There is more scrutiny on referees than ever before.

Their decisions have always been the subject of debate with officials the target of abuse, but typically those complaints would be confined to fans, players on the pitch and the occasional post-match complaint from a manager. Now, though, it feels more institutional.

Advertisement

The introduction of video assistant referees to the Premier League in 2019 feels like a demarcation point.

There was an idea that the use of technology in officiating would eliminate errors, and nobody would have cause for complaint. That has not been the case.

Although many errors have been caught and the number of accurate decisions has increased, the anger at the smaller number of inaccurate decisions — at least those that have been perceived to be inaccurate — has intensified. Every decision is scrutinised over and over on TV, websites and social media and, as such, their importance becomes inflated. The VAR system may have reduced the number of mistakes, but the errors that remain have been amplified.

For example, this season has seen a marked increase in the number of clubs outwardly and officially complaining about their treatment at the hands of referees. Arsenal wrote to the Professional Game Match Officials Ltd (PGMOL), the body responsible for officiating in England, after they believed a goal was incorrectly given against them in their defeat to Newcastle United in November. Liverpool released an angry statement after the VAR debacle in their defeat to Tottenham Hotspur in September. And Nottingham Forest have written to PGMOL three times over assorted adverse decisions.

This is on top of the managers who consistently bring up decisions made against their team, including but not limited to Jurgen Klopp, who among other things got a two-match ban last season for saying he doesn’t know “what Paul Tierney has against us”; Vincent Kompany, who said earlier this season that Burnley have a “tough relationship” with referees; and Chris Wilder, who described referee Tony Harrington as giving “yet another ridiculous performance”, after which he accused an assistant of being disrespectful by eating a sandwich.

Advertisement

The question is: why do they bother? What is the actual motivation for the increased complaints? And is it going to change anything?

The answer to the last question is pretty difficult to answer with any real certainty. What is certain is that more clubs are doing it. PGMOL has seen an increase in what we’ll call ‘discussions’ between themselves and aggrieved clubs, although that is at least partly because they — or, more specifically, Howard Webb, who rejoined the group as chief refereeing officer in 2022 — have encouraged clubs to engage with them when they feel aggrieved.

In some instances, where a blindingly obvious error has been made, Webb won’t wait for the club involved to initiate contact: he will proactively contact them.

But in some less obvious cases, the club will provide their own ‘feedback’ to PGMOL. This sometimes comes in the shape of writing a formal letter, as we know Arsenal and Forest have done, making sure the public knew about their grievances. When a letter is received, Webb and other refereeing analysts assess the claims and respond accordingly, and provide explanations where requested. On some occasions, Webb will meet the club for a more thorough debrief.

More often than not, it’s much less formal and usually takes the form of phone calls between Webb and the clubs. Broadly speaking, with some exceptions, relations between PGMOL and the clubs are better than the public perception might suggest, according to a source close to the situation, who did not wish to be named to protect relationships.

Even with that in mind, there is the question of why clubs are doing this. The official line from some of the more prominent teams involved is that they are merely seeking clarity about why certain decisions are made, to ensure that an open dialogue is maintained and to essentially remind referees that they are keeping an eye on standards. Who’s watching the watchmen? The clubs, it seems.

Advertisement

All of which is undoubtedly true and even commendable: constructive criticism is important and can help make the game better. But all that would be possible without some clubs ensuring that it is made public, which usually takes the form of careful briefings to the media, or in the case of Arsenal after the Newcastle incident, releasing a statement in which they referred to “yet more unacceptable refereeing and VAR errors”, and said that “PGMOL urgently needs to address the standard of officiating”.

Club statement

— Arsenal (@Arsenal) November 5, 2023

There are a variety of motivations for this sort of thing. It could just be an expression of frustration, a more formalised version of fans in the stands screaming at a referee. It could be an extension of the bunker mentality that many teams try to foster, the ‘us against the world’ idea: Arsenal’s statement after the Newcastle incident, when they said they “stood behind” Arteta after his post-match press conference, was a perfect example. It could be an attempt to curry favour with the fans, sending a message that they are fighting against the great injustices that have befallen them.

It could just be about perceived victories. After referee Rob Jones was involved in two controversial incidents against them, Forest requested in December that he should not officiate their games. It’s only been a couple of months, but Jones hasn’t been involved in any of Forest’s games since then. PGMOL will deny that it is being dictated to, but Forest might be able to claim this as a win.

Plenty will also have no real strategy to it at all, particularly when it’s just a manager teeing off to the media after the game: that is just a frustrated man lashing out, with probably no higher purpose in mind.

Misdirection is another motivation — the best way for a manager to distract attention away from a poor performance is to highlight an adverse decision.

It could also be about trying to exert influence, to lean on the collective consciousness of referees by playing up the idea that the club in question is being treated unfairly. They will know it’s unlikely to result in referees consciously trying to ‘balance things out’ by giving more decisions in that club’s favour, but on a subconscious level it might be possible to implant the idea that referees should think a bit more carefully when a tight decision comes up.

Naturally, the idea that referees can be influenced in any way gets pretty short shrift. PGMOL provides advice and training to referees in this area, and insists referees are simply conditioned not to bow to such pressure, wherever it comes from. The idea is that they are simply wired differently from the rest of us, inured from pressure by years of fans screaming abuse from the stands.

“I can only speak for myself and say it would never bother me,” former Premier League referee Mark Halsey tells The Athletic, when asked if such tactics could influence an official.

“I would only ever referee what was in front of me. You cross the white line and see 22 players. They all knew what they were getting from me. I wouldn’t have a problem with what had gone before. That’s what you’re trained to be. You’re there to take the game on that day and engage with the players the best you can. That’s the approach I always had. That’s the shop floor.”

Advertisement

Equally, it’s impossible to rule out the idea that referees, human beings as they are, could be influenced in some conscious or subconscious way. Writing in the Daily Mail a few years ago, Graham Poll admitted some referees could subconsciously favour bigger teams, saying that they “know the fallout, from the managers and the media, if they give a soft penalty against one of the big teams and the sub-conscious mind kicks in to afford the referee a level of protection, quite naturally”. So could the public pressure, from smaller teams particularly, be an attempt to redress this?

How effective are these attempts to exert influence? One possible way to look at it might be through the VAR system. In theory, if a club is trying to exert pressure on referees, then that influence should be most keenly felt when a referee is sent over to the monitor. If the pressure is working, then a club should have plenty of decisions overturned in their favour, right?

Like every other attempt to quantify the impact of such pressure, it’s difficult to say. According to figures assembled by ESPN, Forest have had six VAR decisions changed this season, five in their favour and one against, which is the biggest net positive in the Premier League. And yet Arsenal, probably the other most vocal club, have been involved in seven VAR overturns, four in their favour and three against, giving them a net outcome of -1.

There are several clear problems with drawing any conclusions from these figures: first, it’s just about overturned decisions, so if the VAR looks at an incident and decides the on-field call was fine (or at least there isn’t enough evidence to change it), a club could still cry injustice. It’s also impossible to know the reasons for the overturns: was it because of some genius psyop in which a club has influenced the public discourse enough to affect change, or was it just because the initial decisions were wrong?

Of course, all of this is predicated on the idea that there is a problem. Because if you listen to the authorities, then everything is going pretty well.

In February, Tony Scholes, chief football officer of the Premier League, insisted refereeing decisions have never been more accurate. He cited a report that claimed 96 per cent of decisions made since VARs were introduced in 2019 were correct, up from 82 per cent before that. Eyebrows may have been raised by the fact the Premier League itself had produced that report, but it was based on the judgments of the Key Match Incidents panel.

This is an independent group introduced a couple of years ago when it was no longer deemed appropriate for PGMOL, which previously organised these assessments, to ‘mark their own homework’, that is, assess big decisions made in Premier League games and report on whether they were correct or not. It’s a five-person panel: one representative from the Premier League, one from PGMOL and the other three are a rotating cast of former players and managers.

Advertisement

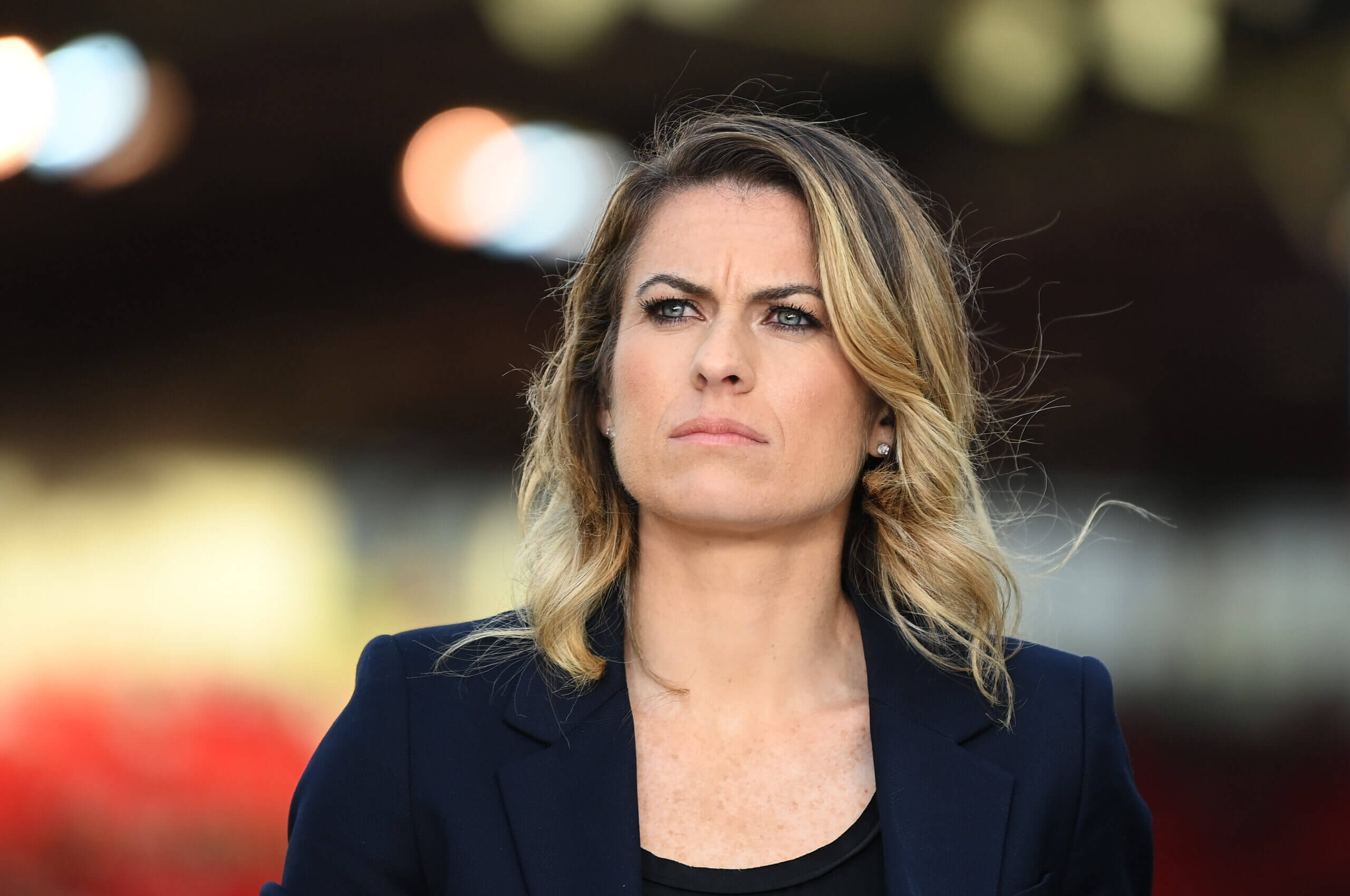

The latter group are not publicly identified, because the Premier League wants to guard against the sort of accusations of bias that will inevitably arise. However, it was reported last season that the pool included former England international Karen Carney, ex-Norwich City and West Ham United goalkeeper Rob Green, former Wimbledon manager Terry Burton, former Stoke City forward Jonathan Walters and former Republic of Ireland international Steven Reid. As you would expect, anyone who has taken on a role with a club is disqualified from being on the panel, which rules out the latter two as they have joined Stoke and Forest this season.

The panel views the key incidents from the most recent game week, they vote on whether both the on-field and VAR decisions were correct and send their verdicts to PGMOL, the Premier League and eventually the clubs. The clubs are not told who is on each panel.

Even then, it’s important to remember that, for the most part, none of these are objective facts. Most decisions are subjective interpretations of the laws, and the KMI panel are subjectively reviewing those subjective decisions. To emphasise the point, there have been occasions when, in some of his media appearances, Webb has differed in his own assessments from the KMI panel.

The problem, if you want to think of it that way, is one of perception. If you told the average fan that 96 per cent of refereeing decisions this season have been correct, they would scoff. But that is probably down to a combination of the increased highlighting of debatable decisions, and the nature of fandom: fans can’t and shouldn’t be expected to be clear-headed and objective, even logical when a contentious decision goes against their team.

Should that stop at the clubs? Do clubs, as institutions, have a responsibility to do what they can to discourage any wild conspiracy theories that inevitably grow within fan bases? Probably, but equally, they will argue they are standing up for themselves, or trying to affect positive change and the upholding of standards. This may be true to a point, but any club who insist they are nobly fighting for the greater good is insulting our intelligence: they are just unhappy when decisions go against them.

Does any of this work? It depends on how you define success or otherwise, and really it’s almost impossible to say for sure. What is possible to say, is that these positions feel entrenched now: for the foreseeable future at least, complaints are only going to increase.

(Top photo: Alex Livesey – Danehouse/Getty Images)