9

Landscape of Policy, Funding, and Planning

This chapter discusses the following:

- Nested scales of government involved with community-driven relocation and the interrelationship of funding, policy, and planning within this framework

- Federal agencies, programs, and policies that dictate or provide funding for elements of community-driven relocation, split by disaster-related agencies, agencies not primarily disaster-related, and nonfinancial technical assistance

- State buyout program examples across the United States

- The lack of and need for regional planning for community-driven relocation within the Gulf states, with examples of state planning entities in each state that could address such issues

- Local-level buyout program examples from across the United States and land-use planning for relocation

- Private and public-private funding and programs related to community-driven relocation

INTRODUCTION

The present chapter takes a closer look at the current landscape of laws, government agencies and programs, and state and community resilience and hazard mitigation plans (HMPs) that can or do play a role in facilitating (or hindering) relocation when the status quo is untenable and relocation is deemed necessary (whether as a result of discrete disasters or gradual changes). The chapter reviews this landscape at the federal, state, regional, and local levels of government, as well as nongovernmental institutions that work alongside government entities. Each section examines how agency- or program-specific mechanisms for funding shape what is actually possible in terms of relocation. The chapter describes the complex web of programs, policies, funding opportunities, and plans that communities pursuing relocation must navigate in the absence of a formal federal program focused on community-driven relocation. The ramifications of this complexity will be discussed in Chapter 10, including issues of equity, social vulnerability, and justice.

As this chapter shows, the several government entities that work in this space have different areas of focus. For example, the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) is largely focused on response, hazard mitigation, and disaster recovery, while the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE)—with some degree of involvement from FEMA and the Natural Resource Conservation Service of the U.S. Department of Agriculture—is focused on floodplain management. Meanwhile, the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), the other major federal agency discussed below, is focused on housing and community infrastructure. These differences at the federal level can result in competing or contradictory goals and approaches. For example, in Fair Bluff, North Carolina, the U.S. Department of Commerce’s Economic Development Administration invested in a business center while, in the same area, FEMA-funded buyouts of houses and businesses were undertaken (Flavelle & Belleme, 2021). Another example of multiple sources of funding supporting multiple courses of action is Princeville, North Carolina, where FEMA and HUD are funding buyouts, USACE is planning a new levee (Flavelle & Belleme, 2021), and the town is in the process of moving part of its community to a 52-acre site located outside the floodplain (Smith & Nguyen, 2021). Despite the existence of many laws and programs that could support community relocation, the existing legal framework does not address relocation in a coordinated, comprehensive manner that communities can easily navigate (FEMA, 2023g; Howe et al., 2021; Ristroph, 2019). In some cases, as discussed below, local and state programs can complement federal programs, especially when states and local communities are given greater flexibility in how they administer federal programs and are given the time to plan for this complex activity. (Newtok,

Alaska, is representative of this type of effort [Ristroph, 2021]; see Chapter 3 of this report for more.) However, this is not the norm and at times there are disconnects among federal and other governments, as well as between local government leadership and community members (see Box 9-1).

Legal and funding structures can be disaster-related, a reactive approach, or non-disaster-related, to include a proactive approach that involves acting based on sound planning practices. Government programs, and the agencies that run them, most commonly follow a disaster-recovery model when facilitating relocation and other courses of action around environmental threats such as increasingly destructive hurricanes, subsidence, and sea level rise. In a disaster-recovery model, much of the available funding comes episodically as a reaction to a specific disaster or in the form of annual nationally competitive programs. Furthermore, it may not be aligned with state and community policies and plans, particularly those relating to capital improvements. This stands in contrast to a model of proactive measures, where funding might be available year-round and allocated based on risk and need.

These two models of action are not the only difference in the approaches of various government agencies, programs, and plans; the intended purpose of the funding can also vary. Resilience approaches—which encompass a range of measures that a community can take that aim to prevent, plan for, mitigate against, react to, and recover from disasters—will continue to be important as these communities navigate the evolving threats of climate change. As shown below, that approach is much more common than relocation.

Furthermore, the notion of community relocation itself is highly varied (as discussed in more detail in Chapters 1 and 3). This is due to several factors, including a deep attachment to place, the lack of a coordinated governmental strategy within and across jurisdictions and agencies, and the narrowly defined grant programs available. In most cases, relocation is undertaken by local governments, and involves a partial movement of housing and a community’s physical assets. Communities typically draw from multiple sources of post-disaster recovery funding, including grants tied to the removal of hazard-prone housing alongside funding to repair and rebuild other parts of a community. In one of the largest known examples in the United States, in the 1990s, thousands of homes in multiple Midwest communities were purchased, demolished, and relocated following floods (see Chapter 3). In most cases, less flood-prone parts of the communities remained, often protected by large levee systems.

Finally, disaster aid (financial or otherwise) is a critical factor in recovery and resilience, but the type of aid can be more important than the amount (Greer & Trainor, 2021). For example, one study found that

temporary housing can slow permanent household recovery (Peacock et al., 1987, cited by Greer & Trainor, 2021). In order for aid to be effective, agencies need to align the timing of aid programs with the community’s capacity to accept and manage the program(s), and ensure programs meet household needs and are designed to efficiently and effectively address these needs (Greer & Trainor, 2021). In addition, Zurich (2013) stressed the need to rebuild structures to be more flood resilient and suggested that governments and insurers can play a role in this by creating incentives and providing advice. Other effective drivers of action include economic incentives and regulatory and market drivers (Dawson et al., 2011; Suykens et al., 2019; Valois, Tessier et al., 2020; Zou et al., 2020).

Below, the focus is on federal, state, and regional levels of government. However, it is important to note that in many cases, there is insufficient attention placed on supporting local capacity building, drawing from local bases of knowledge and experience (see Chapter 7), and addressing relocation-specific challenges, such as the programming of the resulting open space, the identification of receiving areas, and the construction of replacement housing and new communities (see Chapter 8). Each of these deficiencies benefit from inclusive, collaborative planning, as the committee also discusses in Chapter 8.

BOX 9-1

Disconnects Among Federal and Other Governments

At a committee seminar for Mississippi and Alabama, Derrick Evans, executive director, Turkey Creek Community Initiatives in Gulfport, Mississippi, spoke of bottlenecks or dead ends in the system of funding that is supposed to flow between different levels of government:

“We have produced numerous federally funded, place-based, intelligent, actionable, fundable […] community plans […] that would benefit the entire city […] But we can’t prevent elected leadership […] from (a) not participating on the front end, (b) being surprised that all of a sudden there’s this federal windfall [of funding], (c) thinking it is meant for them […] almost like private new development capital, or (d) don’t move forward with that 8 million dollar coastal Restoration Grant. […] Local government leadership can be a dead end, or the last stop, or the last point in a funnel that lets the resources through.”

SOURCE: Derrick Evans, Executive Director, Turkey Creek Community Initiatives in Gulfport, Mississippi, and Gulf Coast Fund for Community Renewal and Ecological Health (2005–2013). Virtual Focused Discussion: Mississippi and Alabama Gulf Coast Community Stakeholder Perspectives on Managed Retreat, March 2023.

Nested Scales for Regional Planning

As was introduced above, multiple government levels come into play when a community considers or pursues relocation. Understanding the different levels of institutions and how they connect is important to understand which agencies have the ability to invest in or otherwise contribute to solutions. The FEMA Hazard Mitigation Grant Program (HMGP) buyout approach, as illustrated in a report from the Natural Resources Defense Council (see Figure 9-1) and described in more detail in the next section, offers an example of nested scales of decision making (Weber & Moore, 2019). The HMGP buyout process involves a multifaceted collaboration among federal, state, and local entities and homeowners that spans approximately five years. Initiated by a presidential disaster declaration, FEMA invites affected states and tribes to apply for funding, which is further broken down into local “subapplications.” Local entities, in preparation, identify potential participants, conduct analyses, and collate necessary documentation. However, they often grapple with uncertainties around funding amounts and requirements for matching funds, leading to delays. Once FEMA approves applications and disburses funds, local jurisdictions manage property-related activities like appraisals, offers to homeowners, and demolitions. Although FEMA allows a year-long application window postdisaster, the ensuing procedures displayed in Figure 9-1—from property appraisal to demolition—are intricate (Weber & Moore, 2019). Because of this intricate web of procedures and people across multiple levels, a lack of coordination and leadership at the federal level trickles down, placing additional pressures on state, regional, and local entities to manage the coordination of resources.

Interrelationship of Funding, Policy, and Planning

In addition to the nested scales described above, this chapter discusses three interrelated elements of relocation: funding, policy, and planning. Funding is the money available to fund relocation and planning for relocation. Policies dictate how much funding is available, for whom, and for what activities. Planning defines more specifically what actions will take place with available funding within a state or locale, adhering to policy and funding stipulations. Additionally, federal policies may require that plans (e.g., HMPs) exist at the state or local level in order for a state or locale to receive funding, and funding can, at times, be used to help states and locales develop such plans, revealing the intricate connections between these three elements. As is displayed in Figure 9-1, community relocation is a multilevel process, each level with different roles and responsibilities. As such, the

SOURCE: Weber, A., & Moore, R. (2019). Going under: Long wait times for post-flood buyouts leave homeowners underwater. Natural Resources Defense Council. https://www.nrdc.org/resources/going-under-long-wait-times-post-flood-buyouts-leave-homeowners-underwater

sections of this report, broken down by level (federal, state, regional, local), cover funding, policy, and planning to different extents.

The federal section primarily discusses funding, as the federal government’s main role in the current landscape is to provide funding for states and communities. Because most of the funding comes from the federal level, the policies that stipulate eligibility are also key at this level, and community actions are dictated by them. Notably, the financial costs of community-driven relocation vary greatly from case to case depending on a multitude of factors (e.g., distance of move, current price of supplies, community expectations such as for housing types). The costs of relocation for several case studies are noted in Chapter 3. At the state level, the discussion centers on state programs, which can help to facilitate relocation, particularly by connecting communities to federal and other funding and to state plans (e.g., Louisiana’s Coastal Master Plan), which mention relocation as an adaptation strategy. The state-level programs discussed in this chapter vary in the amount of planning for relocation they conduct. For example, Blue Acres proactively purchases undeveloped land and works to identify contiguous parcels in order to enhance the benefits of relocation while other state programs do not. The regional coordination section covers planning on topics that affect multiple jurisdictions (e.g., counties, cities, states). The landscape of regional planning entities in Gulf states does not currently incorporate community-driven relocation but rather the structures and networks which, if desired by members, could be leveraged to plan for community-driven relocation. At the local level, there are buyout programs that may draw from local funding sources and therefore have more flexible spending guidelines and that in some instances serve a similar role as state buyout programs. At this level there is also a heavier focus on detailed land-use planning.

FEDERAL AGENCIES, AUTHORITIES, AND POLICIES

This section looks at the agencies and programs through which the federal government offers support to individuals and communities dealing with changes to their home areas. It is divided into examples of agencies and programs that follow a disaster-response model and those that follow a more proactive model; the section then briefly discusses nonfinancial technical assistance provided by these federal agencies to state and local governments.

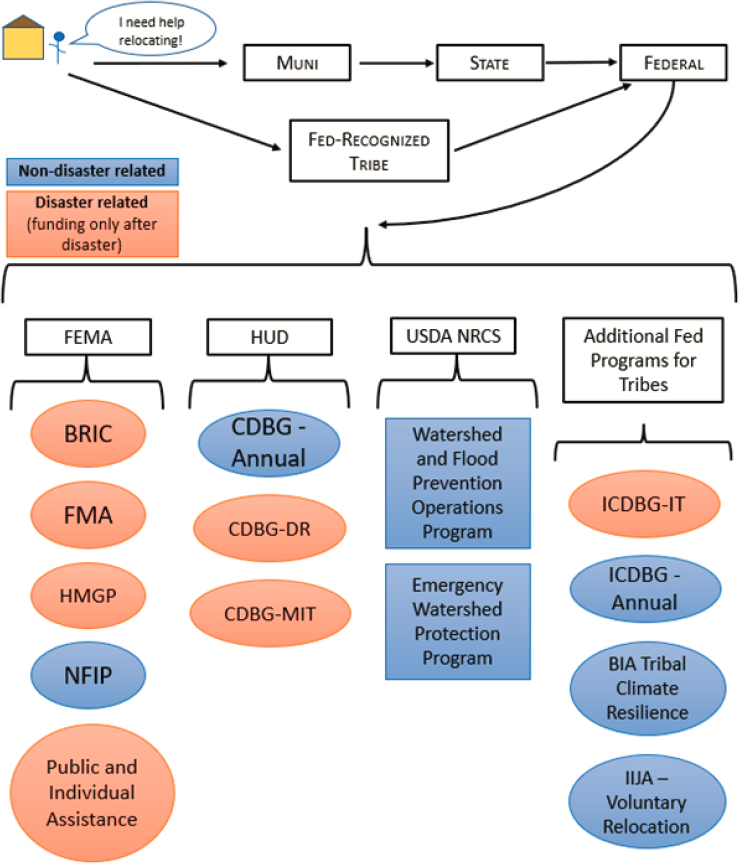

Maze of Potential Assistance

As will be demonstrated by this section’s summaries of federal agencies and programs, and the current set of laws and policies, communities

have to navigate a complex maze centered mainly on funding buyouts of individual households while allowing for enough time and money to obtain replacement housing. Funding distributed through competitive grant applications is too often episodic and unpredictable, does not provide a stable base of resources for planning, is resource intensive for communities, and may unfairly privilege the communities and households with the best grant writers over those most in need (more in Chapter 10). Figure 9-2 depicts the array of federal programs that threatened communities may navigate when pursuing relocation. Each of the agencies displayed in Figure 9-2, and their relevance to community-driven relocation, are explained in more detail in this section. This “unclear federal leadership” was identified as the “key challenge to climate migration as a resilience strategy” in a recent report by the Government Accountability Office (GAO, 2020a). A discussion of specific challenges with this current framework and opportunities to overcome them is in Chapter 10.

Disaster-Related Agencies

Much of the federal-level funding for relocation has been allocated for discrete purposes as components of larger federal post-disaster efforts or efforts otherwise directly linked to the occurrence of a specific disaster (as opposed to ongoing change over time and/or proactive measures taken against the threat of that sort of change).

Federal Emergency Management Agency

With a history of providing disaster relief tracing back to 1803, FEMA’s mission is to “[help] people before, during and after disasters.”1 FEMA funding is authorized through the Robert T. Stafford Disaster Relief and Emergency Assistance Act of 1988 (Stafford Act, P.L. 100-707) and its amendments.2 As discussed below, FEMA funding is tied to a presidential disaster declaration, meaning that the programs administered by FEMA largely conform to a post-disaster funding model. This can curtail efforts to proactively prepare for anticipated hazards (including relocating away from hazardous areas). Additionally, the slow effects of climate change, including erosion and sea level rise, are not eligible to be presidentially declared disasters. Thus, FEMA funds are often off-limits to individuals or communities seeking to proactively address climate-related threats (GAO, 2009;

___________________

1 More information about FEMA’s mission, values, and history is available at https://www.fema.gov/about

2 These amendments include the Disaster Mitigation Act of 2000 (HR 707, 106th Congress, P.L. 106-390) and the Disaster Recovery Reform Act in 2018 (HR 4460, 115th Congress).

NOTES: Municipality (Muni); Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA); Building Resilient Infrastructure and Communities (BRIC); Flood Mitigation Assistance grant program (FMA); Hazard Mitigation Grant Program (HMGP); National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP); Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD); Community Development Block Grant (CDBG); CDBG Disaster Recovery (CDBG-DR); CDBG Mitigation (CDBG-MIT); U.S. Department of Agriculture Natural, Resources Conservation Service (USDA NRCS); Indian Community Development Block Grant (ICDBG); ICDBG Imminent Threat (ICDBG-IT); Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA); Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA).

SOURCE: Committee generated.

Shen & Ristroph, 2020). Furthermore, this type of funding model (and the annual competition model used by the Building Resilient Infrastructure and Communities [BRIC] program) does not provide the consistent predictable funding that planning for community-driven relocation warrants.

There is some opportunity, however, to use FEMA assistance programs for community-wide relocation, despite funds often being made available only in the immediate aftermath of a presidentially declared disaster. For example, Alatna Village in Alaska was able to relocate using funds from FEMA’s HMGP after flooding disaster declarations in 1994 (GAO, 2009). FEMA administers several assistance programs, most of which include relocation as an eligible action. Those most relevant to this report include the Public Assistance (PA) Program, Individuals and Households Program (IHP),3 and Hazard Mitigation Assistance (HMA) programs.4 HMA programs include the HMGP, BRIC, and Flood Mitigation Assistance grant program (FMA). Eligibility for each program, except FMA, requires a prior disaster declaration. BRIC requires a disaster declaration in the past seven years. Thus, FMA and BRIC are formally classified by FEMA as non-disaster-related programs but are discussed in this section to keep FEMA programs together. Additionally, each of these programs (minus IHP) require applicants and subapplicants to have a FEMA-approved HMP usually at the time of application and when funds are distributed. HMGP also requires an approved plan at the time of the disaster declaration.

The PA Program is aimed at providing immediate relief to disaster-affected communities to restore disaster-damaged facilities. Unlike HMGP, which allows funds to be used for damaged and non-damaged facilities, PA funds can only be used to repair damaged facilities. Relocation is an approved project under this program if the relocation meets certain conditions including that the relocation is cost-effective and the property is subject to repeated damage (e.g., is located in a Special Flood Hazard Area; FEMA, 2020b). IHP funding is meant to help individuals and households to cover expenses related to basic needs (such as housing) and disaster recovery efforts that are not covered by insurance, including moving and expenses.5

HMGP funding is intended to “support mitigation activities that reduce or eliminate potential losses” and foster “resilience against the effects of disasters” (FEMA, 2023c, p. 28); however, funds are only made available after

___________________

3 More information about the PA Program is available at https://www.fema.gov/assistance/public, and more information about the IHP is available at https://www.fema.gov/assistance/individual/program

4 More information about HMA programs is available at https://www.fema.gov/fact-sheet/summary-fema-hazard-mitigation-assistance-hma-programs

5 More information about IHP is available at https://www.fema.gov/assistance/individual/program

a disaster declaration. HMGP distributes an estimated percentage of federal disaster assistance, typically 15 percent of total federal disaster costs, to the applicant (state, tribal, and territorial governments, and the District of Columbia) on a sliding scale.6 States with an approved Enhanced Hazard Mitigation Plan (a plan that exceeds the basic requirements) receive an additional 5 percent (FEMA, 2022b). Successful applicants then establish their own funding parameters within FEMA’s eligibility constraints and distribute this assistance to communities (subapplicants). In the past 30 years, HMGP has obligated more than 3.6 billion dollars for property acquisition (FEMA, 2023f). In a property acquisition, typically the land is purchased and the structure is either demolished or relocated. Significantly, entities are eligible for this mitigation funding only in the wake of a specific disaster and cannot apply to use the funds for projects that might mitigate the impact of future hazards, unless they have recently experienced a disaster.

In an effort to be more proactive, FEMA established an annual competitive grants program, the Pre-Disaster Mitigation (PDM) Grant Program,7 to support planning for and implementing measures to reduce future risk from natural hazards at the state, local, tribal, and territorial government levels. In 2020, the BRIC program8 essentially replaced PDM and shifted its focus to nature-based solutions9 rather than the large-scale acquisition of hazard-prone housing (FEMA, 2021a). BRIC is funded as a percentage of the total disaster funding allocated by Congress in the previous year, or through one-time appropriations, such as the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act of 2021 (IIJA). This approach perpetuates a system in which a community’s eligibility is determined by past disasters rather than future need as determined by projected vulnerabilities due to climate change. Furthermore, like any competitive grant program, BRIC does not provide the predictability in future funding needed across all states and localities. Competitive processes also often exacerbate and widen gaps between need and access to funding (see Chapter 10).

___________________

6 More information about the FEMA-approved HMPG is available at https://www.fema.gov/grants/mitigation/hazard-mitigation

7 More information about the PDM is available at https://www.fema.gov/grants/mitigation/pre-disaster

8 More information about the BRIC program is available at https://www.fema.gov/grants/mitigation/building-resilient-infrastructure-communities

9 “Nature-based solutions are actions to protect, sustainably manage, or restore natural ecosystems, that address societal challenges [e.g., climate change, disaster risk reduction …] providing human well-being and biodiversity benefits.” Nature-based solutions are an alternative to grey or manmade infrastructure solutions. One example is planting coastal trees as a method of reducing storm impact. More information about nature-based solutions is available at https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/feature/2022/05/19/what-you-need-to-know-about-nature-based-solutions-to-climate-change

FEMA’s FMA10 is focused on flood hazards and does not require a prior disaster declaration. The program is authorized for reducing or eliminating the risk of repetitive flooding for buildings that are insured by the National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP) and thus funds buyouts only for that group of properties. In 2022, FMA launched the Swift Current Initiative11 with money from the IIJA.12 The intent of this initiative is to expedite money to “disaster survivors with repetitively flooded homes” to help them become more flood resilient.13 Only NFIP-insured properties designated as Severe Repetitive Loss, Repetitive Loss, or Substantially Damaged are eligible.14 The initiative provided 60 million dollars in fiscal year 2022 across Louisiana, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, and Mississippi, the four states with the highest losses following Hurricane Ida. Eligible projects include the acquisition and subsequent demolition or relocation of eligible properties. Non-relocation flood mitigation projects (e.g., elevation and dry floodproofing) are also options under this program (FEMA, 2022b).

NFIP also has a history of investing in efforts to lower flood risks, such as through the Community Rating System (CRS), a program designed to reward communities that take actions to better manage flood risks beyond those required under the program. CRS has led to reduced overall losses and lower flood claims in participating communities (Gourevitch & Pinter, 2023; Highfield & Brody, 2017; Kousky & Michel-Kerjan, 2017). Additionally, in 2020, Congress passed the Safeguarding Tomorrow through Ongoing Risk Mitigation Act (P.L. 116-284), which authorizes FEMA to award grants to states, federally recognized tribes, and territories so that these smaller governmental entities can establish and administer revolving loan funds aimed at promoting resilience and available to local communities. This system differs from existing HMA programs in that the state, territory, or federally recognized tribe is responsible for making funding decisions and awarding loans to local governments rather than routing local government subapplications to FEMA for approval. FEMA’s program for administering these grants, the Safeguarding Tomorrow Revolving Loan

___________________

10 More information about the FMA is available at https://www.fema.gov/grants/mitigation/floods

11 More information about the Swift Current Initiative is available at https://www.fema.gov/grants/mitigation/floods/swift-current

12 More information about the IIJA is available at https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2021/11/06/fact-sheet-the-bipartisan-infrastructure-deal/

13 Ibid.

14 More information about Severe Repetitive Loss, Repetitive Loss, and Substantially Damaged is available at https://www.fema.gov/txt/rebuild/repetitive_loss_faqs.txt

Fund Program,15 received an initial sum of 500 million dollars over five years, authorized by Congress via the IIJA. FEMA has initiated the first notice of funding opportunity for these grants, and eligible entities are passing legislation and applying for monies with which to establish locally focused revolving loan funds. To alleviate one of the largest barriers for states and localities, FEMA does not require the use of benefit-cost analysis to determine project eligibility for this program, and loans may be used to cover nonfederal match costs for other HMA grants. (Benefit-cost analysis and nonfederal matches will be discussed in more detail in Chapter 10.)

Department of Housing and Urban Development

HUD was created in 1965 through the consolidation of five agencies, including the Federal Housing Administration and the Community Facilities Administration, with the intent of creating one federal agency through which to address “urban problems including substandard and deteriorating housing.”16 Although HUD’s primary purpose is not relocation or climate resilience, the Community Development Block Grant (CDBG) Program “supports community development activities to build stronger and more resilient communities,”17 and funding under this umbrella can be (and has been) used for community relocation (GAO, 2020a). In addition, HUD recently released an implementation guide for community-driven relocation (HUD, 2023a). The guide details relocation mechanisms, HUD and FEMA funding opportunities, and a six-step process for community-driven relocation with examples. The CDBG funding categories most relevant for relocation are CDBG Mitigation (CDBG-MIT) Program funds and CDBG Disaster Recovery (CDBG-DR) Program funds, both of which are tied to recent disasters, and neither of which receives regular annual congressional appropriations. Components of HUD’s CDBG Program may receive congressional funding after a disaster, while also having an annual competitive grants program (discussed below). Notably, funds from these two programs “have a statutory focus on benefiting vulnerable lower-income people and communities and targeting the most impacted and distressed areas” (HUD, 2019, p. 45838).

Funds for CDBG-MIT were first appropriated by Congress in 2018 for disasters that occurred in 2015, 2016, and 2017. The program provides

___________________

15 More information about the Safeguarding Tomorrow Revolving Loan Fund Program is available at https://www.fema.gov/grants/mitigation/storm-rlf

16 More information about the history of HUD is available at https://archives.hud.gov/hud50/hud50.hud.gov/hud_history_timeline/index.html

17 More information about the CDBG is available at https://www.hudex-change.info/programs/cdbg/

grants to areas recently impacted by qualifying disasters to carry out “activities to mitigate disaster risks and reduce future losses” (HUD, 2019, p. 45838). CDBG-MIT funds18 can be used for post-disaster buyouts (Smith, 2014). Grantees must develop an action plan for their proposed projects and these plans must reference FEMA-approved HMPs. Funds can be used to update HMPs and for other planning activities, including integrating mitigation plans with other planning initiatives (HUD, 2019). Thus, if a community or state decides to incorporate community-driven relocation into their HMP, the associated planning is an activity that could be covered by CDBG-MIT funds.

CDBG-DR19 is another such program that relies on competitive grants to disburse funds. It is funded as a supplemental congressional appropriation and can be used to fund the nonfederal cost-share that is required by other federal disaster assistance programs. After Congress appropriates funding to CDBG-DR, HUD formally announces the availability of CDBG-DR awards and associated rules in the Federal Register. CDBG-DR grants are subject to laws that apply to all CDBG programs. Eligible activities that grantees have undertaken with CDBG-DR grants include relocation of displaced residents, acquisition of damaged properties, rehabilitation of damaged homes and public facilities (e.g., neighborhood centers and roads), and certain hazard mitigation activities (HUD, 2023b).

Separate funding is reserved for federally recognized tribes through two programs, the Indian Housing Block Grant and the Indian Community Development Block Grant (ICDBG) Program.20 Notably, many U.S. Gulf Coast tribes are not federally recognized, meaning they cannot benefit from these programs. Under ICDBG, Imminent Threat Grants are available on a noncompetitive basis to recognized tribes for a problem “which if unresolved or not addressed will have an immediate negative impact on public health or safety” (Title I of the Housing and Community Development Act of 1974, as amended, 42 U.S.C. 5301, 2023, § 1003.4). For example, Newtok, Alaska, received funding from ICDBG Imminent Threat Grants to aid in its relocation efforts (Ristroph, 2021; see Chapter 3 for more). Because of the focus on the imminent nature of the threat, this report considers these grants to be disaster-related (i.e., contingent on a specific event rather than ongoing).

There is also some precedent for HUD funds, outside of those described above, being used to support community relocation in the wake of disasters

___________________

18 More information about HUD’s CDBG-MIT funding is available at https://www.hudex-change.info/programs/cdbg-mit/overview/

19 More information about CDBG-DR funding is available at https://www.hudex-change.info/programs/cdbg-dr/overview/

20 More information on both grant programs is available at https://www.hud.gov/program_offices/public_indian_housing/ih/grants

even though they were not labeled as such. An appropriations bill that followed Hurricane Sandy allocated 16 billion dollars21 for HUD’s Community Development Fund (the program in which CDBG sits) to be used for “disaster relief, long-term recovery, restoration of infrastructure and housing, and economic revitalization” (P.L. 113-2, 127 Stat 36, January 29, 2013). These funds were limited to jurisdictions with presidentially declared disasters from 2011 to 2013. For example, through HUD’s National Disaster Resilience Competition (NDRC), Louisiana received 48 million dollars in CDBG funds to relocate the community of Isle de Jean Charles (see Chapter 3).22 Additionally, with NDRC, state funding, and innovative partnerships with philanthropic organizations, such as Foundation for Louisiana, a total of 47.5 million dollars was available for Louisiana’s Strategic Adaptations for Future Environments (LA SAFE)23 (Spidalieri & Bennett, 2020c).

Although the majority of the HUD programs described above are tied to disasters, it is worth noting the range of resilience actions that HUD has undertaken, including addressing issues of housing, transportation, education, community centers, and implementing flood risk reduction measures to multiple hazards, including tidal flooding, stormwater, and episodic storm events. By doing so, HUD has demonstrated the ability to provide a more comprehensive approach to resilience in comparison with other federal programs whose funding might be used for relocation. This is important considering the numerous elements (e.g., housing, transportation, and education) that must be considered in community-driven relocation.

Agencies Not Primarily Disaster-Related

A number of other federal programs are generally proactive, unlike disaster-related programs, but they do not have sufficient funding for community relocations that are needed now or to prepare for future climate conditions (Howe et al., 2021).24

U.S. Army Corps of Engineers

The Civil Works Program of USACE is the main federal agency in charge of flood risk management (FRM), which stands as one of its three

___________________

21 Which was reduced to 15.2 billion dollars as a request of sequestration (GAO, 2014).

22 More information about the Isle de Jean Charles resettlement is available at https://isledejeancharles.la.gov/

23 More information about LA SAFE is available at https://lasafe.la.gov/

24 As noted above, although BRIC and FMA are designated as pre-disaster grant programs, they are included in the previous section because their funding is tied to past disasters.

core missions.25 Authorized through the 1960 Flood Control Act (P.L. 86-645) and subsequent amendments, USACE statutes require various authorizations through the Water Resources Development Act to work on individual or multiple water projects.26 The Rivers and Harbor Act of 1968 (P.L. 90-483) authorized USACE to assist states and localities with water resource development projects and beach erosion control and to conduct flood control surveys. It is also the authority under which USACE conducts nonstructural projects, which have included community relocation. However, the requirement that USACE seek congressional authorization to address flood risk in a specific locality, with no organic statute governing overall authority of USACE to determine its own agenda, has resulted in piecemeal and inequitable distribution of FRM projects.

USACE’s FRM program does evaluate, recommend, and fund nonstructural measures, including buyouts and relocations, to reduce the risks of flooding from fluvial or coastal sources, and it authorizes “relocation with a view toward formulating the most economically, socially, and environmentally acceptable means of reducing or preventing flood damages” (33 U.S.C., § 701b-11). To this end, USACE’s National Nonstructural Committee advises USACE internally on policies and processes to increase the capacity of USACE to implement nonstructural measures.27

Although used sporadically in the past, USACE’s use of nonstructural measures is growing, as indicated by the designation of 296 million dollars largely for elevating and floodproofing structures through the Southwest Coastal Louisiana Project28 (through IIJA; Renfro, 2022). However, notably, relocation is not identified as one of the nonstructural measures that will be pursued in this project. Furthermore, the Coastal Texas Protection and Restoration Feasibility Study final report (USACE & Texas General Land Office, 2021, p. 35) finds that “managed retreat” was “determined not to be a practicable and standalone solution” to reduce impacts from a wide array of coastal hazards but that “managed retreat” could “work in combination with a structural system to manage residual risk and address changes in future conditions.” These examples show that while there may be increasing attention on nonstructural flood management measures, community relocation is not a predominant option.

___________________

25 USACE’s two other core missions are core missions support commercial navigation and the restoration of aquatic ecosystems. More information about the FRM mission is available at https://www.usace.army.mil/Missions/Civil-Works/Flood-Risk-Management/

26 More information about the Water Resources Development Act is available at https://www.usace.army.mil/Missions/Civil-Works/Water-Resources-Development-Act/

27 More information on the role of the National Nonstructural Committee is available at https://www.usace.army.mil/Missions/Civil-Works/Project-Planning/nnc/

28 More information on the Southwest Coastal Louisiana Project is available at https://cims.coastal.louisiana.gov/outreach/Projects/SWCoastal

Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS)

The U.S. Department of Agriculture’s NRCS administers several programs related to flooding and erosion control projects and watershed planning. The Watershed and Flood Prevention Operations program29 and the Emergency Watershed Protection (EWP) program30 both allow for structural measures, buyouts, and relocations to prevent erosion or reduce risk exposure. For a community to receive funds or technical assistance from NRCS watershed programs, a local sponsor (e.g., city, county, federally recognized tribe), working through their local NRCS office, must first demonstrate project feasibility. Once feasibility has been assessed, NRCS may authorize the proposed project, and then resources are made available to sponsors. EWP does require that an NRCS State Conservationist declare a “local watershed emergency,” but it does not require an official federal or state disaster declaration.31 Additionally, individual landowners who would like assistance from EWP must apply through a local sponsor. Funding from NRCS was used in the purchase of flood-damaged properties in Pecan Acres, a neighborhood in Pointe Coupee Parish, Louisiana, that had flooded almost 20 times in the past three decades (Louisiana Office of the Governor, 2023).

U.S. Department of the Interior (DOI)

The Bureau of Indian Affairs of DOI has small funding streams specific to tribes, inducing annual competitive grants awarded by the Tribal Climate Resilience Annual Awards Program.32 Previously, this program only provided limited funds for planning, travel, and capacity building, but the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law enacted as the IIJA (P.L. 117-58) in 2021 provided 216 million dollars for climate resilience programs, with 130 million dollars for community relocation (DOI, 2022a; Flavelle, 2022). This funding has enabled Alaska tribes, including Newtok Village and the Village of Chefornak, to plan and carry out relocation efforts in a proactive way (Bureau of Indian Affairs, 2022). However, there are only 11 federally

___________________

29 More information on the Watershed and Flood Prevention Operations program is available at https://www.nrcs.usda.gov/programs-initiatives/watershed-and-flood-prevention-operations-wfpo-program

30 More information on the EWP program is available at https https://www.nrcs.usda.gov/programs-initiatives/ewp-emergency-watershed-protection

31 Ibid.

32 More information on the Tribal Climate Resilience Annual Awards Program is available at https://www.bia.gov/service/tcr-annual-awards-program

recognized tribes in the Gulf states,33 so many Indigenous communities in need were not eligible to apply for these funds, and no tribe in the Gulf states has yet received funding (DOI, 2022b).

In partnership with FEMA, DOI also leads the new Voluntary Community-Driven Relocation program to assist tribal communities severely affected by climate-related environmental threats. At the November 30, 2022, White House Tribal Nations Summit, the Biden Administration committed the government to providing noncompetitively awarded funding to various federally recognized tribes, including the Chitimacha Tribe in Louisiana (DOI, 2022a).

U.S. Department of Transportation (DOT)

In contrast to several disaster-related programs, the Highway Trust Fund of DOT is distributed to all states annually for state and local priorities.34 Although also inadequately funded in relation to needs, this consistent source of funding has allowed state and local governments to build and maintain the staffing capacity and expertise needed to implement and maintain infrastructure over time. Adopting a funding model wherein funds are distributed annually to be used for state and local priorities provides a consistent source of funding that allows states and local governments to strategically pursue their own policies and plans, particularly those relating to capital improvements, in a way they might not be able to do with disaster-based funding, which is episodic. Which is to say, adopting a funding model that more closely resembles the DOT Highway Trust Fund might be beneficial for disaster and relocation planning.

The IIJA designates several DOT funding sources for transportation improvements, in addition to the governmental funding for the relocation of tribal communities via the Bureau of Indian Affairs described above. Although these DOT programs are not directly related to relocation, they could be relevant to receiving communities for building up more sustainable and resilient transportation systems in anticipation of growing populations. One of these funding sources is the Rebuilding American Infrastructure

___________________

33 This list includes tribes that do not reside along the Gulf portion of Gulf states (e.g., Ysleta del Sur Pueblo, El Paso, Texas): Poarch Band of Creek Indians (Alabama), Seminole Tribe of Florida, Miccosukee Tribe of Indians (Florida), Coushatta Tribe of Louisiana, Jena Band of Choctaw Indians (Louisiana), Tunica-Biloxi Indian Tribe (Louisiana), Chitimacha Tribe of Louisiana, Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians, Alabama-Coushatta Tribe of Texas, Ysleta del Sur Pueblo (Texas), and Kickapoo Traditional Tribe of Texas.

34 More information about the Highway Trust Fund is available at https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/policy/olsp/fundingfederalaid/07.cfm

with Sustainability and Equity Discretionary Grant program.35 This is not a new source, but 1.5 billion dollars was allocated in the IIJA.36 The IIJA also created a new Rural Surface Transportation grant program, allocating 300 million dollars37 to “increase connectivity; to improve the safety and reliability of the movement of people and freight; and to generate regional economic growth and improving quality of life” (§11132, IIJA). The IIJA also increases DOT’s funding for the Transportation Alternatives Program that supports “pedestrian and bike infrastructure, recreational trails, safe routes to school and more.”38 Again, this funding could be relevant in preparing receiving communities to offer sustainable transit options to new and current residents.

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA)

In an effort to mitigate a different set of environmental risks than those related to climate change, EPA grants the authority to fund permanent relocations of residents, buildings, and community facilities as a remedial action39 to protect against the effects of pollution through its Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act of 1980 (CERCLA; P.L. 96-510), also known as its Superfund Program. A presidential determination is required to the effect that relocation is more cost-effective and environmentally preferable to alternative management strategies to protect public health from exposure to hazardous substances. Similar authorities exist under the EPA National Contingency Plan,40 and implementation of EPA’s relocation policy is governed by the Uniform Relocation Assistance and Real Property Acquisition Policies Act of 1970 (P.L. 91-646), which provides “for uniform and equitable treatment of persons displaced from their homes, businesses, or farms by Federal and federally assisted programs and to establish uniform and equitable land acquisition policies for Federal and federally assisted programs.”41 EPA uses the

___________________

35 More information about the Rebuilding American Infrastructure with Sustainability and Equity program is available at https://www.transportation.gov/RAISEgrants/about

36 More information about IIJA is available at https://www.transportation.gov/bipartisan-infrastructure-law/fact-sheet-equity-bipartisan-infrastructure-law

37 Ibid.

38 Ibid.

39 More information about EPA grants to support permanent relocation is available at https://www.epa.gov/superfund/superfund-relocation-information

40 More information about the National Contingency Plan is available at https://www.epa.gov/emergency-response/national-oil-and-hazardous-substances-pollution-contingency-plan-ncp-overview

41 More information about the Uniform Relocation Assistance and Real Property Acquisition Policies Act of 1970 is available at https://www.govinfo.gov/app/details/COMPS-1432#

services of USACE and the Bureau of Reclamation to assist in conducting relocations.

As of October 2019, permanent relocations of businesses or residences had only been implemented by EPA at “33 of the more than 1,700 final and deleted sites on the Superfund National Priorities List” (EPA, 2019a, p. 1). “Of those 33, only 11 sites” were due to human health concerns; 19 of the remaining 22 relocations “were for engineering solutions” required for a cleanup remedy (EPA, 2019a, p. 1). This is reflective of CERCLA’s preference for cleanup solutions over permanent relocation (Scott, 2014).

Under CERCLA, the decision to conduct a relocation is made following an EPA technical analysis of available remedies. EPA has created several opportunities for community involvement and provides extensive information on its residential relocation policies on its Superfund relocation information website.42 EPA stresses that community involvement must occur early and frequently throughout the relocation process. When a permanent relocation is under consideration, EPA offers access to an independent relocation technical expert or advisor to assist residents and businesses.

The consequences of EPA’s relocations have not been well documented. Documentation that does exist shows mixed results, with a need for further attention to the consequences of these relocations. In the case of the Escambia Wood site in Florida, the EPA Office of Inspector General conducted a follow-up survey of a subset of homeowners who were relocated (Office of Inspector General, 2004). Respondents reported a number of concerns, including inadequate compensation for properties and a lack of transparency on how appraisals were carried out. Of note, people who identified their own new homes rather than moving into the homes that the government provided were more satisfied.

It has been suggested that a legal framework analogous to the CERCLA provision could be developed in the context of relocating communities affected by climate change (Scott, 2014). CERCLA can be used to support relocation for communities that face climate hazards and are near a Superfund site or other affected sites, such as areas close to chemical spills during disasters. Scott (2014) suggests that such a law applying to environmentally displaced persons could be funded through a tax or fee on greenhouse gas emissions. This example demonstrates an existing relocation framework from which lessons can be drawn and applied to making community-driven relocation an achievable adaptation strategy.

___________________

42 More information about Superfund community involvement tools and resources is available at https://www.epa.gov/superfund/superfund-community-involvement-tools-and-resources

Justice40 Initiative

The Justice40 Initiative is an unprecedented commitment by the federal government, established through Executive Order 14008 in 2021, to make “40 percent of overall benefits of certain federal investments flow to disadvantaged communities that are marginalized, underserved, and overburdened by pollution.”43 As the committee heard during the study’s workshops across the U.S. Gulf Coast, perhaps most starkly in Port Arthur, many of the communities facing environmental threats, such as increasingly destructive hurricanes, subsidence, and sea level rise, are also overburdened by industrial pollution (see Chapter 5). Thus, the White House’s push to increase the flow of federal funding to disadvantaged communities through Justice40 could also help to increase funding available to help these communities relocate if they choose to do so. Hilton Kelley, founder and director of Community In-power and Development Association Inc., spoke on this issue at the committee’s first workshop:

The large number of emissions that were being dumped from the air, like sulfur dioxide, benzine, ethylene oxide—you name it and people in West Port Arthur breathe it. And we have scars to prove it. Many of us have died. Many of us are still suffering with cancer and respiratory problems like liver and kidney disease.

Every federal agency has been tasked with “identifying which of their programs are covered under the Justice40 Initiative, and to begin” reforming these programs so that they deliver benefits to marginalized communities and those overburdened by pollution.44 Under FEMA, these programs include BRIC and FMA (including the Swift Current Initiative); under HUD, they are CDBG-DR and ICDBG. Additionally, FEMA has been tasked with the oversight of the Community Disaster Resilience Zones Act, which seeks to identify and designate underserved communities and provide targeted assistance to help them reduce their risk to natural hazards and disasters.45 Although this is not a part of the Justice40 Initiative, it is recommended that when designating these zones, FEMA align with the initiative.46 At

___________________

43 More information about the Justice40 Initiative is available at https://www.whitehouse.gov/environmentaljustice/justice40/

44 Ibid.

45 More information about the Community Disaster Resilience Zones Act is available at https://www.fema.gov/flood-maps/products-tools/national-risk-index/community-disaster-resilience-zones

46 More information about public input into the implementation of Community Disaster Resilience Zones is available at https://www.fema.gov/fact-sheet/summary-request-information-implementation-community-disaster-resilience-zones

the time of this report’s publication, FEMA was developing a method to identify these areas and determine the types of assistance it might provide.

Federal Nonfinancial Technical Assistance for Flood Events

In addition to funding, federal agencies provide important resources to state and localities before, during, and after flood events (Smith, 2011; Snel et al., 2020, 2021). These resources include the provision of technical assistance or “programs, activities, and services provided by federal agencies to strengthen the capacity of grant recipients and to improve their performance of grant functions” (GAO, 2020c, p. 3). Technical information is provided through training and education related to, for example, how to reduce disaster damage and develop and assess mitigation plans,47 and the delivery of useful localized information, such as flood maps. However, there are problems with some of the information. For instance, many of FEMA’s flood maps are outdated and inaccurate, and they do not account for future flood risk (Kuta, 2022; Lehmann, 2020; Marsooli et al., 2019). The work to identify future climate predictions from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) is not integrated into other agencies’ decision-making processes and funding allocations.

In some instances, a lack of data and information-sharing requirements from governmental agencies has opened the door for other stakeholders to step in and provide information about the scale or nature of potential environmental threats. For example, the United States does not have a federal requirement for home sellers to disclose information to prospective buyers about a property’s flood risk, flooding history, or previous flood damage (Scata, 2019). In the absence of a federal requirement, flood risk disclosure has become available on real estate market and other websites, which may incentivize people to move away from or not purchase properties in flood-prone areas.48 This information on flood risk does little to help those located in these areas who seek to move, however, and in fact, may further hamper their ability to do so. For example, if one’s home is identified as being in a high-risk area via the Zillow app and such data lack connection to planned capital projects to reduce local flood risks, one’s home is still devalued. Additionally, risk information coming from multiple entities without clearly defined roles and uses, and with varying levels of robustness, can cause confusion for users. While raising risks is a valuable

___________________

47 More information about examples of technical assistance provided by FEMA is available at https://www.fema.gov/grants/mitigation/building-resilient-infrastructure-communities/direct-technical-assistance/communities

48 One such organization is Risk Factor; more information is available at https://riskfactor.com/

contribution, risks without context and optionality present more challenges for the very communities already facing those risks. Without more federal support to contextualize risk data, organizations seeing market demand for this information will continue to provide resources without federal or state coordination on the implications of those data.

In another case, the Gulf Coast Community Design Studio (GCCDS) realized that many coastal residents devastated by Hurricane Katrina’s storm surge were unsure of the cost of reconstruction. GCCDS sought to reduce this uncertainty for residents in Biloxi, Mississippi, by creating a map of affected areas at the parcel scale that visually depicted the projected heights to which houses would need to be rebuilt to comply with FEMA’s advisory base flood elevation maps; see Figure 9-3. Such advisory base flood elevation maps are often created following a major disaster as an update to pre-existing flood insurance rate maps, so that community officials and residents have the most recent information available to inform post-disaster reconstruction standards. The image in Figure 9-3 was created by overlaying planimetric data at the parcel level and projected elevation estimates to provide more useful information to residents as they sought to determine how high they would be required to elevate their homes, something an advisory base flood elevation map does not provide. Communities, however, cannot depend on regional institutions to provide pro bono services to understand risks and associated costs of risk reduction. More substantive investments in risk awareness, preparedness, and community-driven decision making are necessary.

In addition to gaps in the provision of locally contextualized data to improve decision making, significant problems exist relative to the creation of federal disaster assistance policies that are flexible enough to better reflect unique localized conditions. Several studies have suggested methods of improving federal flood mitigation policies, including strengthening partnerships between relevant actors; considering bottom-up and participatory processes for policy making and resilience planning and implementation; and recognizing key social factors (i.e., factors that influence where households decide to locate) to foster community acceptance, avoid administrative burdens on individuals, and prevent unfavorable socioeconomic outcomes (Greer & Trainor, 2021; Hemmati et al., 2021; Suykens et al., 2019). Evident within these studies is the need for more, and more specific, federal assistance to establish collaborative structures and to substantiate the coordination required for the degree of risks and likely needs for mitigation measures.

SOURCE: Gaspar, C. (2007). GISCorps volunteer teaches GIS to Gulf Coast community design studio team in Biloxi, Mississippi. GISCorps. https://www.giscorps.org/biloxi_022/#

STATEWIDE RELOCATION AND PLANNING EFFORTS

This section first looks across the United States at what several states have done to address the need for relocation in the face of climate change. It then discusses in detail a range of efforts in Texas.

National Overview

Several coastal states and local governments outside the Gulf region have developed long-term buyout programs or offices such as Blue Acres in New Jersey and ReBuild NC in North Carolina to administer federal buyout funding and conduct related long-term planning (e.g., identifying high flood risk areas). In 1995, New Jersey’s Department of Environmental Protection created the Blue Acres program, a revolving grant program that is designed to relocate families whose homes are at risk of flooding and to convert these lands to parks, natural flood storage, and open space.49 The program has two primary aims: to provide post-disaster funding to assist flood-damaged homes, and to proactively acquire land that has been damaged in the past or to acquire land that is prone to future damages and can serve as a means to protect adjacent communities (see Chapter 3). Much of the program’s funding comes from FEMA’s HMGP and HUD’s CDBG-DR (see Chapter 3 for more information about Blue Acres funding).

The North Carolina Office of Recovery and Resiliency, or ReBuild NC, was created following Hurricane Florence to lead the state’s recovery efforts. The office manages almost a billion dollars in HUD CDBG-DR and CDBG-MIT funding through several long-term disaster recovery programs that assist homeowners affected by disasters.50 Through grants and loans, it supports rebuilding, replacing, relocating, or elevating damaged homes, while collaborating with local governments and organizations to enhance resilience, including infrastructure, ecosystems, and the well-being of residents. One of ReBuild’s NC’s programs is the Strategic Buyout Program, allowing eligible homeowners in flood-prone areas to sell their homes and relocate to safer areas, with purchased properties transformed into green spaces maintained by the local government. The primary funding for this program comes from CDBG-MIT, but CDBG-DR funds may also be used for “housing counseling activities and future program costs” (North Carolina Office of Recovery and Resiliency, 2023, p. 9).

State programs like Blue Acres and ReBuild NC’s Strategic Buyout Program are unique because they are able to address shortfalls in federal programs. These ongoing programs facilitate buyouts across the state by pulling together funding from, at times, multiple federal (and state, in

___________________

49 More information about Blue Acres is available at https://dep.nj.gov/blueacres/

50 More information about ReBuild NC is available at https://www.rebuild.nc.gov/about-us

the case of Blue Acres) agencies and partnering with local organizations to address the numerous elements of relocation. For example, Blue Acres partnered with local nonprofits to help individuals cover moving expenses and legal fees (FEMA, 2021a). This continuous funding allows for more long-term planning surrounding relocation than is often possible in the traditional federal buyout process, which also tends to take much longer to implement. For states without such programs, community organizations have emerged to fill gaps. For example, Buy-In Community Planning (a nonprofit founded in 2020) helps households with “planning for and relocating to safer areas.”51 (See Private and Public-Private Funding and Programs section below for more information.)

Some states have also developed programs to address more specific shortfalls of federal funding, including limitations tied to the provision of pre-disaster fair market value for prospective applicant housing—a limitation that hampers the ability of low-income homeowners to identify housing options of comparable size and good condition in areas of lesser hazard risk. To address this issue, North Carolina created the State Acquisition and Relocation Fund (SARF), which provides up to $50,000 in state money on top of a federal buyout offer through HMGP (North Carolina Department of Public Safety, 2019; Smith, 2014). Funding for SARF also comes from HMGP funds distributed following Hurricanes Matthew and Florence and is administered by the North Carolina Division of Emergency Management (Pender County, 2019). As such, in addition to being “located in a Special Flood Hazard Area” and being an “owner-occupied primary residence at the time of the event,” for a property to be eligible, it must have been approved for acquisition by FEMA HMGP during one of these two hurricanes (North Carolina Department of Public Safety & North Carolina Emergency Management, 2023). If SARF funds are used, the recipient is required to purchase a home in the county in which they resided but outside the floodplain (Smith, 2014). The stipulation tied to moving within the county sought to lessen the economic effects to the community and region tied to the loss of local tax base. In Rocky Mount and Kinston, North Carolina, this stipulation resulted in an estimated 90 and 97 percent of participants, respectively, staying within their municipality (Salvesen et al., 2018). The program’s ability to track the movement of residents and the ability of residents to maintain their new homes given their limited financial resources proved challenging in many circumstances (Salvesen et al., 2018). This state program, as well as several others, was codified by the North Carolina legislature to include the development of triggering mechanisms that will result in their application based on the severity of the disaster (Smith, 2014).

___________________

51 More information about Buy-In Community Planning is available at https://buy-in.org/aboutus

Most states have not historically planned for relocation, although this is slowly changing. Existing state plans tend to acknowledge the risks posed by climate change but offer limited funding and programmatic solutions to address the challenges. For example, the 2023 Louisiana Coastal Master Plan refers to the need for residents to move due to increasing flood risks and dedicates 11.2 billion dollars out of the 50-billion-dollar 50-year plan to implementing “nonstructural” measures (elevations, floodproofing, and voluntary relocation; Coastal Protection and Restoration Authority [CPRA], 2023b). However, since the original dedication of the funding in the 2012 Coastal Master Plan, the state implementation agency, CPRA, had not dedicated actual funding or staff capacity to develop this program. In the Fiscal Year 2024 Annual Plan, CPRA is funding nonstructural measures, with 3 million dollars a year for the next three years to develop the nonstructural program, in addition to funding 2.6 million dollars in Jefferson Parish and 13.7 million dollars over two years in Southwest Louisiana for home elevation projects (CPRA, 2023a). Although CPRA is now funding projects, the implementation of these measures will largely depend on other agencies, such as Jefferson Parish government or USACE, while CPRA works to develop its own implementation program in coordination with other state agencies. Furthermore, the 2024 Annual Plan does not include relocation or buyouts in any project descriptions (CPRA, 2023a).

States also set the priorities for federal HMGP funding (Smith et al., 2013)52 and have substantial flexibility in doing so (FEMA, 2016), assuming the states meet FEMA-codified requirements. Problematically, the entities and criteria used in setting these priorities are not always easily accessible or easily understood. For example, in Alaska, the State Hazard Mitigation Advisory Council sets priorities, but nothing is available on the state’s website about this entity or what it does for households. In Louisiana, the Governor’s Office of Homeland Security and Emergency Preparedness offers examples of eligible HMGP activities and lists regional liaisons, including State Applicant Liaisons to help subrecipients develop grant applications.53 In Texas, the Division of Emergency Management identifies priorities such as most impacted jurisdictions, vulnerabilities addressed, cost-effectiveness, and population served.54 In Florida, the Division of Emergency Management’s website notes that selection is delegated to

___________________

52 More information about the acquisition of property by a state using FEMA allocated HMGP funding after a flood event is available at https://www.fema.gov/press-release/20230502/fact-sheet-acquisition-property-after-flood-event

53 More information about HMGP in Louisiana is available at https://gohsep.la.gov/divisions/hazard-mitigation-assistance

54 More information about HMGP in Texas is available at https://statutes.capitol.texas.gov/Docs/GV/htm/GV.418.htm

each county’s Local Mitigation Strategy Working Group.55 However, there remains little transparency into how priorities are set and by whom, and the same types of information are not readily available in Alabama56 or Mississippi (although a direct contact with the Mitigation Officer is provided for both). Moreover, one important contextual consideration is that the rules associated with congressional and supplemental appropriations change in each federally declared disaster, making the process more challenging as states and local governments cannot always rely on past precedent.

State-level efforts to identify areas that could receive people who move are nascent. One example is the Bayou Culture Collaborative57 of Louisiana; this working group considers the transition of coastal residents and their culture to other communities and how communities can be better prepared to receive them. Although CPRA seeks to engage with these types of groups, these efforts have not yet been incorporated into state-level planning.

In contrast, the Blue Acres program in New Jersey is entwined with other state-level planning and is involved with both planning and implementing relocation in the state. Blue Acres emphasizes the use of housing counselors and the purchase of contiguous parcels to foster the preservation of community. Blue Acres buyouts are part of both the state’s disaster recovery and climate resilience strategies. To advance climate resilience, the program purchases undeveloped land as a proactive measure, using the land purchase to buffer adjacent communities from current or projected flooding, including flooding tied to sea level rise. Tenant relocation assistance was added to the program in 2017 to provide relocation assistance for renters being displaced by an acquisition of their rental property (Senate Bill 3401, 220th Legislature).

Another example can be found in North Carolina, where the governor’s office, the State Director of Emergency Management, and the state legislature provided one-time funding to support a team of faculty and students at the University of North Carolina and North Carolina State University to assist six underresourced communities in attending to a range of issues not addressed by federal and state programs. These issues include conducting

___________________

55 More information about HMGP in Florida is available at https://www.floridadisaster.org/dem/mitigation/hazard-mitigation-grant-program/

56 More information about HMGP in Alabama is available at https://ema.alabama.gov/hazard-mitigation-grant-program/

57 The Bayou Culture Collaborative is an informal group involving the Louisiana Folklore Society, the Center for Bayou Studies at Nicholls State University, the South Louisiana Wetlands Discovery Center, the Barataria-Terrebonne National Estuary Program, the Louisiana Division of the Arts Folklife Program, the University of Louisiana at Lafayette Center for Louisiana Studies, and other nonprofits. More information about the working group, Preparing Receiving Communities, is available at https://www.louisianafolklore.org/?p=1351

land suitability analysis to identify areas more appropriate for resettlement (see Chapter 8; Smith & Nguyen, 2021).

A Case Study of State Agencies and Buyouts: Texas

In Texas, the state provides funding support to local communities based on federal government allocations. Two significant state agencies in Texas that oversee buyout-related assistance to local communities are the Texas General Land Office (GLO) and the Texas Water Development Board (TWDB). These agencies are involved in buyout funding separately through both FEMA and HUD, and they both channel funds to local Texas communities. Harris County, which includes Houston, is the largest beneficiary of buyout funding from these agencies due to the scale of flood risk in the county. In Harris County, both TWDB and GLO work with various local agencies to implement buyout funding, obtaining support from different funding streams. In this way, TWDB and GLO help to reduce the burden on local entities to navigate the complex web of federal relocation funding.

GLO is responsible for administering and managing buyouts on behalf of HUD. Its main role is to act as a custodian of disaster recovery funding from HUD’s CDBG-DR Program and distribute these funds to local communities in need to execute buyout programs. Currently, GLO is disbursing funds through its Local Buyout and Acquisition Program58 specifically for the recovery efforts after Hurricane Harvey.

While GLO serves as the funding agency overseeing the buyout programs, the actual implementation of these programs is carried out by local agencies. In Harris County, this responsibility falls to the Harris County Community Services Department (HCCSD), which is accountable for various areas, including housing assistance, community development, and disaster recovery within the county. Within this department, the HCCSD Project Recovery program is responsible for implementing GLO’s buyout program in Harris County.59 The Project Recovery program is specifically designed to assist residents in recovering and rebuilding their homes following major disasters. It provides funding assistance that covers buyouts and relocation to support affected residents in their recovery efforts.

TWDB is a state agency that focuses on water resources planning and management. It plays a key role in addressing water-related challenges, including flood management, by providing financial assistance, technical support, and expertise to communities and agencies across the state. One

___________________

58 More information about the Local Buyout and Acquisition Program is available at https://recovery.texas.gov/grant-administration/grant-implementation/buyouts-and-acquisitions/index.html

59 More information about Project Recovery is available at https://harrisrecovery.org/

program administered by TWDB is the Flood Infrastructure Fund, which offers funding for various flood management initiatives, including property acquisition.60

To implement buyouts in Harris County, TWDB collaborates directly with the Harris County Flood Control District (HCFCD), a local agency responsible for managing flood control infrastructure and drainage systems in the county. Its primary objective is to mitigate flooding risks and safeguard lives and property from the impacts of severe storms. Under the Home Buyout Program of HCFCD, the agency submits applications to FEMA through TWDB and receives buyout funding from FMA (HCFCD, 2023). Through HCFCD, Harris County has the largest number of buyout properties in the most recent study (Mach et al., 2019).

The distinction between the roles and funding sources of HCCSD and HCFCD in Harris County highlights the fact that the fragmentation of relocation efforts at the federal and state levels trickles down to local communities. For example, the Project Recovery program by HCCSD specifically notes on its website that “[t]he Flood Control District also has a buyout program, but it is not the same as the Project Recovery program, and not everyone who qualifies for the HCFCD program will be eligible for the Project Recovery program.”61 Understandably, the two agencies focus on different issues (i.e., housing assistance and flood mitigation), but their separateness is not ideal. The decentralized approach and varying eligibility criteria among different agencies and programs underscore the confusion and administrative burdens of the lack of coordination and highlight the need for improved coordination and a more cohesive strategy for community-driven relocation at all levels of government.

REGIONAL COORDINATION IN THE GULF REGION

The Need for and Lack of Regional Coordination

For U.S. Gulf Coast states—Texas, Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama, and Florida—there is no interstate or intrastate jurisdictional authority for planning. Such an authority could offer collective support between the existing Gulf Regional Planning Commission62 (Mississippi); the Emerald

___________________

60 More information about the Flood Infrastructure Fund is available at https://www.twdb.texas.gov/financial/programs/FIF/index.asp

61 More information about the Project Recovery program by HCCSD is available at https://www.harrisrecovery.org/

62 More information about the Gulf Regional Planning Commission is available at https://grpc.com/about-grpc/

Coast Regional Council63 (Northwest Florida); and similar entities in Texas, Louisiana, and Alabama. The Gulf of Mexico Alliance (GOMA), a nonprofit, emphasizes the need for such collaboration with representation from all five Gulf states and an Integrated Planning Cross-Team Initiative that “supports the implementation of adaptation, conservation, and resilience activities at the local community and regional scale” and includes team leads from Louisiana, Texas, and Mississippi.64 By contrast, in the Northeast, New York, New Jersey, and Connecticut coordinate interstate and intrastate planning efforts through the Regional Plan Association (RPA).65 Although the geographic scale of the RPA’s scope is much smaller than that of the Gulf states, both these regions have shared systems, whether economic, environmental, social, or otherwise. RPA informs policy makers and decision makers about economic development and public works through “independent research, planning, advocacy and vigorous public engagement effort”; it also convenes experts to develop long-range plans that shape “land use, transportation, the environment, and economic development.”66 In the Gulf region, similar regional strategies could identify opportunities for receiving communities and address the challenges of originating communities, readying the states and municipalities for more detailed efforts. While regional authorities can play an essential boundary-spanning role, there are myriad challenges associated with community-driven relocation that would require a multi-scalar planning approach spanning regional (i.e., watershed), county, municipal, neighborhood, and site scales in both areas from which people are moving and the ones to which they are moving.