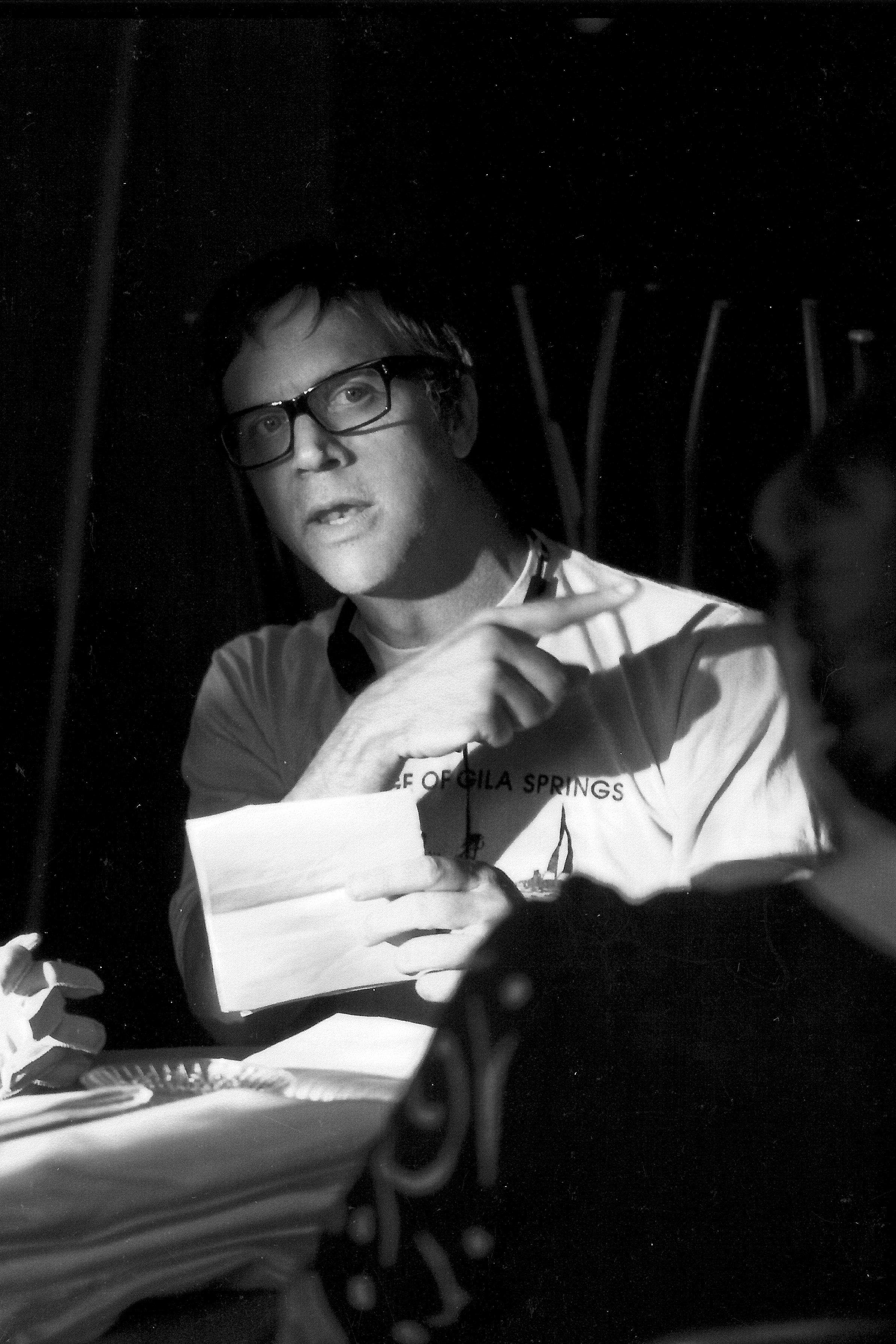

By the age of three, Todd Haynes had already fallen in love. With the atmosphere of the movie theatre, with the awesomeness of the big screen, and above all with her: Mary Poppins. His obsession with constantly re-enacting scenes from the film – with the help of his mother, who agreed to dress up as Julie Andrews – was his first step towards moviemaking. The compulsion grew stronger when, as a nine-year-old, he saw Franco Zeffirelli’s Romeo and Juliet. He would set up a camcorder and have his father play Tybalt (he kept the part of Mercutio for himself), and he even drew the characters on a wall of his home, something his parents were less enthusiastic about. At the recent Zurich Film Festival, he spoke of his forthcoming Freud project and a biopic about Peggy Lee in the pipeline for 2022 (with Michelle Williams in the part of the singer). The 60-year-old Californian filmmaker also retraced the genesis of his latest feature-length documentary, The Velvet Underground, which premiered at Cannes and was released on AppleTV+ on 15 October. Recounting the story of the paradigm-shifting 1960s rock band, the film was in post-production during lockdown, obliging him to hunker down in an editing suite and take solace in his art. His devotion to cinema is only rivalled by his passion for music, a subject he has explored in many previous works, from Velvet Goldmine, a glam rock drama that won an Academy Award nomination for Best Costume Design, to I’m Not There, a biographical film freely based on the life of Bob Dylan. An LGBTQIA+ activist, he has always supported the community with culturally impactful works such as Carol, a love story acted out on screen by Cate Blanchett and Rooney Mara. Social struggles make part of his ancestry, with a grandfather who worked as a union organiser at Warner Bros. during the 1940s. His mother had a degree in art history and his father sang in a college band, providing a childhood environment that nurtured an already natural sensibility for beauty in all its forms. Whenever he writes, directs or produces a film, he prepares a playlist of songs from the period in which the story is set and channels them to get into his characters’ heads. Inspired by the work of German filmmaker Rainer Werner Fassbinder, Haynes makes no attempt to supply the audience with answers. Instead, he seeks to stir up a hornet’s nest of questions to trigger a revolution and bring about a change. Not unlike the Velvet Underground.

In what way did the band’s visual impact influence art, but also fashion?

The ’60s were way ahead in lots of ways. The clothes had a simple, well-defined style that was timeless, and Lou Reed became a legend with his mop of curly hair. Young people back then were obsessed with those bold striped shirts, the band’s leather jackets and even their glasses, which people still wear today, by the way. The Velvet Underground never planned on it, but they were actually the best and most interesting answer to the hippies on the West Coast with all their flowers and colourful looks.

Why did their aesthetic become so influential?

I find it hard to separate the aesthetics from their music. Thanks to Andy Warhol’s Factory, it wasn’t just a sound that they made, it was an all-encompassing experience, hence also visual and avant-garde. They fostered an incredible artistic cross-pollination, breaking down the distinctions between forms of expression, and mixing happenings, music and images.

In the documentary, you draw on Warhol’s technique of splitting the screen into two frames. What was behind that choice?

Warhol used split screen in his movies to link images and sounds, in very powerful aesthetic experiments combining optical effects and geometries. That’s why I recommend watching this documentary at full volume, even if you’re at home, because the sound breaks through the two-dimensional barriers of the image and totally envelops us.

Lou Reed broke so many taboos, including around homosexuality. How do you see this aspect?

His sexual identity influenced his work a lot, not because he was openly gay, but because he took the concept of camp to various levels. He had an intellectual way of inviting people to look at the world differently. There would be all sorts of people at the Factory, from Harvard graduates to people from the street. They shared everything without distinction. That’s why it was a unique counterculture. Many people avoided being seen in public with Andy Warhol, for instance, because he was considered swish. But to him it wasn’t a pose: he came across just the way he was.

Fifty years later, and having conducted lots of interviews and viewed hundreds of hours of footage, what’s your impression of the Velvet Underground?

Even today, the members who are still alive form a dysfunctional family, with John Cale still its heart and soul. He was the one who chose me for the project, and since I’m a huge fan he didn’t have to ask twice. The fact that Lou Reed is no longer physically with us somehow made him feel even more present. He continues to peer out at the viewer from the screen. He has a very strong visual impact because he’s like a reinterpretation of the concept of “elsewhere”.

Did you ever meet him?

Once, in passing at an event, but I didn’t have the nerve to get close and talk. But in the past he was one of the first to let me use one of his songs in the movie Velvet Goldmine. Obviously I was really struck by the fact that he said yes, especially as David Bowie always said no (and incidentally much of his work was a result of the Velvet Underground’s influence). At that moment I was hoping Lou Reed had at least some vague idea of my work, but whether he did or didn’t, it was an unforgettable and exceptional moment for me.

You’re too young to have really experienced the ’60s. How do you see that decade?

When you just catch the tail end of a certain historical period, you always get the feeling you missed out on the right time and place. Looking back, though, I realise I lived through another period without noticing it. In fact, as kids in the ’70s we were fascinated with the pop culture of cinema and music from the past, so we really kept it alive.

What was so special about the cultural creativity of those years?

First of all, there was the physical closeness that fosters art movements, as happened in New Orleans in the late 19th century, Chicago or Paris in the 1920s, and then New York in the 1960s. Instead of being dispersed, the energy is concentrated around people with similar sensibilities. Today we’re almost driven by forces that push us away from each other, first with social media and then with the pandemic, and we tend towards isolation. Online nowadays it’s got to the point where it seems like a sort of rage fest.

How did you manage to complete the documentary in the middle of the pandemic?

We started working on the interviews in 2018. The lockdown was the most alarming period of many people’s lives, and I survived it thanks to this work and the magic that the music gave me.

Were you ever worried you wouldn’t be able to give the music the same impact it had in real life?

The biggest challenge for me was definitely turning the notes into a visual representation, so I also focused on the band members’ sources of inspiration. That’s why the first song in the documentary only comes after over an hour of viewing. In the meantime, you get lost in their world and see all the other artistic elements converging. It’s almost like you only discover the musical element through the back door of the narrative.

How important is the concept of identity in this story?

I’m interested in the idea that identity isn’t clear and definite but elusive, even if society sometimes builds detrimental constructs on it. I don’t like political fundamentalism bound up with the idea of self, whether it’s right or left wing. I prefer moments of rupture, the kind of instability that leads to change. The Velvet Underground had that energy, too, in a pure and enduring form.

Photos “The Velvet Underground”, courtesy of AppleTV+.