What if Lucy Letby is innocent? Her case must be reopened as growing doubts about her conviction are raised by medical experts and criminologists, argues PETER HITCHENS

- LISTEN: The Trial of Lucy Letby, The Mail’s #1 True Crime series is available wherever you get your podcasts

If Lucy Letby is guilty, then there is a strong case for executing her. Her supposed crimes are so cruel and so grievous, and there are so many of them. It is hard to see any argument against the death penalty — if she is guilty. Death would be far more merciful than keeping her locked up until she dies.

A serial child killer in prison, despised by all, endlessly at the mercy of other prisoners, never safe from sudden assault, must surely be among the most miserable people on earth. But that is if she is guilty. It is much, much worse than that if she is innocent.

If she is not guilty, then she should be freed as soon as humanly possible. Every second she serves is an outrage. This is why I believe the Criminal Cases Review Commission should move to have the case reopened as soon as possible.

While it does so, the prison authorities should be instructed to make strenuous efforts to keep her from harm. The courts, likewise, should start behaving as if it was possible for trials to go wrong.

I am baffled by the Appeal Court's swift rejection of her request for leave to appeal. Are these eminent persons interested in justice, or in procedure? The record of our courts, in putting injustice right — slow and reluctant — is bad enough as it is.

Listen to the #1 True Crime podcast, The Trial of Lucy Letby

-

LISTEN: The heart wrenching words of Baby K's mum at the Letby trial

LISTEN: The heart wrenching words of Baby K's mum at the Letby trial

-

PODCAST: Letby found guilty again, listen to reactions to the verdict

PODCAST: Letby found guilty again, listen to reactions to the verdict

-

Letby Trial: The final words read to the jury before the verdict

Letby Trial: The final words read to the jury before the verdict

-

PODCAST: Letby says she's not 'sort of person that would kill babies'

PODCAST: Letby says she's not 'sort of person that would kill babies'

-

LISTEN: Jury see video of Letby questioned on camera for first time

LISTEN: Jury see video of Letby questioned on camera for first time

Former nurse Lucy Letby, 34, was convicted last year of murdering seven premature babies and trying to kill six others at the hospital where she worked

-

LISTEN: The heart wrenching words of Baby K's mum at the Letby trial

LISTEN: The heart wrenching words of Baby K's mum at the Letby trial

-

PODCAST: Letby found guilty again, listen to reactions to the verdict

PODCAST: Letby found guilty again, listen to reactions to the verdict

-

Letby Trial: The final words read to the jury before the verdict

Letby Trial: The final words read to the jury before the verdict

-

PODCAST: Letby says she's not 'sort of person that would kill babies'

PODCAST: Letby says she's not 'sort of person that would kill babies'

-

LISTEN: Jury see video of Letby questioned on camera for first time

LISTEN: Jury see video of Letby questioned on camera for first time

So much depends on the rightness of this conviction that nobody with a conscience can live through a single day without worrying about it at least once. And there is now so much thoughtful, responsible criticism of the verdict that we all have a duty to consider it.

An explosion of serious, well-researched journalism on both sides of the Atlantic, casting doubt on the verdict, has, in recent days, changed the weather. It is no longer possible to dismiss all doubters as conspiracy theorists.

Even so, why listen to me, of all people? I am no expert on the complexities of air embolisms, insulin or statistics, all crucial in the case.

Well, the jury and the judge were not experts either. Nor were the prosecuting lawyers. But nobody dismisses their actions or decisions on the basis that they were not experts. So it is at least possible that other non-experts can have valid views on the case.

If you dispute what I say here, then consult the growing library of criticism of the verdict from experienced doctors and from skilled users of statistics.

Perhaps above all, you may now read online the long dissection of the case by Rachel Aviv, in The New Yorker. This is based on multiple conversations with experts and an impressively thorough reading of trial transcripts.

And do not accuse me of being a 'do-gooder' who thinks everyone is innocent. I am a hardline supporter of the due punishment of responsible persons. I reject sociological excuses for crime. I want our prisons to be tougher, not softer.

And, if I had more trust in our justice system, I would be a supporter of the death penalty. But this case is one of the reasons I cannot be.

Then there's the suggestion that people take Ms Letby's side because she is young and pretty and does not look guilty. This has been expressed by Dr Dewi Evans, the main expert witness for the prosecution, who recently complained: 'In this case, Letby is a young, white, English nurse from a reputable, normal background. So it's not surprising that some people respond to the fact that she has been found guilty of killing babies by saying it hasn't happened.'

Well, no doubt her appearance does influence people. I expect it influenced me. But that does not mean the case against her is sound, or that I — or others — will only ever take up the causes of attractive people.

I have been involved in two campaigns against injustice. One is for the lawlessly sanctioned pro-Russian blogger Graham Phillips, who is pretty unappealing. The other was to defend the reputation of Bishop George Bell (not Ball), who is very dead, and has indeed been dead since 1958.

In neither instance was I influenced by their far from pretty faces. And when I first wrote in defence of Ms Letby, in September last year, public opinion was pretty heavily against her. What I didn't like about the case — and still don't like — was the vagueness of the evidence and the way she was never in fact presumed to be innocent in practice.

Nobody ever saw Lucy Letby harm a baby. Nobody has ever come up with a reason why she should have done. Keeping case notes is not evidence of murder. Nor are Facebook searches.

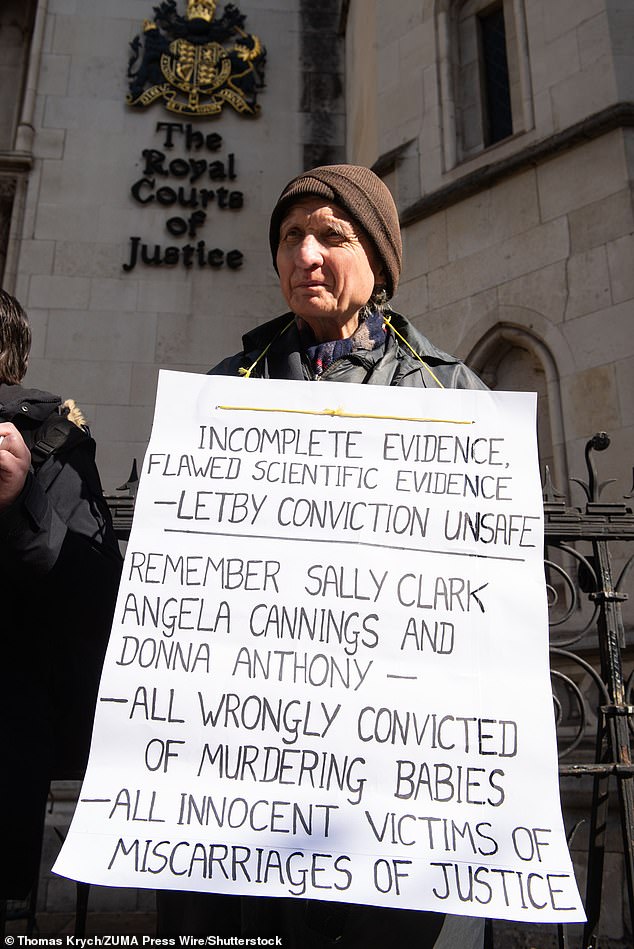

Supporters of Letby demonstrate outside the High Court in London during her appeal hearing

Campaigners claim that Letby is in fact a victim of a miscarriage of justice

Ms Letby liked doing Facebook searches, and had made more than 2,000 of them in the year of the deaths she is accused of causing. She searched for colleagues, dancers in her salsa classes, people she had randomly met.

Claims that she was caught 'virtually red-handed' are worthless. She was not caught red-handed at all. My (Oxford) dictionary defines the word 'virtually' as 'to all intents and purposes; as good as; practically'.

It defines 'red-handed' as 'in the very act of committing a crime'. That is exactly what never happened. The allegedly 'red-handed' event is only evidence of Lucy Letby's guilt if you have already decided she is guilty.

What actually happened in the Countess of Chester Hospital in those distressing months? Most of the babies Lucy Letby is accused of murdering were examined after death by pathologists. They, unlike the prosecution's expert witnesses, actually saw those babies.

Crucially, they either found natural causes or suggested the possibility of accidents. They did not find evidence of murder.

The methods Lucy Letby is accused of using to kill the babies are extraordinarily complex, and strangely varied. Much of the evidence of air embolism (death from injection of air into the bloodstream) was based on skin discoloration. This has now been greatly undermined by the Canadian Dr Shoo Lee, one of the leading experts on the subject.

As with so many other things in this trial, actual evidence is hard to find. And where it can be found, it is often puzzling and open to debate.

Some doctors are baffled by the theories advanced by Dr Evans, the main prosecution expert witness, and have gone on record to say so since it became possible to discuss the case in public.

How did he settle on air embolism as the main means of murder? He had not himself seen a death by air embolism in his long years of practice, which is not surprising, as they are very rare.

Why then would a killer choose this as a means to kill? It would surely draw attention to the death.

As for the insulin method, which Ms Letby is also supposed to have used, and which was crucial to her conviction, there are so many flaws in it that I must urge you to read Rachel Aviv's long dissection of it in The New Yorker, which has been sporadically available online in this country.

This concludes: 'To connect Letby to the insulin, one would have to believe that she had managed to inject insulin into a bag that a different nurse had randomly chosen from the unit's refrigerator.'

I also don't like the way British justice has in recent years become more emotional and less calm.

In too many cases, prosecutors dwell on the horror of the crime, perhaps because they do not have all that much evidence that the accused person did it.

And I don't like the way in which the vital presumption of innocence seems to have leaked away out of police procedure and out of the courtroom.

Yes, it officially exists. Judges and barristers remind juries of it. But the Letby case looked to me like the whole power of police and courts settling on one explanation of some tragic events, and bulldozing aside any objections to it.

I also don't like the way British justice has in recent years become more emotional and less calm, writes Peter Hitchens

The power of group-think in our society is enormous. Once you have decided that Lucy Letby is guilty, then her strange, tortured note in which she appears to admit to the crimes looks like a confession.

But if you have not decided she is guilty, it could equally well be the midnight scribbling of a distraught, frightened young woman finding herself caught amid terrible accusations, with no obvious way out.

The true presumption of innocence does not allow you to conclude her guilt from those notes. For me, her readiness to undergo severe cross-examination for days on end (which guilty people very seldom do) points equally strongly in the other direction.

Then there are the grieving parents of the babies who died, or nearly died.

Who cannot sympathise with them? Any parent who has held a newborn baby in his or her arms, and especially those whose babies have been born ill or premature, must be outraged that anyone should seek to destroy such a child.

It is even worse if the killer is posing as a friend and wearing the reassuring uniform of a nurse. But their grief and anger are not evidence that Lucy Letby did the things she is accused of.

What is also clear from the accounts now emerging is that the Countess of Chester Hospital was not a happy, harmonious or very well-run place.

The Letby affair began with a nasty confrontation between some of the doctors and Ms Letby, during which she was sidelined into a dead-end job.

When she fought back and sought reinstatement, so that she could once again do the work she claimed to love, this bitter little dispute caught fire, and the police became involved.

The hospital's problems were not confined to the neo-natal unit. It was, like much of the NHS, overworked, understaffed, not perhaps as clean or modern as it might have been.

An outside investigation team found that nursing and medical staffing levels were inadequate. Rachel Aviv records: 'They also noted that the increased mortality rate in 2015 was not restricted to the neonatal unit. Stillbirths on the maternity ward were elevated, too'.

The fact that deaths on the neonatal unit fell after Lucy Letby was removed — often mentioned as damning by those who are sure of her guilt — is easily explained.

The unit had also stopped treating high-risk babies, so it is no surprise that the death rate dropped. And here is another point. The babies in the Chester unit were highly vulnerable in the first place. They were not there because they were perfectly healthy. No serial killer was needed to produce such a death rate.

As The New Yorker stresses: 'In the past ten years, the UK has had four highly publicised maternity scandals, in which failures of care and supervision led to a large number of newborn deaths'.

It cites a report on East Kent Hospitals which said: 'So much hangs on what happens in the minority of cases where things start to go wrong, because problems can very rapidly escalate to a devastatingly bad outcome.'

Finally, there is the apparently damning evidence of Lucy Letby's shift pattern. This is supposed to show that she was unerringly present when all the deaths took place.

But it turns out that the chart excludes deaths and collapses which happened at the unit either when Ms Letby was not there, or when there was little evidence to suggest she was responsible for them.

David Wilson, Emeritus Professor of Criminology at Birmingham City University, says: 'There were other incidents during that time period when Letby wasn't on duty, and in fact there were (at least) nine other neonatal deaths on the ward during that period'.

If these events were included in the chart, it would look very different and far less conclusive.

These problems had been foreseen. In September 2022, shortly before the Letby trial, the Royal Statistical Society (RSS) produced a paper, 'Healthcare Serial Killer or Coincidence?'

In one key passage, it warned: 'While unexpected clusters of deaths, or other adverse outcomes, may raise legitimate suspicions and warrant further investigation, they generally should not be taken as definitive evidence of misconduct.'

The RSS was alarmed by a very similar case in the Netherlands, in which a paediatric nurse, Lucia de Berk, was wrongly convicted of seven murders and three attempted murders in 2004.

This was partly on the basis of statistical errors. But the advice they offered seems not to have been taken during the Lucy Letby trial.

It would be easy to speculate on why so many decent people, all at once, agreed on the rightness of a case which now seems full of holes and riddled with misunderstanding.

It would be easy to attack individuals. I am not interested in that. We all make mistakes, and always will.

My only purpose is justice. And if we are to have a proper justice system in this country it can only survive if the innocent are safe from it, and the guilty are afraid of it.

To ensure that, we must be sure beyond reasonable doubt, before we send anybody down the grim stairs which lead to prison.

PICTURED: Missionary mom-of-two, Virginia Vinton, 57, who killed herself in O'Hare airport baggage conveyor belt as chilling new details of gruesome scene are revealed

PICTURED: Missionary mom-of-two, Virginia Vinton, 57, who killed herself in O'Hare airport baggage conveyor belt as chilling new details of gruesome scene are revealed