Goodfellows: How Martin Scorsese pursued Powell and Pressburger – and made them his closest friends in film

One was a blazing, brilliant, bearded American moviemaker at the height of his fame, the other, a fogeyish, out-of-fashion British duo, who loved Bach, Scottish mountains and... Arsenal FC. Geoffrey Macnab recalls the film world’s most peculiar – and fascinating – friendship

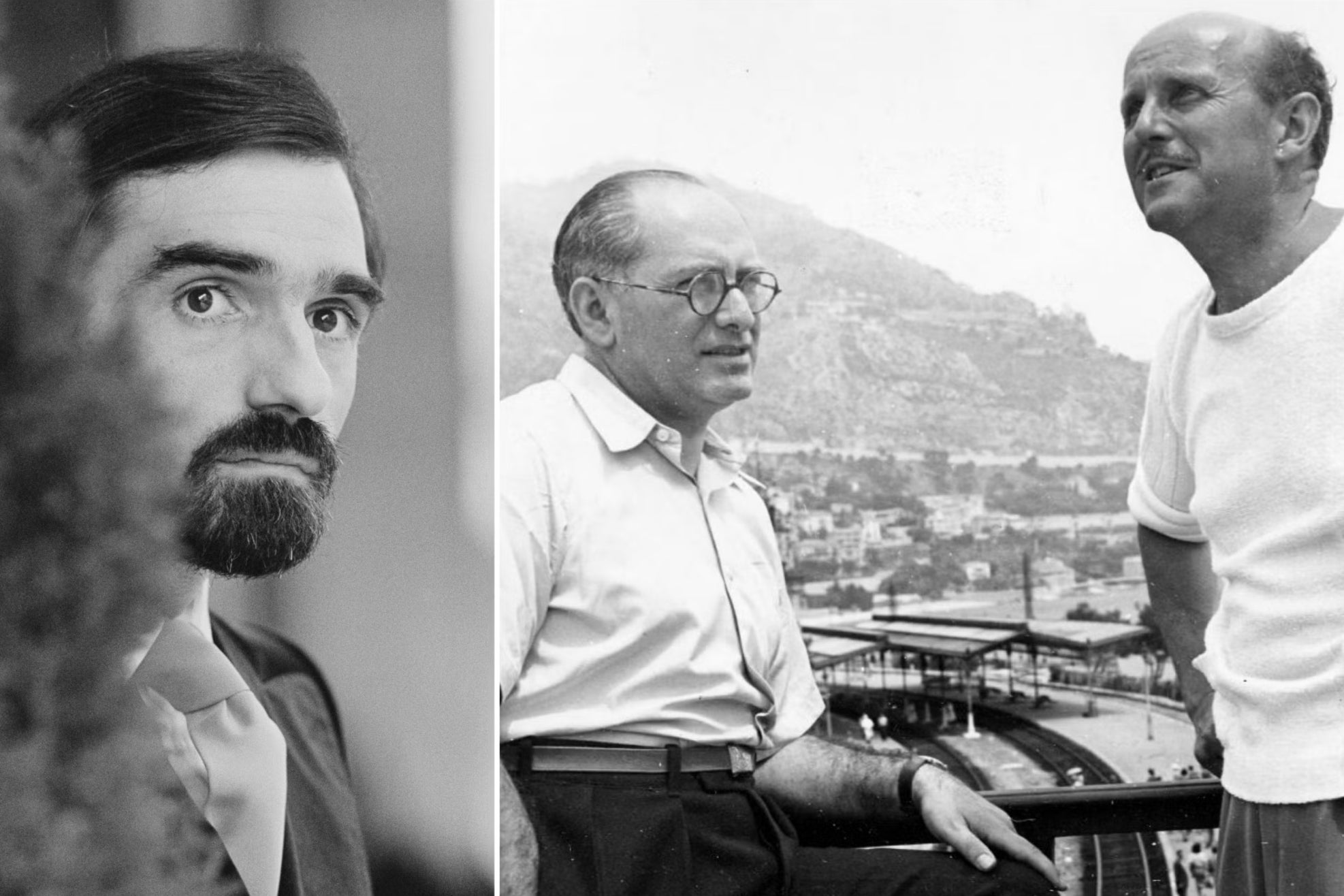

It’s one of the stranger partnerships in cinema history – the fiery, motor-mouthed, New York-based Italian-American filmmaker Martin Scorsese and the patrician English director, Michael Powell. When their friendship began in the mid-1970s, Scorsese was at the height of his powers, while Powell was a near-forgotten figure in the UK film industry whose reputation still hadn’t recovered from the critical drubbing he had taken a decade earlier, for his voyeuristic serial killer movie, Peeping Tom (1960).

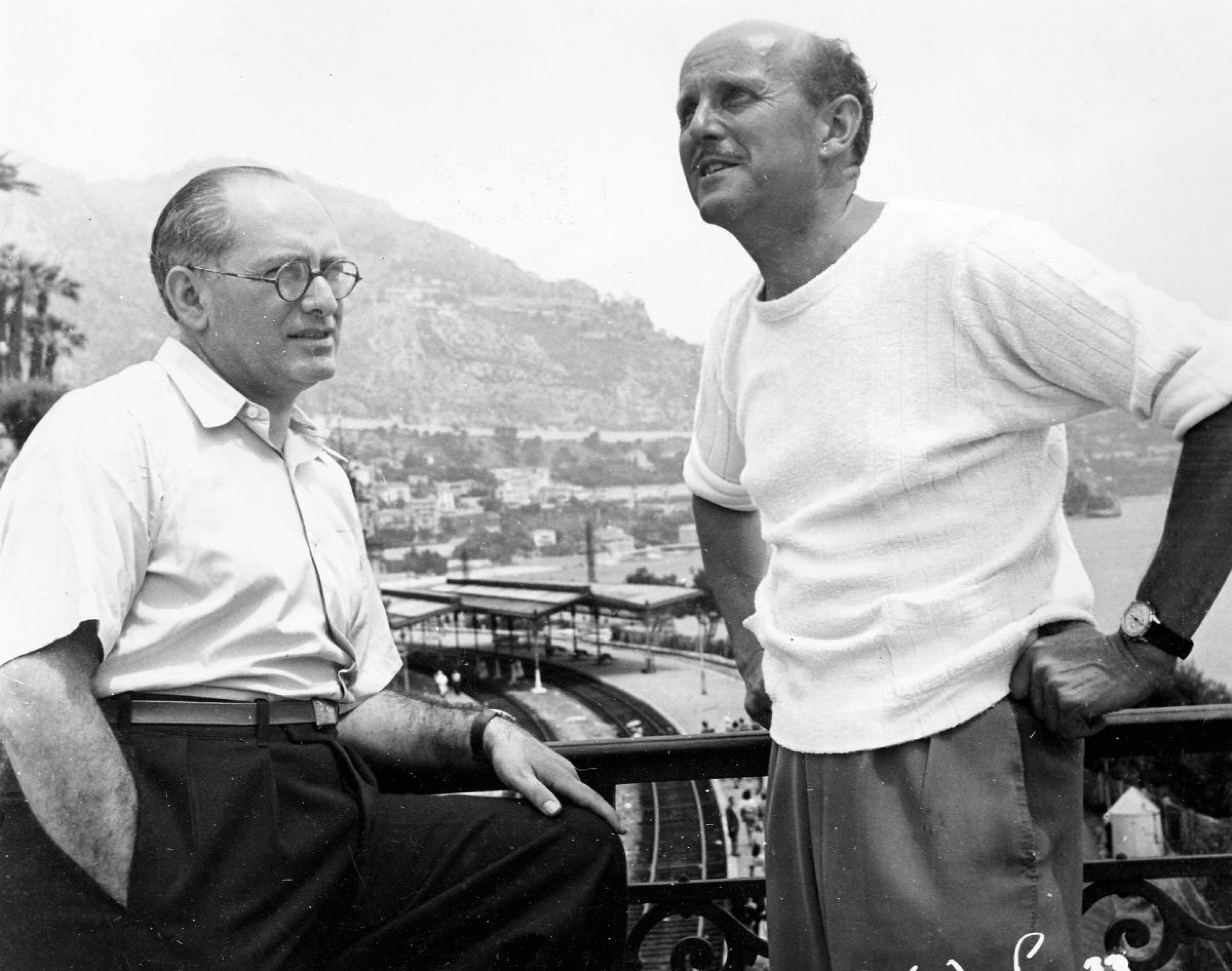

Powell and his partner Emeric Pressburger (whose career together is celebrated next month with a major season at the BFI) had been reduced to making kids’ movies like The Boy Who Turned Yellow (1972) and lowbrow skits like the Australian-produced comedy, They’re a Weird Mob (1966). The glory years of their best known pictures The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp (1943), A Matter of Life And Death (1946), Black Narcissus (1947) and The Red Shoes (1948) were a very long way behind them. Nonetheless, their young American admirer remained convinced that Powell (1905-1990) and Pressburger (1902-1988) were “the most subversive filmmakers ever to be financed by a major studio”.

The man who brokered the introduction between Scorsese and Powell was the publicist, filmmaker and distributor Mike Kaplan, well known for his work with Stanley Kubrick and Robert Altman. As Kaplan told me this week, he had been working as an agent for his friend, the actor Malcolm McDowell, when he first encountered Powell.

Powell was intrigued by the films Kaplan was then distributing – art house movies like David Hockney documentary A Bigger Splash (1973) and Barbet Schroeder’s The Valley (1972), which had music by Pink Floyd – and the two men became friends. The English director would often drop by Kaplan’s offices near Holland Park.

“Marty Scorsese was coming into London and I was friendly with Marty,” Kaplan remembers. “I got a call from him and he said, ‘Do you know Michael Powell?’” He replied that he did indeed know Powell who was actually due in his office later that day. Scorsese made it clear he was desperate to meet him.

“It was uncanny. It was meant to be,” Kaplan says of Scorsese’s meeting with Powell.

The young American had recently completed Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore (1974). Kaplan arranged a screening that Powell attended and then they all went off to have lunch together at Julie’s Restaurant in Notting Hill.

As they sat across the table and enjoyed a glass of wine, the British filmmaker was initially startled by Scorsese’s exuberant enthusiasm for his work. After all, during that period, Powell was living in a trailer. He had very little money and his older films had fallen into neglect. He was struggling to get any new movies off the ground – and here was Scorsese telling him he was one of the greatest filmmakers who had ever lived.

“I do talk rather quickly. I was excited. He seemed rather modest and somewhat taken aback,” Scorsese later recalled in an interview collected in the book, Screen Epiphanies. “I was rather effusive about him and his work. I couldn’t believe we had found him! We brought him up to date about the appreciation of his and Emeric’s work among the younger filmmakers.”

Powell later described Scorsese as looking like a Jesuit priest, “a pale fanatic, eyes that burn, a close-clipped beard”.

It was the beginning of a beautiful friendship that would last until the older man’s death 16 years later; one that would take Powell to the US and would see him marry Thelma Schoonmaker (the renowned editor of Scorsese’s films).

Now, 30 years on, Scorsese is narrating a documentary about Powell and Pressburger. When the film, directed by David Hinton, was announced last year, Scorsese again acknowledged his enduring love of their work.

“I’ve seen the films that he (Powell) made with Emeric over and over again but the experience of excitement and mystery that I get from them doesn’t just remain, it deepens. I don’t know how it happens but for me, their body of work is a wondrous presence, a constant source of energy, and a reminder of what life and art are all about.”

On the face of it, Scorsese’s obsession with Powell and Pressburger is a little baffling. They come from such different worlds. At the time that Scorsese was making his blistering boxing drama Raging Bull (1980), Powell and Pressburger were invited to appear on the BBC radio show Desert Island Discs. As they discussed their lives and career together, the duo sounded a little fogeyish. By then, Powell was living in a cottage in Gloucestershire while the Hungarian-born Pressburger, who had come to England in the 1930s, was based in Suffolk.

As the show’s host Roy Plomley earnestly told listeners, these two Beethoven and Bach-loving veterans of the British film industry were actually behind some “very fine films”.

The two men existed in a world a very long way removed from that of Scorsese. Outside film, they had very different interests. Pressburger had followed Arsenal football club for over 50 years. In the mid-1930s, he and his friend and fellow emigré, German producer Gunter Stappenhorst, used to travel to all the club’s away matches in “Stapi’s big black Chrysler” as the filmmaker’s grandson and biographer Kevin Macdonald later wrote. Macdonald described Arsenal as the “most durable passion” of Pressburger’s life.

Much of Powell’s spare time, meanwhile, was spent hill walking in the Highlands of Scotland. He may have been born in Canterbury but he loved to venture north, taking the sleeper train to Inverness and making sure he had copious supplies of chocolate and whisky in his rucksack.

You can’t quite picture Scorsese clambering up Ben Mor Coigach or standing on the North Bank Terrace at Arsenal. Nonetheless, he revered the two filmmakers and regarded them as inspirational figures.

Scorsese’s obsession with Powell and Pressburger had started very early. He was taken to see The Red Shoes as a kid. Growing up on New York’s Lower East Side, he watched their films on TV. As he later emerged as a filmmaker in his own right, his curiosity about them grew ever more intense.

“We were all wondering who they were, where they were and whether they were still alive,” Scorsese said, remembering how, in the early 1970s, he and fellow US directors like Steven Spielberg and Brian De Palma would talk among themselves about what had become of Powell and Pressburger. They couldn’t find out much about them. They were fascinated and puzzled by the title cards on their movies, which read, “Written, produced and directed by Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger.” They were intrigued by the logo at the start of the movies, “A Production of the Archers”, appearing over a target as an arrow thuds into the bullseye.

Why did Scorsese so revere their work? He suggested recently that their films were “grand, poetic, wise, adventurous, headstrong, enraptured by beauty, deeply romantic, and completely uncompromising”.

What such words don’t reveal is the eeriness and perversity also often found in their work. Take A Canterbury Tale (1944), their hugely evocative wartime drama made in Powell’s home county, Kent. On the one hand, it celebrates the cathedrals, rolling meadows and thatched villages of pastoral England. It invokes the spirit of Chaucer while playfully picking up all the cultural differences between the locals and the American GIs who’ve arrived in their midst. On the other, it unleashes a phantom “glueman”, a mysterious figure who squirts glue on the hair of young women. “Oh my goodness, it’s my hair. Someone came out of nowhere and poured something on it… some sticky stuff,” a woman shrieks early in the film. “This is England, never a dull moment,” an American soldier murmurs sardonically.

Powell and Pressburger’s films often featured obsessive loners not so different from the protagonists in Scorsese’s movies. The glueman Colpepper, a country squire played by Eric Portman who wants to stop English women being seduced by GIs, is every bit as odd in his own very English way as Robert De Niro’s vigilante Travis Bickle was in Taxi Driver (1976).

Lermontov, the ballet impresario in The Red Shoes, is a driven, single-minded figure, ready to sacrifice everything for his art – so an artist with values very like those of like Scorsese himself. Peeping Tom’s serial killer Mark Lewis (Carl Boehm), who tried to photograph his female victims at the very moment of their death, is the type of character you expect to find in a 1970s New York exploitation pic, not a British drama. (Powell made that film with writer Leo Marks, not Pressburger.)

Scorsese had talked of his attraction to the “darker side” of Powell’s vision, “where the art becomes sinister and perverse in a way”. He was struck by the English director’s “audacity” in getting an audience to feel sympathy for a killer. He also relished the way Powell put Peeping Tom together, “the lurid colour… the picture has a nasty edge to it, it brings you close in a funny way to strange, base feelings”.

Then there was their formal ingenuity, for example, the way in A Canterbury Tale they move 600 years forward in time by cutting from a bird of prey in Chaucer’s time to a fighter plane soaring through the sky.

It would be no surprise to discover that certain scenes in his new picture, Killers of the Flower Moon (out in cinemas in October), are directly influenced by the lighting, the framing or the editing in some of Powell and Pressburger’s old films. He has rhapsodised over everything from the mysticism in their island romance I Know Where I am Going (1945) to their use of the colour red.

Next month, the duo’s greatest pictures will be back on cinema screens as part of the BFI’s UK-wide season of their work. We should soon also get to see the new documentary about them narrated by Scorsese. Its title is yet to be formally announced but is listed online as Made in England, and is being talked about as Scorsese’s “love letter” to them.

In the half-century since Scorsese met the English director in that Notting Hill restaurant, he has done more than anyone to dig Powell and Pressburger out of the obscurity into which they had fallen – but their work has fired his creative imagination for even longer than that.

‘Cinema Unbound: The Creative Worlds of Powell and Pressburger’ runs 16 Oct-31 Dec

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments