JACKSONVILLE, Fla. — Paul Westhead listens intently over the phone as he’s told for the first time that his famed basketball doctrine — the fast-paced, run-and-gun, full-court-press philosophy he refers to simply as “The System” — has propelled a college women’s lacrosse team in northeast Florida to national prominence.

Advertisement

“I’m intrigued,” the 80-year-old coach says with a chuckle.

It’s hard not to be: The coaching duo of Jacksonville University’s women’s lacrosse team, a wife-husband pairing, credits a documentary about Westhead’s methods at Loyola Marymount University as the direct inspiration for their success. They’ve taken The System and tailored it to the lacrosse field, even enlisting one of his most famous former players in their tireless efforts.

More than three decades ago, Westhead arrived at Loyola with his career at a crossroads. He was just five years removed from winning an NBA championship with Magic Johnson, Kareem Abdul-Jabbar and the Lakers. But after that title season, he had been run out of town by Jerry Buss when the Hall of Fame owner decided Pat Riley, an assistant under Westhead, was the best man to lead his franchise into the 1980s.

Westhead was then hired by the pre-Jordan Bulls for the 1982-83 season. He won only 28 games and was fired, his basketball future in doubt.

Still, Westhead believed unwaveringly in his principles. He wanted his team to push in transition on every possession, defend the length of the court from the first whistle to the final buzzer and put up shots within seven seconds of getting the ball. It was an unorthodox way of playing organized basketball, though the style had a defined and illustrious history on the city courts in his hometown of Philadelphia.

He would try it again — both because of his belief and because he knew no other way — at LMU, a small private Jesuit school located less than two miles from Los Angeles’ Playa Del Rey Beach.

After a moderately successful 19-win season in 1985-86, Westhead received reinforcements by way of Hank Gathers and Bo Kimble, two Philly prodigies who had transferred to Loyola from USC after the Trojans basketball program underwent a regime change.

Advertisement

Gathers and Kimble were forced to sit out a year because of NCAA rules, but they finally took the court for the Lions in 1987, and over the next three seasons, The System hit its stride. The two best friends who grew up blocks away from each other in the Rosen projects of North Philly were the engines Westhead needed.

Loyola averaged 110.3 points per game in 1987-88 and 112.5 in 1988-89. They remain the fourth- and second-highest per-game scoring outputs in NCAA history.

The System was an attraction to behold.

In December 1988, the Lions played at Nevada in a regular-season game.

As Westhead tells it, he was standing in line to check in at his Reno hotel when he overheard a conversation between the desk clerk and a customer.

“It’s a little lobby, so I can’t escape the conversation. The guy says, ‘Well, Mr. Jones, what brings you here to Reno?’ He says, ‘I’m going to see the circus tomorrow night.’ And the clerk says, ‘Uh, excuse me, sir, but I don’t think the circus is in town.’ He says, ‘Oh, yes it is. I’m here to see the Loyola Marymount basketball game.’”

The group peaked in 1989-90, averaging an NCAA record 122.4 points per game. Kimble and Gathers, as seniors, combined to average 64.3 points per game.

The Lions appeared destined for a long postseason run before tragedy struck. Seconds after slamming home an emphatic alley-oop dunk during a West Coast Conference tournament game against Portland on Mar. 4, 1990, Gathers collapsed on the court. He died shortly after at a local hospital from hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, a heart-muscle disorder. He was 23 years old.

In the wake of unfathomable grief, LMU, an 11 seed in the NCAA Tournament, made a miracle run to the Elite Eight that included a 149-115 destruction of defending champion Michigan before falling to UNLV in the regional final. In the Lions’ first-round game, a win over New Mexico State in Long Beach, Calif., Kimble shot a free throw left-handed as a tribute to Gathers, who had switched to shooting free throws with his off left hand after years of charity-stripe woes.

“I think about Hank every day, multiple times a day,” Kimble says now, 31 years after Gathers’ death.

That grief has never dissipated. Not for Kimble. Not for Westhead. Not for Loyola. Not for Philadelphia. Not for the basketball community at large.

“He’s not forgotten,” Westhead says, his voice trailing off.

Advertisement

What does this have to do with lacrosse?

That is where our story begins.

The McCords gather the Jacksonville University women’s lacrosse team together for a quick word. (Courtesy of Paul McCord)

The early spring Florida sunshine beat down relentlessly on the artificial turf at D.B. Milne Field. It was approaching midday on Mar. 19, 2013, and the Jacksonville women’s lacrosse team prepared to host Marist. Temperatures hovered in the upper 70s. It felt like 90 degrees on the playing surface. Mindy and Paul McCord, the married couple who founded the Dolphins’ program in 2010 and coach the team, patrolled the sideline.

The game began at noon sharp. Jacksonville jumped out to a 3-0 lead in the first eight minutes of action, flying up and down the field at a pace that, at this juncture, was unheard of in the women’s sport.

It’s what the Dolphins do. They run and run and run some more.

With 10 minutes gone in the first half, the Red Foxes felt the burn in their legs. The heat was oppressive. So was the tempo.

The Marist players turned to their opponents — exasperated, exhausted — and asked, “How are you doing this? How aren’t you tired?”

They got shoulder shrugs in response.

Then, one by one, they displayed their fatigue in the most primal way imaginable.

“They are blowing chunks,” Paul McCord remembers six years later while sitting at his desk in JU’s new Jacksonville Lacrosse Center. “It was one and then another and then another.”

The referees looked around flabbergasted. They had no choice but to halt the game. An official timeout … for widespread puking.

“Hey!” Paul yelled to the refs. “Quit stopping the game!”

The brief reprieve proved futile for Marist. Jacksonville sprinted to a 17-7 victory to improve to 6-3 on the year. The Dolphins finished the regular season 10-5, including a 4-0 mark in conference. They then won three straight tournament games to bring home a conference championship in the Atlantic Sun’s inaugural women’s lacrosse season. That gave JU women’s lacrosse its first NCAA Tournament berth.

Advertisement

Since then, the Dolphins have qualified for four of the past five NCAA tournaments. They’ve gone 56-2 in conference, including their one ASUN game so far in 2019, winning six regular-season titles and five conference titles. That amount of success for such a young program — this is just its 10th season in existence — is unprecedented.

And it all started when Paul McCord, a former Jaguars special teams coach, saw ESPN’s 30 for 30 documentary on three Philadelphia basketball legends — Westhead, Kimble and Gathers — and the system they made famous.

The film, titled “The Guru of Go,” debuted in April 2010 and highlights the Loyola Marymount basketball teams of the late 1980s — the entirety of this harrowing tale, including Westhead’s later success running The System in women’s basketball. He remains the only coach to win a championship in both the NBA and WNBA, which he achieved after claiming a title with Diana Taurasi and the Phoenix Mercury in 2007.

Paul McCord was engrossed by the film. He grew up in Wilmington, Del., just 30 miles from Philadelphia, and played in the same youth basketball league — the Sonny Hill League — as Kimble and Gathers.

Hank Gathers (AP Photos)

Gathers’ death sent shockwaves through the country, but it had a particularly profound impact in Philly. He was Philadelphia’s son, a shining symbol of the city’s rich basketball heritage. And then he was no more.

McCord was a freshman at Delaware when Gathers died. He remembers the moment vividly. So as he watched the documentary, he relived that immense pain of losing a hero.

“It moved an entire generation of athletes like me who watched Bo shoot the left-handed free throw,” McCord said. “I can’t help but get emotional about it.”

It wasn’t until the second or third time he viewed the film that the gears started turning. His sadness turned into inspiration. Maybe, just maybe, he could honor Gathers’ memory down in Jacksonville.

Advertisement

The JU women’s lacrosse team had just wrapped up a disappointing 8-11 debut season in 2010. The Dolphins were overmatched in skill. They struggled in transition and with passing in the attacking zone, and they showed little improvement in the informal fall-ball season.

They needed a spark. They needed something different.

They needed The System.

(Courtesy of Paul McCord)

First, McCord needed to sell his wife on his ambitious vision. She was, after all, the head coach.

The idea started materializing in McCord’s mind when he saw Westhead coaching the Mercury in the 30 for 30. The System worked in women’s basketball. It could work in women’s lacrosse.

“Somehow he’s researching sports and sports history like he always does and he finds this 30 for 30 special and he gets all excited,” Mindy McCord says. “He brings me in, he’s like, ‘You’ve got to watch this!’ And I always have gotten that from him. ‘You’ve got to watch this! You’ve got to watch this!’

“He played basketball, so he totally got it, but I didn’t play basketball. I played field hockey and I ran track. So his ability to be able to say, ‘This basketball game, we can translate (it) into lacrosse.’ I’m watching the special and I’m in tears. … I’m crying. I’m thinking, ‘Oh, it’s such a sad story.’ But he’s like, ‘This is the system we’re going to run.’ I couldn’t see it. I was like, ‘How?’

“He’s like, ‘I know how we can do it.’”

Paul Westhead won a WNBA title with Diana Taurasi and the Phoenix Mercury in 2007. (AP Photo / Paul Connors)

One day in January 2011, Paul McCord picked up the phone and cold-called a man he had never spoken to before.

Bo Kimble.

He relayed his Philly connection. He told Kimble he’d like to play a game in the upcoming season on Gathers’ behalf, a charity event for Kimble’s 44 For Life Foundation, which works to decrease the rate of death and disability due to life-threatening heart conditions. Then McCord detailed his plan: to implement The System in women’s lacrosse, to run harder, faster and longer than any other team, to push the pace and play hounding, pressing defense.

Advertisement

“What’s women’s lacrosse?” Kimble replied.

The conversation progressed, though, and as McCord explained more, Kimble’s excitement grew.

“I wasn’t skeptical at all,” Kimble said. “He started to educate me.”

McCord equated the midfielders in lacrosse to the point guard in basketball. That’s when it clicked for Kimble.

“Instead of having one point guard, you’ve got four,” Kimble says. “So I’m like, OK, well that’s fascinating because all they’re doing is creating pace. That’s going to wear the dickens out of every team. If you have four of those kinds of guys sprinting and just creating pace, that’s going to wear a team out. So I had zero doubt about what they were doing.”

A connection — and what McCord now calls “a really great friendship” — was born.

That March, as JU began its 2011 season, Kimble flew down to Jacksonville to meet and work with the team. His athletic juices kicked in.

“He kind of fell in love with our team and our team kind of fell in love with him,” McCord said. “He started saying, ‘Hey, you should try this, you should try this kind of trap, you should try that kind of trap.’ So he gave us a lot of really good ideas, like inside information of how to do it, and he gave us a little bit of confidence that we needed. He was like, ‘You know the team that shoots the most probably wins the most.’”

McCord during his Super Bowl season with the Baltimore Ravens. (Courtesy of Paul McCord)

Only Paul McCord could convey this level of conviction in an idea most others would laugh at.

But it stems from his upbringing and the way his mind works.

“My entire family is engineers, and I’m the dumb jock,” said McCord, who came up as a football coach, won a Super Bowl with the Ravens in 2000 as their assistant special teams coach and served in the same role for the Jaguars in 2003. “But as a special teams guy, I’ve always thought about how to engineer plays, how to move things around. In football, it’s 11 on 11. Here (in women’s lacrosse), it’s 12 on 12, but it’s a big field. So why is everyone playing this settled, boring game? And I thought, ‘Well, what happens if we put athletes in space and speed everybody up? It’s to our advantage. It’s not to our advantage to play slow.’”

Advertisement

Mindy was coming off a trying 8-11 season in 2010, her first as JU’s head coach.

She took the job when the university asked the McCords to start the women’s and men’s lacrosse programs. The couple had spent the previous decade growing the game in the Southeast through their company, MCC Sports Inc, which Paul had founded after he was let go by Jaguars coach Jack Del Rio after the 2003 NFL season.

Paul had played lacrosse for a week in college at Western Maryland before his football coach yanked him off the field, saying, “You’re our quarterback, you’re out of here, you can’t be out here, you’re going to hurt your shoulder.” Despite his abbreviated lacrosse experience, he dove headfirst into the new company. Mindy had quit her job as the head coach at McDaniel College (formerly Western Maryland) to move to Jacksonville with Paul and their daughter Taylor. Paul had an offer to go coach for the Bills, but Mindy put her foot down. They were staying in Florida.

“He put family first, but he had to sacrifice his career to do that. That’s hard. That’s hard to ask a coach and a male to do that,” Mindy says. “But he had an entrepreneurial spirit.”

Through MCC Sports, Mindy and Paul held camps and clinics throughout the region and eventually were tasked with introducing teams at various high schools. At one point, they were paying 50 coaches’ stipends across the state.

They were the logical choice to establish the first Division I men’s and women’s lacrosse programs in Florida.

(Courtesy of Paul McCord)

Mindy’s first recruit was a girl named Jess Hotchkiss, who had transferred to Jacksonville from Drexel after suffering an injury. Hotchkiss — who now goes by her married name, Vosser — arrived the year before the program was officially founded, when the Dolphins were still just a club team open to all students.

Advertisement

She doubled as Mindy’s recruiting assistant.

“We did 50 tours, her and I on this campus,” Mindy said. “I didn’t have any staff.”

Mindy brought in 21 freshmen girls for the 2010 season. Thirteen of them left after the year.

Even though she now believes in a collaborative culture, Mindy coached with a fierce authoritarian fist that season.

“I have to make this year like hell to weed the kids out that don’t want to build the program,” Mindy recalls thinking. “I was intentionally the hardest I’ve ever been on any program because you have 21 kids, and they’re not all there to build your program. So if you partied, you got cut. I was ruthless. There was no culture. It was the strong survive.”

The struggles of 2010 left Mindy grasping for answers. She asked Paul to join her staff as an unpaid volunteer. Paul didn’t hesitate. And soon after, the lightbulb went off in his head.

“We’ve got to change the philosophy,” Paul told Mindy. “We weeded everyone out, but now we’ve got to make this the best place to play, and we’re going to do this by looking at what we have. We don’t have talent. We don’t have stick skills. But we have athletes. We’re going to create an experience versus a job. We live at the beach, we’re going to practice at the beach. We’re going to do fun things. We’re going to make lacrosse the best part of their day.”

“We switched our thinking,” Mindy said. “I was very open-minded at that point.”

With Mindy on board and Kimble consulting, Paul — who is still technically an unpaid volunteer coach — overhauled the JU women’s program that offseason.

At Loyola, Westhead would spend virtually all of his team’s practice time running transitional drills like three-on-twos and two-on-ones. Kimble imparted this knowledge onto Paul, and the Dolphins started doing the same thing.

In Westhead’s system, the fast break is predicated on very specific court lane assignments. The 1 brings the ball up the floor. The 2 runs to the right corner. The 3 runs to the left corner. The 4 occupies the high left post. The 5 sprints down to the low right block.

JU adopted this almost identically, just applying their lane assignments to more players.

“They’re implementing literally everything that we did at Loyola,” Kimble said.

There are some differences. Jacksonville subs early and often to keep its players fresh, giving time to as many as 25 girls a game. Most women’s teams use between 15 and 16 players, according to McCord. Westhead, meanwhile, barely subbed, keeping his rotation to seven or eight players, maximum.

Advertisement

“Part of it probably was that I didn’t like the dirty looks that I would get from Bo or Hank when they came out of a game,” Westhead says dryly.

Westhead was also renowned and feared for his conditioning tactics. The 30 for 30 spends a segment on the infamous sand dune on an L.A. beach where Loyola players would train for hours in the offseason.

Jacksonville, though, doesn’t condition nearly as much.

“We don’t condition,” Paul says. “Our practice is our conditioning.”

As he developed his own version of The System, Paul also pulled other philosophies from every corner of the coaching world to help it transition onto the lacrosse field.

“Innovators win, and we even innovated The System, how we train it,” Paul said. “Because basketball training and lacrosse training are different because of the field size — number of players, field size, rules. So we went to Anatoly Tarasov and Soviet ice hockey and how did they prepare because they have a lot of mid-ice play.

“So how did they do that? Well, he came up with this thing called the assembly-line method, which is so Soviet, right? The assembly-line coaching method, where as soon as the other team gets the ball, it’s defense. Wherever it is, defense. So his practices were (structured as) either the other team gets the ball and we practice getting it back, or we have the ball and we practice putting it in the net. They didn’t intermingle offense and defense.

“So we started this assembly-line practice to kind of teach our players that there’s no defense — it’s ‘get the ball.’ And there’s no offense — it’s ‘score.’”

When he says “get the ball,” he means it. Paul and Mindy do not refer to their defenders as defense. They refer to them as GTB — get the ball.

“It’s a mindset,” Mindy says.

In the offseason, when they’re training The System, about 10 of their practices are completely assembly-line method sessions. They spend the entire practice playing either offense or defense — the whole team, regardless of position.

Advertisement

“Even if you’re an offensive player, you’re an attacker, you have a whole day where, unless you intercept the ball in the zone, you’re not shooting the ball at all,” McCord said. “You’re playing defense the whole practice. And there’s days where the defense plays offense the whole practice.”

Many of these principles have developed over the past decade. But the process began in that offseason after 2010.

The question was, would it actually translate?

JU opened its 2011 season with a home game against Cincinnati. Paul and Mindy were apprehensive on the sideline. They had lost to the Bearcats by six goals the previous year.

“I have no idea if this is going to work,” Paul remembers thinking. “No idea.”

Hotchkiss had similar doubts. “She looks at me and she goes, ‘Is this really going to work?’” Mindy said.

In the second half, though, they all witnessed the tell-tale sign of The System at work.

“You could see the Cincinnati players starting to lean down on their shirts a little bit,” Paul says, “and you could see our players be like, ‘She’s done.’”

The Dolphins bested Cincinnati 18-10. Two weeks later, they hosted Denver, a top-25 team, and pulled out a 10-7 victory.

“We’re all looking at each other like, ‘We have no business beating Denver,’” Mindy says. “Their stick skills were superior to us. But our guys were so bought in to the concept.”

Hotchkiss jumped into Mindy’s arms and knocked her over.

“‘You were right! You were right!’” Mindy remembers Hotchkiss yelling over and over. “I’m thinking, ‘You guys had to actually perform. You had to do it. We were just rolling the dice.’”

Mindy and Paul with Jess Hotchkiss following her graduation from JU. (Courtesy of Paul McCord)

At the time, it was the defining win of JU’s young lacrosse life. It catapulted the program to new heights. It instilled confidence in the team. These ladies believed in The System. As Kimble puts it, they “drank the Kool-Aid.”

How could they not?

They finished that season 14-5 and led the nation in scoring at 16.21 goals per game. They went 15-4 in 2012 and 13-6 in 2013, when they reached their first NCAA tournament. In their first nine seasons, the Dolphins led the nation in scoring five times, including four straight seasons from 2011-14. Last season, they averaged 18.45 goals per game, their most ever. This year, they averaged 17 goals per game en route to an 8-2 start to the season.

Advertisement

The System hasn’t led to NCAA tournament success … yet. The Dolphins have lost in the opening round in each of their five appearances. Maybe it’s a flaw in The System. Maybe they just need more time.

“It takes 10 years to be an overnight success, and here we are,” Paul says. “If you run The System, it might be a little faster.”

All the while, Paul has kept innovating. In the summer of 2012, he pored over 10 years of NCAA data to pinpoint significant statistics. It was “the Moneyball theory” of women’s lacrosse, Mindy says, alluding to the baseball ideology of identifying undervalued stats.

Since then, Jacksonville has focused on two primary numbers related to shooting and possessions. Paul won’t reveal his secrets other than to say, “One is a very basic one that everybody keeps track of, and one is an internal metric that we have.”

Then he’s back into Soviet hockey.

“The way that the Soviets thought about goal production was: five players score goals, one player shoots the puck,” he says. “And that’s kind of like our seven-on-seven game. Seven players score the goal, one player shoots the ball.”

Westhead, after hearing the specifics of Jacksonville’s strategy, starts to tell of his own experiences with lacrosse.

His 13-year-old grandson Luke plays on a high-level club lacrosse team in California, so he has some familiarity with the game. He also went to a different grandchild’s high school — St. Margaret’s Episcopal School in Orange County — to teach a clinic to lacrosse players on pick and rolls in transition offense, also known as drags, at his son’s request.

Westhead imparts these facts so he can be fully forthright about the extent of his limited lacrosse knowledge.

But when he’s told the story about the Marist girls puking all over the field — “the Chunky Game,” as Paul McCord calls it — the connection becomes a little clearer.

“Yeah,” Westhead said. “Well, I have multiple stories about that for you.”

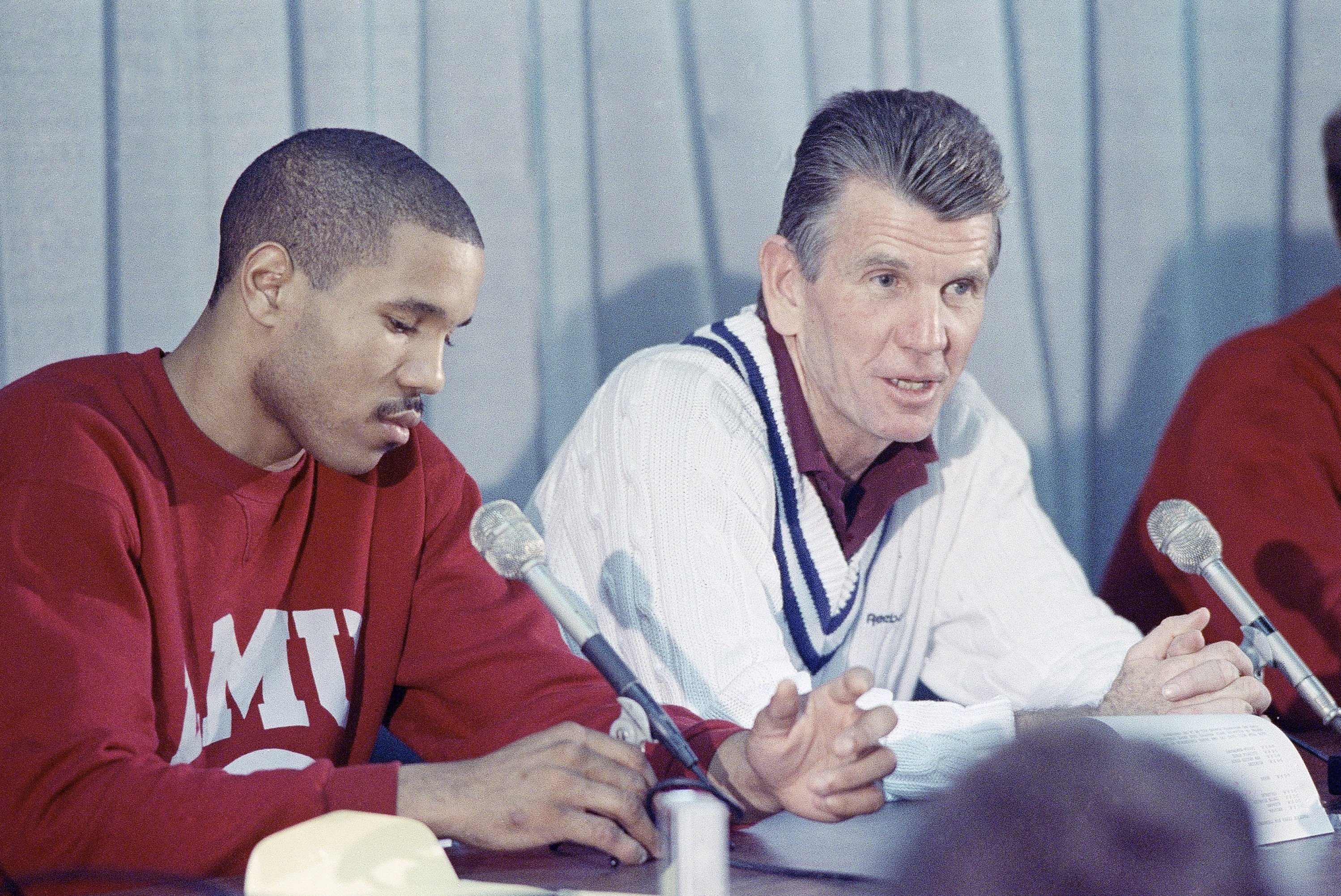

Loyola Marymount’s Bo Kimble and coach Paul Westhead during a news conference on Mar. 15, 1990 following the death of Hank Gathers. (AP Photo / Alan Greth)

The System breeds these kinds of tales.

“While I was at LMU, we were playing Holy Cross, they came out to play during Christmas break,” Westhead continues. “We were right on top of our game, we were playing fast, and Holy Cross played pretty good. With about five minutes to go, it was like 110-95. They were still around. It wasn’t a blowout. And then everything kind of ended the way it looked (127-104). So I saw the coach (George Blaney) after the game, and I said, ‘Hey, you guys played good. Good job.’ And he said, ‘They were done with 14 minutes to go in the game.’ I said, ‘No, no, George, no, your guys played well! They did a good job. They were there with four minutes to go in the game. They were still alive and running.’ He said, ‘No, no, Paul. I don’t mean my players. I mean the officials.’

Advertisement

“He said at the 14-minute mark, they stopped, and one stood at one end, one stood in the middle and the other one stood at the other end. He said they never moved for the rest of the game. They were physically done.”

The bond is undeniable. The stories are the glue.

“There was always evidence, every game,” Kimble says.

It’s opponents doubled over, hands on knees or holding the basket stanchion for support. It’s their own players thriving off the visible exhaustion of their foes. It’s officials halting games or being unable to move. It’s the unrelenting pace.

“It makes me think maybe I would have had a better career as a lacrosse coach, not basketball,” Westhead says. “As exciting as it sounds, you know I had 20 jobs, so I got fired a lot of times, too. Maybe I would have been a permanent fixture as a lacrosse coach.”

Kimble cheers on the Jacksonville women’s lacrosse team. (Courtesy of Paul McCord)

Kimble is truly the link. He makes two to three trips to Jacksonville every year to watch games and speak to the team.

“I just enjoy letting them know that, ‘Hey, look, you guys are going to put a lot of work in, they’re going to train you and give you all the tools to be successful, and you’re going to run more than you’ve ever run in your life,’” Kimble says. “But let me be crystal clear, I just want them to know that what they’re doing and the style of play and everything they’re teaching, if you don’t believe anything else, just don’t believe that it doesn’t work. Because it does.”

This year, Paul and Mindy arranged for the team to take a visit to Loyola Marymount’s campus. They toured the basketball facility at Gersten Pavilion, where Gathers’ and Kimble’s numbers hang in the rafters. In the back corner of the gym is a big banner with the No. 44 on it encompassed by a white circle. Underneath, in bold lettering, it says “HANK’S HOUSE.”

Kimble flew out to take the tour with the team, but he was hospitalized with pneumonia before he got the chance. Every Jacksonville player, along with Paul and Mindy, went to see Kimble in the hospital. They had to go in groups of three because of hospital rules.

Advertisement

“I love the program. I love being there for them,” said Kimble, who is back to full health and hopes to one day coach at a Division I basketball program. “I was happy to see everybody.”

The Loyola basketball team gave Paul and Mindy a room so they could watch the 30 for 30 with their squad. They show the film to their players at least twice a year. They want the players to grasp how close Gathers and Kimble were, how close the whole team was, how they were a family fused together by love and devotion and sacrifice to a singular cause.

“There’s a brotherhood that’s there that we had at Loyola Marymount,” Kimble says, “and the 30 for 30 tape allows you to see how close our team was and how much we really loved Hank.”

“One thing led to another,” Westhead said of that team. “We assembled a group of players that were not only talented but hungry. … They all wanted to show that they could really play. I was doling out this speed game that they had never seen before, and they bought into it. And once they got it, it was like a pride thing. It was something that they knew that they could do against anybody. So I think it kind of formed a bond because of the style of play. They knew they were special, and therefore they became closer together.”

(Courtesy of Paul McCord)

Paul and Mindy want their players to understand that the style of play is more than just goals, assists and turnovers forced.

They are keeping Hank’s memory alive.

“It hits home when our kids watch the special,” Paul says. “I think everybody feels that emotional bond and connection.”

“There’s so much power behind other people’s stories, and we’ve taken a story to help create our own legacy,” Mindy says. “And we show that as a reminder of what our purpose is and what we have to stay focused on.”

In the 30 for 30, filmmaker Bill Couturié splices in readings from Westhead’s personal journal.

One of them was written after Hank died.

“Perhaps the truth is The System could only happen once in a lifetime,” Westhead recites, “and it ended with Hank’s fast-break dunk.”

Paul, however, tries to find a positive out of the tragedy.

“Maybe it began at that dunk,” he says. “For us.”