The Athletic has live coverage of Oregon vs. Washington in Week 7 college football action

Editor’s note: This is part of a series of stories about innovation and change in college football throughout the 2023 season.

It was around this time last season when Tennessee’s fast-paced offense was all the rage in college football, from quarterback Hendon Hooker’s big arm and downfield throws to receiver Jalin Hyatt’s speed in space. Fast forward a year, and the offense taking college football by storm belongs to Washington.

Advertisement

The difference in numbers between these two systems is substantial: Washington leads the country in producing 569.4 yards per game, 446.4 of those coming through the air. That is 44 more total yards per game and 120 more passing yards per game than the 2022 Vols. Washington is also averaging a national-high 8.8 yards per play after Tennessee finished at 7.2 last year.

And the difference in philosophy is clearer: The Huskies’ offense is built not on explosivity, but on efficiency. The explosive plays are a direct result of the efficiency. And they’re doing so with little reliance on the run game. Washington’s 123 yards rushing per game rank 102nd nationally. The last time the country’s top offense was ranked 100th or below in rushing? Kliff Kingsbury’s Texas Tech unit with Patrick Mahomes in 2016. Per TruMedia, Washington ranks 127th in run play percentage (38.7) and 78.4 percent of its total yardage comes from passing, the sixth-most.

It’s no secret what Washington wants to do behind quarterback Michael Penix Jr. as the No. 7 Huskies prepare for their biggest game yet against rival No. 8 Oregon on Saturday afternoon.

“For Tennessee, it was about their speed and their spacing, so when they make you miss it’s a home run,” said an opposing defensive coach familiar with both the Vols and Huskies, speaking on the condition of anonymity so he could candidly discuss other teams. “But Washington doesn’t want to run the ball. It’s not their priority. They are all about protecting Penix and silently picking you apart in the pass game.”

The Huskies’ offensive innovation lies in their efficiency and simplicity. The operation is built on one core philosophy: creating space to exploit the one-on-one advantage. It is able do that schematically in three distinct ways:

- Creating horizontal stretches on underneath defenders

- Creating vertical stretches on deep defenders

- Mastering individual route technique

Before we get into schematics, let’s first address the obvious: Penix is one of the nation’s best quarterbacks. Through five games, he leads the county in passing yards per game (399.8) and yards per attempt (11.2) and ranks third in passing touchdowns (16). The Indiana transfer’s processing time is off the charts, which allows him to distribute the ball quickly to a deep receiving corps.

Advertisement

Now the not-so-obvious: The Huskies’ offensive line is outstanding. Center Parker Brailsford, guards Geirean Hatchett and Nate Kalepo and tackles Troy Fautanu and Roger Rosengarten may not all be names thrown around frequently in NFL Draft circles, but together they have been fantastic in protecting Penix. They have surrendered only three sacks all seasons in 202 dropbacks. Per TruMedia, Washington ranks third in both pressure rate and sack rate allowed.

Schematically, the Washington system is grounded in the Air Raid style. It’s something head coach Kalen DeBoer has cultivated in his previous stops at Fresno State, Indiana, Eastern Michigan and Southern Illinois. His first hire at Washington was offensive coordinator Ryan Grubb, who came with him from Fresno State. While the system has always been efficient, it has exploded thanks to the intelligence and comfortability of Penix, who worked with DeBoer at Indiana.

The final piece of the Huskies’ offensive triumvirate has been the addition of wide receivers coach and pass game coordinator JaMarcus Shephard. Shephard, a former Mike Leach disciple, came over from Purdue, where as the co-offensive coordinator he helped catapult the Boilermakers to the fifth-highest passing offense in the country in 2021 alongside Jeff Brohm. The preciseness with which Shephard demands his receivers run routes is quite remarkable and something I’ll explore later.

GO DEEPER

Washington's star wide receivers enjoying 'once-in-a-lifetime experience'

Horizontal stretches

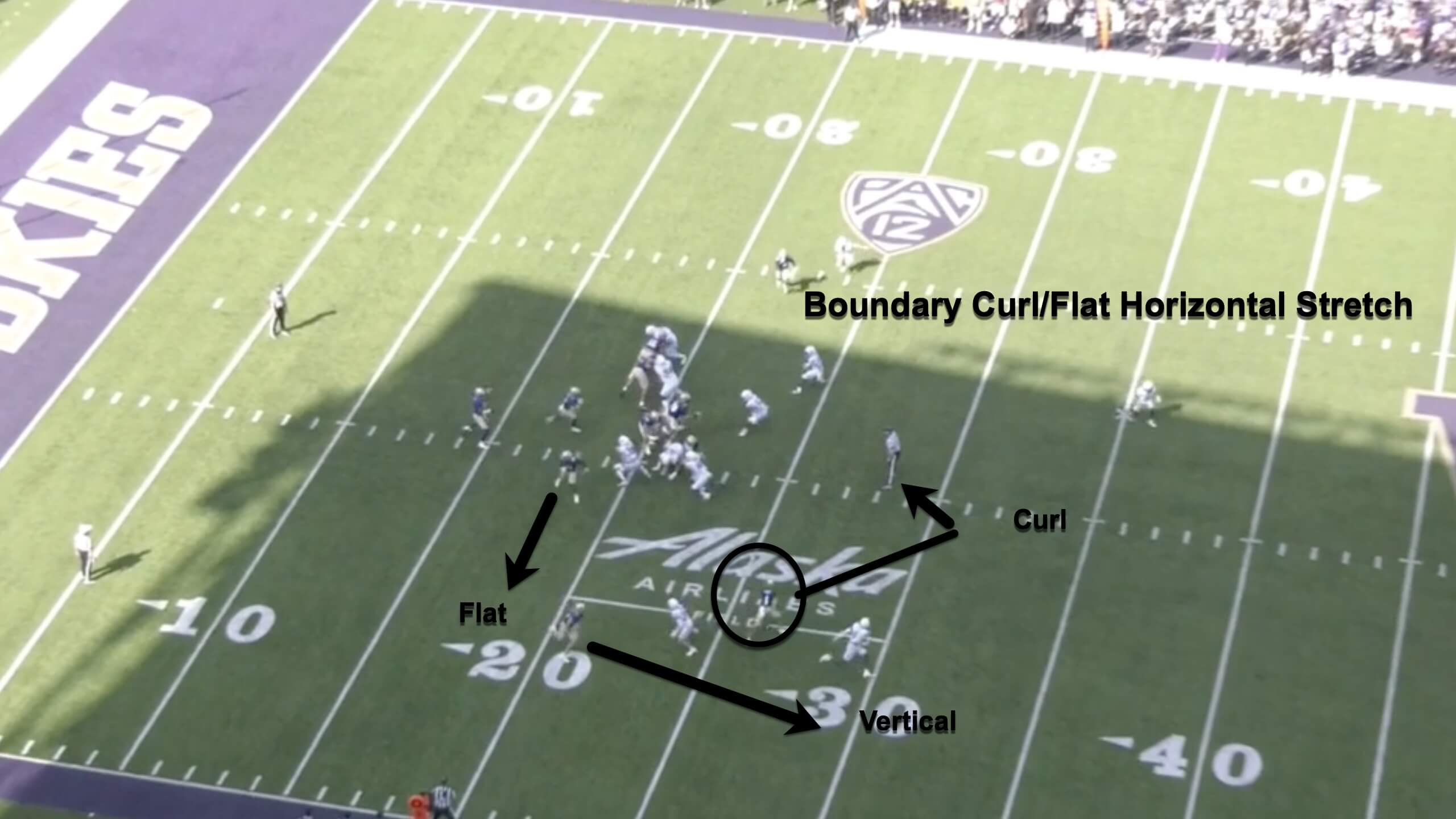

The first hallmark of any Air Raid system is horizontal stretch concepts that place underneath coverage defenders in a bind. These concepts can be packaged as either curl/flat combinations that manipulate outside linebackers or high/low combinations that manipulate corners. These are staple concepts against a one-high safety defense, which is a coverage that the Huskies surprisingly see on almost 70 percent of snaps, according to TruMedia.

While most teams like to run these stretches to the field, Grubb and Shephard design them into the boundary. They will often use the back to place the horizontal stretch on the outside linebacker, opening up the curl window for receivers like Rome Odunze, who is brave enough to occupy the middle of the field. In the image below, the No. 2 receiver runs a vertical stem to occupy the corner. Quite simply, if the outside linebacker plays the running back, it opens up the curl window for Odunze.

The next image is the same concept, but now the horizontal stretch is placed on the outside linebacker, who has to make a decision to play the wheel route by the tight end or the back in the flat.

In the clip below against Boise State, the outside linebacker chooses to play the flat, opening up the wheel route for tight end Josh Cuevas and a Washington score.

It’s a simple build-in for the Air Raid system and an easy read for Washington.

Several weeks later, Grubb used the same concept against California, again into the boundary. And when the outside linebacker chases Odunze into the flat, it opens up the curl window for the receiver and the Huskies convert on third-and-long.

When Grubb and the staff choose to stretch the field-side flat defender, they prefer to run what’s known as extended “snag” concepts, which are three-man route combinations consisting of a flat threat, a vertical threat and an intermediate threat in the curl window.

In the clip below against Tulsa, the curl/flat defender gets absorbed by the curl of the No. 2 receiver, opening up an immediate throw to the flat for running back Will Nixon and a big gain.

Arizona played a Drop 8, three-high safety defense against Washington, so Grubb extended his curl routes to deeper, 15-yard break points.

In the image below, Washington runs a double curl concept from trips, where the outside curl manipulates the curl/flat defender to open up the window for the inside curl in front of the high safety and a big third-down conversion.

Vertical stretches

In the Air Raid system, vertical stretches are designed to manipulate third-level defenders such as safeties. Contrary to the popular “just go deep” belief, there is an art form to affecting high-safety coverage. Washington does it better than anyone by perfecting precise route technique, which I will explain later.

Advertisement

One of the most common routes to take advantage of single-safety defense is the post route. The Huskies are among the best at utilizing it. The post is designed to manipulate a single high safety. Most programs will teach the post route to cross the toes of the high safety, but Shephard does a great job of having his receivers run to space in zone coverage.

And in the clip below against Boise State, receiver Germie Bernard works across the high safety all the way to the opposite hash to catch a ball that only Penix can place there.

Michigan State mistakenly played Washington in predominately single-high defense for most of their game, and Penix torched the Spartans for 473 yards in the air, mainly on these post concepts. The clip below is a perfect strike to Ja’Lynn Polk that put the Huskies inside the 10-yard line.

Where Grubb and the offensive staff gets creative is by utilizing double-post concepts to the field, which now places extreme stress on the single high safety, who cannot play both routes. It’s an easy read for Penix, who will throw away from the action of the safety.

In the clip below against Boise State, the high safety elects to play the intermediate post route, opening up the secondary post behind it for an easy score.

And when defenses start to rotate into two-high coverage structures, Grubb and his staff build in sail concepts (deeper outs) to take advantage of the space vacated by post routes.

Masterful individual route tech

Quite simply, the Washington receiving corps knows how to run away from leverage. Odunze is third in the country in receiving yards per game (121.6). Polk averages 93.6 yards per game. And though Jalen McMillan — who joined Odunze in the 1,000-yard club last year — suffered a lower-body injury in the first half against Michigan State, he’s expected to return for Saturday’s game against Oregon.

Advertisement

There is a coaching maxim that says, “You’re either coaching it or letting it happen.” And when watching the film, it’s clear that Shephard is coaching it. Shephard obsesses over yards after catch potential in his unit and he teaches them to be “takers” of the football by having them be proactive in going up and snatching the ball.

Shephard teaches his receivers to attack the ball on post routes by taking the ball out of the air rather than allowing it to come into their bodies.

Case in point: Michigan State. After burning the high safety on post routes, Polk transitions into running a “cop” (corner/post) route to attack leverage where it’s given. In Washington’s system, it’s a clear adjustment that Penix is aware of. He delivers the ball perfectly at the break point.

Even in the clip below to the boundary, Polk runs the corner route directly away from the leverage of the safety. Penix delivers the ball in the only spot where he can: between the numbers and the sideline. Not many quarterbacks have the ability to do that.

The same fundamentals are taught to outside receivers. In the clip below against Cal, Odunze runs a simple go route to the field but cuts his split enough that he can attack space away from the corner. Again, the ball is delivered perfectly.

Can Oregon slow down Washington?

This Saturday, the challenge will be on the Oregon defense to take away space for these receivers to work. The Ducks are sixth in the country in total defense and fifth in scoring defense, allowing only 11.8 points per game. Last year, Penix threw for 408 yards against the Ducks in a 37-34 Washington win in Eugene.

To defend the Huskies this time, the Ducks will need to do something many other opponents have not done and play two-high safety defense. Oregon has played two-high on 33 percent of snaps so far this season. Expect more of it Saturday in Seattle.

Advertisement

The Huskies have seen two-high coverage on only 23 percent of snaps, according to TruMedia. Tulsa was the only opponent to have its safeties align at 15 yards, but it didn’t have the personnel to match up with the Huskies’ receivers. The Ducks may just have the secondary to match up with the Huskies receivers, at least better than most. They relied on their back end to stymie Colorado’s pass game in September, limiting quarterback Shedeur Sanders and his receiving crew to 159 yards, their lowest output all season.

The Ducks will need a repeat performance against a more talented unit in order to steal the win in Washington, which has looked as unstoppable as any offense in the country thus far.

GO DEEPER

Kalen DeBoer in his own words: Defining his culture, his leadership, and life lesson

The Innovation & Change series is part of a partnership with Invesco

The Athletic maintains full editorial independence. Partners have no control over or input into the reporting or editing process and do not review stories before publication.

(Top photo of Michael Penix Jr. and Ja’Lynn Polk: Steph Chambers / Getty Images)