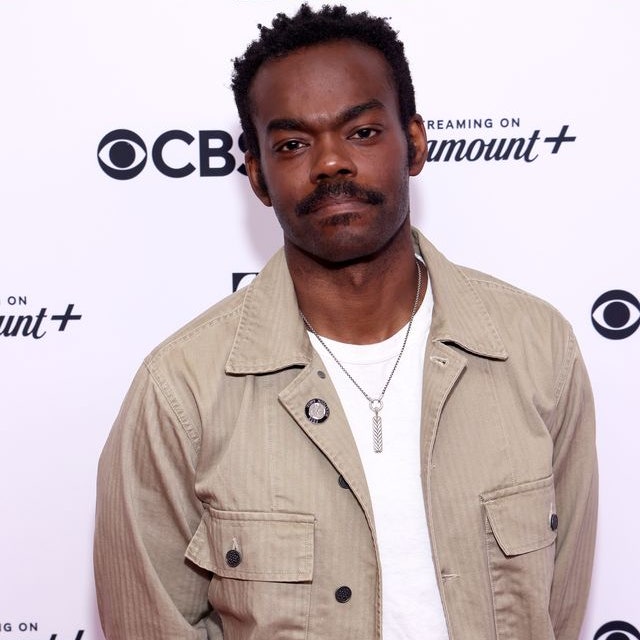

Few have the kind of year onstage that William Jackson Harper is still in the midst of. About a year ago, he returned to New York theater for the first time in six years to play the lead role in Primary Trust, a bookstore employee who faces an uncertain future after getting laid off. Eboni Booth’s off-Broadway premiere won the Pulitzer Prize in drama, with Harper winning the Obie Award for distinguished performance and receiving a Drama Desk Award nomination for lead performance. The next spring, he made his way back to Broadway for Heidi Schreck’s savvy adaptation of Chekhov’s Uncle Vanya. As the lovelorn, occasionally drunken Dr. Astrov, Harper immediately stole the show—so much that he was nominated for the best-actor Tony (his first) over the guy playing the titular role (that is, Steve Carell).

The Dallas-born actor is still performing Vanya every night, with the production’s run set to conclude in a few weeks. A few hours before Friday’s show, Harper joined me on Little Gold Men (read or listen below) to reflect on his whirlwind past 12 months. Most came to know Harper through his breakout turn as Chidi on NBC’s acclaimed sitcom The Good Place. Before he nabbed that role, he was a workhorse on the Manhattan theater circuit, often completing more than one show a year; once Good Place got going, his screen career blossomed in projects ranging from Barry Jenkins’s The Underground Railroad to the terrific second season of Love Life, and he took a break from the stage. Now he’s back, better than ever, and ready to chart a new course.

Vanity Fair: You’re in the midst of Uncle Vanya’s run right now. We’re recording on a Friday, so what does a typical Friday look like these days?

William Jackson Harper: I get up, go to the gym, eat some breakfast, walk my dog. Tend to take it easy in the afternoon. Usually around, I want to say like 3 or 4, I start to try to power down and not have anything going on. Usually no interviews, but right now, especially since the Tony nomination, there’s been a lot more press and stuff in the afternoon and some events in the afternoon right up until I go into the theater.

I usually go into the theater about an hour and a half before showtime, just to warm up and do my little rituals and all that stuff, and get ready to do the show. It’s a long-ish commute from my place to the theater. The evening is pretty much shot starting around 4:30 or 5:30, and then everything is wrapped out by around 11:30 or so. So it winds up being an eight-hour day on the back end of the day. It seems weird because it’s only a two and a half hour show, but it just takes a lot of focus to get in the right headspace to be open and available onstage.

I’m wondering how that applies to playing drunk—because you are quite good at it in this play! How do you approach that night by night?

Well, honestly, that’s something that took a minute to dial in. Even after opening, I was still figuring it out. Because one of the things that I wanted to do was for the drunkenness to feel a little bit out of control, which is something that I notice in people when they’re drunk, especially friends of mine. Maybe the words aren’t slurring, maybe they are stumbling a bit, maybe they’re not—but there’s something where it feels like this conversation or this encounter could go off the rails at any moment because people are not filtering themselves. I wanted to have that element be present, but at the same time, I wanted to make sure that I’m really connecting with my scene partners onstage and not let it be purely about the physicality and the manifestation of being drunk.

I’m relying on the text and the word-vomit that Astrov has in that moment in the play, to inform what drunkenness is for him. The filter’s off. There’s a little bit more emotional vulnerability. Things are just at the surface a little bit. And also: I am having fun. This is a party for me. I want everyone to have a good time. So that allows for some of the flirtation and some of the jokes and things to come out without it being forced. I’m trying not to have it be forced, and I want to make sure that I’m connecting. I was playing a lot with physicality, and perhaps earlier on in the run connecting less with my partner—and now it’s more trying to center it on my partner and letting some of that other stuff come when it comes. It just takes some time, some calibration.

What was your relationship to Chekhov coming into the play? You’ve said that you never conceived of doing Chekhov professionally until fairly recently.

Yeah, no, I didn’t. Something about the path not taken, and regret, and having a lot of your basic needs met so therefore you can sit and think about the other stuff that’s been bugging you—that you put to the side when there’s more pressing issues. Getting older, having a little more stability—which I feel really privileged to have—has allowed me to perhaps understand some of these characters a little bit better. Also when I was younger, the only translations that I had read were in English, but they felt very British and culturally a little distant for me. It was hard for me to penetrate in a lot of ways.

Heidi’s translation knocks down a lot of those barriers to entry, and it becomes about: What is it to be a middle-aged guy who’s not sure if he’s made the right choices with his life and is finding himself empty after thinking that he’s found his purpose and being like, “Oh, well, maybe I haven’t, what am I doing?” That’s something that as I’ve gotten older, I’ve felt at times, and I needed some time and some age to actually understand that feeling. When I was younger, I had a little bit of a fever that I needed to sweat out.

I’m really interested in that personal connection. You’ve called Kenneth, whom you portrayed in Primary Trust, one of the closest characters to yourself that you’d ever played. How does that change the equation as an actor?

The thing that’s really interesting about it is, when a character feels very close, it allows for me to make choices that come straight from my gut. They may not make any sense narratively, but they make some kind of emotional sense, maybe. There’s a freedom in being able to just try stuff that’s coming from a personal place as opposed to intellectually trying to understand what this person’s gone through and how that manifests.

I don’t want to question it too much because that feels human to me, that you would have certain reactions that may not make complete narrative sense. But they make a kind of emotional sense. I’m more open to those impulses. Whereas when it’s something that’s farther from me, I have to do a different kind of homework to put myself in a place where I can just explore. When it’s close to me, I can just start from there.

It feels related to one of your main draws as a stage actor, which is that you bring a real everydayness.

That’s something I try to do. Earlier in my career, I wanted to make sure that everyone knew that I was making good choices, and now I’m a little less concerned with that. I’m a little bit more invested in whomever I’m playing feeling like someone you could meet…. I’ve seen performances where people can make these very external choices and come from the outside in and they can live in them very fully. It’s a little bit harder for me at this point. I need to start with where I’m at and see where the character sits in me, and then work from that place. That hopefully lends itself to feeling more like a real person rather than someone who’s showing you how good a job they’re doing, which is something that I think I probably did earlier on.

From what I understand, you were doing a ton of theater until The Good Place came along. A screen career blossoms from there—and with these two plays, it’s the first time you’ve done stage work since you got that show.

Yeah. Yeah.

So how did it feel broadly, just coming back to theater in a very different position as an actor—even just economically speaking?

Well, economics is sadly one of the biggest things. One of the things that led me to trying to make sure that I showed people I was doing a good job—that, “I’m valuable, I’m worth it”—was because I needed something from the job other than the pleasure of doing the job. I needed the play to lead to something else. And since The Good Place, I don’t need the play to lead to anything else. I need the play for the process and for what it gives me, which is it sharpens my tools in my toolkit a little bit.

When I was just doing plays, the career stuff was very much in the back of my mind while I was working. I was seeing people do plays like what I was doing and then get a really great job after that. That just wasn’t happening for me for a very long time. I just had to put plays away for a little while and focus on trying to get that stability. And now I can come back and just enjoy the process and actually be there and explore the character without feeling like, “This has got to do something, this has got to change things.” The desperation is out of the window.

I feel like this might set a high bar though, right?

I mean, kind of, but recognition is great. [Laughs] Earlier in my career I wanted stuff like this so badly, because I thought that this was going to open up opportunities for me. And I’ve been really fortunate in that a lot of opportunities have opened up before this recognition came in. So it’s nice, but also I will still do plays just because I’m interested in the play. Whether that leads to something else or any recognition down the road, it’s not all that important to me. I just love getting to do good work with people that I like.

Do you think about how you want to balance screen and stage going forward, with that new mentality?

If it was up to me, I’d probably do a play every year. There’s a process that you get in theater that you just don’t get when you’re working on camera. I’m sure that maybe movies are different—I haven’t worked on those kinds of movies or haven’t had those kinds of parts of movies where you do an extensive rehearsal—but on TV, you memorize your lines and you’re doing these little snippets and there’s so much happening around you. The rehearsal is really more about where you need to be for the camera. You might get some time to talk with your scene partners about what’s happening in the scene and what’s going on, maybe with the director, maybe with the showrunner. But there’s a lot of people that have a lot to get done and we’re trying to make the day.

I like being able to do theater just because it does broaden the range of choices that I find my brain tapping into. I’ve been in this place where the name of the game is: You go in, you try something and it’ll probably not work, but you tried it. You chased it down as far as you could go, and then you discard it if it just doesn’t do anything. But there’s little nuances here and there that maybe you get to retain, and maybe you get to use as you move forward. When I’m just doing TV, I find that I’m sometimes trying to make sure that I am just getting the scene and that we’re making the day. That’s always going on in the back of my head a little bit, and I need to be able to let go of that a little bit.

What are your Tony night plans?

Well, we have a show that day. So I’m going to finish the matinee, maybe get my haircut just because it’s wild under here right now. And I don’t know, we’re going to go to the Tonys. I hear to bring snacks because it’s a long night, and then afterwards I want to see what the parties are all like. But honestly, I’m looking forward to just snuggling up with my partner at the end of the day and taking stock of it all. With us being in production and with the Tony nomination coming out, I’m really just focused on making sure that we maintain the integrity of the play and that I am present and really there for that. I’ve kind of pushed some of this other stuff out of my head. Once Tony night happens, it’s going to be a couple of drinks, and I’m going to come home and pet the dog and hang out with my lady.

This interview has been edited and condensed.

More Great Stories From Vanity Fair

RFK Jr.’s Family Doesn’t Want Him to Run. Even They May Not Know His Darkest Secrets.

In the Hamptons, Wealthy Biden Donors Fear a “Dark” Future Under Trump

An Epic First Look at Gladiator II

Palace Insiders on the Monarchy’s Difficult Year

Donald Trump’s Pants-Pissingly Terrifying Plans for a Second Term

I Taught the Taylor Swift Class at Harvard. Here’s My Thesis

The Best Movies of 2024, So Far

Score New VF Merch With the Fourth of July Deal at the VF Shop