Gareth Southgate was always meant to represent a clean break with England’s past, a chance to draw a line under recent history and start anew. But the most alarming thing about England’s performances in Euro 2024 so far, Southgate’s fourth major tournament in charge, is how much they have fallen back into bad old habits that predate him.

There is plenty to criticise about England’s first two games in Germany — the lack of support around Harry Kane, the lack of control in midfield, the total absence of any left side — but so much of it comes back to England’s reaction to going 1-0 up.

GO DEEPER

How England's left side is undermining them with and without the ball

England scored early in both games (after 13 and 18 minutes respectively) and twice they have sat back. In neither match did they ever look like staying on the front foot and pushing to go 2-0 up. While England got away with it against Serbia, holding on to win 1-0, they did not against Denmark, being pegged back to draw 1-1.

Advertisement

Immediately after the game in Frankfurt, it was the biggest question on everyone’s lips: why did England drop so deep after going 1-0 up? Was it a tactical choice from Southgate, a way to preserve themselves, protect the lead and hit the opposition on the break? Or was it instead a subconscious decision of the players themselves, dropping deep because they did not have the confidence or energy to stick with plan A?

The Athletic attempts to find an answer…

Did England intend to drop so deep against Denmark?

It is easy to look at this phenomenon through this lens: it had to be the choice of someone to play like this, so was it the manager or the players who were at fault? Who was it whose hand pressed the ‘drop deep’ button after Kane had put England ahead?

But watching the coverage last night, you got a sense of a different explanation. What if this was not anyone’s choice but instead a technical issue, the result of England not being able to press Denmark as they wanted?

When Kane spoke to the BBC after the game, he admitted England had to “get better” at this and explained that when opponents change their shape, England struggle to press. “When teams are dropping a few players deeper, we’re not sure how to get the pressure on and who’s the one supposed to be going,” Kane said.

In his post-match interview, Southgate denied that he had told the players to play this way, making the same point Kane did, that it was a failure to press Denmark that forced England to retreat. “We’ve played teams that are quite fluid in back threes and it’s not easy to get pressure on them,” he said. “But we’ve definitely got to do better than we have done in these two matches. That’s been part of the problem. But not keeping the ball has also been part of the problem.”

It’s undeniable that England’s players look a little nervy when it comes to trying to control a match. Speaking after Thursday’s game, Kyle Walker hinted that fear of making mistakes in possession may have been a reason for the team’s regression towards their own penalty area.

Advertisement

“It’s just the game,” the right-back said. “You are sensing the game; they probably had the upper hand at certain parts of the game and as defenders you try to think, ‘What if?’.

“If we go charging forward and they go and score, all of a sudden they are blaming the defence that we are not in position.”

Whatever happens in Tuesday night’s match against Slovenia and beyond, this will now be one of the issues that defines how England do at this tournament. Every time they take the lead, the question will be how the players will react — whether they will have the courage to stick to their guns, the energy and bravery to maintain a high line, or whether they will simply shrink back into their own box. (The fact this has become the dominant narrative surrounding this England team is underlined by the fact Erik ten Hag made this point on Dutch TV after the Serbia game, accusing Southgate of “gambling with making his team compact and relying on moments” after going 1-0 up.)

Jack Pitt-Brooke

So why did England drop so deep against Denmark?

Sitting back isn’t necessarily a bad thing. In fact, at the 2022 World Cup, semi-finalists Morocco ranked first, runners-up France ranked second, and winners Argentina fourth for the highest proportion of defending time in a mid-block. What is problematic is sitting back without an effective pressing strategy to make regains (and counter-attack) or push a team backwards, then step up to press.

Serbia and Denmark might have played similar shapes (3-4-3) but progressed the ball in different ways. Serbia left out No 10 Dusan Tadic and opted for a combative, physical midfield three, which forced them to attack almost exclusively through crosses — when England defended those, they had little plan B.

Meanwhile, Denmark were more varied, attacking off transitions and playing through the thirds while maintaining a crossing threat. England’s problem was how they pressed Denmark’s wing-backs.

Advertisement

Down England’s right, winger Bukayo Saka dropped in, allowing Kyle Walker to stay narrow and defend the box. However, England’s left side was not the same. Left-winger Phil Foden stayed high to press right centre-back Joachim Andersen, possibly to try to limit his big switches. This forced left-back Kieran Trippier out, away from left centre-back Marc Guehi. Declan Rice had to cover between those and England lost superiority in midfield.

Here is Saka dropping in to defend left wing-back Victor Kristiansen.

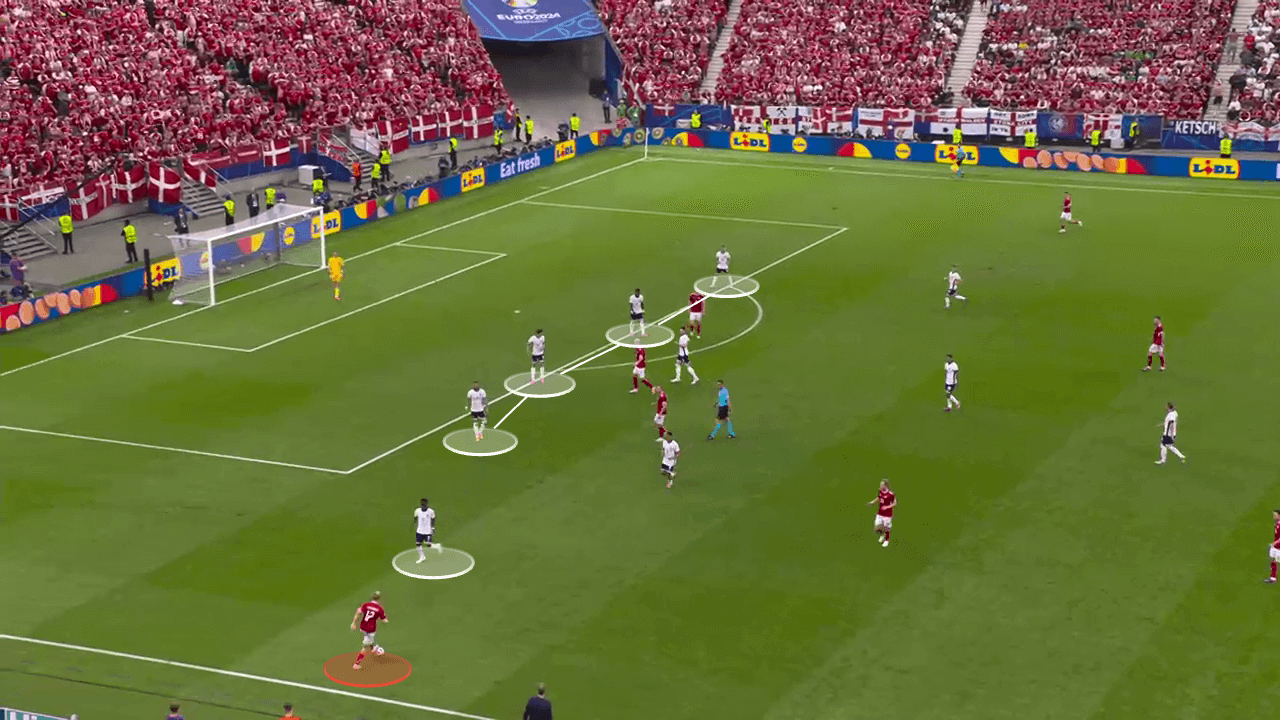

This is a typical first half example of England’s left-side issues. Notice Guehi and Trent Alexander-Arnold pointing as players jump, underlining Kane’s point about uncertainty over who should go. Foden presses Andersen, Trippier moves wide and Rice tracks Jonas Wind’s run in the half-space. Andersen passes into No 8 Morten Hjulmand and Harry Kane has to drop in to cover.

![]()

Here’s a different instance, same pattern. Kane ends up having to try to slide-tackle the pass into Hjulmand but misses it. In two passes, going out-to-in, Denmark work themselves into a shooting position. England do get bodies around the ball but can only block the shot for a corner.

![]()

![]()

England pressing in this way also explains their struggles in getting out when they did make regains. Kane, for the reasons shown above, was often not as advanced as Southgate would have wanted. It made it easier for Denmark to counter-press and keep England locked in.

The numbers make for stark reading. In terms of passes allowed per defensive action (PPDA), it was England’s second-most passive display in a major tournament game under Southgate — over 25 Denmark passes before a defensive action. Compare that to World Cup 2022, Euro 2020 and World Cup 2018, where England allowed (on average) 10, 17 and 13 passes before making defensive actions.

England’s pressing was an underrated part of their 2022 World Cup campaign and was particularly good in knockout rounds against Senegal (round of 16) and France (quarter-finals). That tournament ended with Southgate’s side second, behind winners Argentina, for final-third regains. England have made fewer than half the amount of final-third regains (per match) in Germany as they did in Qatar.

And when they do make regains, they are six yards closer to England’s goal than at the World Cup.

There are tactical justifications for England to play on the counter-attack: Kane is an excellent passer and likes to drop in; Saka, Bellingham and Foden can dribble on their own or combine and run beyond the ball. The bigger worry is that England’s counter-attack numbers have dropped as well. They aren’t threatening teams the same way France do when they sit in and then come alive in transition.

Advertisement

England have had defensive problems the entire calendar year. In the March friendly against Brazil, their high line was exposed and the counter-press was not quick or aggressive enough to prevent counter-attacks. Three days later, they struggled to deal with Belgium’s direct balls into Romelu Lukaku. And in their final friendly before the Euros, Southgate was critical of his team’s out-of-possession approach against Iceland.

Liam Tharme

Do England have a history of this?

What has been so striking to anyone with a long history of watching England is how familiar the last two games have been. This issue has not just plagued Southgate’s England but plenty of England teams from long before. There is a reason why the whole Sven-Goran Eriksson tenure was associated with the phrase “first half good, second half not so good”.

The two biggest games of the Southgate era so far have been marked by precisely this issue. First, there was the World Cup semi-final in the Luzhniki Stadium against Croatia in 2018. England took an early lead through Kieran Trippier’s free kick and actually maintained their pressure throughout a dominant first half. But in the second half, they tired, stopped pressing and dropped back. Croatia slowly seized control, equalised halfway through the second half, then won the game in extra time.

When England reconvened for their first international break after the World Cup, Southgate spoke in detail about how he wanted his England team to “develop without the ball” in future and to be more aggressive. Being able to press better was imperative.

But when England faced the Netherlands in the Nations League semi-final in Portugal in June 2019, they again took the lead in the first half, sat back, allowed the Dutch to dominate possession and were eventually picked off in extra time.

Perhaps the biggest example of this came when England faced Italy in the final of Euro 2020 at Wembley, perhaps this generation’s greatest chance to win a major trophy. Again England seized control of the game and scored early. Again they failed to score a crucial second, lost control, conceded from a set piece and then lost on penalties.

Critics of Southgate will say that he had three years to fix this issue after the last Euros and yet the evidence of Euro 2024 is that England are stuck in the same pattern. Defenders of Southgate might point out that playing this way has worked pretty well for France over the years — the kings of minimalist defending from 1-0 up — and that Southgate’s methods have worked well in the main so far.

Advertisement

But ultimately this is an issue far bigger than Southgate alone. To make it simply about him and his tactics is to ignore the proud English history of retreating with an early lead and eventually paying for it. Go back to the 2002 World Cup when England did that most notably against Sweden in the group stage, back-pedalling fast after taking the lead, and were punished for it after the break. When England were knocked out of Euro 2004 by Portugal, they took the lead after just three minutes, sat back, and after 80 painful minutes Helder Postiga scored the equaliser. Portugal won on penalties.

The game has changed a lot since then, but it was still a constant for England teams in major tournaments. Like against the USA in the 2010 World Cup, as Fabio Capello wrestled with the fact his team looked physically jaded going into a major tournament.

For a football nation that prides itself on energy and aggression, the fact England teams have been doing this for so long is fascinating. Southgate can probably not rewire national characteristics in the next week or two. But if England are not going to press high at this Euros, then they will need to find a way to defend better.

Jack Pitt-Brooke

What’s the solution?

Solving the problem is much harder than identifying it. Southgate has two options: change the personnel or change the shape. He needs to do at least one and could even do both. It was why Southgate went to a 3-4-3 against Germany in the Euro 2020 round of 16: “We wanted to be man-for-man, aggressive in our pressure. The wing-backs really did that well and set the tone.”

For all his attacking merits, Alexander-Arnold is not the type of midfielder suited to a pressing game. Rice often has to cover on his behalf and it might lead Southgate to make the switch which has been his go-to substitution in England’s opening two matches: Conor Gallagher for Alexander-Arnold.

Likewise, the high press doesn’t actually suit Kane that much, moreso Ollie Watkins. Those changes might fix defensive issues but, beyond being highly unlikely, would seriously reduce England’s attacking quality.

Advertisement

This is the crux of England’s problems. They are clear and specific but also not existing in isolation. Solving one problem might create one, or more, elsewhere. A strong defensive base has been the golden thread throughout Southgate’s time as England head coach, especially in the past two tournaments, but England need to get back to defending in the opposition half.

Liam Tharme

Additional reporting: Mark Carey

(Top photo: Alexander Scheuber – UEFA/UEFA via Getty Images)