Has the universe ever felt smaller, or less mysterious? We humans can only permanently live on a small fraction of our home planet, but with a few taps on a keyboard or a screen, we can instantly learn much of what there is to know about extreme environments that only belonged to imagination for most of history — places most of us will still never see firsthand. The loneliest expanses of the ocean; the austere, shifting beauty of the Arctic and Antarctic; the almost incomprehensible landscape of Mars, where the volcano Olympus Mons rises over twice as high as Mount Everest and covers an area almost the size of Poland, and the Valles Marineris canyon system stretches for upward of 2,500 miles — longer than the distance from Boston to Seattle.

Learning about these places and experiencing them, however, are two entirely different matters. That’s where composers like Lei Liang and David Ibbett are picking up the thread, weaving scientific data into musical scores to bring us even closer to these no man’s lands than images or words allow.

Liang, who just finished the first of several planned stints as a visiting artist at Boston Conservatory at Berklee College of Music, founded his namesake laboratory at University of California, San Diego on the belief that science and art must be perpetually in conversation.

One of his more recent pieces, “Six Seasons,” asks any number of musicians to improvise along with sounds recorded over the course of a year in the Chukchi Sea, one of the most forbidding locations on Earth. The Mivos Quartet released a recording on New World Records last year, and another recording is forthcoming from solo violinist Marcos Fusi later this year.

With the use of underwater microphones, Liang said over the phone, “we can put our ears 330 meters below the sea surface to listen to the ocean,” and so learn “how water propagates sound, how the warmth of water bends sound in the ocean, echolocation — all these things are really part of our learning now.” The composer excitedly described the sound of sea ice forming as one of the most beautiful he’d heard in his life.

Advertisement

“How do you say ‘the most unpredictable, the most refreshing, and the most fragile,’ all at the same time?” said Liang. “The sound of ice that is not so hard yet. Harder ice starts to make higher pitched, more crispy sounds, whereas the birth of ice sounds flaky. Fragile. If you listen to it, it’s almost like it’s starting to speak.”

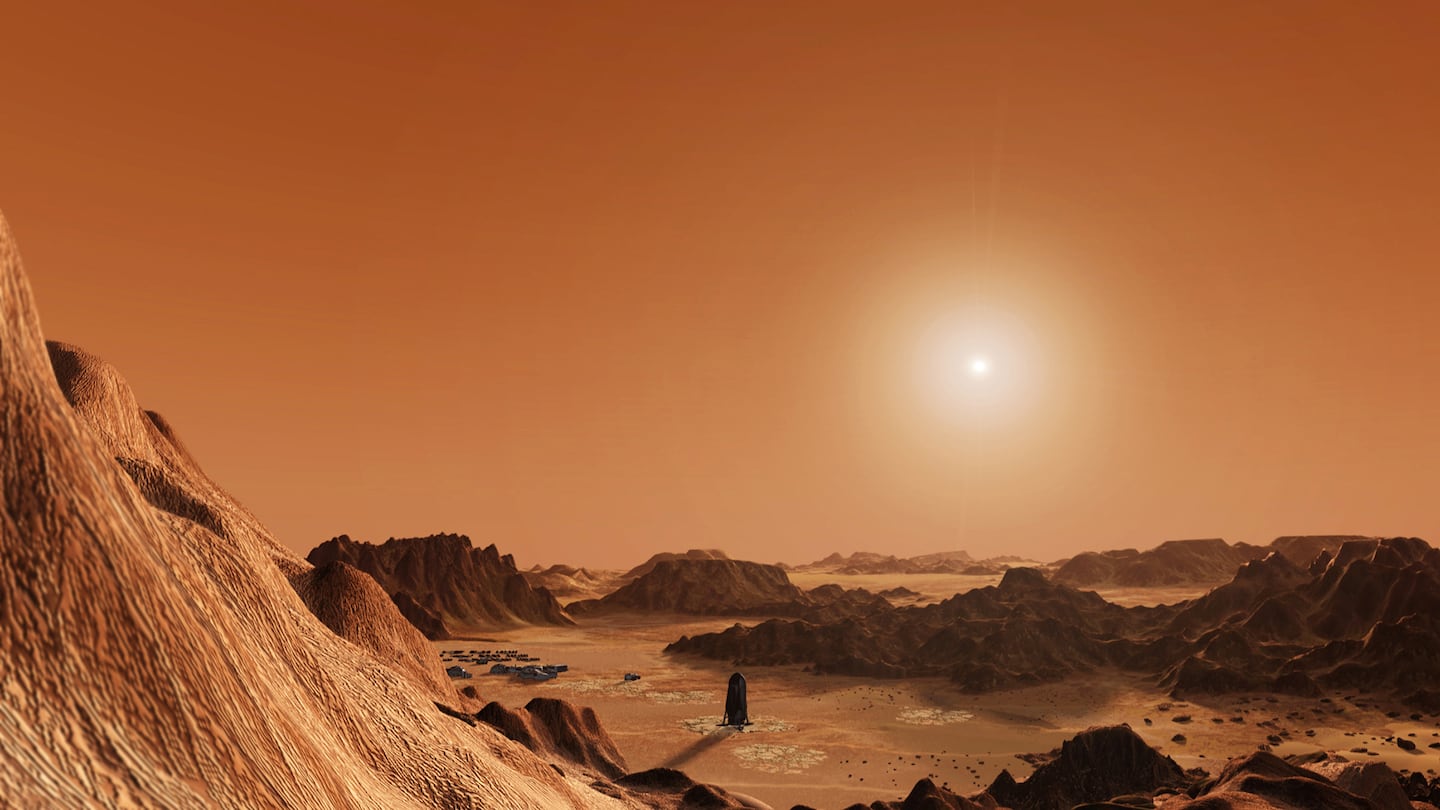

Ibbett, who teaches at Worcester Polytechnic Institute, debuted the full version of his “Mars Symphony” at the Museum of Science late last month, with two more performances to follow still. As alien vistas surrounded the audience and chamber ensemble in the Hayden Planetarium, a desolate howling roared through the speakers; the sound of the Martian wind as captured by the Perseverance rover, which landed on the Red Planet in 2021.

“Mars Symphony,” which was created with the Museum of Science and the NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory, juxtaposed hard data with speculative fiction. Ibbett’s score fused electronic chamber-pop with orchestral conventions, including a reference to the famous 5/4 ostinato of Gustav Holst’s “Mars.” Most memorably, the piece included a touching aria sung from the point of view of a Mars rover by soprano Agnes Coakley Cox, a lonely solo on the electric guitar, and musical translations of altimeter data that mapped the radical elevation changes on the seemingly barren planet.

The planetarium itself isn’t an acoustically friendly space — the sound of the chamber ensemble was often both thin and overwhelmingly loud — but for visual spectacle and wonder, the Hayden Planetariumcq team made something frankly out of this world. Ibbett’s previous project with the Museum of Science gave a similar musical treatment to data from black holes, those terrifying and mysterious cosmic engines from which not even light can escape.

Advertisement

Liang’s collaborator Joshua Jones, of the Scripps Institute of Oceanography, likes to compare the process of artists working with data to a tea ceremony. The data on its own is “a cake of tea leaves,” Liang said, and the artists are the tea masters. On its own, “you can’t taste it, you can’t smell it.” But under the right conditions, “we can experience, as a human experience, what these materials can be.”

“Can be” is the key here. The performance of “Mars Symphony” included a mention of the “universal language of music,” but Liang’s artistic interpretation of the data won’t be to everybody’s tastes, and neither will Ibbett’s.

However, in cases like these, thinking the sounds are pleasant or wanting to hear them again doesn’t feel as important as the fact that we can listen to them at all. They can transport us into parts that may always be terra incognita and, in doing so, they can nurture our curiosity and remind us that the world (and beyond) isn’t so small after all.

MARS SYMPHONY

July 25 and Aug. 29. Museum of Science, Boston. 617-723-2500, www.mos.org

A.Z. Madonna can be reached at [email protected]. Follow her @knitandlisten.