San Twin begged her mother to stay home.

It was March 2020, and COVID-19 was spreading inside the slaughterhouse where Tin Aye worked in Greeley, Colorado.

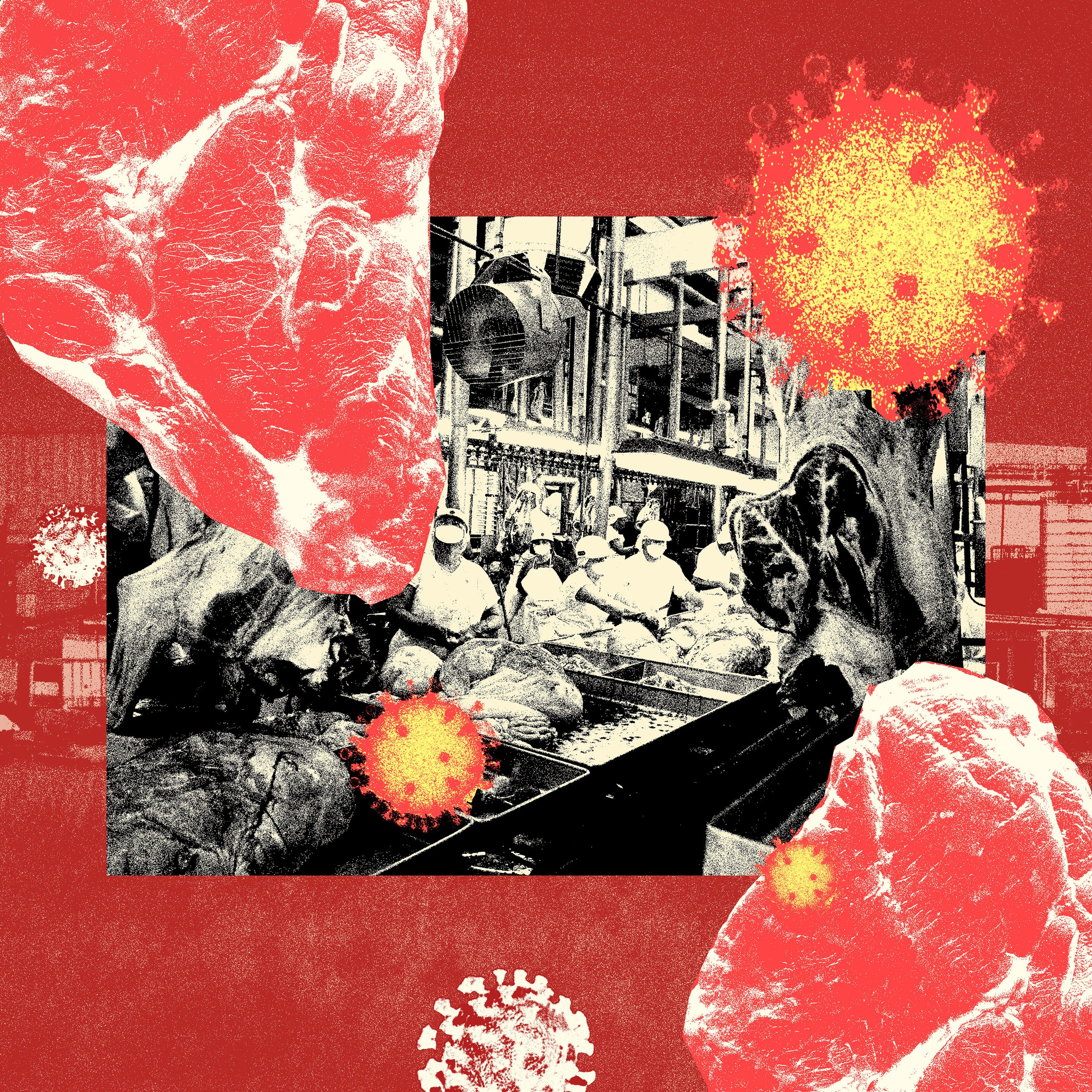

San Twin did not understand the contours of the danger, or how this lethal virus spread. But it seemed safe to assume that it was being accelerated by the very conditions in which Aye labored. Inside the vast, dank slaughterhouse, as many as 1,500 people per shift carved cattle into cuts of beef, processing more than 1 million animals per year. They stood for hours on an assembly line in close proximity to one another, amid spraying water jets and sanitizing chemicals misting down from the ceilings. Some wielded knives and saws to hack away at sides of beef, sending blood spurting. Others scooped away innards and excrement.

Aye’s job was plucking finished cuts of meat from the assembly line, packaging them in plastic, and putting them in boxes. She and her coworkers sweated and breathed heavily as they attended to their duties, straining from exertion. Some wore face masks they brought to work themselves, but this tended to fog up safety glasses, so many went without. A man who stood just behind Aye on the plant floor had already contracted COVID-19. Workers nervously speculated about who would be next.

The slaughterhouse was owned by JBS Foods, a Brazilian conglomerate, and the largest meat processing company on earth. Through a series of mergers, it had captured control of one-fourth of the American capacity to turn cattle into steaks and hamburgers.

The two brothers who oversaw JBS, Wesley and Joesley Batista, carried a reputation for hard-charging business practices that verged into criminality. Back in Brazil, an explosive scandal had revealed how they had bribed three presidential administrations and a key official at the Brazilian Development Bank in a scheme that secured nearly $5 billion for their international expansion spree. Much of the cash for their American incursion had come via that endeavor. Both brothers had spent about six months in prison in Brazil. By the time the pandemic arrived, they had been out for two years, their meat empire intact, with a collective fortune worth more than $5 billion.

Their business was perfectly positioned to exploit the panic of the pandemic, as families stuck at home compensated for the shut-down of schools and restaurants with home-cooked meals and heftier portions. But cashing in required that workers like Tin Aye continued to show up at slaughterhouses.

As fear among the workers in Greeley mounted, JBS remained tight-lipped about how many people inside the plant had contracted the coronavirus. By the end of the month, more than eight hundred plant workers were refusing to turn up for shifts, fearful of bringing COVID-19 home to their families. Workers at other slaughterhouses across the country were staying home, too.

San Twin was tormented by the thought that her sixty-year-old mother was spending every workday inside a COVID-19 hotspot. A member of the Karen people, an oppressed ethnic minority in Myanmar, Aye had survived a harrowing escape from her homeland while pregnant with her only child. Together, they had sustained themselves for fifteen years in a refugee camp inside Thailand, living in a bamboo hut without electricity or plumbing. They had subsisted on rice and beans donated by the United Nations, supplemented by whatever cash Aye could earn cleaning houses, doing laundry, and tending pigs.

They were eventually offered a choice of countries in which to settle, among them Canada, Australia, and Norway. They picked the United States, having heard that this was a place where a hard-working immigrant could always find a job. They landed in Denver in the summer of 2012, knowing no one and speaking no English. Aye got a job working nights at the slaughterhouse in Greeley, an hour’s drive north. She carpooled with other Karen immigrants, leaving for the plant in the early afternoon and returning at four in the morning.

The work was grueling and relentless. Aye came home with an aching back, swollen fingers, and bruises on her legs. She also returned soaked—not only because of the misting chemicals and spray jets, but because bathroom breaks were so infrequent that she sometimes urinated in her clothes.

She started at $12 an hour, which seemed like a lot of money.

As the pandemic emerged, San Twin’s fear of losing her mother was compounded by the fact that she was pregnant.

“My mother was the only family that I had,” Twin told me as we sat on the floor of her home in Denver in December 2021. She was nearly thirty, and about to open her own restaurant.

Her son Felix, then twenty months old, sat quietly in her lap, gazing at the older woman in the framed photo on the living room wall. Aye wore glasses and was draped in a white lace shawl, her steely resolve giving way to a warm smile. Here was the grandmother that Felix would never meet.

“I said, ‘Please don’t work in the plant anymore,’” Twin told me. “She said, ‘I have to pay the bills. I’m strong. I’ll be okay.’”

Aye was among the nearly three hundred workers at the Greeley slaughterhouse who tested positive for COVID-19 during the first several months of the pandemic, and one of at least five people who died. And the Greeley plant was merely one facility within an enormous industry consumed by the virus. Across the United States, 59,000 meatpacking workers contracted COVID-19 over the course of 2020, with 269 people dying.

That so many ordinary workers found themselves in harm’s way in the midst of a pandemic was no mere misfortune. It was a direct outgrowth of the business plans pursued by their corporate bosses. The largest agribusiness conglomerates had placed the imperatives of their shareholders above the welfare of their employees.

Worse, they manufactured fears of a meat shortage to gain the complicity of the American government. They fomented public alarm over potential disruption to the food supply as a way to justify the ultimate sacrifice of their workers—all in the service of boosting their profits.

On April 18, 2020, a doctor at a hospital in the Texas panhandle emailed JBS to warn the company that its slaughterhouse in the nearby town of Cactus was the source of an intensifying wave of COVID-19.

“One hundred percent of all COVID-19 patients we have in the hospital are either direct employees or family members of your employees,” the doctor wrote. “We believe there is a major outbreak of COVID-19 infection in your Cactus facility.” He added: “Your employees will get sick and may die if this factory continues to be open.”

But the plant remained in operation. Ten days later, President Trump intervened to ensure that it would stay that way. He cited the Defense Production Act—a law dating back to the Korean War—in signing an executive order barring the shutdown of meatpacking plants as a threat to national security. “Such closures threaten the continued functioning of the national meat and poultry supply chain, undermining critical infrastructure during the national emergency,” Trump’s order declared. “Given the high volume of meat and poultry processed by many facilities, any unnecessary closures can quickly have a large effect on the food supply chain.”

In essence, Aye had to continue risking her life, or Americans would risk going hungry.

This formulation from the Trump administration constituted a decisive victory for the meat industry. It validated a propaganda assault aimed at stoking fear of food shortages as the means of maintaining business as usual, echoing talking points crafted by officials at the North American Meat Institute, the grandly named advocacy shop for the industry. This was not a coincidence. Top agribusiness executives had been meeting and corresponding regularly with senior Trump administration officials to plot strategy engineered to keep slaughterhouses open.

The most critical element to this partnership between the White House and the meat industry was their dissemination of the false theory that closing slaughterhouses jeopardized the nation’s access to food. This was a point that key industry executives had been voicing loudly to ratchet up anxiety.

Two weeks before Trump’s executive order, the president and chief executive officer of the meat conglomerate Smithfield Foods, Ken Sullivan, raised the specter of empty grocery store shelves as he announced the closure of a pork processing plant in South Dakota.

Such disruptions were “pushing our country perilously close to the edge in terms of our meat supply,” Sullivan said in a press release. “It is impossible to keep our grocery stores stocked if our plants are not running.”

Yet at the same moment that Smithfield issued those frightening words, American meatpackers were collectively sitting on 622 million pounds of frozen pork—far more than they held before the pandemic. The largest meatpackers in the United States had enough inventory to stock the shelves of every grocery store in the land. They were in control of an enterprise so vast that they were increasingly selling their products to households on the other side of the world. Over the course of 2020, Smithfield and JBS both dramatically expanded their exports of pork to China. Their supposed concern for the sanctity of the American food supply did not preclude them from sending home-raised meat across the Pacific.

The JBS plant where Tin Aye worked was one of the nine largest meatpacking plants in the country. Typically, it exported nearly one-third of its output to twenty different countries. The notion that she had risked her life to feed the nation was both tragic and ludicrous.

Smithfield’s warning of meat shortages was such a brazen lie that it prompted ridicule even within the National Meat Institute.

“Smithfield has whipped everyone into a frenzy,” wrote the head of communications at the trade association, Sarah Little, in an internal email. She added that Sullivan, the CEO, was “directing the panic,” even as he was focused on promoting exports.

“So basically the meat shortage story is that there is no shortage,” wrote another member of the trade association staff.

But the most important audience for the tale of vanishing grocery stocks, the Trump White House, not only bought the deception but acted on it.

In the middle of March 2020—just as San Twin was imploring her mother to stay home—representatives for major meatpacking companies began meeting with senior officials at the US Department of Agriculture, seeking action that would compel slaughterhouse employees to continue showing up.

Trump’s Department of Agriculture escalated the warnings of a threat to the food supply, passing them on to Vice President Mike Pence. The campaign produced a recommendation from the Department of Homeland Security that states should classify slaughterhouse workers as “critical infrastructure.” That designation was aimed at ensuring that workers would continue turning up for shifts even in communities where local quarantine rules and other social distancing measures called for them to stay home.

At the same time, executives for the largest meatpackers, including JBS, personally beseeched Trump’s secretary of agriculture, Sonny Perdue, for help in persuading slaughterhouse workers that showing up for their shifts was their best option. They specifically discussed how to convey to workers that they would not qualify for government benefits if they missed work.

On April 3, 2020, the executives held a call with Perdue to ask that he press the White House to involve Pence or Trump in their undertaking. In a subsequent email, they thanked Perdue for his time and urged him to orchestrate “a strong and consistent message from the President or Vice President” that “being afraid of COVID-19 is not a reason to quit your job and you are not eligible for unemployment compensation if you do.”

Four days later, Vice President Pence gratified the industry during a Coronavirus Task Force briefing at the White House. He expressed concern over “incidents of worker absenteeism” at some slaughterhouses, which had led to “some plants having reduced capacity.” He urged slaughterhouse workers to keep the assembly lines moving.

“Thank you for what you’re doing to keep those grocery store shelves stocked,” Pence said. “You are vital. You are giving a great service to the people of the United States of America. And we need you to continue as part of what we call our critical infrastructure to show up and do your job.”

By the time Pence delivered those words, Tin Aye was in the intensive care unit at a Denver hospital.

She had labored for weeks through severe coughing and a high fever while her daughter had implored her to go to the hospital. Only when she was struggling to breathe had she finally sought medical attention, setting aside her reluctance to spend the money for care.

That same week, San Twin was in another hospital, having delivered Felix via an emergency caesarean section after she suffered painful contractions and shortness of breath. A test revealed that she, too, had COVID-19.

The day after Felix was born, Aye called from her own hospital bed to deliver the news that, according to her doctors, her COVID-19 was extremely advanced.

“She was calling to say goodbye,” Twin told me. “She said, ‘I really want to see you, but I can’t see you anymore.’ She told me to work hard for Felix. Just believe in the positive view and help yourself and others. And then she dropped the phone, and I never talked to her again.”

Aye suffered two strokes and slipped into a coma. She was kept alive by a ventilator until she drew her final breath on May 17, 2020.

As I spoke with Twin more than a year later, she could not shake the sense that her mother had been used and discarded by a rapacious industry. Her gut-level sentiment took affirmation from the astonishing profitability of the enterprise in which Aye had labored. During the first two years of the pandemic, the four largest American meatpackers showered shareholders with more than $3 billion in dividends. The year that Aye died, JBS celebrated revenues of $22 billion on sales of beef in the United States. “The results for 2020 make us very proud,” the CEO of JBS, Gilberto Tomazoni, told investors.

The company gave Twin $6,000 to help with her mother’s funeral arrangements and never called to offer condolences, Twin told me.

The Department of Labor’s Occupational Safety and Health Administration later cited JBS Foods for “failing to protect employees from exposure to the coronavirus.” The federal body levied a fine of $15,615. That was less than what JBS earned on its sales of beef in the United States every thirty seconds.

“They did not care about human beings,” Twin said. “They only care about the money.”

Excerpted from the book HOW THE WORLD RAN OUT OF EVERYTHING: Inside the Global Supply Chain by Peter S. Goodman. Copyright © 2024 by Peter S. Goodman. From Mariner Books, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers. Reprinted by permission.

More Great Stories From Vanity Fair

Peter Thiel, J.D. Vance, and the Dangerous Dance of the New Right

Ivanka Trump, Sensing Power, Slinks Back to the National Stage

An Epic First Look at Gladiator II

Looking for Love in the Hamptons? Buy a Ticket for the Luxury Bus.

The Dark Origins of the True-Crime Frenzy at CrimeCon

Palace Insiders on the Monarchy’s Difficult Year

The Best TV Shows of 2024, So Far

Listen Now: VF’s Still Watching Podcast Dissects House of the Dragon