NIH plan to cheat death by repairing aging brains with youthful cells grown in labs

- READ MORE: Chinese scientists can thaw frozen brain tissue without damage

The US Government is funding 'completely insane' brain transplant research that aims to 'defeat' death.

Geneticist Dr Jean Hébert has been awarded a $110 million NIH grant to develop a surgery that replaces damaged or aging brain cells with tissue from human embryos.

The procedure involves repairing the ailing brain tissue with 'neuronal' stem cells grown in labs, a method which has already shown promising results in mice.

A researcher has proposed a radical idea to cheat death that some scientists are calling 'completely insane

Stem cells are 'blank, shape-shifting' cells that can transform into cells from any other part of the body.

They are abundant in human embryos as a fertilized egg grows and specializes into a complex human being — and their use is at the core of this novel new approach.

'It doesn't require you to understand aging,' Mark Hamalainen, co-founder of the Longevity Biotech Fellowship, said. 'That is why Jean’s work is interesting.'

But others in the field believe the procedure is too severe for common use, and members of the general public have called it 'diabolical.' ('These are the ghouls in charge of "the science,"' as one commenter posted online.)

Dr Hébert's initiative, more formally described as 'functional brain tissue replacement,' showed its first signs of success last year in mice.

The results from that trial prompted this month's government grant to progress into tests on primates before one day moving on to human trials.

Lab mice with brain lesions underwent the procedure, which saw scientists inject mouse stem cells into their aging brains, according to the study published in the journal Bioengineering.

The stem cells were grown through cell culture, which involves isolating cells from an embryo and placing them in a petri dish with nutrients like vitamins, amino acids, glucose and salts.

The team carefully layered a mixture of the lab-grown cells into a protein-based support gel made by Corning, called Matrigel Matrix, which is derived from cell and tissue components that promotes cell growth.

Dr Hébert's preliminary trials in mice showed that these grafted, donor brain cells became 'electrophysiologically active,' firing off and communicating with its mouse host's brain, even responding to 'visual stimuli' within 'one month post-transplant.'

'Using our paradigm, neurons were found to differentiate and project to appropriate targets in the host brain,' Dr Hébert and his team wrote in the study.

The young cells, in other words, matured rapidly into specialized cells that were ready to fulfill their new role in the host brain.

'Moreover, transplant-derived neurons were spontaneously active,' they added, 'integrated [...] into functional networks' within the brain without additional work needed by the surgeons.

These cells were also seen to respond to sensory inputs, based on electrode studies of the mice in later tests.

Dr Hébert's successes caught the attention of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) this year, leading to the multi-million dollar new program.

Modeled off the Pentagon's advanced research wing, DARPA, the new US Advanced Projects Agency for Health (ARPA-H) was created by President Joe Biden in 2022 to play a similar forward-looking role within NIH.

The new brain rejuvenation surgery joins ARPA-H efforts to transplant eyes for the blind, anticipate genetic evolution in cancer cells, and radical new indoor air filters.

Dr Hébert described the project as part of his life's ambition toward immortality.

'I was a weird kid and when I found out that we all fall apart and die, I was like, "Why is everybody okay with this?"' the researcher explained.

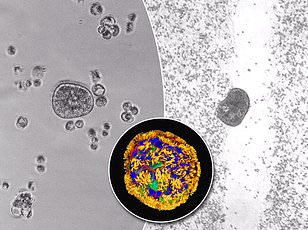

The ARPA-H project will expand geneticist Dr Jean Hébert's tests of his surgical technique from past successful transplants in mice to primates and other animals. Above, microscopic 'immunofluorescence images' show the successful layers of new brain cells in mice

'That has pretty much guided everything I do,' Dr Hébert said. 'I just prefer life over this slow degradation into nonexistence that biology has planned for all of us.'

The geneticist will be leaving his role at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine's neuroscience department in the Bronx for his high-tech ARPA-H post.

The ARPA-H project will expand Dr Hébert's tests of this surgical technique from past successful transplants in mice to other animals including primates, the agency said.

But despite these promising successes, some scientists in the field have expressed doubts about the surgery's practicality or long-term viability.

'On the surface it sounds completely insane,' the CEO of aging research company Oisín Biotechnologies, Matthew Scholz, told MIT Technology Review, 'but I was surprised how good a case he could make for it.'

Scholz, does not expect the surgery to see widespread casual use, however, or spur a new era of human immortality.

'A new brain is not going to be a popular item,' Scholz opined. 'The surgical element of it is going to be very severe, no matter how you slice it.'

Others see the procedure's potential as a possible cure for hereditary cognitive issues.

'If it can work, forget aging,' one medical doctor and biotech entrepreneur, Dr Justin Rebo, said. 'It would be useful for all kinds of neurodegenerative disease.'

Only people with a high IQ can spot the number '6' in this brainteaser in 10 seconds

Only people with a high IQ can spot the number '6' in this brainteaser in 10 seconds