Schools

The Progress Report: One City Heights Elementary School Is (Still) Doing The Nearly Impossible

"Every kid deserves high quality education. We don't want to produce cycles of poverty, we want to break the cycle," Lee said.

March 5, 2024

This story has already been written. That’s what makes it even more remarkable. In 2020, former education reporter Will Huntsberry got to thinking about one of the ironclad rules of test scores: they almost always mimic the demographics of the community a school serves. Schools in wealthier areas almost always score better than schools in poorer areas.

Find out what's happening in San Diegowith free, real-time updates from Patch.

Huntsberry wanted to find schools bucking that trend, and he did. Enter Edison Elementary. It’s an unassuming school in City Heights, nestled amid an auto repair shop and a store that specializes in antique coins.

Edison’s test scores are good, but not phenomenal – students perform slightly better than the district wide average in English and well above the district wide average in math. What sets Edison apart is that more than 90 percent of its students qualify for free and reduced-priced meals, a figure more than 30 percentage points higher than the district’s overall average. Twenty-one percent of Edison’s students are homeless.

Find out what's happening in San Diegowith free, real-time updates from Patch.

The school’s high poverty rate and good test scores, however, is why Edison scored the fourth highest of the more than 700 schools countywide on a metric we developed that controls test scores for a school’s poverty level.

Four years later, Edison is now number one. The school’s staying power, and continued improvement, is proof that something very right is going on at Edison.

“I don’t know that there’s a secret sauce,” said Jennifer Oliger, who teaches a fourth grade biliteracy class. She’s taught at Edison for 28 years.

Turns out, Oliger is right. There’s not a secret sauce per se. No single teacher, administrator or bit of curriculum is behind Edison’s longstanding success. It’s more of a secret stew of factors.

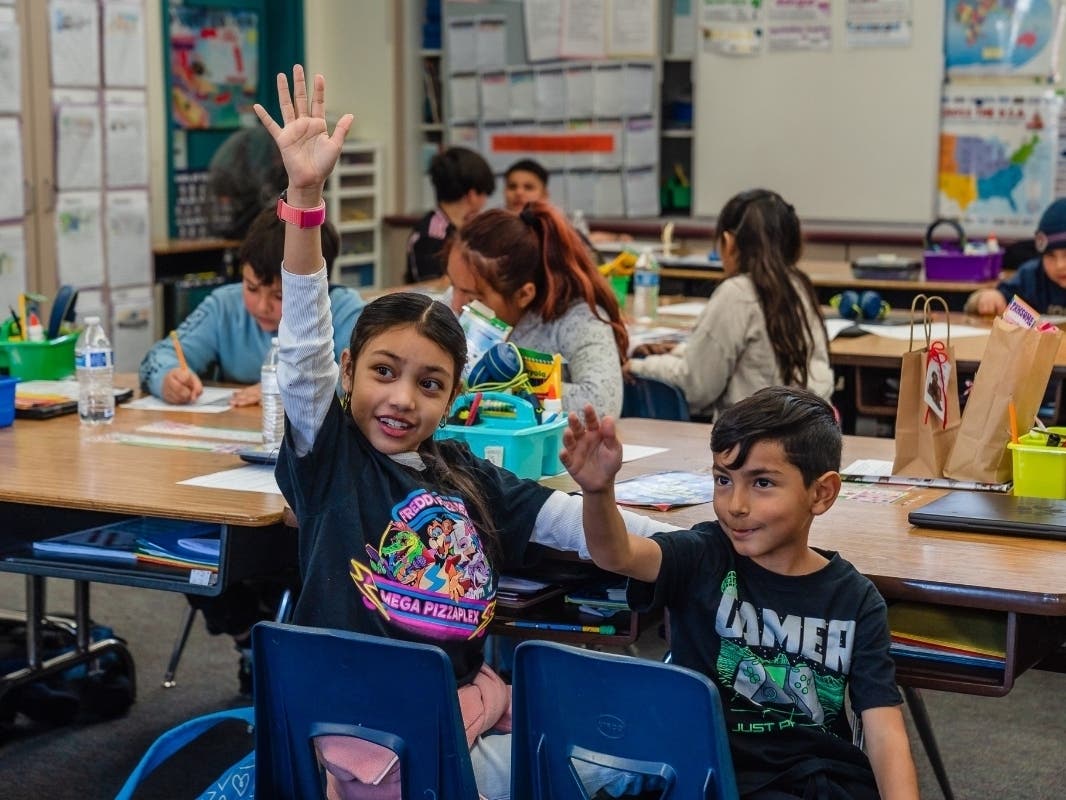

When you step into Edison, there’s no glow or fairy dust. It feels like many other schools. The squat, unassuming main building was built in the ’50s, but it’s complemented by newer two-story buildings and a joint use turf field.

As I stood in the front office, a troop of children marched merrily by, and Principal Jamie Lee greeted each one by name. “Happy Valentine’s Day,” one girl in a pink sweater exclaimed, as she hugged Lee.

Lee, who’s been principal for about four years, has long been focused on equity, so a school like Edison, with all the challenges students faced, was “kind of my dream school,” she said.

“Every kid deserves high quality education. We don’t want to produce cycles of poverty, we want to break the cycle,” Lee said.

Still, when she started, she knew she had big shoes to fill. The school had excelled for years.

“I was a little nervous. I was like, ‘I don’t want to screw up.’ You’ve got to keep the trajectory,” Lee said. But she knew Edison’s teachers were deeply experienced and that she would be able to learn from them.

“This is not at all about me,” Lee said. “Teachers are leading the changes.”

(Left to right) Christina Mortel-Davis and Jennifer Oliger at Edison Elementary School in City Heights on Feb. 15, 2024. / Ariana Drehsler for Voice of San Diego

Teachers at Edison know what they’re doing, because they’ve been doing it for a long time. Most of them have not only been teaching for decades, but they’ve also been teaching at Edison for decades.

That’s remarkable, because it bucks a longstanding pattern. Often, schools in poorer areas tend to be de facto training grounds. New teachers often start in poorer schools and then bolt to wealthier ones. At Edison, the opposite seems true.

The school’s 16 teachers have an average of 21 years of experience, and on average have taught for 17 years at Edison. Nine of 16 have taught at the school for more than 20 years. California recently changed how it reports teacher experience, so it’s unclear how this compares to other schools.

But in any case, that experience is a big deal. Students who have experienced teachers are more likely to not only to do better in school, but also actually show up to school. It also means there are plenty of mentorship opportunities for new Edison teachers.

“New teachers aren’t just going to sink and swim. We’re going to help them along,” said Christina Mortel-Davis, a second-grade teacher who’s taught at Edison for about 24 years.

All this experience also produces another vital asset: trust.

“Some of us have been working together longer than some marriages, so there’s a lot of trust and articulation” quipped Mortel-Davis.

Jennifer Oliger teaches a fourth-grade biliteracy class at Edison. Like Mortel-Davis, she’s also taught at the school for more than two decades. Oliger said that even after students move on to other grades, teachers stay in touch with them.

“We trust what’s happening in other grades, in kindergarten and first grade,” Oliger said. If a student isn’t making progress, Oliger said she feels comfortable going to their former teacher and saying, “how did you teach this or what worked with this student?”

That trust is shared not only between teachers themselves, but also with the community. The teachers have become familiar faces to families. Mortel-Davis said she’s even had the children of her former students as students.

“I’m deeply committed to this school, the kids, the families and the community and the other teachers,” Mortel-Davis said.

That’s why when she moved up to Temecula some years ago, there was no question of whether she would stay at the school. She makes the about hour and a half trek to and from Edison every day.

Collaboration is one of the lynchpins of the school’s success. What Edison’s teachers have developed, Lee said, is a true professional learning community that allows teachers to share strategies, learn from each other and improve year around. They don’t wait until staff meetings, they talk about what’s working before and after school, during lunch and over text, Lee said. They also aren’t afraid to try new things or ditch a strategy that’s no longer delivering results.

“They don’t go ‘I’ve been doing this a long time. I know what I’m doing,’ and just run through the same script. They are constantly adapting,” she said.

That collaboration also extends to counseling. Every teacher I spoke to said school counselor Vanessa Mendez, who has been at Edison for 18 years, plays an outsized role in Edison’s success. She does that, in part, by playing an outsized role more generally.

Mendez advocates for a “comprehensive counseling program,” that allows her to be proactive rather reactive. That means getting into classrooms.

Each year, Mendez develops 30-minute lessons she delivers to students once every two weeks based on needs their teacher has identified. She also works in smaller groups with students who need more guidance.

For Edison, collaboration also extends outside of school. While teachers play a powerful role in preparing kids for whatever’s next, a student’s family is there year after year, long after a child has moved on from a grade or even a school.

Mendez said much of her time is spent trying to ensure kids, and their families, have what they need to succeed. With homelessness on the rise, Mendez tries to coordinate housing for families who may not have a home. This year the school partnered with Feeding San Diego to create an on-campus food pantry that gives students supplies to take home. They’re working on parental nutrition classes and have even offered Zumba classes.

“We know our families and their needs,” Mendez said.

But that collaboration isn’t just about providing basic needs. Mortel-Davis said she frequently coaches parents about how to best help kids at home. After all, you can’t become a good reader if you only pick up a book at school. That’s one key to learning she tries to impart on parents – “it has to extend beyond the campus.”

“This is a team effort. I’m going to do my part, so (parents) have to do their part and do it with consistency,” Mortel-Davis said.

While many of Edison’s virtues can be squishy, the school’s utilization of data is not. Much like her predecessor, color coded printouts adorn one wall of Lee’s office. They show how each student at the elementary school is doing on formative assessments they perform a couple of times a year. That data is a jumping off point for Edison’s teachers.

“We don’t want anything to slide through the cracks … so with every kid who’s falling behind, we’re like, ‘what’s the plan for this? What are we going to do?’” Lee said.

Lee is hands-on. She spends time in classrooms every day, checking in with students who may be falling behind and working to ensure kids’ interests are nurtured – whether that means starting a gardening or chess club based on student inquiries.

Those assessments also shift how Edison approaches its broader schoolwide teaching strategies.

Two years ago, first grade teacher Lizbeth Salas – who’s taught at Edison for 22 years – noticed students weren’t receiving enough phonics instruction, so she went out and found ways to incorporate more robust phonics building blocks into the way she taught kids to read. It’s made a difference, Salas said.

“Over the years, we have gone from being at the bottom of the bottom to making our way up,” Salas said. “The kids are not just a number. We see them as little individuals, and we see their potential, and we push them. Even the kids that are struggling, we try to push them in a way that is supportive, and respectful.”

More recently, they noticed students were struggling with vocabulary, which significantly impacts reading comprehension. So, a teacher found a tool to help. Educators are careful to say that no new tool is a silver bullet, but each new tool does allow them to make changes that can push student performance forward.

“We’re always acting on data and thinking about what new strategies or programs we can bring in that will help meet students where they are,” Oliger said.

Edison’s Spanish and English biliteracy program means teachers have double the languages to impart on students. And teachers are conscious that their students often come from disadvantaged backgrounds, but they’re also aware that their unique backgrounds bring strengths too. Still, teachers expect excellence.

“We don’t look at our kids as coming from poverty. We have super high expectations, not just with academics but with behavior,” said Therese Leclerc, a third-grade teacher who’s also worked at Edison for decades.

When you walk into Leclerc’s class, there’s a low buzz. Students are in groups of two, quietly reading to each other from Scholastic magazines about U.S. politics. It’s calm, orderly. Then, a boy zooms by Leclerc and she stops him to gently, but firmly, remind him that running in class isn’t appropriate.

“I couldn’t teach in chaos, and they couldn’t learn in chaos,” Leclerc said with a slight chuckle.

All of Edison’s teachers agree that Mendez’s work cultivating campuswide culture has been instrumental in fostering good behavior. Sometimes when they get new kids, their old schools warn Edison staff that they have behavior issues.

“Then those kids become immersed in the culture of the school, and those behaviors don’t show up, because everyone around them is behaving kindly,” Mendez said.

“I think we treat the kids with respect and the respect is reciprocated,” she said.

At times, what makes a great school great can feel ineffable, even for teachers at a great school like Edison. Almost every person I spoke to said something to the effect of “I’m sure schools across the district are doing what we’re doing.” And school culture, which many of them point to, is hard to replicate. Whether it’s years of experience, teacher chemistry or trust built with the community, these things take time, dedication and consistency.

San Diego Unified board member Shana Hazan said she’s long been “obsessed,” with Edison, which falls within the subdistrict she represents. From the way the school uses data, to how it enlists parents in the academic experience to how it deploys counseling strategies with intentionality.

There isn’t one thing that makes Edison great, Hazan said, there are a constellation of factors. But she thinks that the school’s approach offers a roadmap to success for other district schools. When it comes to paying attention to what’s working and replicating it, though, Hazan said “we’re not doing that consistently.”

“We have a model here. And that’s the work that I’m pushing for us to do as a district … how do we do what Edison is doing everywhere, recognizing that every neighborhood is different and every community is different. But up against incredible odds, we are seeing students succeeding, thriving and feeling supported,” Hazan said.

Voice of San Diego is a nonprofit news organization supported by our members. We reveal why things are the way they are and expose facts that people in power might not want out there and explain complex local public policy issues so you can be engaged and make good decisions. Sign up for our newsletters at voiceofsandiego.org/newsletters/.