Didier Deschamps is a glass-half-full sort of man.

France’s three goals so far at this summer’s European Championship consist of two own goals and a penalty.

But after the 1-0 win against Belgium in the round of 16, Deschamps said: “My only regret is the number of shots we had and tried to put too much power into them, and they went off target. I’m immensely proud of what we’ve done, to be in the quarter-finals again.”

Advertisement

‘Crise? Quelle crise?’

Deschamps’ critics bemoan his risk-averse tactics, defence-first approach and under-use of the immense attacking talent at his disposal. Even so, his teams score goals.

There were 10 in five games at the 2014 World Cup, his first tournament in charge. Then it was 13 at Euro 2016, 14 at World Cup 2018 and 16 at World Cup 2022, playing seven times in each competition as they got to the final of all three, winning one (2018) and losing the others after extra time (2016) and on penalties. They scored seven in their four matches at the previous Euros three years ago.

That averages out to two goals a game in Deschamps’ five completed major tournaments to date.

Part of France’s allure is a tendency to come alive in periods during games and score multiple times in quick succession, rather than dominating throughout. At Euro 2024 though, they have been uncharacteristically wasteful. France rank fifth for expected goals (xG), a measure of chance-quality, at 6.94 from their four matches, but are the biggest underperformers when it comes to finishing. They have scored only one of 10 big chances (Kylian Mbappe’s penalty in the opening group match against Poland).

Tournament | Big chances | Scored | Conversion rate |

|---|---|---|---|

Euro 2024 | 10 | 1 | 10.0% |

2022 World Cup | 21 | 10 | 47.6% |

Euro 2020 | 12 | 5 | 41.7% |

2018 World Cup | 9 | 5 | 55.6% |

Euro 2016 | 15 | 7 | 46.6% |

2014 World Cup | 11 | 3 | 27.3% |

‘Ce qui s’est passe, Didier?’

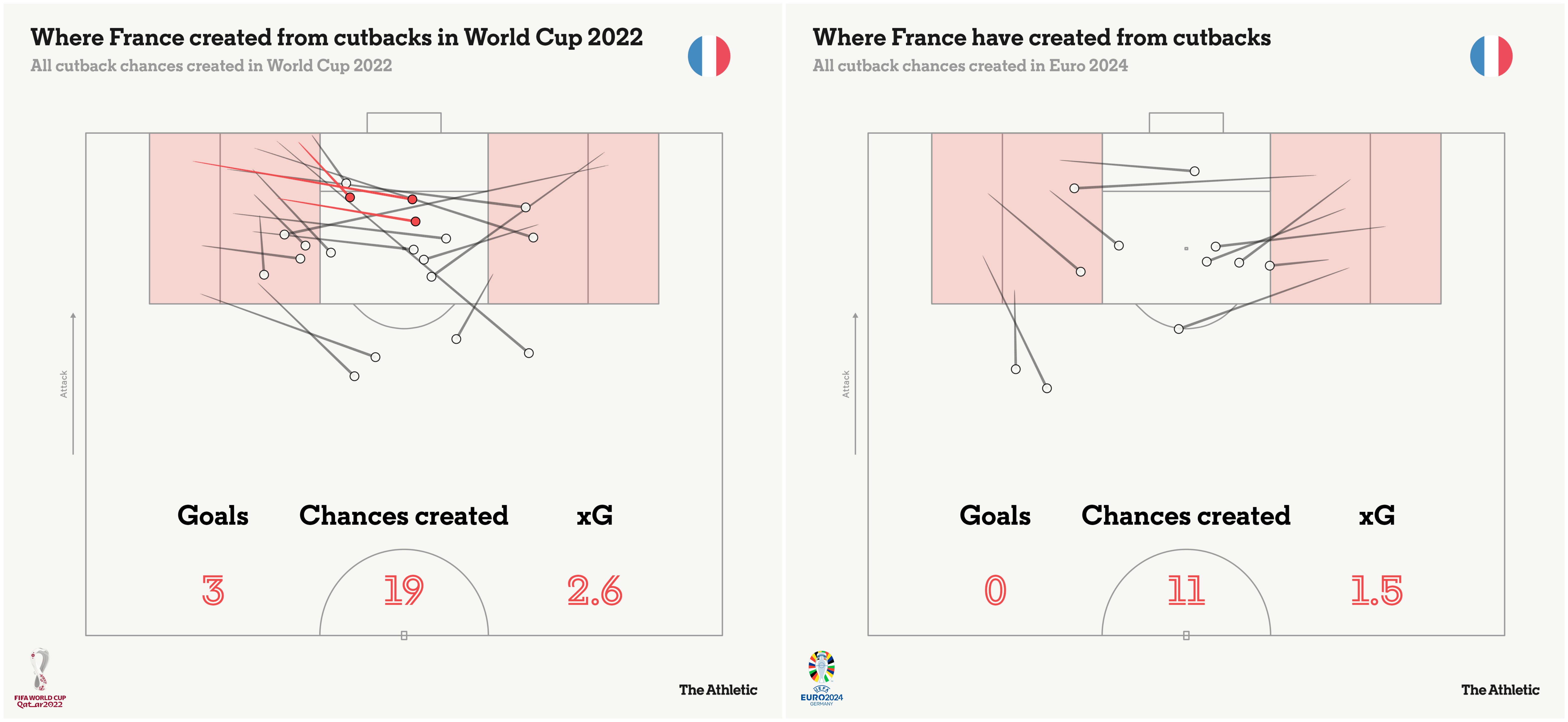

An easy (lazy) solution would be to chalk this up to variance, but watch back France’s chances, their crosses/cutbacks in particular, and consistent themes emerge.

First, they rarely get enough bodies into the penalty area. Deschamps’ midfield three of Aurelien Tchouameni, Adrien Rabiot and the recalled N’Golo Kante are about control, ball retention and defending. France have never replaced Paul Pogba’s creativity or goalscoring from that part of the pitch since his most recent cap over two years ago.

“Even though we did everything we could to score, attack and create chances, we created a lot more than Belgium,” said Deschamps following Monday’s narrow win in Dusseldorf. “But we now have the ability to control our games a little more. It’s better to have the ball, attack, and force your opponents to defend.”

Advertisement

It echoed his words after the 0-0 draw against the Netherlands in the middle group match — the first goalless game of the tournament on its eighth day: “It’s been a long time since we’ve had such control and created five or six chances. The only regret I have is that we weren’t clinical.”

He was provoked afterwards by suggestions his team were not entertaining enough for the fans in the stadium in Leipzig or the millions watching on TV back home. “If they don’t like it, they can change the channel. Not scoring is the negative point,” Deschamps said.

That draw with the Dutch typified France’s midfield profiles: Rabiot combined with the No 9, Marcus Thuram, on the edge of the box early on. After a one-two, finding himself seven yards out and with only the goalkeeper to beat, Rabiot passed sideways to Antoine Griezmann rather than trying the shot, and the chance disappeared.

Normally, Kante and Rabiot stay out on the edge of the 18-yard box when France get into cutback situations.

That could be seen in the move for their winner in the opener against Austria.

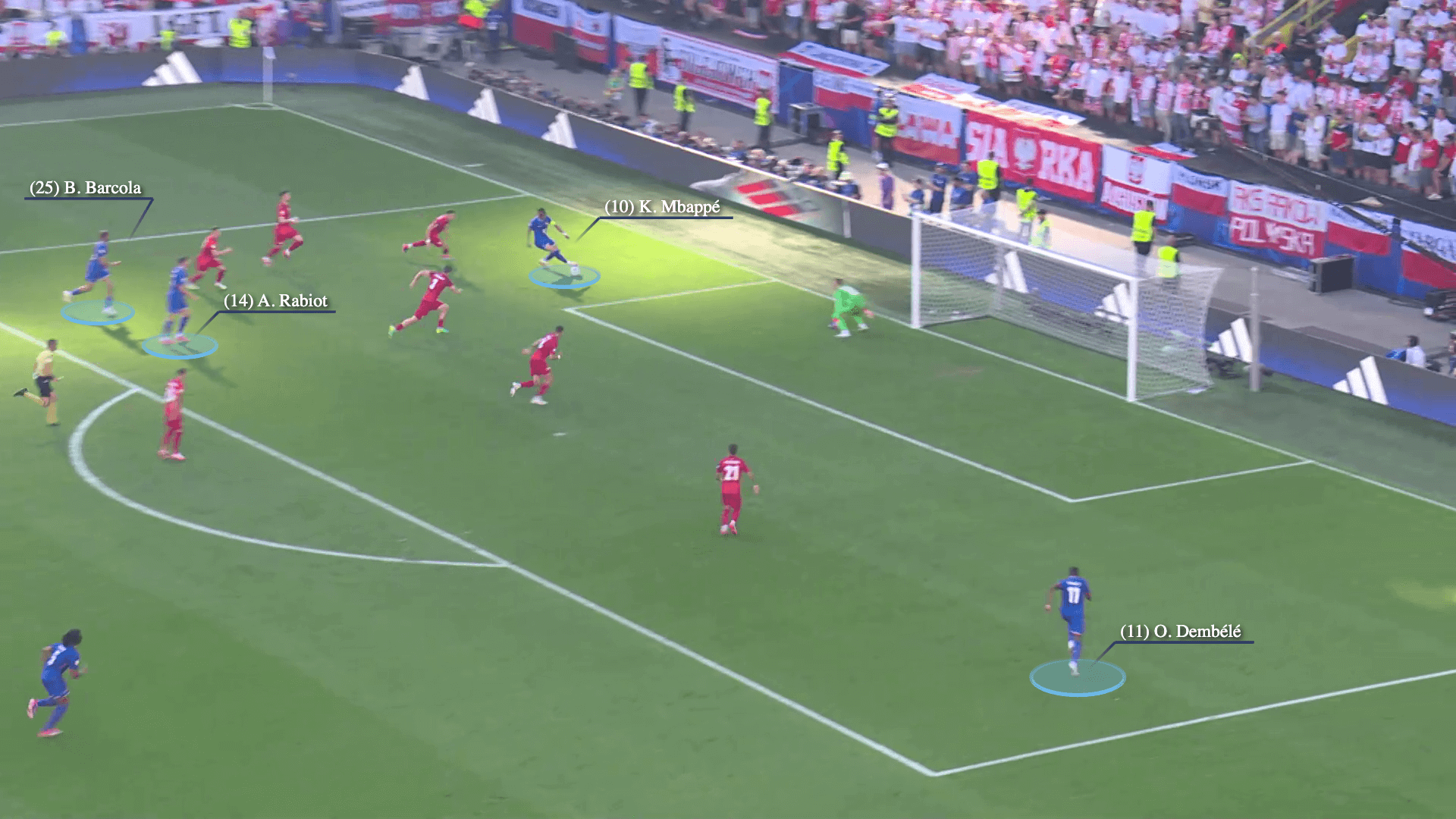

When Mbappe dribbles on the outside and crosses, Griezmann is well positioned but neither Ousmane Dembele nor Thuram is doing enough to get into a goalscoring position or disrupt the opponents’ defence.

France lack a true penalty-box No 9.

Long-time Deschamps mainstay Olivier Giroud now plays a substitute role at age 37, while Karim Benzema was picked for the 2022 World Cup after a six-year absence but withdrew due to injury shortly before the tournament and then retired from international football immediately after it. Thuram has a phenomenal attacking partnership with Lautaro Martinez at Inter Milan but is much more of a dribbler and transition player.

Deschamps has mixed between Mbappe and Thuram as the No 9 (as well as Randal Kolo Muani in qualifying for these Euros). Those two tend to drop to the edge of the box too, helping create overloads. This means France consistently get into cutback positions but don’t have players in position to attack the final ball from them.

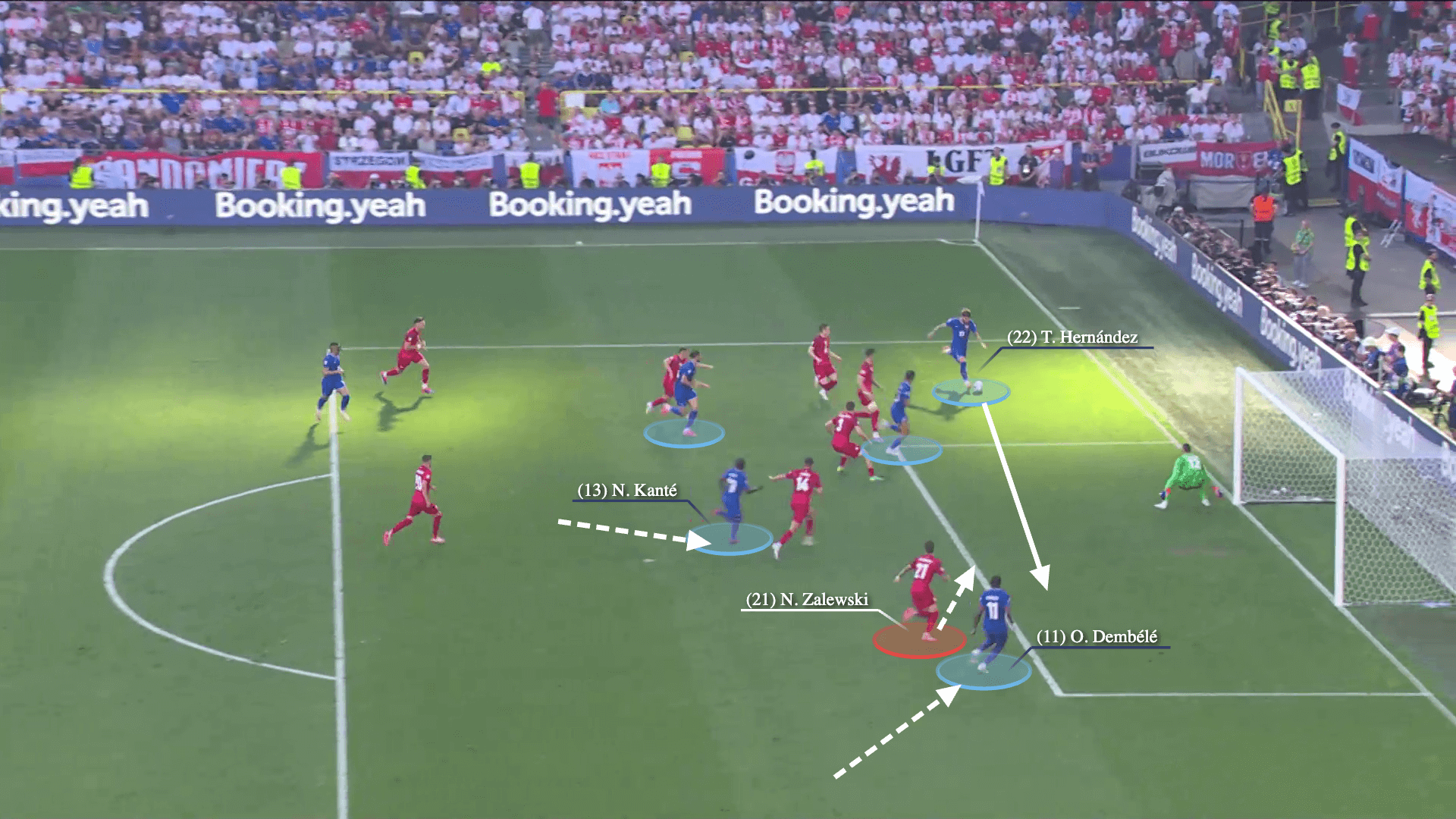

Here are two examples from this tournament, against Poland and then Austria.

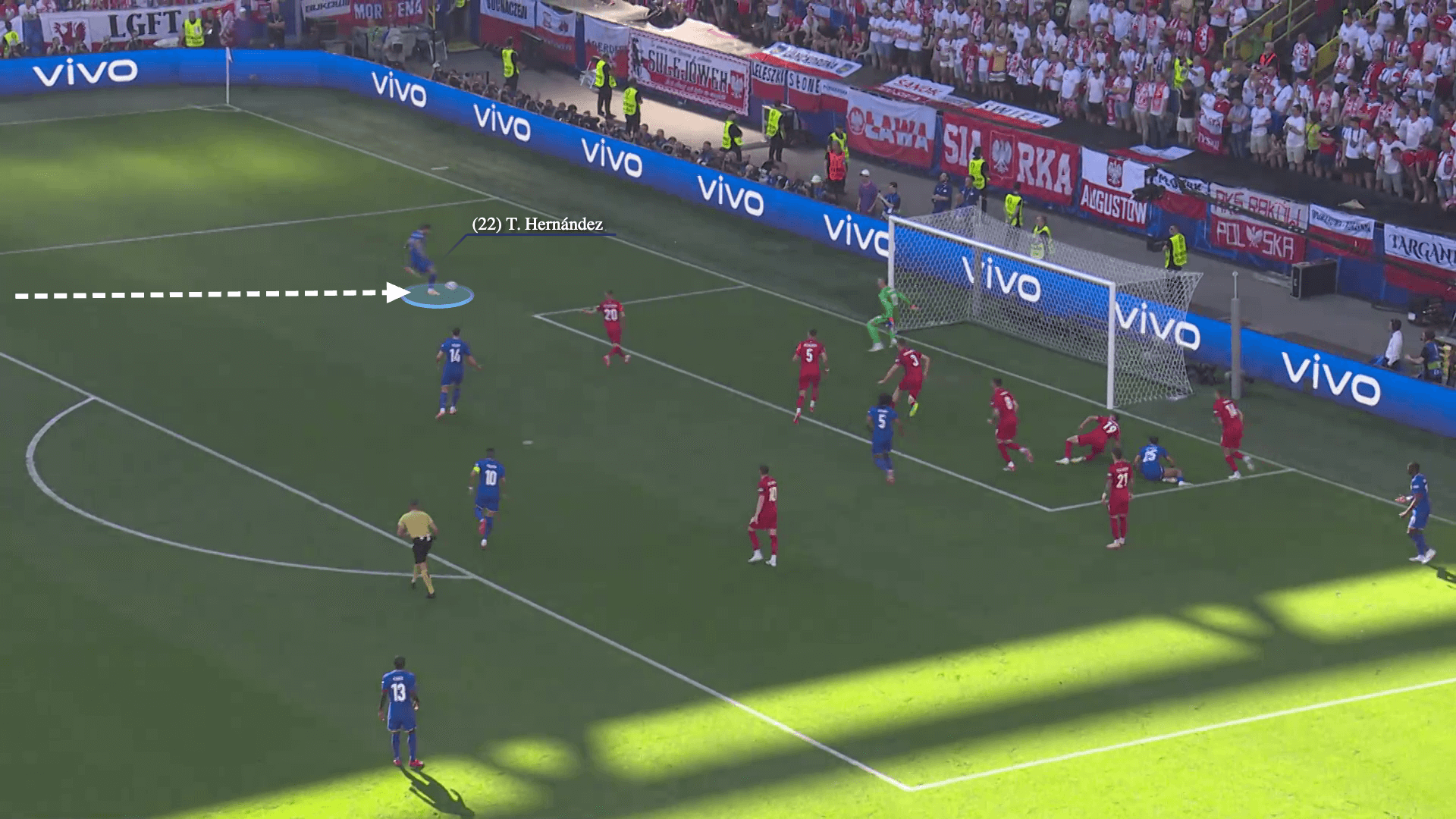

Those two examples are France attacking down their left, but they have been disproportionately creative down the opposite wing — 44 crosses from the right, 27 from the left. They have not found Theo Hernandez in-behind enough and instead, the creative burden has fallen on right-back Jules Kounde, who is a centre-back really, and is in the team for his one-vs-one defending.

France’s cutback success at the 2022 World Cup was built on putting the best passers into the best positions. Kounde has the most open-play crosses of any France player at these Euros (13); Hernandez has seven, Griezmann five.

“We wanted to take out their wingers, and this worked well,” said Belgium head coach Domenico Tedesco.

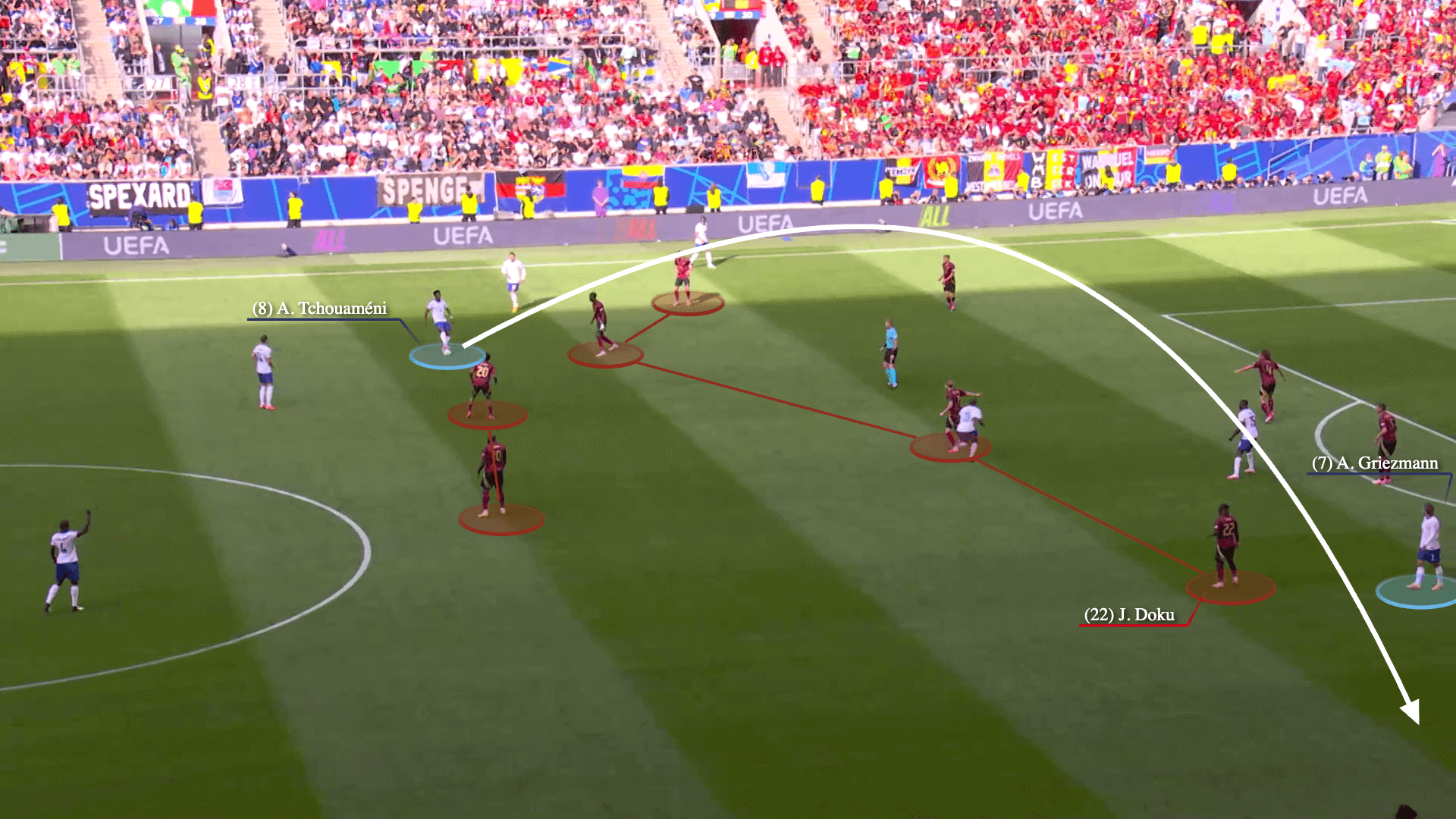

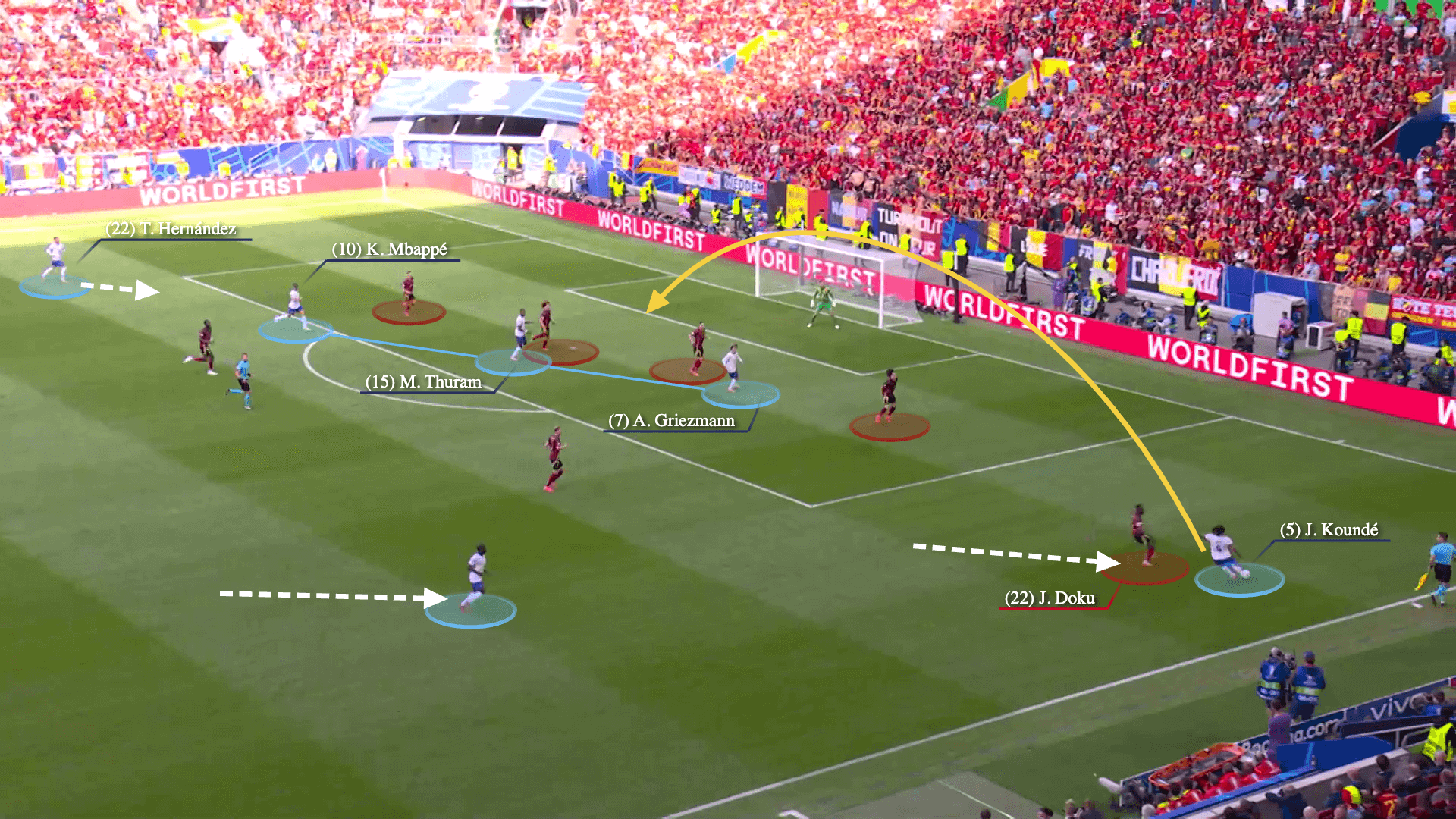

The Belgians defended in a compact 4-4-2 mid-block. France tried third-man combinations down their left, to try to release Mbappe or Hernandez, but had more joy with Tchouameni’s switches to Kounde.

Tchouameni dropped out to the left half-space. Deschamps played the versatile Griezmann as a right-winger, with his narrow positioning pinning Jeremy Doku, Belgium’s left-winger. This freed up Kounde to push on for Tchouameni’s long passes.

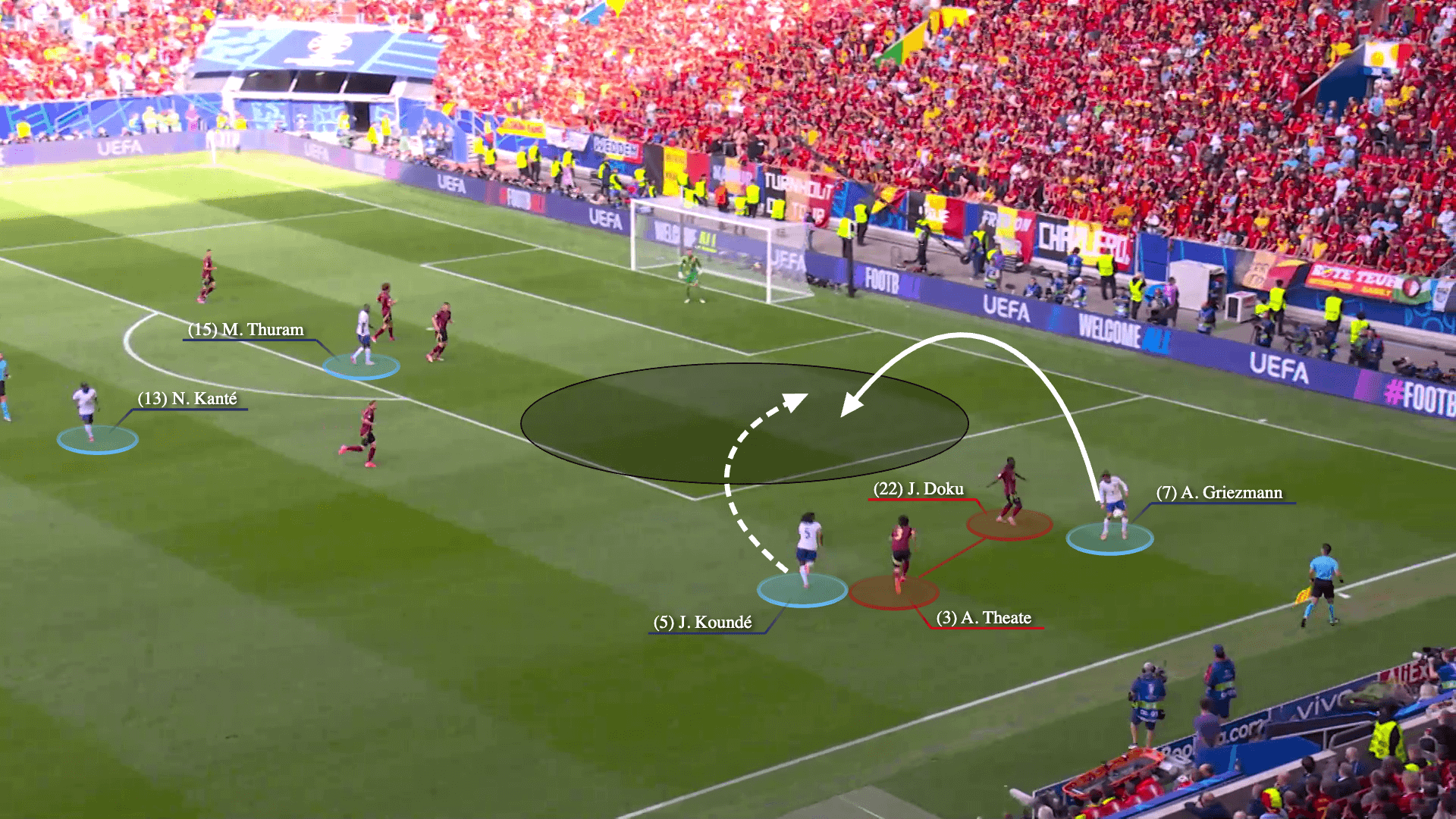

From here, Kounde and Griezmann combine. The latter plays the former in, but nobody joins Thuram in the box — France end up outnumbered six to two (and the two include Kounde, the player doing the crossing), with their main attacking threat Kante staying out on the edge of the penalty area.

Which brings us to point two: when France do get bodies in the box, they are not making very good runs.

This is partly because they did not have to do this at previous tournaments, when they counter-attacked more. Deschamps’ squads have often had pace and dribblers out wide, runners from midfield and a No 9 they can hit in transition.

Advertisement

Only once in 30 games across Deschamps’ five previous tournaments did France fail to register a direct attack (Opta defines these as sequences starting in a team’s own half, with at least 50 per cent forward movement, ending in a shot/touch in the opposition box). Twice in four matches in this tournament, against the Netherlands and Belgium, they have not had any.

Instead, the French are attacking through longer passing sequences; this is partly to control games, though they faced more settled defences. Opponents are more inclined to sit off, given France’s recent major tournament success (to which you can add winning the 2020-21 Nations League) and plenty of these teams having been devastated by their counter-attacks before.

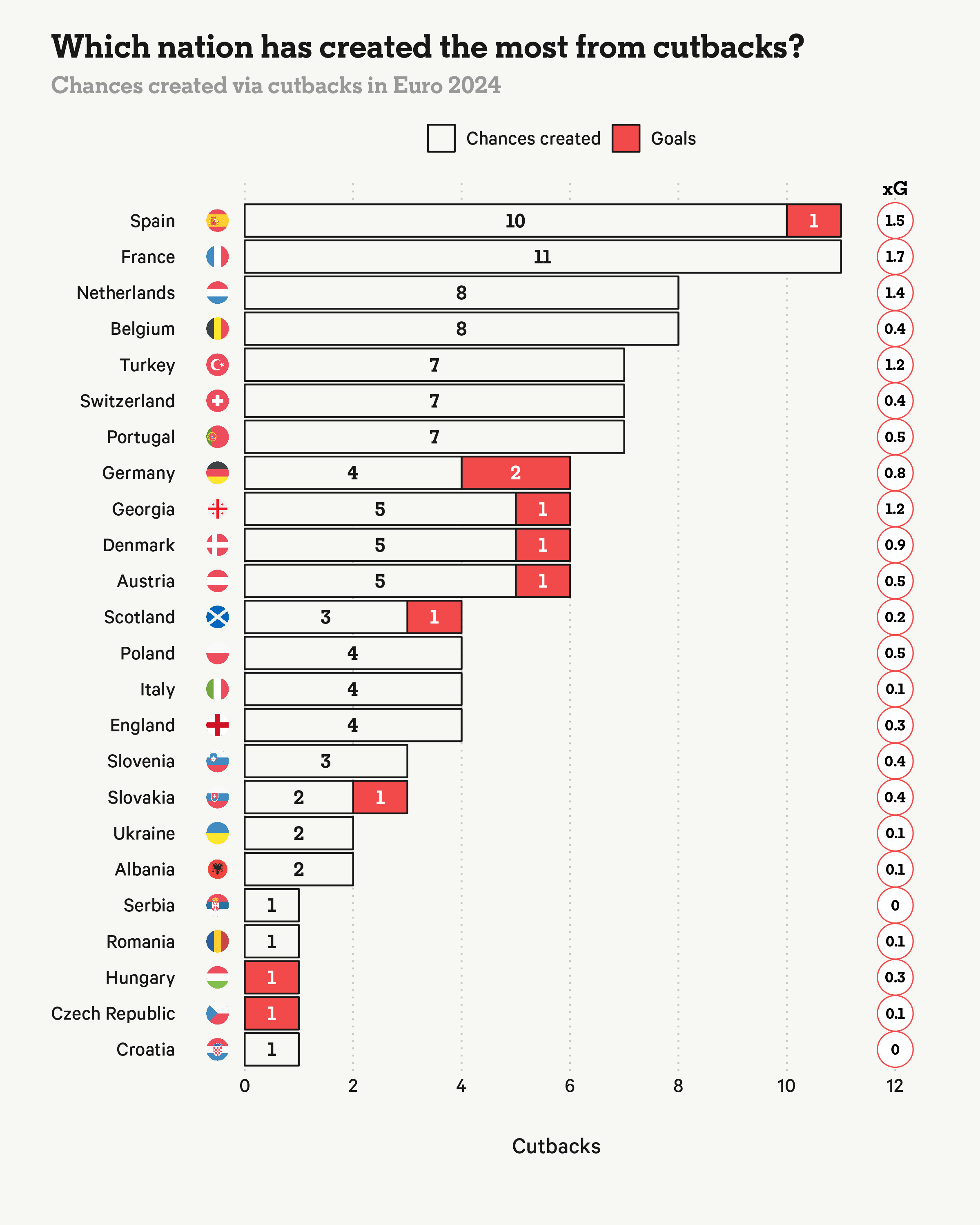

France have already created as many cutback chances in their four Euro 2024 games as in 11 matches at World Cup 2018 (which they won) and Euro 2020 combined. Only Spain can match them at this tournament.

With cutbacks against settled defences, a variety of runs are needed to pull defenders away and give the crosser multiple passing options. Typically, you would want one runner attacking each post (usually the far-side winger will lock off the back post), a player between the six-yard box and penalty spot and a late-arriving No 8.

France have lacked penetrative runs across defenders this summer. Here against Belgium, with another Tchouameni switch to Kounde, they have three in the box (plus Hernandez following in). Nobody runs across a defender. Kounde’s ball to Thuram is pinpoint, but he heads it over the crossbar under pressure.

Here are similar examples, again against Belgium and one in the Netherlands game.

In the latter, France have a three-vs-two in the box, but Rabiot underhits his cross; with Griezmann running backwards, his header is tame. Ideally, that combination would be the other way around (see Rabiot’s header from a Hernandez cross for their first goal of the 2022 World Cup against Australia).

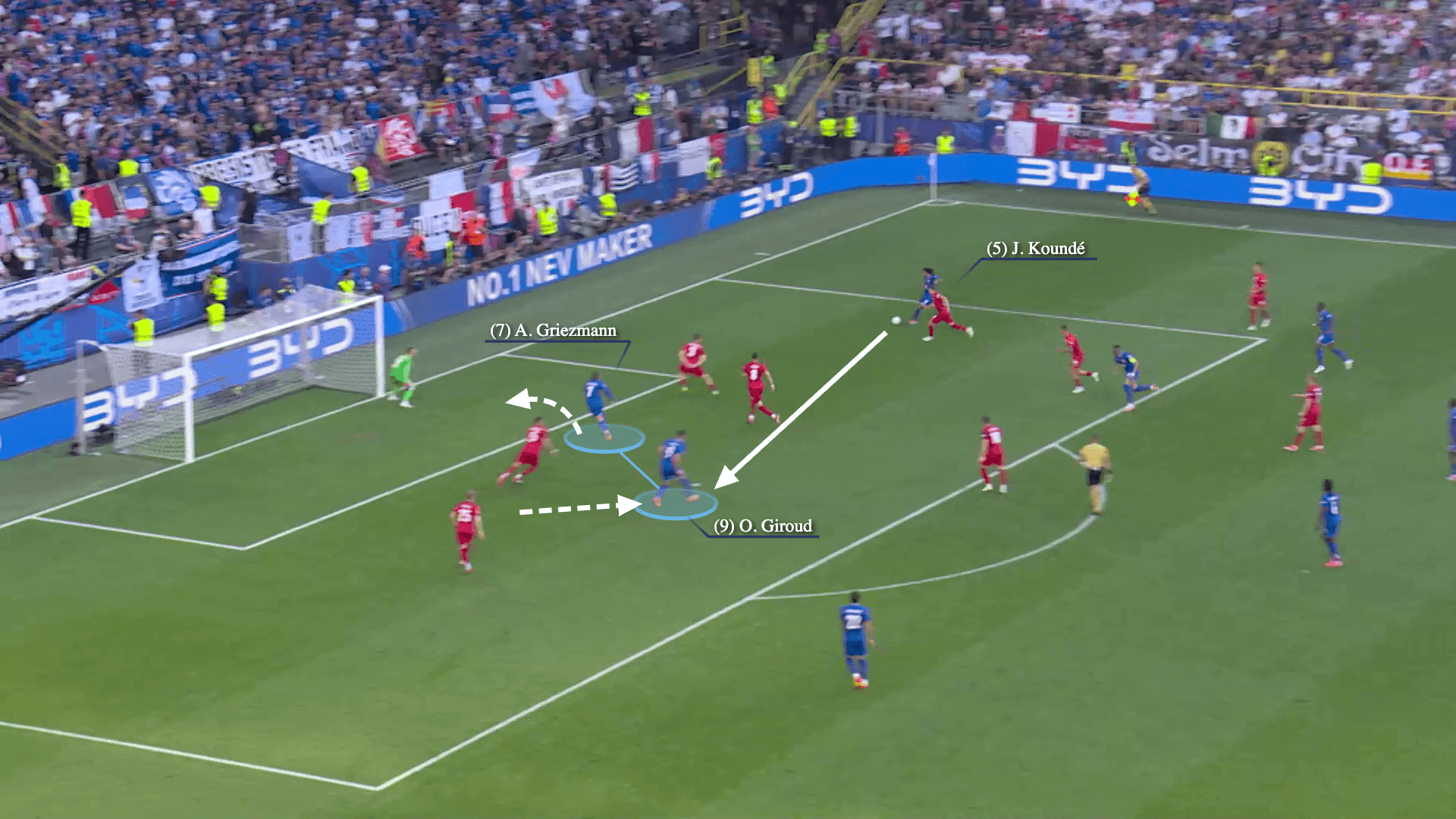

Here is an example of Giroud and Griezmann making different runs well, against Poland. The move ends with Giroud getting a shot off from Kounde’s cutback.

Deschamps has never been tactically dogmatic yet is struggling to find attacking balance.

Mbappe and Griezmann played either side of Thuram in a 4-3-3 against Belgium. In their final group game, the 1-1 draw with Poland, Mbappe was the No 9 with Bradley Barcola to his left and Dembele on his right. That was different from match two against the Dutch, with Dembele still on the right but Rabiot playing off the left and Griezmann as a No 10 behind Thuram.

Advertisement

A balanced forward line is essential when attacking a low block, so the players get used to making the same runs and know the tendencies of their team-mates. France have been practising cutbacks in training sessions between Euros matches, but recreating those moves in pressurised game situations is a different thing entirely.

If they are to keep playing this way, improvements down the left are essential. At times it can become one-dimensional, with Mbappe trying to play hero-ball.

France’s two best cutbacks of the tournament have been from Hernandez getting in behind after a combination with Mbappe. Against Poland, he fizzed a low cross just out of Griezmann’s reach; in the Poland game, a more aggressive run from Dembele across the wing-back would have brought him a tap-in.

There ought to be a greater role for Barcola.

He was one of Deschamps’ wildcard picks for the tournament, having been first capped in the warm-up games in early June. The 21-year-old Lyon academy graduate is very much the heir to Mbappe at Paris Saint-Germain, but he has a wildly different profile. He attacks the back-post incredibly well and is a top-level cutback passer too — see his three assists for Alexandre Lacazette in Lyon’s 5-4 win against Montpellier in May last year.

Here, against Poland, Barcola makes it four France players attacking Dembele’s cutback, which pulls in the opposition’s right wing-back. This makes space for Hernandez to crash the box when the pass goes all the way through — but his shot hits the post.

“The most important thing for me is to adapt to the players and not the other way around. I’m not going to choose a system and put the players into it, I will make sure to choose the system relating to the players I have,” said Deschamps before the 2022 World Cup.

For so long, his tactical flexibility has underpinned France’s success. They have looked a bit different, in terms of personnel, roles and tactics, at every tournament, but kept their strong defensive base.

Advertisement

This time, they have more specific midfield and attacking profiles than before, even if they are bursting with goalscorers — France’s combined goals have risen with every tournament since 2016, from 57 among the players that went to those Euros on home soil to 192 across the Euro 2024 squad.

“The heart of the game in midfield is important, but above all it is attackers who make the difference, who win the matches,” Deschamps also said in 2022.

With a quarter-final against Portugal in Hamburg next on Friday, France must get better at cutbacks or revert to counter-attacking.