The moment some parents have been anxiously awaiting for months is almost here: The Pfizer-BioNTech Covid-19 vaccine for children aged 5 to 11 will likely be authorized for use in the next week, after completion of a four-step process that begins today.

It is also a moment some portion of parents has been dreading for months. And over the weekend, they made their concerns known to experts on the Food and Drug Administration’s vaccines advisory committee, which meets today to review the evidence on the Pfizer vaccine’s safety and efficacy in kids ages 5 to 11. Members of the the Vaccines and Related Biological Products Advisory Committee (VRBPAC) were deluged by an organized email campaign urging them not to recommend the vaccine.

“Over the weekend I was getting about one email every minute,” said VRBPAC member Paul Offit, a vaccines expert at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, who said by the time the weekend was over he had received “hundreds and hundreds.”

Offit and colleagues on VRBPAC will meet all day to review the data and are scheduled to vote at the end of the day on whether, in their estimation, the benefits of the vaccine outweigh the risks for this group of children. If authorized, the Pfizer vaccine will be the first pediatric Covid vaccine.

The FDA is not bound to follow VRBPAC’s advice, though it often does, and disregarding it on an issue as sensitive as authorizing a Covid vaccine for children would make for a problematic launch of the program to vaccinate 5- to 11-year-olds. While the committee’s vote may not be unanimous, it is unlikely to vote against authorizing this vaccine for children.

A day or so after VRBPAC votes, the FDA is expected to issue an emergency use authorization for the Pfizer vaccine. Step three of this process is having advisers to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention review the vaccine’s safety and efficacy and vote on whether CDC Director Rochelle Walensky should recommend its use. The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices meets next Tuesday, Nov. 2. If it advises Walensky to recommend the vaccine, the CDC director is likely to do that within hours, allowing the vaccination of 5- to 11-year-olds to begin as early as Nov. 3. There are already 16 million doses of the pediatric vaccine available — with more to come — for states to order and they have been ordering it, though shipping won’t begin until the FDA issues the authorization.

Matthew Herper and I will be live-blogging today’s VRBPAC meeting, which begins at 8:30 a.m. ET. You can watch it here. We will be posting our updates and analysis below in reverse chronological order; check back often.

— Helen Branswell

Just one last thing

Seriously, this is it.

Michael Kurilla, the only person who abstained on the vote, issued a statement explaining his rationale. There were multiple factors that effectively boil down to the fact that he doesn’t think all children need this vaccine — many have already had Covid infections and have some immunity because of it — and he’s not convinced the vaccine’s protection will last long enough given the current schedule of two doses administered three weeks apart.

Some children clearly need this vaccine, said Kurilla, director of the division of clinical innovation at the National Institutes of Health’s National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, but “I don’t see the need for ‘emergency use’ of this vaccine across the entire age group and would have preferred a more nuanced approach.”

— Helen Branswell

VRBPAC postscript

6:45 p.m.: When VRBPAC meetings get to the point where members are discussing the question they have to vote on, it can be really hard to stop listening long enough to write an update for the blog. So I wanted to circle back to a couple of things now that the meeting is over.

The first: A question from Michael Kurilla, director of the division of clinical innovation at the National Institutes of Health’s National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, elicited an interesting answer from Pfizer.

Kurilla asked whether the company is generating any data on different dose schedules for its vaccine, suggesting the 21-day interval currently used produces a “sub-optimal” response, at least in terms of the durability of the immunity induced.

William Gruber, Pfizer’s senior vice president for vaccine clinical research and development, appeared to acknowledge the dosing schedule may need work. But he said when the vaccine was being developed and tested, the pandemic was raging and the goal was to protect people as quickly as possible.

“Obviously as we think farther ahead to a post-pandemic period, and particularly as we get into very younger populations, it may be advisable … particularly in that first year of life, to look at longer intervals as part of a routine immunization series,” Gruber said. “But we don’t have that data now.”

The second: The dynamic of these meetings is really interesting and can be a bit deceiving at times. For example, at a point this afternoon it looked like several members of VRBPAC might vote against the motion, effectively telling the FDA they didn’t think the vaccine should be authorized for children 5 to 11.

In the end, that didn’t happen. No one voted against the motion, though Kurilla abstained. (We’re still waiting to hear why.) This isn’t the first time I’ve seen this happen. In fact, it’s not uncommon.

A number of reporters asked Paul Offit, the vaccine expert from Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, about this VRBPAC tendency after the meeting concluded. Offit chuckled and said, “We do that.”

“We express all our concerns, just get it out there. That makes everyone feel better and then we vote the way we should have voted right from the beginning,” he said.

Making these decisions is not easy, Offit noted. “The fact of the matter is you’re basing a decision for millions of children on a study of 2,400, really,” he said of today’s vote. “And that’s uncomfortable. So you want caveats. But you don’t get ’em. As [chair] Dr. Monto said over and over again, it’s a binary decision.”

That’s all she wrote.

— Helen Branswell

The abstainer

4:25 p.m.: Michael Kurilla, director of the division of clinical innovation at the National Institutes of Health’s National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, was the VRBPAC member who abstained.

— Helen Branswell

The vote

4:16 p.m.: The panel voted on the following question:

Based on the totality of scientific evidence available, do the benefits of the Pfizer- BioNTech Covid-19 vaccine when administered as a 2-dose series (10 micrograms each dose, 3 weeks apart) outweigh its risks for use in children 5-11 years of age?

Yes: 17

No: 0

Abstain: 1

— Matthew Herper

The panel pushes, FDA and CDC push back

4:08 p.m.: Panel chair Arnold Monto has now tried to get the FDA to change the wording of the question twice — and has been rebuffed by the FDA’s Peter Marks both times.

Several panelists clearly worry that while they believe the vaccine should be an option, particularly for kids who are at risk, they’re not sure the data exist for a wide approval. “Help us out in terms of what happens if we vote yes,” Monto said, “and clearly if we vote no the vaccine will not be available to anyone.”

Marks once again said that he’d like to stick with the question as worded.

Amanda Cohn, a CDC representative on the panel, chimed in to say that she thought the panel’s discussion reflected the difficulty of balancing risks and benefits in children. But she said that she believed that, as worded, the benefits of the vaccine clearly outweigh the risks and that the measures for detecting rare side effects will allow the U.S. to change course if myocarditis is more problematic than it appears.

“To me, the question is pretty clear: We don’t want children to be dying of Covid, even if it is far fewer children than adults and we don’t want them in the ICU,” Cohn said.

That may not be enough to assuage all the panelists’ concerns. Earlier in the discussion, James Hildreth, CEO of Meharry Medical College, said, “This is a really tough one. I do believe children at highest risk do need to be vaccinated, but vaccinating all the children to achieve that seems a bit much to me.”

And Michael Kurilla, an NIH researcher, called it “ the toughest decision” and said he resented the “binary presentation” of the question. But the panel may decide to clear the vaccine, and leave restrictions on the vaccine to the CDC’s ACIP committee.

A VRBPAC vote is coming soon.

— Matthew Herper

Some of the committee members have concerns

3:40 p.m.: Committee members are now discussing the question they’re supposed to vote on: “Based on the totality of scientific evidence available, do the benefits of the Pfizer- BioNTech Covid-19 vaccine when administered as a 2-dose series (10 micrograms each dose, 3 weeks apart) outweigh its risks for use in children 5-11 years of age?”

The answer is binary, as chair Arnold Monto has informed the group more than once. They are to vote yes or no.

It’s clear some people on the committee think the vaccine should be available, but maybe isn’t something all children in this age group need.

Cody Meissner, at pediatrician at Tufts Medical Center, raised concerns that if the vaccine is authorized for this age group, school mandates will follow. Meissner said he opposes them.

Ofer Levy, director of Harvard Medical School’s Precision Vaccines Program, asked if the wording of the question could be changed to give the committee some leeway.

Peter Marks, FDA’s director of the Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research, is clearly trying to land this plane on the runway the FDA designated. He has asked the committee to vote on the question as written and see what happens after that.

— Helen Branswell

The public has thoughts!

2:15 p.m.: The public comment section — a full hour! — just ended. Seventeen people weighed in with their thoughts about authorizing the Pfizer vaccine for kids 5 to 11 years old.

There isn’t much middle ground here. People either really want their kids to be have a chance to be vaccinated against Covid, or they really don’t.

During these sessions, which are a feature of every VRBPAC meeting, speakers are drawn by lottery, if more people want to address the committee than will fit into the designated time. Today the lottery favored people who strenuously object to using this vaccine in this age group. (And others.)

One of the things that became clear through their presentations is that people who don’t want to vaccinate their children are afraid that an emergency use authorization for Pfizer’s pediatric vaccine will be quickly followed by vaccine mandates, with Covid vaccines added to the list of immunizations children need to attend school.

“Your approval today means mandates tomorrow,” Josh Guetzkow, a senior lecturer in law at Hebrew University of Jerusalem, told the committee.

— Helen Branswell

Nobody said balancing risk and benefit was simple

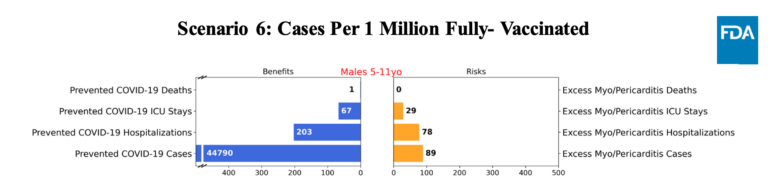

12:45 p.m.: The FDA’s Hong Yang presented the agency’s analysis of the balance between risks and benefits for the vaccine among kids ages 5 to 11.The FDA has already said it views the benefit of the vaccine as outweighing the risk.

What’s interesting, though, and helpful about these models is they show how different variables, such as how much Covid is spreading, the risk of myocarditis from vaccination, and the efficacy of the vaccine, make a big difference in the risk-benefit calculus. And these are all things we don’t know. Included here are the models on males, because myocarditis occurs mostly in males.

At current rates of infection, the benefits outweigh the risks. If the infection rate drops as low as it has ever been, it’s a closer call. But the models also use a rate of myocarditis for older kids. It probably won’t be as common in younger kids. And if you believe that, once again, the picture changes. See all three charts below.

First, a model with high rates of Covid-19.

This is what happens Covid-19 infections decline.

And finally, here’s a model with a lower risk of myocarditis.

These are scenarios the panelists have to decide on. Do they think the rate of Covid will be higher or lower than expected? And do they think the risk of myocarditis will be higher or lower? The models are useful not so much because they tell the panel what to do, but because it focuses the topics for debate.

Another point: the FDA and experts on this panel have argued that hospitalizations for myocarditis following vaccination are less serious than those caused by Covid-19. So making those kinds of judgements will be part of the discussion, too.

— Matthew Herper

Myocarditis always occurs more often in males

12:38 p.m.: One obvious question: why are myocarditis cases occurring in boys, not girls? The CDC’s Matthew Oster included this graph in his presentation. This is for myocarditis at different ages. As you can see, the difference is pretty profound.

— Matthew Herper

How will the panel think about myocarditis?

11:12 a.m.: The panel’s goal today is going to be to balance the benefits of vaccinating kids, which are fairly clear, with the risks. The main risk is a condition called myocarditis, an inflammation of the heart, and the panel just got a lot of sometimes preliminary data about it.

First, here’s what’s clear: There is an increased risk of myocarditis associated with the second doses of both the Pfizer/BioNTech and Moderna vaccines, both of which use a new technology called mRNA. In those ages 12 to 15, 39.9 cases per million were reported to the Vaccine Adverse Events Reporting System after dose two of the Pfizer vaccine. In those ages 16 or 17, 69 cases per million have been reported. In those ages 18 to 24, the rate is 36.8 per million per million for the Pfizer/BioNTech vaccine and 38.5 per million for the Moderna vaccine. Those are all higher than the background rate of the condition.

A presentation by Matthew Oster, a CDC researcher and a cardiologist at Sibley Heart Center in Atlanta, showed exactly how complicated things get beyond that.

How do these young people with myocarditis do? Of 1,640 reports sent to the CDC, 877 met a CDC definition of myocarditis. (Another 637 are under review.) Eight hundred and twenty-nine were hospitalized, and 789 of those were discharged. Nineteen were still hospitalized, with five in the intensive care unit. The status of the others wasn’t know.

Myocarditis, Oster emphasized, is not a single condition. It is normally caused by infection, but can also stem from other causes, like autoimmune disease or medication. Traditional myocarditis seems somewhat different than what is caused by the vaccines. Covid-19 infection also causes myocarditis, both as a result of acute infection and as a result of multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C). Oster presented data from two health systems that seemed to indicate that MIS-C myocarditis is more common than myocarditis that is simply caused by Covid.

Oster also provided some background on what is traditionally known about myocarditis. It is normally more common in males in their late teens, and rates decline steeply as they age through their 30s and 40s. (The hypothesis, he says, is that testosterone levels play a role.) That seems to mirror what is being seen with the vaccines, and it might indicate that risk will be smaller for 5- to 11-year-olds than it is for teens.

Children with vaccine-associated myocarditis seem to mostly have characteristics that predict they’ll recover smoothly, including hearts that are still pumping normal amounts of blood. But they do have some results on magnetic resonance imaging that could indicate long-term effects, Oster said. Those are being followed.

There’s not a lot of controversy that the vaccine is causing some myocarditis. The question for the panelists is going to be how to weigh this against preventing Covid-19, which may cause more of the condition, and how severe these cases are. Later this morning, the FDA will present its own risk-benefit analysis, which concluded that the benefits of the vaccine are greater than its potential risks.

— Matthew Herper

Making the case to vaccinate

10:25 a.m.: The formal part of the meeting begins with two presentations from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention on the toll Covid-19 is taking on kids, particularly those in the age group today’s discussions focus on. The first — which I’m focusing on here — looked at the epidemiology of Covid in kids 5 to 11 years old. Matt’s following the second, on myocarditis following vaccination.

Fiona Havers, a medical officer with CDC’s Covid epidemiology task force, described a disease impact that is at least as significant on kids as is the annual flu epidemic — or at least the flu epidemics in the pre-Covid era. (Flu activity has been at historic lows since March of 2020.)

There have been at least 1.9 million Covid infections among all children, Havers said, noting that because many children have asymptomatic infections or very mild symptoms, that number is likely to be an underestimate. Kids 5 to 11 have recently begun to make up a bigger portion of all Covid infections; in the week ending Oct. 10, they made up 10.6% of the nation’s Covid cases.

Covid hospitalizations among children in this age group are about on a par with those reported in some recent flu seasons, Havers said, though not the 2019-2020 season that preceded the pandemic; it was a long and intense flu season. There have been 8,300 pediatric Covid hospitalizations to date, with rates three times higher among Black, American Indian, Alaska Native, and Hispanic children as for white children.

While deaths among children hospitalized for Covid were similar to deaths among children hospitalized for flu — 0.6% — other outcome measures suggest Covid hospitalizations among kids involved somewhat more severe disease, she said. For instance, they were more likely to require intensive care and to need mechanical ventilation.

In the period from Jan. 1, 2020, to Oct. 16, 2021, 94 children aged 5 to 11 died from Covid in the United States, Havers said. And more than 5,200 children have been diagnosed with Covid-related multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children or MIS-C, a difficult condition that can occur in some children after an infection.

Children do experience long Covid, but at lower rates than adults, Havers said. A survey in the United Kingdom found that between 7% and 8% of children report continuing symptoms 12 weeks or longer after infection.

She also noted that illness isn’t the only toll Covid is taking on kids. They are losing school time, with more than 2,000 unplanned school closures so far this school year affecting more than 1 million children.

— Helen Branswell

The opening salvo

9:11 a.m.: Peter Marks, who heads the FDA’s Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research, gave brief opening remarks. It’s hard not to take them as an early argument that the panel should favor approval.

“Far from being spared from the harm of Covid-19 in the 5-to-11-year-old age range, there have been over 1.9 million infections, over 8,300 hospitalizations, about a third which required intensive care units stays, and over 2,500 cases of multisystem inflammatory disorder from Covid-19,” Marks said. “And there have also been close to 100 deaths, making it one of the top 10 causes of death in this age range during this time. In addition, infections have caused many school closures and disrupted the education and socialization of children.”

In a reference to the torrent of email received by some of the panelists over the weekend, Marks said that there were “strong feelings that have clearly been expressed by members of the public” both for and against the use of the Pfizer/BioNTech vaccine.

He also emphasized that other agencies, not the FDA, will make decisions about whether the use of vaccines will be mandated, and that this topic should not be part of the panel’s discussion.

— Matthew Herper

Some context for today’s discussions

7 a.m.: The Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine is the only one of the U.S.-deployed Covid vaccines that can be used by people down to the age of 12. Anyone 12 and older gets the same dose of vaccine, on the same regimen — two 30 microgram shots given 21 days apart.

But for younger children, the FDA required the company to conduct additional tests to determine the safety and efficacy of the vaccine in children. Pfizer tested three doses: 10 micrograms, 20 micrograms and 30 micrograms. It is seeking emergency authorization for the 10-microgram dose, which is one-third as much vaccine as is given to adults. The company said Friday that the children’s dose was 91% effective at preventing symptomatic Covid-19 in this age group.

Side effects were generally similar to those reported by adults who got the Pfizer vaccine — things like headaches and fevers.

One of the hallmarks of an FDA review is that the agency doesn’t just take the word of a would-be manufacturer of a vaccine or drug; its staff reanalyze the original data to ensure the FDA agrees with the claims the company seeking a license or emergency authorization is making.

Matt reviewed the FDA’s analysis, which was released Friday night. The agency’s scientists concluded the protection offered by the vaccine would definitely outweigh any risk of myocarditis — inflammation of heart muscle — that the vaccine appears to trigger rarely in some teens and young adults, mostly males. The cases seen after use of the vaccine appear to be milder than regular myocarditis and of shorter duration. At least in teens and young adults, Covid infection is far more likely to trigger myocarditis than the vaccine is, according to research from Israel.

The Pfizer study compared 1,518 children who received the vaccine to 750 children who received a placebo. There were three cases of symptomatic Covid among the former and 16 among the latter. The vaccinated children who contracted Covid had very mild symptoms; none had fever. But 10 of the 16 unvaccinated children had fevers and symptoms were more pronounced overall in the placebo group.

The FDA analysts used mathematical modeling to estimate how many hospitalizations would be prevented by vaccinating a million boys in the 5 to 11 age range at six different points in the pandemic in the United States. At most points, the vaccine would prevent 200 to 250 hospitalizations per one million vaccinated boys. But when transmission of the SARS-CoV-2 virus was low, as it was in June 2021 — before the spread of the Delta variant — the vaccine would only have prevented only 21 hospitalizations per one million boys, the agency’s model suggested.

That meant, the FDA said, that at times of low transmission the vaccine might trigger slightly more myocarditis-related hospitalizations in boys than Covid-related hospitalizations it prevents. But even then, it said, the benefits may still outweigh the risks, because the myocarditis cases are mainly mild and the Covid cases that require hospitalization are more severe.

The need to balance the vaccine’s benefits versus the risks of myocarditis is likely to be the key issue of today’s discussions. At least one VRBPAC member, Tufts Medical Center pediatrician Cody Meissner, has been indicating for months that he has serious concerns about using the vaccine in people who are at lower risk of developing severe disease if they contract Covid. Kids definitely fall into that category, so Meissner will likely be vocal today.

— Helen Branswell

To submit a correction request, please visit our Contact Us page.

STAT encourages you to share your voice. We welcome your commentary, criticism, and expertise on our subscriber-only platform, STAT+ Connect