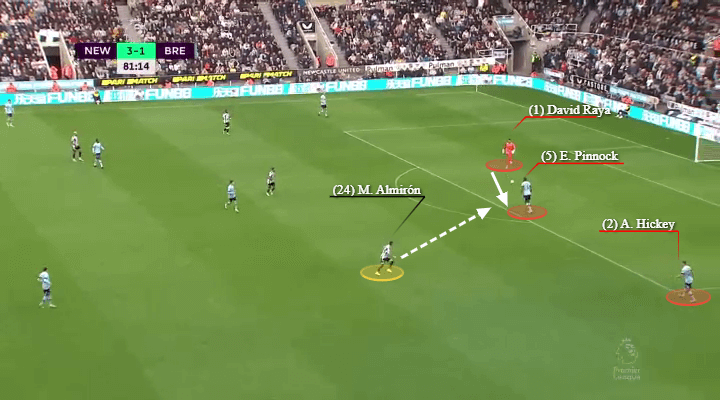

Against Brentford, none of Newcastle’s forwards are pressing when Raya receives a pass.

Raya passes to Ethan Pinnock, with the defender facing away from Almiron, who sprints at that moment.

Only spotting Almiron late, Pinnock underhits a blind pass back to Raya, allowing the Newcastle forward to score.

Howe wants his team to be brave against all teams, however, and they were particularly bold against Manchester City.

One example saw Kieran Trippier harry Joao Cancelo on the edge of the Manchester City box, with five Newcastle players following.

Cancelo’s panicked clearance goes straight to Almiron, who has team-mates in and around the box.

It was one of nine turnovers Newcastle made inside Manchester City’s final third and it underlines their newfound gameplan. Their pressing stats are significantly higher at home than away, which is to be expected, though Howe is keen to continue the evolution.

“We’re trying to change,” Howe told Alan Shearer when discussing Newcastle’s approach. “It’s got to be gradual, but we’re trying to implement a style where we’re progressive and dominant and going home and away to attack the game.”

The intensity of Howe’s training sessions are unlikely to drop any time soon as he strives for high-octane football.

(Top photo: Visionhaus via Getty Images)